Simplified cost options in practice - European Parliament

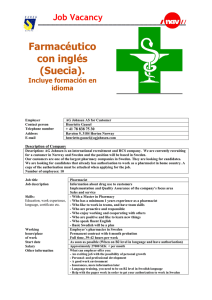

Anuncio