Pharmacological Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis Does

Anuncio

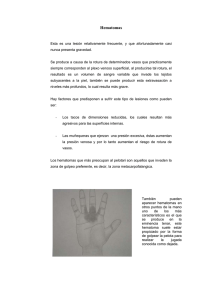

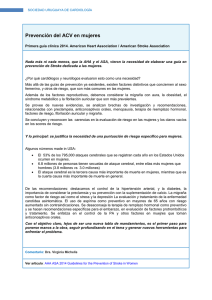

Pharmacological Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis Does Not Lead to Hematoma Expansion in Intracerebral Hemorrhage With Intraventricular Extension Tzu-Ching Wu, MD; Mallik Kasam, PhD; Nusrat Harun, MS; Hen Hallevi, MD; Hesna Bektas, MD; Indrani Acosta, MD; Vivek Misra, MD; Andrew D. Barreto, MD; Nicole R. Gonzales, MD; George A. Lopez, MD; James C. Grotta, MD; Sean I. Savitz, MD Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Background and Purpose—Patients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) are at high risk for development of deep venous thrombosis. Current guidelines state that low-dose subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin or unfractionated heparin may be considered at 3 to 4 days from onset. However, insufficient data exist on hematoma volume in patients with ICH before and after pharmacological deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, leaving physicians with uncertainty regarding the safety of this practice. Methods—We identified patients from our stroke registry (June 2003 to December 2007) who presented with ICH only or ICH⫹intraventricular hemorrhage and received either low molecular weight heparin subcutaneously or unfractionated heparin within 7 days of admission and had a repeat CT scan performed within 4 days of starting deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis. We calculated the change in hematoma volume from the admission and posttreatment CTs. Hematoma volume was calculated using the ABC/2 method and intraventricular hemorrhage volumes were calculated using a published method of hand drawn regions of interest. Results—We identified 73 patients with a mean age of 63 years and median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score 11.5. The mean baseline total hematoma volume was 25.8 mL⫾23.2 mL. There was an absolute change in hematoma volume from pre- and posttreatment CT of ⫺4.3 mL⫾11.0 mL. Two patients developed hematoma growth. Repeat analysis of patients given pharmacological deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis within 2 or 4 days after ICH found no increase in hematoma size. Conclusions—Pharmacological deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis given subcutaneously in patients with ICH and/or intraventricular hemorrhage in the subacute period is generally not associated with hematoma growth. (Stroke. 2011;42:705-709.) Key Words: anticoagulants 䡲 DVT prophylaxis 䡲 intracerebral hemorrhage P atients with intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or ischemic stroke are at high risk for development of venous thromboembolism (VTE).1 In comparison to patients with ischemic stroke, the risk for VTE is higher in the hemorrhagic stroke population.2 VTE risk is also enhanced by immobilization and paresis of the lower extremities and late recognition of subclinical thrombotic events. Without preventative measures, 53% and 16% of immobilized patients develop deep venous thrombosis (DVT) or pulmonary embolism (PE), respectively, in this population.3 One study detected DVT in 40% of patients with ICH within 2 weeks and 1.9% of those patients had a PE.4 Development of VTE in the patient with ICH adds further detrimental complications to an already lethal disease with a 1-month case-fatality rate of 35% to 52%.5 DVT also prolongs the length of hospital stays, delays rehabilitation programs, and introduces a potential risk for PE.6 Current American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines for acute ischemic stroke recommend the administration of subcutaneous (SQ) anticoagulants such as unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) to prevent DVT in immobilized patients.1 On the other hand, American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines for hemorrhagic stroke are less clear stating that subcutaneous anticoagulants may be considered at 3 to 4 days from onset after documentation of cessation of bleeding.5 This tepid recommendation stems from the fact that there is a lack of large randomized controlled trials addressing VTE prevention in the ICH population and even less data are available for patients with intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH). As a consequence, there is no consensus on how and when to start DVT prophylaxis to prevent VTE complications in the ICH and/or IVH population. Continuing medical education (CME) credit is available for this article. Go to http://cme.ahajournals.org to take the quiz. Received August 20, 2010; accepted October 1, 2010. From the Department of Neurology, University of Texas–Houston Medical School, Houston, TX. Correspondence to Sean I. Savitz, MD, Department of Neurology, The University of Texas–Houston Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street Suite, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail [email protected] © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600593 705 706 Stroke March 2011 Figure 1. Study design and population. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Much hesitation arises from the concern that anticoagulants may increase hematoma size and cause neurological worsening.7 There have been 2 small prospective randomized trials published on early heparin use in ICH both showing no increased risk of bleeding.8,9 One recent published prospective randomized trial compared early use of LMWH and compression stockings in patients with ICH also found no increase risk of hematoma enlargement in both groups.6 However, the number of patients was small in these studies and subsequent CTs were not always routinely performed to document rebleeding. With the lack of data and concerns about hematoma expansion, physicians are left with uncertainty regarding the safety of this practice.10,11 This retrospective study aimed to assess the safety of SQ anticoagulants in the ICH and/or IVH population and its association with hematoma growth. Methods Study Design and Population A retrospective search from our prospectively gathered stroke registry from June 2003 to December 2007 identified all patients with the diagnosis of ICH. Patients were excluded who had an ICH etiology of mass lesion, arteriovenous malformation, aneurysm, or undetermined. Hypertensive ICH was diagnosed if patients had a history of hypertension with typical hemorrhage location on imaging. Amyloid bleeds were diagnosed using clinical information, including history of hypertension, blood pressure on presentation and throughout the hospitalization stay, and supportive imaging. Coagulopathy-associated bleeds were diagnosed if patients had ICH in the setting of elevated international normalized ratios on admission. Patients were categorized as having an undetermined etiology if it was unclear whether the etiology was hypertension, amyloid, or both based on the clinical and radiological data. Patients were included after chart reviews confirmed ICH and/or IVH on admission and received either LMWH SQ or UFH SQ within 7 days of admission and had a subsequent CT scan performed within 4 days of starting DVT prophylaxis. Treatment within 7 days of admission was chosen because the guidelines for DVT prophylaxis initiation is unclear and to also capture prescribing trends at our institution. CT scans within 4 days of starting DVT prophylaxis was chosen to allow for variability in posttreatment scanning because this is a retrospective analysis. Separate analysis was performed on patients that received either LMWH SQ or UFH SQ within 2 and 4 days of admission and by diagnosis (ICH only, ICH⫹VH). Chart review was performed on patients who fit the study criteria (Figure 1) to gather baseline demographics and clinical information including admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score and discharge modified Rankin score. Management Patients with ICH and/or IVH were treated according to American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines5 and were not treated with Factor VII or received intraventricular tissue plasminogen activator; however, blood pressures in the acute postbleed period were not strictly protocolized. In patients who demonstrated obstructive hydrocephalus, an external ventricular drain was placed. Two forms of SQ anticoagulants (LMWH⫽40 mg enoxaparin or 5000 U dalteparin SQ once daily, UFH⫽5000 U heparin SQ 2 to 3 times a day) were used at our institution during this period. Medication preference and timing of administration were left up to the discretion of the attending physician. Intermittent compression devices were used on all patients. Radiological All CT scans were performed using identical technique (slice thickness, 5 mm; gantry tilt, 16). Admission CT scans was reviewed by the authors to confirm ICH and/or IVH. All hematoma volume calculations were performed by a single author blinded to the treatment and outcome of the study. ICH volume within the parenchyma was calculated using the ABC/2 method.12 IVH volume was calculated using a published method of hand-drawn regions of interest around each area of intraventricular blood in every slice, multiplied by the slice thickness, and added together to obtain the total IVH volume.13 The sum of the ICH volume and IVH volume was considered the total hematoma volume (HV). The change in HV (⌬vol) was defined as the difference between the total HV of the first posttreatment CT scan and the total HV of the admission CT scan. Hematoma site was classified into deep (thalamus, putamen, caudate), lobar, and other (primary IVH, cerebellar, brain stem). Hematoma Growth We chose absolute hematoma growth as our primary outcome and significant hematoma growth as our secondary outcome. Significant hematoma growth was defined as change in HV ⬎33% and an absolute change in volume ⱖ5 mL. We chose a change in volume of ⬎33% because it corresponds to a 10% increase in diameter in a sphere and it had been used in prior hematoma growth studies.14 An absolute ⌬vol of 5 mL was chosen as the cutoff because the authors felt that a ⌬vol ⱕ5 mL was unlikely to cause clinical deterioration Wu et al DVT Prophylaxis Does Not Increase ICH Volume 707 Table 1. Clinical and Radiological Characteristics of Patients Receiving Pharmacological DVT Prophylaxis Within 7 Days of Admission Baseline Characteristics Total Patients (n⫽73) Mean age, years (range) Patients Without EVD (n⫽52) 63 (37–93) Sex, males/females Median admission NIHSS (range) 63 (37– 87) 40/33 29/23 11.5 (0–40) 10 (0–40) Median discharge mRS (range) 4 (0–6) EVD, % 0 0 0 DVT or PE, % Radiological Characteristics 4 (0–6) 21 (29%) Total HV ICH Only HV Total HV Mean admittance HV, mL (range) 25.8⫾23.2 (0.6–90) 17.6⫾19.3 (0–90) Mean posttreatment HV, mL (range) 21.6⫾22.6 (0.5–108) 17.3⫾20.4 (0–108) Mean ⌬ in HV, mL (range) ⫺4.3⫾11.0 (⫺41.9–23.5) ⫺0.3⫾8.8 (⫺35–38) (P⫽0.0015) (P⫽0.77) 19.5⫾20.3 (0.6–90) 18⫾18.9 (0.7–80) ⫺1.5⫾6.8 (⫺35.0–19.2) (P⫽0.69) Location Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Deep, % 47 (64%) 31 (60%) Lobar, % 14 (20%) 12 (23%) Other,* % 12 (16%) 9 (17%) DVT prophylaxis Enoxaparin, % 50 (69%) 37 (71%) Heparin, % 20 (27%) 12 (23%) 3 (4%) 3 (6%) Dalteparin, % *Other indicates cerebellar, brainstem, primary IVH. NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; EVD, external ventricular drain. and it also accounts for imprecise hematoma volume calculation using CT. Statistical Analysis Using the cutoff of 5 mL and the SD of our data (25 mL), sample size/power calculations were performed and it showed that with a correlation of 0.85, it would require 61 patients for 80% power in detecting a ⌬vol of 5 mL. Means with SDs or medians for continuous variables were used. The differences were assessed using t tests, 2 tests, Fisher exact test, or Mann-Whitney U test. A significance level of 0.05 was used to assess statistical difference. The statistical analysis was performed using SAS 9. Results We identified 73 patients who met study criteria. Baseline clinical and radiological characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 63 years and the median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score on admission was 11.5. Fifty patients (69%) received enoxaparin, 20 patients (27%) received UFH, and 3 patients (4%) received dalteparin. The time from ICH admission to DVT prophylaxis administration also varied; the majority of DVT prophylaxis was administered between Days 2 and 5 (Figure 2). Overall, there was an absolute ⌬vol from pre- and posttreatment CT of ⫺4.3 mL⫾11.0 mL (P⫽0.0015). Analyzing only the ICH portion of the hematoma in all 73 patients showed absolute ⌬vol of ⫺0.3 mL⫾8.8 mL (P⫽0.77). In patients without external ventricular drain placement, the absolute ⌬vol was ⫺1.5 mL⫾6.8 mL (P⫽0.69). Two patients (2.7%) showed significant hematoma growth within the study period. One patient received LMWH and 1 received UFH with hypertension as the etiology of the bleed in both patients. No pattern was identified in regard to clinical and radiological characteristics for these 2 patients who had significant hematoma growth. We analyzed separately patients who received DVT prophylaxis within 4 days of admission and results revealed an absolute ⌬vol from pre- and posttreatment CT of ⫺1.3 mL⫾8.9 mL (P⫽0.31; Table 2). For patients who received DVT prophylaxis within 2 days of admission, data showed an absolute ⌬vol from pre- and posttreatment CT of ⫺0.65 mL⫾5.2 mL (P⫽0.54; Table 2). Discussion To our knowledge, this study is the first to report hematoma growth with regard to the use of SQ anticoagulants for DVT prevention in the ICH and IVH population. In the study recently published by Orken et al, they studied the safety of Figure 2. Distribution of the start date for initiating pharmacological DVT prophylaxis. 708 Stroke March 2011 Table 2. Clinical and Radiological Characteristics of Patients Receiving Pharmacological DVT Prophylaxis Within 4 and 2 Days of Admission Baseline Characteristics Within 4 Days (n⫽50) Within 2 Days (n⫽24) Mean age, years (range) 62.78 (37–93) 63.91 (40 –93) 28/22 10/14 Sex, males/females Median admission NIHSS (range) 9 (0–40) 8.5 (1–40) Median discharge mRS (range) 4.5 (0–6) 5 (1–6) EVD, % 10 (20%) 3 (12.5%) Radiological Characteristics Total HV Total HV Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Mean initial CT volume, 21.6⫾22.7 (0.60–85.5) mL (range) 20.1⫾18.9 (0.6–75) Mean final CT volume, mL (range) 20.3⫾24.4 (0.5–109) 19.5⫾19.7 (0.7–69) Mean ⌬ in CT volume, mL (range) ⫺1.3⫾8.9 (⫺30.7–23.5) ⫺0.65⫾5.2 (⫺18.5–12.9) (P⫽0.31) (P⫽0.54) Location Deep, % 30 (60%) 14 (58%) Lobar, % 11 (22%) 8 (33) Other,* % 9 (18%) 2 (8%) Enoxaparin, % 37 (74%) 19 (79%) Heparin, % 12 (24%) 5 (21%) 1 (2%) 0 (0%) DVT prophylaxis Dalteparin, % *Other indicates cerebellar, brainstem, primary IVH. NIHSS indicates National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, modified Rankin Scale. LMWH and compression stockings for DVT prophylaxis and its effects on hematoma enlargement in patients with ICH. They found that treatment with LMWH (n⫽39) and compression stockings (n⫽36) for DVT/PE prevention was not associated with hematoma enlargement, but did not report the frequency of IVH in their study population nor did they comment on time to medication administration, only that it was given after 48 hours.6 In comparison, the majority of our patients were started on anticoagulants within 2 to 5 days of their hemorrhage with 28% (n⫽20) patients receiving anticoagulants within 48 hours of admission. In general, we found that the administration of pharmacological DVT prophylaxis SQ in the acute (2 to 4 days) to subacute period (ⱕ7 days) was not associated with hematoma growth. Our patients in this study had variable sizes of hematoma from 0.5 mL to 90 mL. In the subacute period, however, 2 patients did develop significant hematoma expansion, but no pattern or factors could be found that were associated with hematoma growth. Hematoma growth was also not observed when the patient population was partitioned by diagnosis (ICH only and ICH⫹IVH) and by the presence of an external ventricular drain. However, the difference in ⌬vol in the ICH only group was much smaller than the ICH⫹IVH group confirming that IVH plays a role in hematoma resolution. Of the 36 patients with ICH⫹IVH, 21 of them had an external ventricular drain placed and we only identified 1 patient who developed bleeding around the catheter. Therefore, starting SQ anticoagulants in patients with external ventricular drains may be safe with low rates of complications. Our data, however, do indicate that patients who were treated in the acute period had lower median admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores (9 within Day 4, 8.5 within Day 2) compared with a median National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score of 11.5 for those treated within Day 7 of admission. This may indicate that there is a tendency to delay SQ anticoagulation in the sicker patients with ICH or possibly those patients with higher admission National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale scores tend to have early rebleeding leading to later SQ anticoagulation administration. Current guidelines for ICH management recommend intermittent pneumatic compression for prevention of VTE, and its use has been demonstrated to be effective.15 Although no randomized data exist, the addition of SQ anticoagulants to intermittent pneumatic compression devices should provide added protection against the development VTE. The widespread availability, low cost, and proven efficacy of SQ anticoagulants for VTE prevention can potentially reduce VTE complications in the highly vulnerable ICH/IVH population. Our study adds to the existing limited literature and further supports the safety of anticoagulants in the acute and subacute period after ICH. Our study is limited, however, by its retrospective nature, small sample size, and the inherent inaccuracy of measuring hematoma volume on CT scan. With the small sample, we were also unable to assess the efficacy of SQ LMWH or SQ UFH in preventing DVT or PE; however, there were no PEs or DVTs observed in the study population. The observed overall hematoma reduction may be largely contributed by ventriculostomy drainage and/or natural hematoma regression; however, when looking at the ICH portion of all 73 study patients, hematoma growth was not observed. Another major confounder may be blood pressure control, because some have postulated that hematoma growth is associated with the degree of hypertension control in patients with ICH.16 The inclusion criteria of the study may have also affected our data and results. First, we only included patients who received DVT prophylaxis. This selection bias may have excluded patients who had more severe hemorrhages with the potential for early hematoma growth in which the attending physician may have chosen to withhold anticoagulants. Conversely, by only including patients who had follow-up imaging, we may also have neglected a population of stable patients who received SQ anticoagulants and were clinically stable, hence not necessitating follow-up CT scans. This may have overrepresented patients with hematoma enlargements in this study because those who clinically deteriorate are more likely to have follow-up imaging. Lastly, by choosing to only analyze the hematoma volume of the first posttreatment CT scan, we were limited in our ability to detect delayed hematoma expansion. In conclusion, data from this study suggest that administration of SQ LMWH or UFH in patients with ICH and/or IVH for DVT prophylaxis in the acute to subacute period is Wu et al generally safe. A prospective safety and efficacy study of SQ anticoagulants in patients with ICH is warranted. DVT Prophylaxis Does Not Increase ICH Volume 6. Sources of Funding This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Training Grant 5 T32 NS007412-12, Specialized Program for Translational Research in Acute Stroke (SPOTRIAS) Grant P50 NS 044227, the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, and the American Heart Association 0475008N. Disclosures 7. 8. None. 9. References Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 1. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38: 1655–1711. 2. Skaf E, Stein PD, Beemath A, Sanchez J, Bustamante MA, Olson RE. Venous thromboembolism in patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1731–1733. 3. Warlow C, Ogston D, Douglas AS. Deep venous thrombosis of legs after strokes: Part I—incidence and predisposing factors. Part II—natural history. BMJ. 1976;1178 –1183. 4. Ogata T, Yasaka M, Wakugawa Y, Inoue T, Ibayashi S, Okada Y. Deep venous thrombosis after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2008;272:83– 86. 5. Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Morgenstern L, Ogilvy CS, Vespa P, Zuccarello M. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Adults 2007 Update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 709 Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke. 2007;38:2001–2023. Orken DN, Gulay Kenangil G, Ozkurt H, Guner C, Gundogdu L, Basak M, Forta H. Prevention of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurologist. 2009;15:329 –331. Kiphuth, IC, Staykov D, Kohrmann M, Struffert T, Ricter G, Bardutzky J Kollmar R, Maurer M, Schellinger PD, Hilz MJ, Doerfler A, Schwab S, Huttner HB. Early administration of low molecular weight heparin after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage—a safety analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:146 –150. Boeer A, Voth E, Henze TH, Prange HW. Early heparin therapy in patients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:466 – 467. Dickman U, Voth E, Schicha H, Henze TH, Prange HW, Emrich D. Heparin therapy, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after intracerebral hemorrhage. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1988:1182–1183. Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: incidence and time course. Stroke. 1996;27:1783–1787. Lim JK, Hwang HS, Cho BM, Lee HK, Ahn SK, Oh SM, Choi SK. Multivariate analysis of risk factors of hematoma expansion in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:40 – 45. Huttner HB, Steiner T, Hartmann M, Köhrmann M, Juettler E, Mueller S, Wikner J, Meyding-Lamade U, Schramm P, Schwab S, Schellinger PD. Comparison of ABC/2 estimation technique to computer-assisted planimetric analysis in warfarin-related intracerebral parenchymal hemorrhage. Stroke. 2006;37:404 – 408. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666 – 670. Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, Spilker J, Duldner J, Khoury J. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. Lacut K, Bressollette L, Le Gal G, Etienne E, De Tinteniac A, Renault A, Rouhard F, Besson G, Garcia JF, Mottier D, Oger E. Prevention of venous thrombosis in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2005;65:865– 869. Kazui SMK, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Predisposing factors to enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Stroke. 1997;28: 2370 –2375. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Pharmacological Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis Does Not Lead to Hematoma Expansion in Intracerebral Hemorrhage With Intraventricular Extension Tzu-Ching Wu, Mallik Kasam, Nusrat Harun, Hen Hallevi, Hesna Bektas, Indrani Acosta, Vivek Misra, Andrew D. Barreto, Nicole R. Gonzales, George A. Lopez, James C. Grotta and Sean I. Savitz Stroke. 2011;42:705-709; originally published online January 21, 2011; doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600593 Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/42/3/705 Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/03/12/STROKEAHA.110.600593.DC2.html http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/02/28/STROKEAHA.110.600593.DC1.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ La profilaxis farmacológica de la trombosis venosa profunda no conduce a una expansión del hematoma en la hemorragia intracerebral con extensión intraventricular Tzu-Ching Wu, MD; Mallik Kasam, PhD; Nusrat Harun, MS; Hen Hallevi, MD; Hesna Bektas, MD; Indrani Acosta, MD; Vivek Misra, MD; Andrew D. Barreto, MD; Nicole R. Gonzales, MD; George A. Lopez, MD; James C. Grotta, MD; Sean I. Savitz, MD Antecedentes y objetivo—Los pacientes con hemorragia intracerebral (HIC) tienen un riesgo elevado de presentar una trombosis venosa profunda. Las guías actuales afirman que puede considerarse el uso de dosis bajas subcutáneas de heparinas de bajo peso molecular o heparina no fraccionada a los 3 a 4 días del inicio. Sin embargo, no hay datos suficientes sobre el volumen de hematoma en los pacientes con HIC antes y después de la profilaxis farmacológica de la trombosis venosa profunda, y ello crea incertidumbre en los médicos respecto a la seguridad de esta práctica. Métodos—Identificamos a los pacientes de nuestro registro de ictus (junio de 2003 a diciembre de 2007) que presentaron una HIC sola o una HIC + hemorragia intraventricular y recibieron o bien heparina de bajo peso molecular por vía subcutánea o bien heparina no fraccionada en un plazo de 7 días tras el ingreso, y en los que se obtuvo una nueva TC en los 4 días siguientes al inicio de la profilaxis de la trombosis venosa profunda. Calculamos el cambio del volumen del hematoma entre la TC de ingreso y la TC posterior al tratamiento. El volumen del hematoma se calculó utilizando el método ABC/2 y los volúmenes de hemorragia intraventricular se calcularon con un método publicado de delimitación manual de las regiones de interés. Resultados—Identificamos a 73 pacientes de una media de edad de 63 años y con una mediana de 11,5 en la puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale. La media basal del volumen total de hematoma fue de 25,8 mL ± 23,2 mL. Se observó un cambio absoluto del volumen del hematoma entre la TC previa y la posterior al tratamiento de -4,3 mL ± 11,0 mL. Dos pacientes presentaron un crecimiento del hematoma. Un nuevo análisis de los pacientes que recibieron profilaxis farmacológica de la trombosis venosa profunda en un plazo de 2 o de 4 días tras la HIC no mostró aumento alguno del tamaño del hematoma. Conclusiones—La profilaxis farmacológica de la trombosis venosa profunda administrada por vía subcutánea en pacientes con HIC y/o hemorragia intraventricular en el periodo subagudo no se asocia generalmente a un crecimiento del hematoma. (Traducido del inglés: Pharmacological Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis Does Not Lead to Hematoma Expansion in Intracerebral Hemorrhage With Intraventricular Extension. Stroke. 2011;42:705-709.) Palabras clave: anticoagulants n DVT prophylaxis n intracerebral hemorrhage L gativas de una enfermedad ya de por sí letal, que tiene una tasa de letalidad a un mes del 35% al 52%5. La TVP prolonga también la duración de la hospitalización, retrasa los programas de rehabilitación e introduce un posible riesgo de EP6. Las actuales guías de American Heart Association/American Stroke Association para el ictus isquémico agudo recomiendan la administración de anticoagulantes subcutáneos (s.c.) como la heparina no fraccionada (HNF) o la heparina de bajo peso molecular (HBPM) para prevenir la TVP en pacientes inmovilizados1. En cambio, las guías de American Heart Association/American Stroke Association para el ictus hemorrágico son menos claras al indicar que puede considerarse el empleo de anticoagulantes subcutáneos a los 3 a 4 días del inicio, tras haber documentado el cese de la hemorragia5. Esta recomendación tibia deriva del hecho de que hay os pacientes con hemorragia intracerebral (HIC) o ictus isquémico presentan un riesgo elevado de desarrollar una tromboembolia venosa (TEV)1. En comparación con los pacientes con ictus isquémico, el riesgo de TEV es mayor en la población de pacientes con ictus hemorrágicos2. El riesgo de TEV se ve potenciado también por la inmovilización y la paresia de las extremidades inferiores y por la identificación tardía de los eventos trombóticos subclínicos. Sin medidas preventivas, el 53% y el 16% de los pacientes inmovilizados sufren trombosis venosa profunda (TVP) o embolia pulmonar (EP), respectivamente, en esa población3. En un estudio se detectó la presencia de TVP en el 40% de los pacientes con HIC en un plazo de 2 semanas y el 1,9% de estos pacientes presentaron una EP4. La aparición de un TEV en el paciente con HIC aumenta aún más las complicaciones ne- Este artículo permite obtener créditos de formación médica continuada (CME). Responda al cuestionario en http://cme.ahajournals.org Recibido el 20 de agosto de 2010; aceptado el 1 de octubre de 2010. Department of Neurology, University of Texas–Houston Medical School, Houston, TX. Remitir la correspondencia a Sean I. Savitz, MD, Department of Neurology, The University of Texas–Houston Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street Suite, Houston, TX 77030. Correo electrónico [email protected] © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke está disponible en http://www.stroke.ahajournals.org 74 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.600593 Wu y cols. La profilaxis de la TVP no conduce a expansión del hematoma en la HIC 75 Figura 1. Diseño y población del estudio. una falta de ensayos controlados y aleatorizados amplios que aborden la prevención del TEV en la población con HIC y son menos aún los datos disponibles respecto a los pacientes con hemorragia intraventricular (HIV). En consecuencia, no hay un consenso respecto a cómo y cuándo iniciar la profilaxis de la TVP para prevenir las complicaciones de TEV en la población con HIC y/o HIV. La preocupación por la posibilidad de que los anticoagulantes puedan aumentar el tamaño del hematoma y causar un empeoramiento neurológico hace surgir muchas dudas7. Se han publicado 2 ensayos prospectivos y aleatorizados pequeños sobre el uso temprano de heparina en la HIC, y ninguno de ellos ha mostrado un aumento del riesgo de hemorragia8,9. Un ensayo prospectivo y aleatorizado recientemente publicado comparó el uso temprano de HBPM y las medias de compresión en pacientes con HIC y no observó aumento alguno del crecimiento del hematoma en ninguno de los dos grupos6. Sin embargo, el número de pacientes de estos estudios fue bajo y no se obtuvieron TC posteriores de manera sistemática en todos los casos para documentar la posible recurrencia del sangrado. Dada la falta de datos y la preocupación existente por la posibilidad de expansión del hematoma, los médicos se encuentran en una situación de incertidumbre por lo que respecta a la seguridad de esa práctica10,11. Este estudio retrospectivo tuvo como objetivo evaluar la seguridad de los anticoagulantes s.c. en la población con HIC y/o HIV y su asociación con el crecimiento del hematoma. Métodos Diseño y población del estudio Se realizó una búsqueda retrospectiva en nuestro registro de ictus para los datos obtenidos de forma prospectiva entre junio de 2003 y diciembre de 2007, con objeto de identificar a todos los pacientes con un diagnóstico de HIC. Se excluyó a los pacientes en los que la etiología de la HIC era una masa, una malformación arteriovenosa, un aneurisma o indeterminada. Se diagnosticó una HIC hipertensiva si los pacientes tenían antecedentes de hipertensión arterial con una localiza- ción de la hemorragia típica en las exploraciones de imagen. Las hemorragias amiloides se diagnosticaron utilizando la información clínica, incluidos los antecedentes de hipertensión arterial, la presión arterial en el momento de la presentación inicial y a lo largo de toda la hospitalización y las exploraciones de imagen de apoyo. Las hemorragias asociadas a coagulopatías se diagnosticaron en los pacientes con una HIC en presencia de una ratio normalizada internacional elevada al ingreso. Se clasificó a los pacientes en el grupo de etiología indeterminada si no estaba claro que la etiología fuera hipertensiva, amiloidea o de ambos tipos, en función de los datos clínicos y radiológicos. Los pacientes fueron incluidos en el análisis después de que la revisión de la historia clínica confirmara la HIC y/o HIV al ingreso, y que habían recibido HBPM s.c. o HNF s.c. en un plazo de 7 días tras el ingreso y disponían de una TC posterior obtenida en los 4 días siguientes al inicio de la profilaxis de la TVP. Se utilizó el criterio de un tratamiento en los 7 días siguientes al ingreso porque las directrices para iniciar la profilaxis de la TVP no son claras y también para capturar las tendencias de prescripción de nuestro centro. El criterio de disponibilidad de una TC en los 4 días siguientes al inicio de la profilaxis de la TVP se eligió para tener en cuenta la variabilidad existente a la hora de realizar las exploraciones de imagen después del tratamiento, dado que se trata de un análisis retrospectivo. Se llevó a cabo un análisis por separado en los pacientes que recibieron HBPM s.c. o HNF s.c. en un plazo de 2 días y de 4 días tras el ingreso, y según el diagnóstico (HIC solamente, HIC+HIV). Se revisaron las historias clínicas de los pacientes que cumplían los criterios del estudio (Figura 1), con objeto de determinar las características demográficas basales y obtener una información clínica que incluía la puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale al ingreso y la puntuación de la escala de Rankin modificada al alta. Tratamiento Los pacientes con HIC y/o HIV fueron tratados según lo indicado por las guías de American Heart Association/American 76 Stroke Julio 2011 Tabla 1. Características clínicas y radiológicas de los pacientes tratados con profilaxis farmacológica de la TVP en los 7 primeros días siguientes al ingreso Características basales Total de pacientes (n = 73) Pacientes sin DVE (n = 52) 63 (37–93) 63 (37– 87) Media de edad, años (rango) Sexo, varones/mujeres Mediana (rango) de NIHSS al ingreso 40/33 29/23 11,5 (0–40) 10 (0–40) Mediana (rango) de mRS al alta DVE, % 4 (0–6) 4 (0–6) 21 (29%) 0 TVP o EP, % Características radiológicas 0 0 VH total VH de HIC sola Media (rango) de VH al ingreso, mL 25,8 23,2 (0,6–90) 17,6 19,3 (0–90) Media (rango) de VH post-tratamiento, mL 21,6 22,6 (0,5–108) 17,3 20,4 (0–108) Media (rango) de ∆ del VH, mL 4,3 11,0 ( 41,9–23,5) 0,3 8,8 ( 35–38) (P 0,0015) (P 0,77) VH total 19,5 20,3 (0,6–90) 18 18,9 (0,7–80) 1,5 6,8 ( 35,0–19,2) (P 0,69) Localización Profunda, % 47 (64%) 31 (60%) Lobular, % 14 (20%) 12 (23%) Otras,* % 12 (16%) 9 (17%) Profilaxis de TVP Enoxaparina, % 50 (69%) 37 (71%) Heparina, % 20 (27%) 12 (23%) 3 (4%) 3 (6%) Dalteparina, % *Otras indica cerebelosa, tronco encefálico, HIV primaria. NIHSS indica National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, escala de Rankin modificada; DVE, drenaje ventricular externo. Stroke Association5 y no recibieron Factor VII ni activador de plasminógeno tisular intraventricular; sin embargo, no se protocolizaron estrictamente las presiones arteriales en el periodo agudo post-hemorragia. En los pacientes que presentaron una hidrocefalia obstructiva, se colocó un drenaje ventricular externo. En nuestro centro se utilizaron dos formas de anticoagulación s.c. durante este periodo (HBPM = 40 mg de enoxaparina o 5.000 U de dalteparina s.c. una vez al día, HNF = 5.000 U de heparina s.c. 2 a 3 veces al día). La preferencia por la medicación y el momento de administración se dejaron a criterio del médico encargado del paciente. Se utilizaron dispositivos de compresión intermitente en todos los pacientes. Radiología Todas las TC se realizaron con el empleo de una técnica idéntica (grosor de corte, 5 mm; inclinación de soporte, 16). Las TC de ingreso fueron examinadas por los autores para confirmar la HIC y/o HIV. Todos los cálculos del volumen del hematoma fueron realizados por un mismo autor que no conocía el tratamiento asignado ni el resultado evaluado en el estudio. Se calculó el volumen de HIC en el interior del parénquima utilizando el método ABC/212. El volumen de HIV se calculó utilizando un método publicado de delimitación manual de regiones de interés en cada área de presencia de sangre intraventricular de cada corte, multiplicado por el grosor del corte y sumado para obtener el volumen total de HIV13. Se tomó como volumen total de hematoma (VH) la suma del volumen de HIC y el volumen de HIV. El cambio del VH (∆vol) se definió como la diferencia entre el VH to- tal en la primera TC post-tratamiento y el VH total de la TC de ingreso. La localización del hematoma se clasificó como profunda (tálamo, putamen, caudado), lobular u otros (HIV primaria, cerebeloso o de tronco encefálico). Crecimiento del hematoma Decidimos utilizar como variable de valoración primaria el crecimiento absoluto del hematoma y considerar el crecimiento significativo del hematoma como variable secundaria. El crecimiento significativo del hematoma se definió como un cambio del VH > 33% y un cambio absoluto del volumen ≥ 5 mL. Utilizamos el criterio de un cambio de volumen > 33%, ya que corresponde a un aumento del 10% del diámetro de una esfera y se ha utilizado ya en estudios previos de crecimiento del hematoma14. Se utilizó un ∆vol absoluto de Figura 2. Distribución de la fecha de inicio de la profilaxis farmacológica de la TVP. Wu y cols. La profilaxis de la TVP no conduce a expansión del hematoma en la HIC 77 Tabla 2. Características clínicas y radiológicas de los pacientes tratados con profilaxis farmacológica de la TVP en los 4 y los 2 primeros días siguientes al ingreso Características basales Media de edad, años (rango) En 4 Días (n = 50) En 2 Días (n = 24) 62,78 (37–93) 63,91 (40 –93) Sexo, varones/mujeres 28/22 Mediana (rango) de NIHSS al ingreso Mediana (rango) de mRS al alta 9 (0–40) 4, 5 (0–6) 5 (1–6) DVE, % 10 (20%) 3 (12,5%) Radiología Características VH total 10/14 8, 5 (1–40) VH total Media (rango) de volumen en TC inicial, mL 21,6 22,7 (0,60–85,5) 20,1 18,9 (0,6–75) Media (rango) de volumen en TC final, mL 20,3 24,4 (0,5–109) 19,5 19,7 (0,7–69) Media (rango) de ∆ de volumen en la TC, mL 1,3 8,9 ( 30,7–23,5) (P 0,31) 0,65 5,2 ( 18,5–12,9) (P 0,54) Localización Profunda, % 30 (60%) 14 (58%) Lobular, % 11 (22%) 8 (33) Otras,* % 9 (18%) 2 (8%) Enoxaparina, % 37 (74%) 19 (79%) Heparina, % 12 (24%) 5 (21%) 1 (2%) 0 (0%) Profilaxis de TVP Dalteparina, % *Otras indica cerebelosa, tronco encefálico, HIV primaria. NIHSS indica National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; mRS, escala de Rankin modificada. 5 mL como valor de corte ya que los autores consideraron que un ∆vol ≤ 5 mL era una causa improbable de deterioro clínico y también para tener en cuenta la imprecisión en el cálculo del volumen del hematoma utilizando la TC. Análisis estadístico Con el empleo del valor de corte de 5 mL y la DE de nuestros datos (25 mL), se realizaron cálculos del tamaño muestral/ potencia estadística y se demostró que, con una correlación de 0,85, serían necesarios 61 pacientes para disponer de una potencia estadística del 80% en la detección de un ∆vol de 5 mL. Se utilizaron las medias con DE o las medianas para las variables continuas. Las diferencias se evaluaron con pruebas de t, pruebas de χ2, la prueba exacta de Fisher o la prueba de U de Mann-Whitney. Se utilizó un nivel de significación de 0,05 para evaluar la diferencia estadística. El análisis estadístico se realizó con el programa SAS 9. Resultados Identificamos a 73 pacientes que cumplían los criterios del estudio. Las características clínicas y radiológicas basales se indican en la Tabla 1. La media de edad era de 63 años y la mediana de la puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale al ingreso era de 11,5. Un total de 50 pacientes (69%) recibieron enoxaparina, 20 pacientes (27%) recibieron HNF y 3 pacientes (4%) recibieron dalteparina. El tiempo transcurrido entre el ingreso por HIC y la administración de la profilaxis para la TVP fue también diverso; la mayoría de las profilaxis de la TVP se administraron entre los días 2 y 5 (Figura 2). Globalmente, hubo un ∆vol absoluto entre la TC previa y la posterior al tratamiento de -4,3 mL ± 11,0 mL (p = 0,0015). Al analizar solamente la parte de HIC del hematoma en la totalidad de los 73 pacientes se observó un ∆vol absoluto de -0,3 mL ± 8,8 mL (p = 0,77). En los pacientes en los que no se colocó un drenaje ventricular externo, el ∆vol absoluto fue de -1,5 mL ± 6,8 mL (p = 0,69). Dos pacientes (2,7%) presentaron un crecimiento significativo del hematoma en el periodo de estudio. Uno de ellos recibió HBPM y el otro HNF, y en ambos casos la etiología de la hemorragia era la hipertensión arterial. No se identificó ningún patrón en lo relativo a las características clínicas y radiológicas de estos 2 pacientes que presentaron un crecimiento significativo del hematoma. Analizamos por separado a los pacientes que recibieron una profilaxis de la TVP en un plazo de 4 días tras el ingreso, y los resultados mostraron un ∆vol absoluto entre la TC previa y la posterior al tratamiento de -1,3 mL ± 8,9 mL (p = 0,31; Tabla 2). En los pacientes que recibieron la profilaxis de la TVP en un plazo de 2 días tras el ingreso, los datos mostraron un ∆vol absoluto entre la TC previa y la posterior al tratamiento de -0,65 mL ± 5,2 mL (p = 0,54; Tabla 2). Discusión Que nosotros sepamos, este estudio es el primero en el que se presenta el crecimiento del hematoma en relación con el uso de anticoagulantes s.c. para la prevención de la TVP en la población con HIC y HIV. En el estudio recientemente publicado por Orken y cols., estos autores estudiaron la seguridad de HBPM y de las medias de compresión para la profilaxis de la TVP y sus efectos sobre el crecimiento del hematoma en los pacientes con HIC. Se observó que el tratamiento con HBPM (n = 39) y el empleo de medias de compresión (n = 36) para la prevención de la TVP/EP no se asociaban a un crecimiento del hematoma, pero no se indicó la frecuencia de HIC en la población en estudio ni el tiempo transcurrido hasta la administración de la medicación, más allá de que se administró después de las primeras 48 horas6. Comparativamente, la mayoría de nuestros pacientes iniciaron el tratamiento de anticoagulación en menos de 2 a 5 días tras la hemorragia, y un 28% (n = 20) recibieron anticoagulantes en las primeras 48 horas siguientes al ingreso. En general, observamos que la administración de una profilaxis farmacológica para la TVP por vía s.c. en el periodo agudo (2 a 4 días) a subagudo (≤ 7 días) no se asoció a un crecimiento del hematoma. Los pacientes de nuestro estudio tenían tamaños de hematoma diversos, de entre 0,5 mL y 90 mL. Sin embargo, en el periodo subagudo, 2 pacientes presentaron una expansión significativa del hematoma, pero no fue posible identificar ningún patrón o factor que se asociara al crecimiento del hematoma. No se observó tampoco un crecimiento del hematoma al dividir la población de pacientes según el diagnóstico (HIC sola o HIC + HIV) ni según la presencia de un drenaje ventricular externo. Sin embargo, la diferencia de ∆vol en el grupo de HIC sola fue mucho menor que en el grupo de HIC + HIV, lo cual confirmaba que la HIV desempeña un papel en la resolución del hematoma. De los 36 pacientes con HIC+HIV, en 21 78 Stroke Julio 2011 se había colocado un drenaje ventricular externo y solamente identificamos a 1 paciente que presentó una hemorragia alrededor del catéter. En consecuencia, la instauración de un tratamiento con anticoagulantes s.c. en pacientes con drenajes ventriculares externos puede ser seguro, con unas tasas de complicaciones bajas. Sin embargo, nuestros datos no indican que los pacientes que fueron tratados en el periodo agudo tuvieran una mediana de puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale al ingreso inferior (9 antes del Día 4, 8,5 antes del Día 2) a la mediana de puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale de 11,5 observada en los pacientes tratados antes del Día 7 de ingreso. Esto puede indicar que hay una tendencia a retrasar la instauración de la anticoagulación s.c. en los pacientes con HIC en estado más grave o posiblemente que los pacientes con una puntuación más alta de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale al ingreso tienden a presentar recurrencias hemorrágicas tempranas que hacen que la administración de la anticoagulación s.c. sea más tardía. Las guías actuales para el tratamiento de la HIC recomiendan el empleo de compresión neumática intermitente para la prevención del TEV, y se ha demostrado que su uso resulta eficaz15. Aunque no hay datos aleatorizados, la adición de anticoagulantes s.c. a los dispositivos de compresión neumática intermitente debe aportar una protección adicional frente a la aparición del TEV. La amplia disponibilidad, el bajo coste y la eficacia probada de los anticoagulantes s.c. para la prevención del TEV pueden reducir las complicaciones de este tipo en la población con HIC/HIV altamente vulnerable. Nuestro estudio se suma a la literatura limitada existente y respalda nuevamente la seguridad de los anticoagulantes en el periodo agudo y subagudo tras la HIC. Sin embargo, el estudio tiene la limitación de su naturaleza retrospectiva, el tamaño muestral pequeño y la inexactitud inherente a la medición del volumen del hematoma en la TC. Con la muestra pequeña utilizada, no fue posible evaluar la eficacia de HBPM s.c. o HNF s.c. en la prevención de la TVP o la EP; sin embargo, no se observó ningún caso de EP o TVP en la población en estudio. En la reducción global observada del hematoma puede haber contribuido en gran parte el drenaje de ventriculostomía y/o la regresión natural del propio hematoma; sin embargo, al examinar la parte de HIC de la totalidad de los 73 pacientes del estudio, no se observó un crecimiento del hematoma. Otro factor de confusión importante puede ser el control de la presión arterial, puesto que algunos autores han propuesto que el crecimiento del hematoma se asocia al grado de control de la hipertensión en los pacientes con HIC16. Los criterios de inclusión del estudio pueden haber influido en nuestros datos y resultados. En primer lugar, tan solo incluimos a pacientes que recibieron profilaxis para la TVP. Este sesgo de selección puede haber excluido a los pacientes que presentaron hemorragias más graves, con la posibilidad de un crecimiento temprano del hematoma, en los que el médico encargado puede haber optado por no utilizar anticoagulantes. Y a la inversa, al incluir solamente a pacientes en los que se habían realizado exploraciones de imagen de seguimiento, podemos haber descartado a una población de pacientes estables que recibieron anticoagulantes s.c. y que se mantuvieron clínicamente estables, y no requirieron por tanto una TC de seguimiento. Esto puede haber motivado que en este estudio estuvieran sobrerrepresentados los pacientes con crecimientos del hematoma, puesto que la obtención de exploraciones de imagen de seguimiento es más probable en los pacientes que presentan un deterioro clínico. Finalmente, al optar por analizar solamente el volumen del hematoma de la primera TC posterior al tratamiento, limitamos nuestra capacidad de detectar una expresión tardía del hematoma. En conclusión, los datos de este estudio sugieren que la administración s.c. de HBPM o HNF en pacientes con HIC y/o HIV para la profilaxis de la TVP en el periodo agudo o subagudo es generalmente segura. Está justificado un estudio prospectivo de la seguridad y la eficacia de los anticoagulantes s.c. en pacientes con HIC. Fuentes de financiación Este estudio fue financiando por National Institutes of Health Training Grant 5 T32 NS007412-12, Specialized Program for Translational Research in Acute Stroke (SPOTRIAS) Grant P50 NS 044227, el Howard Hughes Medical Institute, y la American Heart Association 0475008N. Declaraciones de conflictos de intereses Ninguna. Bibliografía 1. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38: 1655–1711. 2. Skaf E, Stein PD, Beemath A, Sanchez J, Bustamante MA, Olson RE. Venous thromboembolism in patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:1731–1733. 3. Warlow C, Ogston D, Douglas AS. Deep venous thrombosis of legs after strokes: Part I—incidence and predisposing factors. Part II—natural history. BMJ. 1976;1178 –1183. 4. Ogata T, Yasaka M, Wakugawa Y, Inoue T, Ibayashi S, Okada Y. Deep venous thrombosis after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2008;272:83– 86. 5. Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg M, Morgenstern L, Ogilvy CS, Vespa P, Zuccarello M. Guidelines for the Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Adults 2007 Update: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke. 2007;38:2001–2023. 6. Orken DN, Gulay Kenangil G, Ozkurt H, Guner C, Gundogdu L, Basak M, Forta H. Prevention of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurologist. 2009;15:329 –331. 7. Kiphuth, IC, Staykov D, Kohrmann M, Struffert T, Ricter G, Bardutzky J Kollmar R, Maurer M, Schellinger PD, Hilz MJ, Doerfler A, Schwab S, Huttner HB. Early administration of low molecular weight heparin after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage—a safety analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:146 –150. 8. Boeer A, Voth E, Henze TH, Prange HW. Early heparin therapy in patients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:466 – 467. 9. Dickman U, Voth E, Schicha H, Henze TH, Prange HW, Emrich D. Heparin therapy, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after intracerebral hemorrhage. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1988:1182–1183. 10. Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: incidence and time course. Stroke. 1996;27:1783–1787. 11. Lim JK, Hwang HS, Cho BM, Lee HK, Ahn SK, Oh SM, Choi SK. Multivariate analysis of risk factors of hematoma expansion in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:40 – 45. Dis. 2009;27:146 –150. Wikner J, Meyding-Lamade U, Schramm P, Schwab S, Schellinger PD. 8. Boeer A, Voth E, Henze TH, Prange HW. Early heparin therapy in Comparison of ABC/2 estimation technique to computer-assisted planipatients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg metric analysis in warfarin-related intracerebral parenchymal hemorPsychiatry. 1991;54:466 – 467. rhage. Stroke. 2006;37:404 – 408.del hematoma en la HIC 79 Wu y cols. La profilaxis de la TVP no conduce a expansión 9. Dickman U, Voth E, Schicha H, Henze TH, Prange HW, Emrich D. 13. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Heparin therapy, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage intracerebral hemorrhage. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1988:1182–1183. trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666 – 670. 10. Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. 14. Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, Enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: incidence and Spilker J, Duldner J, Khoury J. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with time course. Stroke. 1996;27:1783–1787. intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. 11. Lim JK, Hwang HS, Cho BM, Lee HK, Ahn SK, Oh SM, Choi SK. 15. Lacut K, Bressollette L, Le Gal G, Etienne E, De Tinteniac A, Renault A, Multivariate analysis of risk factors of hematoma expansion in sponRouhard F, Besson G, Garcia JF, Mottier D, Oger E. Prevention of venous taneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:40 – 45. thrombosis in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 12. Huttner HB, Steiner T, Hartmann M, Köhrmann M, Juettler E, Mueller S, 2005;65:865– 869. Wikner J, Meyding-Lamade U, Schramm P, Schwab S, Schellinger PD. 16. Kazui SMK, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Predisposing factors to Comparison of ABC/2 estimation technique to computer-assisted planienlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Stroke. 1997;28: metric analysis in warfarin-related intracerebral parenchymal hemor2370 –2375. rhage. Stroke. 2006;37:404 – 408. 13. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666 – 670. 14. Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, Spilker J, Duldner J, Khoury J. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. 15. Lacut K, Bressollette L, Le Gal G, Etienne E, De Tinteniac A, Renault A, Rouhard F, Besson G, Garcia JF, Mottier D, Oger E. Prevention of venous thrombosis in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2005;65:865– 869. 16. Kazui SMK, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Predisposing factors to enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Stroke. 1997;28: 2370 –2375. Wu et al DVT Prophylaxis Does Not Increase ICH Volume Original Contributions 药物预防深静脉血栓不会导致伴脑室出血的脑出血的血肿扩大 Pharmacological Deep Vein Thrombosis Prophylaxis Does Not Lead to Hematoma Expansion in Intracerebral Hemorrhage With Intraventricular Extension Tzu-Ching Wu, MD; Mallik Kasam, PhD; Nusrat Harun, MS; Hen Hallevi, MD; Hesna Bektas, MD; Indrani Acosta, MD; Vivek Misra, MD; Andrew D. Barreto, MD; Nicole R. Gonzales, MD; George A. Lopez, MD; James C. Grotta, MD; Sean I. Savitz, MD 背景和目的 :脑出血 (ICH) 患者是发生深静脉血栓的高危人群。当前的指南指出发病 3 到 4 天可以考虑皮下 注射小剂量的低分子肝素或普通肝素。然而,有关脑出血患者药物预防深静脉血栓前后的血肿体积变化并没 有充分的证据,使得医生不确定这项措施的安全性。 方法:我们选取了从 2003 年 7 月至 2007 年 12 月在我们卒中登记中记录的脑出血或脑出血合并脑室出血的患者, 均在入院 7 天内予以注射低分子肝素或普通肝素,并且在药物预防深静脉血栓 4 天内复查 CT,我们计算了患 者入院及复查 CT 上的血肿体积变化,血肿体积的计算使用 ABC/2 法,脑室出血量的计算则使用发表的手绘 出血区域方法。 结果 :共有患者 73 例,平均年龄 63 岁,其 NIHSS 评分中位值为 11.5,基线时血肿体积平均为 25.8 mL±23.2 mL, 前后 CT 检查上的血肿体积有绝对变化,为 –4.3 mL±11.0 mL。2 例患者的血肿体积增大。经反复分析,ICH 发病 2 或 4 天内给予药物预防深静脉血栓并不导致血肿的增大。 结论 :在脑出血伴 / 不伴脑室出血的亚急性期,给予皮下注射预防深静脉血栓通常不导致血肿的增大。 关键词 :抗凝剂,深静脉血栓预防,脑出血 (Stroke. 2011;42:705-709. 上海交通大学医学院附属仁济医院神经科 王飞 译 李焰生 校 ) 脑出血 (ICH) 或缺血性卒中患者极易发生静脉 血栓栓塞 (VTE)[1],且脑出血者的危险高于缺血性 剂 [5]。这种 “ 不积极的推荐 ” 源于缺乏大规模的关 于脑出血患者预防 VTE 的随机对照试验,关于脑室 卒中者 [2]。由于下肢瘫痪、不动或亚临床的血栓事 出血 (IVH) 的研究数据则更少。因此,关于在 ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH 患者如何及何时开始 DVT 预防以减少 件识别延缓,VTE 更易发生。若没有预防性措施, 这些患者中的 53% 和 16% 将分别发生深静脉血栓 (DVT) 或肺栓塞 (PE) 。一项研究发现,在脑出血 发病 2 周内,40% 患者发生 DVT,1.9% 发生 PE[4]。 [3] 静脉血栓的形成将恶化致死性的脑出血,使得 1 个 月的病死率由 35% 升至 52%[5]。DVT 也会延长住院 时间、延缓康复实施、增加 PE 的风险 [6]。 目前,美国心脏病学会 / 美国卒中学会的急性 缺血性卒中指南,推荐皮下使用抗凝剂,如普通肝 素 (UFH) 或低分子肝素 (LMWH),以预防长期不动 患者发生 DVT 。另一方面,美国心脏病学会 / 美国 [1] 卒中学会的出血性卒中指南,并未明确地指出,发 病 3 到 4 天,出血停止后,能否考虑皮下注射抗凝 VTE 的并发症,目前尚无一致意见。 主要的担忧来自于担心抗凝剂的使用会使血肿 扩大,导致神经功能恶化 [7]。有两项关于脑出血早 期使用肝素的小规模的前瞻性随机研究显示并不增 加出血风险 [8,9]。最近的一项前瞻性随机研究,发现 脑出血患者早期使用 LMWH 或弹力袜都不增加出血 的风险。然而,这些研究中的患者数都很少,也并 未都复查 CT 以确定是否有再出血。总之,缺少资 料和担心血肿扩大,使得医生不能确定这项措施的 安全性 [10,11]。 本回顾性研究目的是评估 ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH 患者 皮下注射抗凝剂的安全性及其与血肿扩大的关系。 Continuing medical education (CME) credit is available for this article. Go to http://cme.ahajournals.org to take the quiz. From the Department of Neurology, University of Texas–Houston Medical School, Houston, TX. Correspondence to Sean I. Savitz, MD, Department of Neurology, The University of Texas–Houston Medical School, 6431 Fannin Street Suite, Houston, TX 77030. E-mail [email protected] © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. 39 Stroke March 2011 2003 年 7 月至 2007 年 12 月卒中登记中诊断为 脑出血的所有患者 N=859 动脉瘤 (N=13) 动静脉畸形 (N=12) 肿瘤 (N=56) 病因不明 (N=214) 高血压 (N=485) 淀粉样变性 (N=27) 凝血功能障碍 (N=52) 病因 入院 7 天内接受皮下 注射低分子肝素或 普通肝素,且在深 静脉血栓预防 4 天内 复查头颅 CT 排除 是 (N=73) 淀粉样变性 (N=7) 高血压 (N=61) 凝血功能障碍 (N=5) 否 (N=491) 研究人群 (N=73) 排除 方法 图 1 研究设计和人群 国卒中协会的指南 [5] 治疗,未予以Ⅶ因子 或 rt-PA ; 研究设计与研究人群 对出血急性期的血压并未严格控制。对有阻塞性脑 此项回顾性研究,搜集了我们 2003 年 7 月至 2007 年 12 月前瞻性卒中登记中诊断为 ICH 的患者。 积水患者予以体外脑室引流。DVT 预防用药期间给 予两种形式的处理 (LMWH=40 mg 依诺肝素或 5000 有以下病因者不入选 :肿瘤、动静脉畸形、动脉瘤 U 达肝素钠皮下注射,每日一次 ;普通肝素 =5000 以及未明确的病因。若有高血压病史且影像学有典 U 肝素钠皮下注射,每日 1-2 次 )。药物的选择及服 型出血部位即诊断为高血压性脑出血。淀粉样变性 药时间则由其经治医生决定。对每位患者均配有间 脑出血的诊断则主要靠临床方面的信息,包括高血压 歇性加压设备。 病史、发病及住院过程中的血压及影像学的支持。如 果脑出血患者入院时的国际标准化比率升高,则诊断 影像学 为凝血功能障碍相关的脑出血。如果病因不能确定为 所有的 CT 均使用相同的设备 ( 层厚 5 mm,机 架倾斜 16)。入院时的 CT 片由本研究者阅读以证实 高血压性、淀粉样变性,或根据临床或影像学资料证 明二者均有,则归类于不能明确病因的脑出血。 入院后确诊为 ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH,在入院 7 天内 予以皮下注射低分子肝素或普通肝素,并且在药物 预防深静脉血栓 4 天内复查 CT 的患者作为研究对 象。选择“入院 7 天内”这个时间段是因为指南上 没有明确说明 DVT 预防起始的时间,也是为了与 我院处方时间的趋势相一致。在 DVT 预防开始 4 天 内复查 CT 是因为考虑到治疗后复查时间的变异性, ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH。所有的出血量均由同一个医师计 算,且其不了解本研究的处理及结果。脑实质血肿 体积的计算使用 ABC/2 法 [12],脑室出血量的计算我 们使用一种公认的手绘出血区域方法,把每个出血 层面的出血面积乘以层厚,再把每个层面相加得到 脑室全部出血量 [13]。脑实质出血量与脑室出血量之 和被认为是总出血量 (HV)。总出血量的改变 (Δvol) 因为这是一个回顾性的研究。对入院 2-4 天内开始 为治疗前第一次 CT 与入院后 CT 的总出血量的改变。 血肿的位置分为深部 ( 丘脑、壳核、尾状核 )、脑叶、 皮下注射低分子肝素或普通肝素的患者,以单独脑 其它 ( 主要包括脑室、小脑、脑干 )。 出血及脑出血合并脑室出血做了单独的研究。对符 合标准 ( 图 1) 的患者做病历总结,统计基线人口学 血肿扩大 及包括入院 NIHSS 分数及出院时改良 Rankin 评分 我们选择血肿绝对扩大为主要结果、明显扩大 的临床信息。 为次要结果。明显扩大定义为出血总体积变化大于 33%,绝对扩大为体积变化大于 5 mL,我们选择变 处理 化值为 33% 是因为它与球直径变化 10% 相一致,并 且它也用于先前的血肿增大的研究 [14]。选择 Δvol=5 ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH 患者按照美国心脏病学会 / 美 40 Wu et al DVT Prophylaxis Does Not Increase ICH Volume 表 1 入院 7 天内接受药物预防 DVT 治疗患者的临床及影像学特征 基本特征 年龄均值,岁 ( 范围 ) 性别,男 / 女 入院 NIHSS 中位数 ( 范围 ) 出院 mRS 中位数 ( 范围 ) 脑室外引流,% DVT 或 PE,% 影像学特征 入院总出血量均值,mL( 范围 ) 治疗后总出血量均值,mL( 范围 ) 出血量变化均值,mL( 范围 ) 总体 (n=73) 63 (37–93) 40/33 11.5 (0–40) 4 (0–6) 21 (29%) 0 仅 ICH 的出血量 17.6±19.3(0–90) 17.3±20.4 (0–108) -0.3±8.8 (-35–38) (P=0.77) 总出血量 25.8±23.2 (0.6–90) 21.6±22.6 (0.5–108) -4.3±11.0 (-41.9–23.5) (P=0.0015) 位置 深部,% 脑叶,% 其它 *,% DVT 预防 依诺肝素,% 肝素钠,% 达肝素钠,% * 其它指小脑、脑干、脑室出血。 未行脑室外引流 (n=52) 63 (37–87) 29/23 10 (0–40) 4 (0–6) 0 0 总出血量 19.5±20.3 (0.6–90) 18±18.9 (0.7–80) -1.5±6.8 (-35.0–19.2) (P=0.69) 47 (64%) 14 (20%) 12 (16%) 31 (60%) 12 (23%) 9 (17%) 50 (69%) 20 (27%) 3 (4%) 37 (71%) 12 (23%) 3 (6%) mL 为绝对扩大的界限是因为我们认为 5 mL 不太可 在研究中,有 2 例患者 (2.7%) 血肿有显著扩大。 能会引起临床症状的恶化,并且也有可能是因为 CT 其中,1 例使用低分子肝素,1 例使用普通肝素,出 不精确的出血量计算引起。 血病因均为高血压。2 例患者的临床及影像学特点 均无特殊。 统计分析 以 5 mL 为界限,数据标准差为 25 mL,对样本 我们对入院 4 天内开始 DVT 预防治疗的患者 做了单独分析,结果显示治疗前后 CT 上出血量有 大小及检验效能的计算等进行了较深入的研究,结 果相关性为 0.85,它要求 61 例患者中有 80% 检测 绝对改变,为 –1.3 mL±8.9 mL(P=0.31,表 2)。对入 院 2 天内接受 DVT 预防治疗的患者,数据显示治疗 到体积变化为 5 mL。我们使用了标准差均数及连续 性变量的中位数。差异分析使用 t 检验、卡方检验、 前后 CT 出血量也有绝对改变,为 –0.65 mL±5.2 mL (P=0.54,表 2)。 Fisher 精确检验或 Mann-Whitney U 检验。统计学差 异以 P=0.05 为水平衡量。统计分析工具为 SAS 9。 讨论 结果 据 我 们 了 解, 在 ICH 和 ( 或 )IVH 患 者 中, 这 是第一篇有关皮下注射抗凝剂预防 DVT 和血肿扩大 我们选取了符合研究标准的 73 例患者。其临床 及影像学特点如表 1。平均年龄 63 岁,入院 NIHSS 相关性的报道。在 Orken 等最近发表的文献中提到, 评分中位数为 11.5。50 例患者 (69%) 使用依诺肝素, 20 例患者 (27%) 使用普通肝素,3 例 (4%) 使用达肝 素钠。从脑出血入院至 DVT 预防用药之间的时间也 是不同的 ;大多数患者的 DVT 预防用药是在入院 后 2-5 天内使用 ( 图 2)。对所有的研究对象来说, 治疗前后 CT 上体积是有绝对改变的,为 –4.3 mL± 患者比例 (%) 11.0 mL (P=0.0015)。在 73 例中,仅 ICH 患者治疗 前 后 体 积 绝 对 改 变 量 为 –0.3 mL±8.8 mL (P=0.77)。 未予以脑室外引流的患者,绝对改变量为 –1.5 mL± 6.8 mL(P=0.69)。 图 2 药物预防 DVT 起始时间分布图 41 Stroke March 2011 表 2 入院 4 天内及 2 天内接受药物预防 DVT 治疗患者的临 床及影像学特征 基本特征 4 天内 (n=50) 2 天内 (n=24) 年龄均值,岁 ( 范围 ) 62.78 (37–93) 63.91 (40–93) 性别,男 / 女 28/22 10/14 入院 NIHSS 中位数 ( 范围 ) 9 (0–40) 8.5 (1–40) 出院 mRS 中位数 ( 范围 ) 4.5 (0–6) 5 (1–6) 脑室外引流,% 10 (20%) 3 (12.5%) 影像学特征 总出血量 总出血量 原 CT 总出血量均值, 21.6±22.7 (0.60–85.5) 20.1±18.9 (0.6–75) mL ( 范围 ) 后 CT 总出血量均值, 20.3±24.4 (0.5–109) 19.5±19.7 (0.7–69) mL ( 范围 ) 出血量变化均值, -1.3±8.9 (-30.7–23.5) -0.65±5.2 (-18.5–12.9) mL ( 范围 ) (P=0.31) (P=0.54) 位置 深部,% 30 (60%) 14 (58%) 脑叶,% 11 (22%) 8 (33) 其它 *,% 9 (18%) 2 (8%) DVT 预防 依诺肝素,% 37 (74%) 19 (79%) 肝素钠,% 12 (24%) 5 (21%) 达肝素钠,% 1 (2%) 0 (0%) * 其它指小脑、脑干、脑室出血。 者倾向于推迟皮下注射抗凝剂,或入院 NIHSS 分值 较高的患者可能会较早出现再出血,从而较晚使用。 目前脑出血治疗指南推荐间歇气压疗法以预防 VTE,并且它的使用已被证实有效 [15]。尽管没有随 机化研究的数据,添加抗凝剂对间歇性加压来说, 也是增加了预防 VTE 的保护措施。在高危 ICH/IVH 患者中,抗凝药的广泛性、低价性及预防 VTE 的有 效性很有可能减少 VTE 的并发症。我们的研究补充 了目前有限的资料,也进一步支持了脑出血急性期 及亚急性期使用抗凝药物的安全性。 然而,由于研究的回顾性、样本小以及 CT 上 计算脑出血量的不精确性,本研究还是具有一定的 局限性。小样本使得我们无法评估皮下注射低分子 肝素或普通肝素以预防 DVT 或 PE 的有效性,但本 研究中无患者发生 DVT 或 PE。观察到的血肿的缩 小有可能很大部分归因于脑室外引流和 / 或血肿自 然的消退。但是当只研究 73 例中仅有 ICH 患者时, 没有出现血肿扩大。另外一个可能的混杂因素就是 血压的控制,因为有人提出假设 :脑出血患者血肿 的扩大与血压控制的程度相关 [16]。 他们研究了低分子肝素与弹力袜预防 DVT 的安全 本研究的选择标准也有可能影响到我们的数据 及结果。首先,我们只研究了接受 DVT 治疗的患 性,以及在脑出血患者中,其使用对血肿扩大有无 作用。他们发现用低分子肝素 (n=39) 和弹力袜 (n=36) 者。这种选择偏倚有可能将那些有早期血肿扩大可 预防 DVT/PE 与脑血肿扩大无关,但并没有说明研 究中 IVH 患者所占的比例,也没有说明入院后预防 能不会使用抗凝剂预防治疗。相反,我们只选择了 复查过 CT 的患者,这有可能忽略了那些接受抗凝 用药时间 ( 只提到在 48 小时后 )[6]。相比之下,我们 的研究对象中大部分是在出血 2-5 天开始使用抗凝 剂皮下注射并且病情稳定、所以没有复查 CT 的患者。 药,并且 28% (n=20) 是在入院 48 小时内。总的来 说,我们发现急性期 (2-4 天 ) 至亚急性期 (7 天 ) 使 能的严重脑出血患者排除在外,医生对这些患者可 因此本研究可能过多地反映了脑出血扩大者,因为 那些病情恶化的患者更有可能复查 CT。最后,只分 析治疗后第一次 CT 复查的血肿体积,我们就只能 用 DVT 预防药物皮下注射与血肿扩大无关。我们的 研究对象脑出血量从 0.5 mL 至 90 mL 不等。而在亚 研究迟发的血肿扩大。 急性期,有 2 例患者确实是有显著的血肿扩大,但 IVH 患者在急性期或亚急性期皮下注射低分子肝素 是没有发现与血肿扩大相关的特点或因素。以诊断 分类 ( 单纯 ICH 和 ICH+IVH) 及以有无脑室外引流 或普通肝素以预防 DVT 是安全的。关于脑出血患者 总之,我们的研究数据提示,对 ICH 和 ( 或 ) 皮下注射抗凝剂的安全性及有效性需要证实。 分类,均未见血肿增大。而 ICH 中 ICH+IVH 患者 的 Δvol 最小,说明脑室出血在血肿消退的过程中起 作用。在 36 例 ICH+IVH 患者中,有 21 例脑室外引 流,我们只发现 1 例有导管周围出血。因此,对脑 室外引流患者皮下注射抗凝剂可能是安全的,并发 症几率低。然而我们的数据的确显示,在急性期使 用抗凝剂者的 NIHSS 分值中位数较低 (4 天内为 9 分, 2 天内为 8.5 分 ),而在入院 7 天内使用者的 NIHSS 分值中位数为 11.5。这可能说明,在病情较重的患 42 参考文献 1. Adams HP Jr, del Zoppo G, Alberts MJ, Bhatt DL, Brass L, Furlan A, Grubb RL, Higashida RT, Jauch EC, Kidwell C, Lyden PD, Morgenstern LB, Qureshi AI, Rosenwasser RH, Scott PA, Wijdicks EF. Guidelines for the early management of adults with ischemic stroke: a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council, Clinical Cardiology Council, Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Council, and the Atherosclerotic Peripheral Vascular Disease and Quality of Care Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Groups: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2007;38:1655–1711. Wu et al DVT Prophylaxis Does Not Increase ICH Volume 2. Skaf E, Stein PD, Beemath A, Sanchez J, Bustamante MA, Olson RE. Venous 9. Dickman U, Voth E, Schicha H, Henze TH, Prange HW, Emrich D. Heparin thromboembolism in patients with ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke. Am J Car- therapy, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism after intracerebral diol. 2005;96:1731–1733. 3. Warlow C, Ogston D, Douglas AS. Deep venous thrombosis of legs after 4. hemorrhage. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 1988:1182–1183. 10. Kazui S, Naritomi H, Yamamoto H, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Enlargement strokes: Part I—incidence and predisposing factors. Part II—natural history. of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: incidence and time course. Stroke. BMJ. 1976;1178–1183. 1996;27:1783–1787. Ogata T, Yasaka M, Wakugawa Y, Inoue T, Ibayashi S, Okada Y. Deep venous 11. Lim JK, Hwang HS, Cho BM, Lee HK, Ahn SK, Oh SM, Choi SK. Multivari- thrombosis after acute intracerebral hemorrhage. J Neurol Sci. 2008;272:83– ate analysis of risk factors of hematoma expansion in spontaneous intracerebral 86. hemorrhage. Surg Neurol. 2008;69:40–45. 5. Broderick J, Connolly S, Feldmann E, Hanley D, Kase C, Krieger D, Mayberg 12. Huttner HB, Steiner T, Hartmann M, Ko¨hrmann M, Juettler E, Mueller M, Morgenstern L, Ogilvy CS, Vespa P, Zuccarello M. Guidelines for the S, Wikner J, Meyding-Lamade U, Schramm P, Schwab S, Schellinger PD. Management of Spontaneous Intracerebral Hemorrhage in Adults 2007 Update: Comparison of ABC/2 estimation technique to computer-assisted planimetric a guideline from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Associa- analysis in warfarin-related intracerebral parenchymal hemorrhage. Stroke. tion Stroke Council, High Blood Pressure Research Council, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes in Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Stroke. 2007;38:2001–2023. 6. Orken DN, Gulay Kenangil G, Ozkurt H, Guner C, Gundogdu L, Basak M, Forta H. Prevention of deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurologist. 2009;15:329 –331. 7. Kiphuth, IC, Staykov D, Kohrmann M, Struffert T, Ricter G, Bardutzky J Koll- 2006;37:404–408. 13. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666–670. 14. Brott T, Broderick J, Kothari R, Barsan W, Tomsick T, Sauerbeck L, Spilker J, Duldner J, Khoury J. Early hemorrhage growth in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 1997;28:1–5. mar R, Maurer M, Schellinger PD, Hilz MJ, Doerfler A, Schwab S, Huttner HB. 15. Lacut K, Bressollette L, Le Gal G, Etienne E, De Tinteniac A, Renault A, Rou- Early administration of low molecular weight heparin after spontaneous intrac- hard F, Besson G, Garcia JF, Mottier D, Oger E. Prevention of venous throm- erebral hemorrhage—a safety analysis. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27:146 –150. bosis in patients with acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2005;65:865– 8. Boeer A, Voth E, Henze TH, Prange HW. Early heparin therapy in patients with spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1991;54:466–467. 869. 16. Kazui SMK, Sawada T, Yamaguchi T. Predisposing factors to enlargement of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma. Stroke. 1997;28:2370–2375. 43