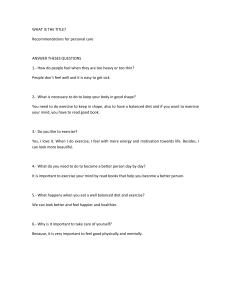

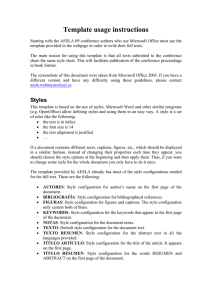

2022 19th International Joint Conference on Computer Science and Software Engineering (JCSSE) | 978-1-6654-8510-4/22/$31.00 ©2022 IEEE | DOI: 10.1109/JCSSE54890.2022.9836265 Understanding Relationships among Learning Styles, Learning Activities and Academic Performance: From a Computer Programming Course Perspective Phway Thant Thant Soe Lin Chutiporn Anutariya Piriya Utamachant Department of ICT Department of ICT Department of ICT School of Engineering and Technology School of Engineering and Technology School of Engineering and Technology Asian Institute of Technology Asian Institute of Technology Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) Pathumthani, Thailand Pathumthani, Thailand Pathumthani, Thailand [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Investigating factors that influence the learning process of students is important, especially in online education. It can help course instructors to design the learning environment that really fits the course requirements and students and to enhance the learning performance. This study focuses on identifying different learning styles and finding the relationships among learning styles, learning activities and performance of computer science students in a Java programming course. According to the results, students with balanced preference on receiving information obtained highest scores although most of them are visual learners in this aspect. It indicates that adding more visual presentations in teaching process will be helpful to enhance learning performance. As it is one of the very first programming courses, most students prefer to follow the instructors’ steps in solving the problems and obviously they joined the class more regularly than others. Therefore, concrete examples that involve well-defined procedures, facts, data, and experimentation are essential to teaching programming language. Moreover, the results confirmed that the number of assignment attempts and solving the in-class problems could considerably improve the achievement of the learning outcomes and also related to the understanding of the programming in a sequential manner. Consequently, students should be encouraged to do more assignments and practice problems in learning the programming through online. Index Terms—Computer Programming Course, Learning Styles, Learning Activities, Learning Performance, Learning Analytics I. I NTRODUCTION In recent years, pandemic has forced and accelerated the change of teaching and learning from traditional face-toface classroom to online and blended mode. Instructors apply e-learning platforms and Learning Management Systems (LMSs) to deliver course materials, assignments and other functionalities. With the help of LMSs, instructors can manage the delivery of course materials and track the students learning and performance easily. 978-1-6654-3831-5/21/$31.00 ©2022 IEEE During the design, development and delivery of an online course, it is challenging to offer the learning strategies and deliver the materials that can meet both course objectives and support students’ learning styles. Since different students may have different preferred learning styles, implying that they learn best when the learning environment matches their learning styles. Programming courses are essential components in engineering and computing related fields. More importantly, some students in programming courses face with difficulties since they consider the programming modules to be complex, problematic and difficult to learn [1]. Therefore, these difficulties can lead to high failure rate and dropout rates. It is also challenging to monitor learners’ genuine learning process and ever-changing learning behavior in computer programming education [2]. In the programming course perspective, some studies showed that learning styles influenced the performance but some could not find the significant effect. This gap gives a further investigation on students’ activities, assignments and class attendance in relation to the learning styles and performance since it can help the instructors understand the students and deliver teaching strategies effectively. This study analyzes the effect of each learning style dimension using Felder and Silverman Learning Style Model (FSLSM) and students’ class activities including assignments, in-class problems and attendance in relation to the performance of a Java programming course, supported by the Moodle LMS. This study has three main hypotheses. Hypothesis 1 (H1): Different learning styles have significant effect on the performance. Hypothesis 2 (H2): Learning activities are significantly related to the performance. Hypothesis 3 (H3): There is a significant relationship between learning styles and learning activities. The paper is organized as follow: Section 2 reviews related Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply. work, Section 3 presents the proposed framework, hypothesis development, experimental design and data collection, Section 4 explains the data analysis and results, and Section 5 discusses the results, concludes and recommends future research. II. R ELATED W ORK This section reviews related research on learning style identification, log data analysis and learning performance analysis in the e-learning platforms and LMS, especially in the computer programming education. Identifying learning styles of students can indicate how they learn in a course and the way they prefer to learn. It can help an instructor arrange teaching strategies and pedagogical materials and to optimize the interaction between teachers and students. There are several well-known learning style models that are used in the analysis of learning styles in education. The Kolb’s learning model was utilized to identify students’ learning styles and find the relationship with learning scores in programming language [3]. They found that different learning styles significantly influenced the learning performance [3]. Furthermore, understanding student learning styles can be used to support personalization e-learning. The study of [4, 5] applied FSLSM learning styles to customize learning materials and user interface, while the studies [1, 6] adopted the Visual, Auditory, Reading/writing and Kinesthetic (VARK) model to capture the predominant learning styles and arrange the pedagogical materials in programming courses accordingly. The study [7] recommended e-learning content based on student preferences and user behavior analysis by using Honey and Mumford model. Several research have suggested that a clear understanding in learners’ behavior and engagement is valuable in the design and development of education platforms. The paper [8] proposed a learning analytics process of investigating the relationships among structure and design of Thai Massive Open Online Course (MOOC), performance and engagement of the students. This study used assignment completion and quiz activities as learning engagement indicators. The results confirmed that learner’s engagement was different depending on different structures and learning objectives in MOOCs. Some studies used log data analysis as the parameter to track behavior of students in e-learning platforms. The study [9] examined the logs from the discussion forum of the online programming course and found that students who took a more active role in the activity stream did better in the course. The study thus suggested that students should be encouraged to participate actively in discussion forums to improve learning performance. Log data from LMSs has been utilized to predict and evaluate academic performance through machine learning techniques such as linear regression, logistic regression and Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT). The logs related to the discussion forum and exercises were significant factors for academic achievement in blended mode of education [10]. In the study of performance evaluation using students’ behavior data, the researchers used LMS logs related to discussion forums, resources, lessons, tests and assignments to predict students’ performance by using GBDT [11]. In addition, the logs from students’ learning actions related to course activities and materials were used to understand the learning process and types of learners [12]. The study found that students preferred lecture slides while working on programming assignments and students tried to seek help from forum only when they struggled [12]. III. P ROPOSED FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYZING LEARNING STYLES , LEARNING ACTIVITIES AND ACADEMIC PERFORMANCE This study investigates how learning styles and learning activities influence the learning outcomes or performance in a programming course. Moreover, learning activities of the course are expected to improve the learning performance. A. Study Framework This study identified different learning styles of the programming students by adopting the Felder and Silverman learning model with the use of Index of Learning Style (ILS) questionnaire [13]. The relationship among learning styles, learning activities and performance of the students was further analyzed. In general, the students who attend the class regularly and try to solve more assignments and problems should achieve better performance. Considering that, the learning activities of the online programming students was captured using their attendance, number of assignment attempts and problems solved in class. The framework of the study is outlined in Fig. 1. Fig. 1. Study Framework This study used three main factors including learning styles, learning activities and performance. The learning styles of the students were defined by ILS questionnaire developed on FSLSM. Attendance, assignment attempts and in-class problem solved collected from the LMS logs were used as indicators for learning activities. Finally, the summative learning performance and formative learning performance were used to measure the learning performance. The factors used in the study framework with selected features and measures are described in Table I. Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply. TABLE I I NDICATORS AND MEASURES FOR EACH FACTOR IN THE STUDY FRAMEWORK Factors Learning Styles (LS) Learning Activities (LA) Performance (P) Indicators Processing Perception Input Understanding Attendance Assignment attempts rate In-class problems solved Summative Learning Performance Formative Learning Performance FSLSM [13], which covers four dimensions: processing, perception, input and understanding, was selected to identify the learning styles of the programming students. Firstly, this model was invented for educational purposes and engineering students in particular. Additionally, it is suitable for educational studies that focus on Technology Enhanced Learning (TEL) [14]. Each learning style can be explained as follows: • Processing Dimension (Active/ Reflective/ Balanced): Some students may prefer “active” experimentation and group works. But some students feels more comfortable with “reflective” observation and better at individual works. Some students may have balanced preference in processing the information. • Perception Dimension (Sensing/ Intuitive/ Balanced): There may be some “sensory” students who desire to solve the problems by following the instructors’ guidance but “ intuitive” students come up with their own approach. Balanced ones prefer to follow instructors strategies and also try to innovate their solutions. • Input Dimension (Visual/ Verbal/ Balanced): Students can have different preferences in receiving the information during their learning process, visual or textual. “Visual” learners remember more easily with flow charts, diagrams, demonstrations and so on. “Verbal” learners prefer textual explanation to visual demonstrations. Balanced students are those who are comfortable with either visual presentation or verbal explanation. • Understanding Dimension (Sequential/ Global/ Balanced): In the understanding dimension, “sequential” students prefer to do step by step approach to understand everything but “global” learners try to capture the overall picture before studying the details. Some students do not have strong preference and they progress toward understanding depending on the situation. B. Development of Hypothesis Based on the framework of this experiment, three main hypotheses and sub-hypotheses about online programming language learning supported by Moodle LMS were developed: H1: Different learning styles have significant effect on the performance. H1a: Students with different learning styles have different summative performance (final scores). Measures Processing scores of active/ reflective/ balanced Perception scores of sensing/ intuitive/ balanced Input score of visual/ verbal/ balanced Understanding scores of sequential/ global/ balanced Online classroom attendance rate (percentage) Assignment attempts (percentage) Number of practice problems solved in the class Final score Assignment score H1b: Students with different learning styles have different formative performance (assignment scores). H2: Learning activities are significantly related to the performance. H2a: Learning activities are significantly correlated to the summative learning performance (final scores). H2b: Learning activities are significantly correlated to the formative learning performance (assignment scores). H3: There is a significant relationship between learning styles and learning activities. H3a: Students with different learning styles have significant differences with respect to the online classroom attendance rate. H3b: Students with different learning styles have significant differences with respect to the number of assignment attempts. H3c: Students with different learning styles have significant differences with respect to the number of in-class problems solved. C. Experimental Design and Data Collection This study collected data of a Java programming course, namely “Computer Programming Skill 2” which is a required course in an undergraduate computer science curriculum in a university in Thailand succeeding from a C programming course. Due to the COVID-19 lockdown, the course was conducted online using Zoom and Moodle LMS with the total of 150 enrolling students. The course was delivered with one lecture, three workshops and assignments per week for a 15week period. To identify the FSLSM learning styles of the students, ILS questionnaire was launched in Moodle, consisting of 44 forced questions, of which 11 are used to identify each dimension. There were 137 students answering the questionnaire, 41 students of which dropped out, and 96 students completed the course. Therefore, the learning styles, activity logs and the scores of these 96 students were used in this study. In addition, their attendance rate, number of assignment attempts and number of problems solved in the class were extracted from the Moodle LMS database to capture their learning activities. The attendance of the students was the rate (%) of attending the Zoom classroom. The assignment attempt is the percentage of the number of assignments they did during the 15 week-period. In-class problems solved is the the number of problems the student solved in the class. Finally, Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply. to measure the learners’ performance, their final scores were used to indicate the summative learning performance, and the assignment scores were used for the formative performance. IV. DATA A NALYSIS AND R ESULTS A. Learning Styles of the Students From the ILS questionnaire, the students were categorized according to their learning style preference. The score of the ILS questionnaire can be evaluated as follows: If the score on a scale is between 1 and 3, it indicates a mild/fair preference, and is considered as balanced student for that dimension. • If the score on a scale is between 5 and 7, it indicates a moderate preference for one dimension and the student will learn better in a teaching environment which favors his/her preference. • If the score on a scale is between 9 and 11, it indicates a strong preference for one dimension, and the student may encounter difficulties in the environments which do not favor his/her preference. • Fig. 2 depicts the learning style distribution of 96 students in each ILS dimensions. In processing dimension, most students had a balanced preference between active and reflective as shown in Fig. 2 (a), meaning that they are comfortable with either active experimentation or reflective observation in processing the information. Similarly, most students showed a fair preference in the way they approach to understanding in their learning process as shown in Fig. 2 (d). The number of sensing and balanced learners were almost equal and far exceeded that of intuitive in the perception dimension Fig. 2 (b). It can be considered that students would desire to solve the problems in standard methods rather than innovative way. According to the input dimension, there were less verbal students and most of the students are visual learners Fig. 2 (c). B. Learning Styles and Learning Performance (H1) To determine the significant effect of each learning style dimension on the performance, one way ANOVA was conducted for each dimension on the performance. A one-way ANOVA found a significant effect of input dimension (F (2, 93) = 5.63, p < 0.05) on final scores as described in Table II. The final scores in terms of the input dimension is shown in Fig. 3. A Tukey post-hoc test confirms the difference between visual and balanced (p < 0.05). Thus, the average exam score of the balanced learners s (M = 51.87, SD = 22.66) was significantly higher than visual learners (M = 34.76, SD = 24.59) in the input dimension. To determine the significant effect of each learning style on the assignment score, one-way ANOVA was conducted for each dimension. There was no statistically significant difference in mean assignment scores of the processing, perception, input and understanding dimensions. Fig. 2. Learning Styles of Students TABLE II S UMMARY OF THE HYPOTHESIS TESTING FOR LEARNING STYLES AND S UMMATIVE LEARNING PERFORMANCE (H1 A ) Dimension Processing Perception Input Understanding Learning Style Active Reflective Balanced Sensing Intuitive Balanced Visual Verbal Balanced Sequential Global Balanced Final Score n M 18 41.80 6 31.38 72 42.92 45 41.65 8 48.97 43 41.05 49 34.76 8 38.13 39 51.86 15 40.56 10 33.19 71 43.53 SD 24.91 27.72 25.16 27.36 24.17 22.90 24.59 26.83 22.66 24.74 21.05 25.78 ANOVA F = 0.58, p = 0.56 F = 0.34, p = 0.71 F = 5.63, p = 0.005* F = 0.77, p = 0.47 C. Learning Activities and Learning Performance (H2) Results of the Pearson correlation indicated that the final score and the number of assignment try were positively associated, r (94) = 0.48, p < 0.05. Similarly, solving the in-class problems was also positively correlated with the final score, r (94) = 0.29, p < 0.05. There was also a significant positive association between assignment scores and number of assignment try, r (94) = 0.88, p < 0.05. However, there was no significant relation between attendance and performance of the students. D. Learning Styles and Learning Activities (H3) To determine the significant effect of each learning style dimension on the attendance, one-way ANOVA was conducted Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply. TABLE III S UMMARY OF THE HYPOTHESIS TESTING FOR LEARNING STYLES AND ATTENDANCE (H3 A ) Dimension Learning Style Processing Perception Input Fig. 3. Distribution of final scores for the input dimension for each dimension. A one-way ANOVA found a significant effect of perception dimension on attendance (F (2, 93) = 5.22, p < 0.05) as described in Table III. A Tukey post-hoc test confirms the significant difference between intuitive and sensing at p < 0.05 and marginally difference between balanced and intuitive learners at p = 0.05. Therefore, it can be considered that the attendance of intuitive learners (M = 81.11, SD = 11.58) was significantly lower than that of sensing (M = 92.64, SD = 6.58) and balanced learners (M = 89.66, SD = 11.47). The attendance distribution related to the perception dimension is shown in Fig. 4. The test failed to find any significance of processing, input and understanding dimensions related to the attendance. There was no statistically significant difference in the number of assignment attempt according to different learning styles of the students. A one-way ANOVA demonstrated that only the understanding dimension had significant effect on the problems solved in the class (F (2, 93) = 4.58, p < 0.05) as stated in Table IV. A Tukey post-hoc test confirms the difference between sequential and balanced (p < 0.05). It can be considered that the sequential learners solved more in-class problems (M = 17.98, SD = 5.7) than balanced learners (M = 12.17, SD = 7.532) in the understanding perspective. The distribution of the in-class problems solved related to the understanding dimension is shown in Fig. 5. Understanding Active Reflective Balanced Sensing Intuitive Balanced Visual Verbal Balanced Sequential Global Balanced Attendance n M 18 86.91 6 92.59 72 91.02 45 92.64 8 81.11 43 89.66 49 91.06 8 94.17 39 90.66 15 92.44 10 88.22 71 90.20 SD 14.46 3.89 8.73 6.58 11.58 11.47 8.03 2.89 8.94 6.39 14.56 9.80 ANOVA F = 1.41, p = 0.24 F = 5.21, p = 0.007* F = 0.62, p = 0.54 F = 0.57, p = 0.57 TABLE IV S UMMARY OF THE HYPOTHESIS TESTING FOR LEARNING STYLES AND IN - CLASS PROBLEM SOLVED (H3 C ) Dimension Learning Style Processing Perception Input Understanding Active Reflective Balanced Sensing Intuitive Balanced Visual Verbal Balanced Sequential Global Balanced In-class Problems Solved n M SD 18 10.09 6.20 6 13.37 7.41 72 14.41 8.20 45 13.55 7.36 8 10.12 8.99 43 14.22 8.33 49 12.84 7.96 8 14.00 7.11 39 14.38 8.15 15 17.98 5.70 10 16.81 10.61 71 12.17 7.53 ANOVA F = 2.22, p = 0.11 F = 0.90, p = 0.41 F = 0.42, p = 0.66 F = 4.58, p = 0.01* V. D ISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION This study sought to experimentally test the relationships among learning styles, learning activities, and learning performance of a programming course and significant results from the hypothesis testing are summarized in Table V. Based on the results of ILS questionnaire, most students were likely to follow the instructors in problem solving. Therefore, the inclass instructions and lectures can be very helpful to enhance Fig. 4. Attendance in terms of perception dimension Fig. 5. In-class problems solved in terms of understanding dimension Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply. TABLE V S UMMARY OF THE SIGNIFICANT HYPOTHESIS TESTING RESULTS Significant Results H1a: Students with different learning styles (input dimension) have different summative performance. H2a: Learning activities (assignment attempts and in-class problems solved) are significantly correlated to the summative learning performance. H2b: Learning activities (assignment attempts) are significantly correlated to the formative learning performance. H3a: Students with different learning styles (perception dimension) have significant differences with respect to the online attendance rate. H3c: Students with different learning styles (understanding dimension) have significant differences with respect to the number of in-class problems solved. their study. Similarly in receiving the information, students also showed strong preference on the visual presentations rather than textual explanations. In relation to the performance, however, this study points out that the students with a balanced preference on the input dimension got higher scores and other personal preferences do not influence their learning outcomes according to H1. That is, the performance of visual learners was lower than that of balanced students. Moreover, the performance of the verbal students was slightly higher than visuals despite the less number of verbal students on that dimension. A possible reason could be related with understanding a long textual questions, especially in “Class Programming”. Visual learners are those who learn best by visual demonstrations, and they are not good at textual description. On the other hand, verbal and balanced students can be benefited from these kind of works. The results of H2 showed that the more the students tried the assignments and in-class problems, the better the performance they established. Following H3, students who have tendency for sensing join the class more regularly and sequential learners tried to solved the problems more than others. Therefore, the course instructors should provide concrete examples that involve well-defined procedures, facts, data, and experimentation and problem solving to better motivate the students. In summary, this study confirms that practicing more inclass problems and working on assignments play an important role in enhancing the understanding and performance in programming language learning. Since a majority of students prefer to follow the instructions of the instructors, clear and understandable instructions with more visual presentations should be delivered to support them to learn better. However, due to the small sizes in some learning style preferences, the study could not confirm several interesting relationships and findings. Future research involves further investigation in the coding process, coding patterns, code quality and common mistakes in relation to the learning styles and learning performance. R EFERENCES [1] D. Kezang, “Understanding students’ C programming language learning styles: A case study in College of Science and Technology,” Journal of Information Engineering and Applications, vol. 11, January 2021. [2] D. Song, H. Hong and E. Oh, “Applying computational analysis of novice learners’ computer programming patterns to reveal self-regulated learning, computational thinking, and learning performance,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 120, 2021. [3] R. S. Shaw, “A study of the relationships among learning styles, participation types, and performance in programming language learning supported by online forums,” Computers & Education, vol. 58, 2012, pp. 111-120. [4] S. V. Kolekar, R. M. Pai and M. M. Pai, “Adaptive user interface for Moodle based e-learning system using learning styles,” Procedia Computer Science, vol. 135, 2018, pp. 606-615. [5] B. Ciloglugil, “Adaptivity based on Felder-Silverman Learning Styles Model in e-Learning systems,” 4th International Symposium on Innovative Technologies in Engineering and Science, vol. 3, November 2016. [6] F. Diaz, T. P. Rubilar, C.C.Figueroa and R.M. Silva, “An adaptive eLearning platform with VARK learning styles to support the learning of object orientation,” 2018 IEEE World Engineering Education Conference (EDUNINE), March 2018, pp. 1-6. [7] A. F. Baharudin, N. A. Sahabudin and A. Kamaludin, “Behavioral tracking in e-Learning by using learning styles approach,” Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, vol. 8, October 2017, pp 17-26. [8] C. Anutariya and W. Thongsuntia, “MOOC design and learners engagement analysis: A learning analytics approach,” 2019 International Conference on Sustainable Information Engineering and Technology (SIET), 2019, pp. 5-10. [9] A. Carter, C. D. Hundhausen and O. Adesope, “Blending measures of programming and social behavior into predictive models of student achievement in early computing courses,” Association for Computing Machinery, vol. 17, September 2017. [10] I. Mwalumbwe and J. S. Mtebe, “Using Learning analytics to predict students’ performance in Moodle Learning Management System: A Case of Mbeya University of Science and Technology,” The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, vol. 79, March 2017, pp. 1-13. [11] H. Wan, Q. Yu, J. Ding and K. Liu, “Students’ behavior analysis under the Sakai LMS,” 2017 IEEE 6th International Conference on Teaching, Assessment, and Learning for Engineering, pp. 250-255, December 2017. [12] S. L. Pernas, Saqr, M. and O. Viberg, “Putting it all together: Combining learning analytics methods and data sources to understand students’ approaches to learning programming,” Sustainability, vol. 13, 2021. [13] R. M. Felder and L. K. Silverman, “Learning styles and teaching styles in engineering education,” Engineering Education, vol. 78, 1988, pp. 674-681. [14] A. Al-Azawei, A. Al-Bermani, and K. Lundqvist, “Evaluating the effect of Arabic engineering students’ learning styles in blended programming courses,” Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, vol. 15, 2016, pp.109- 130. Authorized licensed use limited to: UNIVERSIDAD VERACRUZANA. Downloaded on February 22,2025 at 00:19:08 UTC from IEEE Xplore. Restrictions apply.