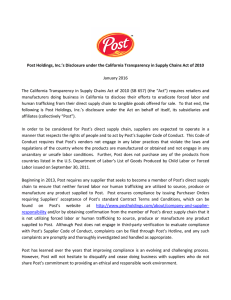

Int. J. Sustainable Strategic Management, Vol. 7, Nos. 1/2, 2019 91 Green supply chain management: impact on environmental performance and firm competitiveness Cheng Ling Tan* Graduate School Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia Email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Suhaiza Hanim Mohd. Zailani Faculty of Business and Accountancy, Universiti Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Sieow Chin Tan Graduate School Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia, 11800 Penang, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Sook Fern Yeo Faculty of Business, Multimedia University, 75450, Bukit Beruang, Melaka, Malaysia Email: [email protected] Abstract: Unrestrained industrialisation resulting in environmental pollution has mobilised the unstinting endeavours of scientist, researchers, policy makers and ecologist in a quest to rapidly unearth solutions to mitigate further environmental deterioration. One promising ongoing development is green supply chain management (GSCM), which promises a reduction of pollution and waste in manufacturing. GSCM achieves this through the mechanism of improving manufacturing efficiency, by reducing costs, enhancing product quality and improving product delivery. This study applies the natural resource-based view, and quantitatively examines the impact of the implementation of GSCM on firm environmental performance, and firm competitiveness. Data was collected from 122 sampled firms, analysed, and evaluated in two ways. Firstly, using partial least squared-structured equation modelling (PLS-SEM), results indicate that ‘green procurement’, and ‘green supplier and customer collaboration’, have a significant positive relationship with both firm environmental performance, and, firm competitiveness. Secondly, using importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA), both ‘green Copyright © 2019 Inderscience Enterprises Ltd. 92 C.L. Tan et al. procurement’ and ‘green supplier and customer collaboration’ are mapped in the high in importance/high-performance quadrant. The practical recommendations are for organisations to prioritise efforts and resources towards ‘green procurement’ and ‘green supplier and customer collaboration’ in order to maximise the return on ‘green’ investment. Keywords: green supply chain management; GSCM; green procurement; green production; firm environmental performance; firm competitiveness; manufacturing firm; supplier; customer; collaboration. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Tan, C.L., Zailani, S.H.M., Tan, S.C. and Yeo, S.F. (2019) ‘Green supply chain management: impact on environmental performance and firm competitiveness’, Int. J. Sustainable Strategic Management, Vol. 7, Nos. 1/2, pp.91–112. Biographical notes: Cheng Ling Tan is Associate Professor and Deputy Dean of the Graduate School of Business at the University of Sains Malaysia. She lectures on operations strategies alongside supervisory MBA, DBA, and PhD students in the fields of management, innovation, operations management, supply chain management, and quality management. Her research accomplishment has been noted in many international referred journals, research grants, and training and consultancy. She has served as a peer reviewer for numerous international publications. Suhaiza Hanim Mohd. Zailani is a Professor of Supply Chain at the Faculty of Business and Accountancy, University Malaya. Her research interest is mainly on the development of three key areas: quality management, supply chain management and Halal issues. Her achievement in supply chain management is excellence as evident in number and quantum of publications, research grants, consultations, training, industrial linkages, and professional appointments that she has successfully secured and fulfilled. Her expertise has also been recognised within the academia as she has been appointed as the editorial board members for almost 50 international referred journals and conferences. Sieow Chin Tan is an MBA graduate from Graduate School of Business, Universiti Sains Malaysia. She is currently working with a multi-national company at Free Trade Zone, Bayan Lepas at Penang. Her main research interest is in the field of supply chain management, particularly in green supply chain. Sook Fern Yeo is a Lecturer at the Faculty of Business, Multimedia University in Melaka. She commenced career as a lecturer with 16 years of teaching experience. She teaches marketing for bachelor degree programs, specifically understanding management, fundamentals of marketing, service marketing, brand management and strategic marketing. She supervises undergraduate students mainly in marketing, human resource, and international business. She also published in internationally refereed conference papers, journal articles, and book chapters. 1 Introduction In the intensively competitive world, the competition exists not only between organisations but also among the supply chains. In recent years, the rapid technological development and modern transportation system have made the entire supply chain of an Green supply chain management 93 organisation to be more effective and efficient. Therefore, supply chain management (SCM) plays a very critical role as a key factor to improve organisational performance and to gain a competitive advantage (White and Mohdzain, 2009). Excellence in SCM dictates the significant aspect of customer satisfaction, operating performance and many other key performance indicators of the companies that determine the competitiveness of a company. However, to win more businesses,many companies are demanding the suppliers to implement green supply chain management (GSCM) practices and comply with additional environmental requirements (Lee et al., 2012). The increasing pressure of the environmental issue caused by the industrial activities has also urged many companies to establish environmental key performance indicators. With the close monitoring on the environmental performance, the companies will be able to produce better goods and deliver the better services at a lower cost compared to others which are operating in the same economic context and hence increase the firm competitiveness (Testa and Iraldo, 2010). Many studies recommended that companies shall implement GSCM in order to become more environmental accountable (Ciliberti et al., 2008) as well as to improve the firm environmental performance and its competitiveness (Hervani et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2018). The companies apply the green practices in their supply chain ranging from green purchasing, green production (GP), reverse logistic, supplier and customer collaboration to investment recovery (Zhu and Sarkis, 2006). Practically, the companies implementing GSCM will incorporate the green purchasing of environmentally-friendly materials as well as incorporating the 3R (reduction, reuse, and recycling) in the procurement policy. The usage of environmentally-friendly materials will ensure the environmentally-friendly processes in the production (Ninlawan et al., 2009; Ramakrishnan et al., 2015). Reverse logistics is one of the GSCM practices that commonly adopted among the companies to retrieve the products from end users such as packaging cases for re-use and redistribution (Ninlawan et al., 2009). The companies believe that through the efforts in recycling and reuse will derive greater value from materials and products as well as reduce inventory and waste, and hence bring the investment recovery in long-term (Zhu et al., 2005, 2008). Many researchers revealed that GSCM practices will help the manufacturing companies reduce cost and increase productivity, resulting in the firm’s ability to differentiate itself from others, thereby achieving better environmental and financial performance and secure more competitive advantage, resulting in higher firm competitiveness (Lopez-Gamero et al., 2009; Tan et al., 2016). The companies that are proactive in environmental issue may boost company’s environmental performances and at the same time, help to increase firm competitiveness (Lefebvre et al., 2003). Therefore, competitive forces make going green an inevitable course, where companies either comply voluntary or abide by environmental regulatory enforcement (Burke and Gaughran, 2005). Despite many manufacturing companies aware that GSCM as a tool for waste elimination, cost-efficiency, and at the same time environmentally friendly (Ninlawan et al., 2009), the implementation of GSCM practices in Malaysia is still slow. This reflects that there may be still many issues in the GSCM implementation at the aggregate level of the manufacturing companies which has hindered the overall initiatives of the manufacturing companies to implement it. Given the importance of the green practices on the companies’ environmentally-friendly image and firm competitiveness, this paper focuses the study of the impact of GSCM on firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness. 94 C.L. Tan et al. 2 Literature review 2.1 Green supply chain management Today, businesses are progressing towards sustainable solutions (Menzel et al., 2010) and are obliged to adopt the three bottom lines, that is, the 3P-people, profit and planet (Tan and Zailani, 2009) in order to achieve lasting success. Many environmentally-responsible companies implement sustainability practices through the adoption of GSCM (Mohan Kumar et al., 2017; Menzel et al., 2010). GSCM practices are internal and external environmental management system that encompass investment recovery, green purchasing, GP and green distribution or marketing, investment recovery, and reverse logistics in the SCM (Hervani et al., 2005; Menzel et al., 2010; Ninlawan et al., 2009; Rao and Holt, 2005). It is viewed as a form of environmental innovation (Zhu et al., 2010). The scope of GSCM practices covers the flow of material from the supplier, entire manufacturing process as well as the outbound logistics such as marketing and labelling. GSCM is not discretionary (Handfield et al., 1997) but are needed to mitigate the negative impact of industrialisation on the environment (Eltayeb et al., 2010a). Most of the companies implement GSCM practices to restrain business activities that have a negative impact on the natural environment (Tan et al., 2017; Gilbert, 2000). The initial cost invested in GSCM can be very expensive, however, it can be offset by operating efficiency, waste and energy reduction, improved quality, as well as less rework and reject quantity in the long run (Shen, 2010). GSCM practices help to improve the firm’s environmental performance and financial performance (Yang et al., 2010; Rao and Holt, 2005) and contributed directly to the firm’s competitiveness. Table 1 SCOR model versus GreenSCOR model SCOR GreenSCOR Plan Included processes of the plan, schedule and coordinated in supply chain activities. Collaboration with suppliers or customers on environmental issues. Source Associated with the procurement of materials and services to fulfil requested demand. Select supplier certified with environmental management system (EMS). Made Covered processes of transforming input into the output to meet requested demand. Minimising material usage. Deliver Associated with the processes of storing, packing and delivering products and services. Design route for minimising fuel consumption. Return Associated with processes of delivering and receiving from customer and suppliers, including the return of products, and commonly called as reverse logistic. Take back for reuse/recycle. Source: Adopted from Supply Chain Council (2010) Green supply chain management 95 In this study, three GSCM practices are selected namely green purchasing, GP, and green supplier and consumer collaboration, which are derived from the GreenSCOR model. GreenSCOR is a modified version of the existing SCOR model and includes the environmental process, as well as the process’s metric and performance. GreenSCOR explained five key supply chain environmental processes, namely Plan, source, make, deliver, return, which has been presented in Table 1 (Supply Chain Council, 2010). 2.2 Environmental performance A significant and growing of study has attempted to examine the highly sought area of environmental performance. In recent years, the firm’s environmental performance concept has been used in several studies (Poser et al., 2012). Definitions of the environmental performance concept are elaborated next. Environmental impacts caused by the company’s operations covering operations management and inputs and outputs, as well as strategic dimensions for managing stakeholder expectations (Poser et al., 2012). On the other hand, environmental performance is also defined as the corporation activity on environment impact (Sharma and Vredenburg, 1998). Besides, environmental performance has been defined as the extent of environmental activities taken by a company to mitigate environmental impacts (Schultze and Trommer, 2012). Based on Chien and Shih (2007), management performance and operational management consist of environmental aspect whereby management performance covers a wide range of measurement such as environmental policies, certification of the environmental system, community social responsibility as well as the company image. The previous study indicated that better environmental performance assured legal compliance and material efficiency (Zorpas, 2010). An investigation by Nawrocka and Parker (2009) had stressed on a more comprehensive evaluation of an organisational success should take into the considerations of the compliance on environmental policies and standards, certification of the environmental system, waste reduction strategies, cost-saving technologies as well as a systematic operational practice. In enhancing the study in environmental performance, previous studies also look into the firm’s community social responsibility, company image and material efficiency (Chien and Shih, 2007; Zorpas, 2010). Conversely, Freedman and Janggi (1992) and Levy (1995) indicated that there were firms with good environmental practices were not viewed positively by the market. There was a negative relationship between good environmental and economic in a short term. Similar finding found on reduction in toxic emission is not positively influenced on firm economic performance (Iraldo et al., 2009). Nawrocka and Parker (2009) stated that investing in environmental management seems to be the extra burden if the firm’s focus is cost instead of quality. By looking into short-term profit, the environmental investment may not attractive due to weak market response. Nevertheless, technological investment in terms of environmental innovation is capable to develop new technology and solutions which will reduce operating cost (Testa and Iraldo, 2010). Environmental performance affects economic performance in terms of cost (Rao and Holt, 2005). Waste reduction, used material reduction in production will increase efficiency followed by reduced operation cost despite better utilisation of natural resources. Greening inbounds lead to cleaner manufacturing and significantly outbound function as well as competitive and economic performance (Rao and Holt, 2005). Green adoption leads to increased sales, revenue and new market opportunities. Business activities with minimum negative impact on the natural environment will displace 96 C.L. Tan et al. competitors who fail to establish good environmental management. Additionally, environmental practices manage to cut cost along the firm’s supply chain through a series of internal practices such as inventory management, efficient resources consumption, cost reduction in waste treatment and discharge and to avoid the risk of penalty for non-compliances as well as cases of environmental accident (Chien and Shih, 2007; Singh et al., 2008). Greening any phase of supply chain potential to turn into economic and financial performance (Rao and Holt, 2005). In the pursing of economic outcome, the firm should consider the environmental burden and try to minimise the impact on the planet where a human being is dependent on it. Social justice has to be taken into account simultaneously in achieving balance deployment between environmental and economic return (Chien and Shih, 2007). On the other hand, the direct impact of environmental practices on financial and marketing performance is negative; however, it positively affects financial and marketing performance in the long term (Yang et al., 2010). Therefore, measures of firm environmental performance are included in the final research model. 2.3 Firm competitiveness The traditional definition of firm competitiveness is the competitive advantage of the firm against competitors in delivering goods and services effectively and efficiently in response to market demands (Bendavid-Val and Perine, 2003). The previous paradigm of firm performance was the primacy of concern of internal firm operations and cost differentiation with less attention given to upstream and downstream operations (Porter, 1990). Recent developments in environmental sustainability as part of CSR (Choi et al., 2017) have expanded the need for green initiatives as part of the success criteria of firms (Burke and Gaughran, 2005). The view today has since evolved to include the upstream deliverables and downstream dependency vertical aspects of the value chain in any consideration of firm competitiveness in relation to environmental sustainability (Testa and Iraldo, 2010). A research study by Rao and Holt (2005) define firm competitiveness in the context of GSCM as the successful minimisation of waste and the achievement of cost savings. The primary benefits of high firm competitiveness in GSCM is the promotion of synergy and efficiency within organisations and with business partners, with secondary benefits of enhanced corporate image, competitive advantage and marketing exposure (Rao and Holt, 2005; Chien and Shih, 2007). This outlook is backed by empirical studies of firms (Rao and Holt, 2005; Chien and Shih, 2007; Nawrocka and Parker, 2009; Tan and Zailani, 2009) which have demonstrated the conclusive linkage of firm effectiveness with various measures of firm performance. Focusing specifically on measures of firm competitiveness, Rao and Holt (2005) propose that effective criteria involve measurements of quality improvement, improved efficiency, productivity improvement, and cost saving. Contemporary empirical GSCM research literature (Vachon and Klassen, 2008; Li et al., 2004; Singh et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2010) concurs broadly with Rao and Holt (2005) with regards to the utilisation of the three key measures of price/cost, quality and delivery as measures of firm competitiveness. Given the wide consensus in published studies, the proposition of firm competitiveness as defined by the three dimensions (delivery, cost, and quality) is, therefore, a valid part of the research model. Green supply chain management 3 97 Underlying theory: natural resource-based view Since the environmental competitiveness has turned to be very important in doing business, the natural resources-based view (NRBV), developed from its original theory, Resource-based View (Vachon and Klassen, 2008) is well-fit to explain the research framework of this study. On top of the firm major resources argued by Grant (1991) in RBV namely, financial and economic resources, physical resources, human resources (people), technical resources (i.e., innovation capabilities), and intangible resources (business goodwill) (Testa and Iraldo, 2010), NRBV added natural environment (external environmental) as the firm valuable resource which will makes firm to be competitive. NRBV explained that the combination of resources from both internal and external in the supply chain creates higher organisational capabilities to fulfil customers’ expectations (Vachon and Klassen, 2008). Hence, a firm that has excellent internal resources and external resource in the entire supply chain (involving suppliers and customers) will contribute to better firm’s performance and competitiveness (Steinle and Schiele, 2008). The source of firm competitiveness should not be limited to internal resources capabilities but also from the external environment. Collaborative relationship of both internal resources with external environment accentuates the development of new technology and new competencies (Eltayeb et al., 2010). Based on the NRBV argument, GSCM which covers both components of internal and external resources can help the companies to overcome uncertainty and complexity (Zhu et al., 2006), and then lead to the better environmental performance and firm competitiveness. 4 Research framework and hypotheses development 4.1 Green purchasing and firm environmental performance Green purchasing is the activities that include the 3Rs (reduction, reuse, and recycling) of materials in the procurement process (Ninlawan et al., 2009). Green purchasing strategies comprise of a large part of inbound logistics and it is the environmental control at the upstream supply chain which involves the suppliers (Rao and Holt, 2005). These suppliers are usually required to ensure materials supplied are environmentally-friendly and produced in environmentally-friendly processes. Sometimes, the green purchasing activities may include providing design specification to the supplier, holding seminars, audit on supplier’s internal environmental management. Companies that emphasise in green purchasing will help to increase the firm environmental performance. Hence, our next hypothesis is as follows: Hypothesis 1 (H1) Green purchasing will positively influence firm environmental performance. 4.2 GP and firm environmental performance GP is the greening of the production phase or the internal supply chain. It emphasises operation efficiency, particularly minimise the impact of production on the environmental (Tan et al., 2002). GP can be operationalised through eight variables, that is, environmentally-friendly raw materials, substitution or replacement of materials, 98 C.L. Tan et al. environmentally-friendly design, environmental concern, minimisation of waste emission, cleaner process and recycling in production stage (Rao and Holt, 2005). Companies that practice GP are highly efficient in its production process as it generates a very little environmental impact (Ninlawan et al., 2009). It also helps to reduce production waste and pollution to various streams (Menzel et al., 2010). Based on the preceding information, it is posited that: Hypothesis 2 (H2) GP will positively influence firm environmental performance. 4.3 Green supplier and customer collaboration Green supplier and customer collaboration involve an organisation with its suppliers and customers for environmental management and solution. The general collaboration includes joint venture (Vachon and Klassen, 2008), customer support and education (Rao, 2004). Suppliers support includes providing direct onsite technical support, financial assistance to help supplier, education activities such as holding seminars, creating awareness and sharing on the know-how knowledge with the supplier, or joint ventures that enable the long-term collaborative relationship to develop cleaner technology. Similarly, customers are given the opportunity to attend educational activities, seminars and sharing sessions that enable them to appreciate environmental friendly practices in production and eventually increase the environmental performance of the company. Therefore, the following hypothesis is offered. Hypothesis 3 (H3) Green supplier and consumer collaboration will positively influence firm environmental performance. 4.4 Firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness Business performance serves as the fundamental purpose for external reporting and internal business control and analysis (Hervani et al., 2005) for continuous improvement. In a supply chain where multiple vendors, suppliers, customers, retailers and manufacturers involved, the activities carried out at each party has contributed to environmental impact significantly. Accumulated of these environmental impacts may affect the firm environmental performance which will later jeopardise the firm image and then affect the firm competitiveness in business. In the study of environmental policy standards, Nawrocka and Parker (2009) expanded on the positive influence of firm environmental performance activities on firm competitiveness and have found the factors to correlate. This finding has been bolstered by a recent study (Yu et al., 2017) demonstrating a clear relationship with environmental performance. Therefore, it is important to understand the influence of the firm environmental performance on the firm competitiveness (Hervani et al., 2005). Due to the firm competitiveness comprises of three dimensions namely firm competitiveness in delivery, price and quality, the subsequent section will discuss the hypotheses development accordingly. 4.5 Firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness in delivery In the manufacturing context, the customer is looking for responsiveness and flexible services to be incorporating in the supply chain to improve the delivery. The direct effects of good environmental management increase the manufacturing firm’s operational Green supply chain management 99 optimisation and efficiency as well as improve its delivery in the entire supply chain (Bendavid-Val and Perine, 2003). Manufacturing firm operated in a sustainable context will generate sustainable profit and then increase its competitiveness. Based on the above discussion, the hypothesis is developed: Hypothesis 4 (H4) Firm environmental performance positively influences firm competitiveness in delivery. 4.6 Firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness in price Manufacturing firm’s operation interacts with the natural environment in term of energy consumption and waste management will contribute to the saving of production cost and production efficiency. The cost saving will be transferred to the customer thereby increasing a firm’s competitiveness in the marketplace. Cost saving from manufacturing cost able to reduce end product cost and offer the products at a more competitive price besides the increased profitability. Based on the preceding discussion, it is posited that: Hypothesis 5 (H5) Firm environmental performance positively influences firm competitiveness in price. 4.7 Firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness in quality Any negative environmental impact affects the liability of the firm at the overall level. Therefore, manufacturing firm adopted environmental management to reduce the risk exposure to environmental liabilities such as fine and accident happen due to improper environmental management. Environmental management is closely related to product quality and safety as well as worker healthiness and safety. The manufacturing companies have proper environmental management will improve its product quality. The high product quality perceived by the customer will increase the firm competitiveness in the market. Thus, the next hypothesis is formulated as below: Hypothesis 6 (H6) Firm environmental performance positively influences firm competitiveness in quality. 5 Research design 5.1 Sample A total of 541 firms with ISO 14001 certification had been selected purposively through the Malaysian Federation of Manufacturer (FMM) Directory Year 2010 and Malaysian Certified Online Database. Of the 541 ISO 14001certified firms, 10 firms that are located in Penang were selected for the pilot survey and the remaining 531 firms were used as samples for this study. The unit of analysis is the firms with ISO 14001 certification. The respondents acting on behalf are administrators working in the Environment, Health and Safety Department, that is, those holding a managerial or administrative position in operational, quality, production supply chain and engineering department. 100 C.L. Tan et al. 5.2 Instrument GSCM practices were measured by three subscales, that is, green purchasing [six items, adopted from Eltayeb et al. (2010b)], GP (four items, adopted from Zhu and Sarkis, 2004), green supplier and customer collaboration (seven items adopted from Zhu and Sarkis, 2004). Firm environmental performance is measured by seven items proposed by Zhu and Sarkis (2004). Firm competitiveness is assessed using a total of 14 items of instrument proposed by Li et al. (2004), where firm competitiveness in price has five items; firm competitiveness in quality has five items, and firm competitiveness in delivery has four items (see Appendix). 5.3 Data collection process Self-administered questionnaires were distributed to the samples through the human resources (HR) managers. In the cover letter, researchers requested the HR managers to distribute the questionnaires to the right respondent who may hold the senior manager position in operations/supply chain or factory manager. The follow-up calls made to the respective HR managers after two weeks to remind them of the collection of the questionnaire from the respondents. After the collection of the questionnaire, the HR manager returned the questionnaire using the provided envelopes with stamps. Of the 531 questionnaires distributed, 131 questionnaires were returned, but only 122 were found usable, which resulting a response rate of 23.6%. 5.4 Respondents’ profile The participating manufacturing companies were mainly from Penang (38.5%), Selangor (25.4%), Johor (9.0%), Perak (7.4%), Kuala Lumpur (5.7%), Melaka (4.9%), Kedah (4.1%), Negeri Sembilan and Sarawak (2.5%). Half of the responding manufacturing companies are from the electronic/electrical industry (50.8%), followed by basic metal, metals product and machinery(18%), rubber and plastics (9.0%), others (7.4%), chemical (5.7%), infrastructure/construction (2.5%), textile and wearing apparels (1.6%), wood-based products /furniture (1.6%) and food and beverages (0.8%). With regard to the ownership status of the companies, 69% of the companies are 100% foreign owned companies, followed by 100% local owned companies (25%), and the remaining 6% was joint venture companies. Among 122 participating companies, 101 were large firm size with the employee number more than 150; while 49 were small and medium firm size with the employee number less than 150. 6 Data analyses To rule out the influence of common method bias, Harmon’s single factor analysis was carried out. Unrotated factor analysis reveals the presence of ten factors with a total variance of 73.791%, and the first factor contributes 29.563% of the variance. Apart from that, care was taken during the construction of the instrument and also the data collection process. A two-stage analytical procedure (Anderson and Gerbing, 1988; Hair et al., 2014; Ramayah et al., 2016) involving SmartPLS 3.0 software (Ringle et al., 2015) was utilised to test the hypotheses. Green supply chain management 101 6.1 Measurement model The first step in PLS-SEM analysis is to evaluate the measurement model in order to determine how well the items load on the hypothetical construct. This involves examining the reliabilities of the indicators, the latent variables, internal consistency (composite reliability), and construct validity (loadings and average variance extracted) as well as discriminant validity (Fornell-Larcker criterion and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio). Table 2 reveals that the measurement model has adequate construct validity as suggested by Hair et al. (2010). Table 2 Variance inflation factor, loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted Construct Items VIF Loadings Composite reliability Average variance extracted Firm competitiveness in delivery (FCD) FCD1 1.382 0.753 0.866 0.619 FCD2 2.436 0.876 FCD3 1.863 0.724 FCD4 1.563 0.786 FCP1 3.446 0.893 0.909 0.669 FCP2 2.035 0.742 FCP3 2.979 0.893 FCP4 2.374 0.82 FCP5 2.137 0.725 0.885 0.607 0.918 0.615 0.895 0.684 Firm competitiveness in price (FCP) Firm competitiveness in quality (FCQ) Firm environmental performance (FEP) Green purchasing (GP) FCQ1 1.436 0.715 FCQ2 2.332 0.849 FCQ3 2.167 0.754 FCQ4 2.217 0.826 FCQ5 1.614 0.745 FEP1 2.033 0.686 FEP2 3.215 0.838 FEP3 2.525 0.789 FEP4 2.148 0.795 FEP5 2.201 0.785 FEP6 2.040 0.757 FEP7 2.383 0.828 GP1 2.246 0.911 GP2 2.615 0.899 GP3 1.835 0.771 GP4 1.908 0.709 Note: *AVE = average variance extracted. 102 C.L. Tan et al. Table 2 Variance inflation factor, loadings, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (continued) Loadings Composite reliability Average variance extracted 2.665 0.862 0.905 0.614 1.882 0.777 0.842 0.517 Construct Items Green production (GPR) GPR1 GPR2 GPR3 1.519 0.681 GPR4 1.723 0.742 GPR5 3.239 0.869 GPR6 2.037 0.754 Green supplier and customer collaboration (GSCC) VIF GSCC3 1.577 0.744 GSCC4 1.277 0.692 GSCC5 1.809 0.623 GSCC6 2.365 0.74 GSCC7 1.780 0.785 Note: *AVE = average variance extracted. Two items (GSCMSC1, loading = 0.449, and GSCMSC2, loading = 0.609) and two items of GP (GP5, loading = 0.420, and GP6, loading = 0.451) were deleted were deleted due to undesirable loadings and low AVE. The loadings of all other items were satisfactory (that is, between 0.686 and 0.911). Composite reliability of all constructs ranges from 0.866 to 0.918, while the AVE for all constructs is between 0.517 and 0.684. The variance inflation factors (VIF) for all items are below 0.5, that is, ranging from 1.381 to 3.239, showing that there is no serious multicollinearity issue. 6.2 Discriminant validity Assessment of discriminant validity is needed to prevent multicollinearity issues. Both the Fornell and Larcker criterion and the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) are used to determine the discriminant validity of the constructs. As shown in Table 3, the correlations of all variables are lower than the square root of AVE, thus proving that the constructs have adequate discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). In addition, Henseler et al. (2015) have also suggested using Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio to assess discriminant validity as a criterion. Our results as depicted in Table 4 depicts that the values ranged from 0.255 to 0.819. Since the HTMT values in this study did not exceed the threshold of 0.85 proposed by Kline (2015) and 0.90 as suggested by Gold et al. (2001), it can be inferred that discriminant validity has been ascertained. Green supply chain management Table 3 Discriminant validity: Fornell-Larcker criterion FCD FCD 103 FCP FCQ FPE GP PR SC 0.787 FCP 0.509 0.818 FCQ 0.614 0.502 0.779 FPE 0.409 0.307 0.401 0.784 GP 0.228 0.354 0.204 0.361 0.827 PR 0.339 0.368 0.333 0.534 0.611 0.784 SC 0.28 0.282 0.261 0.493 0.661 0.606 0.719 Notes: Values on the diagonal (bolded) are square root of the AVE while the off-diagonals are correlations. GP = green production, GPR = green procurement, GSCC = green supplier and customer collaboration, FPE = firm environmental performance, FCD = firm competitiveness in delivery, FCP = firm competitiveness in price, and FCQ = firm competitiveness in quality. Table 4 Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT) FCD FCP FCQ FEP GP GPR GSSC FCD FCP 0.520 FCQ 0.769 0.521 FEP 0.424 0.347 0.411 GP 0.299 0.425 0.255 0.358 GPR 0.435 0.370 0.403 0.581 0.676 GSSC 0.337 0.312 0.316 0.516 0.819 0.685 6.3 Structural model To assess the structural model, the R2, standard beta and the corresponding t-values were obtained via a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples, as shown in Table 4. Apart from that, predictive relevance (Q2) and the effect sizes (f2) were also reported (Hair et al., 2014). In Table 5, all hypotheses were supported, except the path of GP to Firm Environmental Performance (beta = -0.072, t = 0.812). GP, PR, and SC explained 33.5% of the variance explained of FEP. FPE, on the other hand, contributes 16.8% to firm competitiveness in delivery, 9.4% to firm competitiveness in price, and 16.1% to firm competitiveness in quality (Table 5). According to Cohen (1988) guidelines, the value of 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35 represent small, medium, and large effects respectively. From Table 5, it can be observed that the effect size (f2) is medium for firm environmental performance to firm competitiveness (cost, quality and delivery), while the effect size for green procurement and supplier and customer collaboration are also medium. GP, green procurement, and supplier and customer collaboration explained 33.5% of the variance of firm environmental performance. The predictive relevance (Q2) for firm environmental performance is 0.187, for firm competitiveness is 0.053 for cost, 0.082 for quality, and 0.089 for delivery. 104 C.L. Tan et al. Table 5 H1 Hypotheses testing Hypothesis Std beta Std error T statistics Decision R square f square GP → FEP 0.427 0.071 5.726** Supported 0.168 0.237 H2 GPR → FEP 0.329 0.073 4.181** Supported 0.094 0.131 H3 GSCC → FEP 0.418 0.075 5.351** Supported 0.161 0.228 H4 FEP → FCD -0.072 0.108 0.812 Not supported 0.335 0.013 H5 FEP → FCP 0.399 0.097 4.141** Supported 0.143 H6 FEP → FCQ 0.31 0.099 3.123** Supported 0.082 Notes: **p< 0.01, *p< 0.05. GP = green production, GPR = procurement, GSCC = supplier and customer collaboration, FEP = firm environmental performance, FCD = firm competitiveness in delivery, FCP = firm competitiveness in price, and FCQ = firm competitiveness in quality. 6.4 Importance-performance matrix analysis The importance-performance matrix analysis (IPMA) has been performed in this study to analyse areas for further improvement. Variables with high importance and low performance can be easy identified through assessing IPMA (Hock et al., 2010). Further from the IPMA results, it contributes as insights for the management to overcome and improve on identified areas with low performance and high importance (Schloderer et al., 2014). Table 6 illustrates the IPMA analysis resulted from the SmartPLS. The importance value is the direct effect of an exogenous variable on an endogenous variable, whereas the performance value is the latent variable score on a scale from 0 to 100. The IPMA results for the endogenous variable of firm environmental performance are presented in Figure 1. The IPMA shows that the endogenous variable firm environmental performance, the highest performance belongs to GP (60.414) whereas the lowest performance is supplier and customer collaboration (50.641). Also, with the aid of the importance-performance matrix, it shows that the most important variable for firm environmental performance is green procurement with a rating point of 0.344. Thus, the results from IPMA analysis describe the areas which need improvements with regards to firm environmental performance is on green procurement. The IPMA of environmental performance reveals that the construct GP has high performance, but it is not an important variable in the prediction of firm environmental performance. Furthermore, it has also proven in Table 5 that GP is not significantly influencing firm environmental performance. Hence, the firm should not focus too much on GP and perhaps should focus more on green procurement and concentrate on enhancing supplier and customer collaboration. Table 6 IPMA results Latent variable Environmental performance Direct effect(importance) Index value (performance) Green production –0.060 60.414 Green procurement 0.344 58.811 Supplier and customer collaboration 0.288 50.641 Green supply chain management Figure 1 7 105 Importance-performance matrix map (see online version for colours) Discussion and conclusions From the above analysis, it can be seen that GSCM has a positive impact on firm environmental performance, which resulted in firm competitiveness with respect to cost, quality and delivery. The relation between GSCM practices and firm performances and firm competitiveness is thus confirmed, as stipulated by previous studies (Chien and Shih, 2007; Eltayeb et al., 2010a; Lefebvre et al., 2003; Li et al., 2004; Mollenkopf and Closs, 2005; Ninlawan et al., 2009; Rao and Holt, 2005; Testa and Iraldo, 2010; Yang et al., 2010; Zhu and Sarkis, 2004; Zhu et al., 2010). The results of the study provide several suggestions for manufacturing companies in Malaysia. In particular the environmental, health, and safety manager, operational manager, quality manager, production manager, and supply chain manager can use the findings from this study to increase firm’s participation in green initiatives along the supply chain and to realise the performance outcomes. The findings from this study indicated that green purchasing and supplier and customer collaboration appeared to have a positive impact on firm performances and competitiveness. These served as motivation to encourage firms to implement GSCM practices. Managers of the firms should view GSCM practices positively instead of an extra burden to the firms. For firms that are interested to implement GSCM practices may start by involving in the two practices that were found to be significantly related to performance outcomes and competitiveness in order to improve the firm’s performance and bring benefit to the society at large. For instance, adhering to the legislation compliances in E&E industry is the most common green purchasing activity which was initiated by the European Union. Firms can further extend to the rest of the green purchasing element such as supplier selection and evaluation based on environmental criteria. Firm overall efficiency will be transmitted to monetary cost saving. These two GSCM practices cover the whole supply chain from purchasing to close loop supply chain. 106 C.L. Tan et al. However, not all green supply chain practices are significant in increasing firm environmental performance. For example, only green procurement and green supplier and customer collaboration have a significant effect on environmental performance and firm competitiveness, while GP is found to have insignificant effect on firm environment performance and firm performance. Firm competitiveness is analysed by the ration of cost/benefit (Testa and Iraldo, 2010) and is measured by efficiency in process and effectiveness in the outcome. Green purchasing emphasised on the balance between cost, quality, delivery, and environmental concept in the green purchasing network. It is necessary to select the right supplier, who can help to ensure that the purchased product contains green attribute. The traditional role of purchasers, such as on-time delivery and delivery of the right part and the right quantity (Handfield et al., 2002) helps to ensure on-time delivery of final products. Green purchasing is also positively related to the quality of products. For example, the Electronic Industry Code of Conducts has helped to ensure suppliers of electronic goods to supply quality product to customers. For supplier and customer collaboration, the exiting collaborative activities in Malaysia concentrate mainly on Type 1 collaboration (Eltayeb et al., 2010b), that is, limited to product forecast sharing and electronic purchase order through electronic data interchange (Whipple and Russell, 2007). In view of the significance of supplier and customer collaboration in ensuring firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness, it is necessary for the parties involved to have more collaborative effort to take advantage of the situation. GP has been found to have a significant influence on firm competitiveness in terms of price (Yang et al., 2010), but not firm competitiveness in terms of quality and delivery. Rao’s (2004) study revealed that in the South-East Asian region, financial limitation and lack of technical know-how had limited the implementation of cleaner and lean production. In this study, GP was found to have an insignificant impact on firm environmental performance and firm competitiveness. Most of the manufacturing perceived that GP requires a huge investment, for instance, substitute the material with environmental-friendly material and redesigning the production floor with environmental design. Due to the constraints faced by most of the manufacturing companies in term of the financial, they do not perceive the GP implementation is possible in the short term. Therefore, the result reveals the insignificant lead to environmental performance. Thus, organisations need to focus their attention on green procurement and green supplier and customer collaboration in order to increase firm environment performance and firm competitiveness. Hence, it can be concluded that GSCM practices in Malaysia are still at the infancy stage. Even though the social responsibility of social awareness has increased, cost/benefit is still the major concern for the majority of Malaysian firm. Besides the identified outcomes, antecedents for GSCM practices need to be identified so that incentives programs can be designed to motivate the implementation of GSCM practices in Malaysian firms. Related regulatory bodies, government, education institutions need to play their respective role to create a sustainability society. Finally, every research is subject to some limitations. This study considers only three GSCM practices which pertain to green purchasing, GP, and supplier and customer collaboration. Future research may include other GSCM practices such as eco-design, supplier management, external GSCM practices, and lifecycle management to widen the research scope. In addition, this study used the cross-sectional approach that measures the variables at a point of time. This approach restricts the ability to prove the direction of Green supply chain management 107 causality. It is preferable to have a sufficient time frame between the implementation of GSCM practices to the time when measurement of firm performance and competitiveness are taken. Longitudinal research would help to validate the causal relationship and to obtain more accurate result. References Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988) ‘Structural equation modelling in practice: a review and recommended two-step approach’, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103, No. 3, pp.411–423. Bendavid-Val, A. and Perine, C. (2003) Environmental Competitiveness: Completing the Competitiveness Paradigm [online] http://archives.smia.info/2003/SMIA_Bendavid-Val.pdf (accessed 10 July 2011). Burke, S. and Gaughran, W.F. (2005) ‘Intelligent environmental manegement for SMEs in manufacturing’, Robotics and Computer-Integrated Manufacturing, Vol. 22, Nos. 5–6, pp.405–415. Chien, M.K. and Shih, L.H. (2007) ‘An empirical study of implementation of green supply chain management practices in the electicical and electronic industry and their relationship to organizational performance’, International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp.383–394. Choi, S.B., Min, H., Joo, H.Y. and Choi, H.B. (2017) ‘Assessing the impact of green supply chain practices on firm performance in the Korean manufacturing industry’, International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp.129–145. Ciliberti, F., Pontrandolfo, B., and Scozzi, P. (2008) ‘Logistics social responsibility: standard adoption and practices in Italian companies’, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 113, No. 2, pp.528–545. Cohen, J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Hillsdale, NJ. Eltayeb, T., Zailani, S. and Ramayah, T. (2010) ‘Green supply chain initiatives among certified companies in Malaysia and environmental sustainability:Investigating the outcomes’, Journal of Resource, Conservation and Recycling, Vol. 55, No. 5, pp.495–506. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981) ‘Discriminant validity’, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp.39–50. Freedman, M. and Jaggi, B. (1992) ‘An investigation of the long-run relationship between pollution performance and economic performance: the case of pulp and paper firms’, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, December, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp.315–336. Gilbert, S. (2000) ‘Greening supply chain: enhancing competitiveness through green productivity’, Report of the Top Forum on Enhancing Competitiveness through Green Productivity, China, 25–27 May. Gold, A. H., Malhotra, A. and Segars, A. H. (2001) ‘Knowledge management: an organizational capabilities perspective’, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp.185–214. Grant, R.M. (1991) ‘The resource-based theory of competitive advantage’, California Management Review, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp.114–135. Hair, J.F, Anderson, R.L. and Tatham, W.C. (2014) Multivariate Data Analysis, Parentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Hair, J.F., Black, W.C., Babin, B.J. and Anderson, R.E. (2010) Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed., Prentice Hall, New Jersey. Handfield, R.B., Walton, S.V., Seegers, L.K. and Melnyk, S.A. (1997) ‘Green’ value chain practices in the furniture industry’, Journal of Operations Management, Vol. 15, No.4, pp.293–315. 108 C.L. Tan et al. Handfield, R., Walton, S., Sroufe, R. and Melnyk, S. (2002) ‘Applying environmental criteria to supplier assessment: a study in the application of the analytical hierarchy process’, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 141, No. 1, pp.70–87. Henseler, J., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2015) ‘A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp.115–135. Hervani, A.A., Helms, M.M. and Sarkis, J. (2005) ‘Performance measurement for green supply chain management’, Benchmarking: An International Journal, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp.330–353. Hock, C., Ringle, C.M. and Sarstedt, M. (2010) ‘Management of multi-purpose stadiums: importance and performance measurement of service interfaces’, International Journal Services Technology and Management, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp.188–207. Iraldo, F., Testa, F. and Frey, M. (2009) ‘Is an environmental management system able to influence environmental and competitive performance? The case of the eco-management and audit scheme (EMAS) in the European Union’, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, No. 16, pp.1444–1452. Kline, R.B. (2015) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 4th ed., The Guilford Press, New York. Lee, S.M., Kim, S.T. and Choi, D. (2012) ‘Green supply chain management and organizational performance’, Industrial Management & Data Systems, Vol. 112, No. 8, pp.1148–1180. Lefebvre, E., Lefebvre, L.A. and Talbot, S. (2003) ‘Determinants and impacts of environmental performance in SMEs’, R&D Management, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp.263–283. Levy, S.R. (1995) ‘Sources of current and future funding’, New Directions for Student Services, Vol. 1995, No. 70, pp.39–49. Li, S., Ragu-Nathan, B., Ragu-Nathan, T.S. and Rao, S.S. (2004) ‘The impact of supply chain management practices on competitive advantage and organizational performance’, Omega, Vol. 34, No. 2, pp.107–124. Lopez-Gamero, M.D., Molina-Azorın, J.F. and Claver-Cortes, E. (2009) ‘The whole relationship between environmental variables and firm performance: competitive advantage and firm resources as mediator variables’, Journal of Environmental Management, Vol. 90, No. 10, pp.3110–3121. Menzel, V., Smagin, J. and David, F. (2010) ‘Can companies profit from greener manufacturing?’, Measuring Business Excellence, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp.22–31. Mohan Kumar, K., Abd Rahman, A., Jayaraman, K. and Abdul Rahim, S. (2017) ‘Conceptualization of a research model for sustainable logistics practices and logistics transport performance’, Jurnal Pengurusan, Vol. 51, No. 2017, pp.147–158. Mollenkopf, D.A. and Closs, D.J. (2005) ‘The hidden value in reverse logistics’, Supply Chain Management Review, Vol. 9, No. 5, pp.34–43. Nawrocka, D. and Parker, T. (2009) ‘Finding the connection: Environmental management systems and environmental performance’, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp.601–607. Ninlawan, C., Seksan, P. and Pilada (2009) ‘The implementation of green supply chain’, Management Practices in Electronics Industry, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp.933–956. Porter, M.E. (1990) The Competitive Advantage of Nations, Free Press, New York. Poser, C., Guenther, E.,and Orlitzky, M. (2012) ‘Shades of green: using computer-aided qualitative data analysis to explore different aspects of corporate environmental performance’, Journal of Management Control, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp.413–450. Ramakrishnan, P., Haron, H. and Goh, Y.N. (2015) ‘Factors Influencing green purchasing adoption for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia’, International Journal of Business and Society, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp.39–56. Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H. and Mumtaz A. M. (2016) Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: An Updated and Practical Guide to Statistical Analysis, Pearson, Malaysia. Green supply chain management 109 Rao, P. (2004) ‘Greening production: a South-East asian experience’, Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp.289–320. Rao, P. and Holt, D. (2005) ‘Do green supply chains lead to competitiveness and economic performance?’ International Journal of Operations and Production Management, Vol. 25, No. 9, pp.898–916. Ringle, C.M., Wende, S. and Becker, J.M. (2015) SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS [online] http://www.smartpls.de (accessed 10 March 2011). Schloderer, M.P., Sarstedt, M. and Ringle, C.M. (2014) ‘The relevance of reputation in the nonprofit sector: the moderating effect of socio-demographic characteristics’, International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, Vol. 19, No. 2, pp.110–126. Schultze, W. and Trommer, R. (2012) ‘The concept of environmental performance and its measurement in empirical studies’, Journal of Management Control, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp.375–412. Sharma, S. and Vredenburg, H. (1998) ‘Proactive corporate environmental strategy and the development of competitively valuable organizational capabilities’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp.729–753. Shen, M. (2010) Corporate Environmental Strategy and Practises: Antecedents and Consequences, Proquest Dissertation, UMI No. 1479625. Singh, R.K., Garg, S.K. and Deshmukh, S.G. (2008) ‘Strategy development by SMEs for competitiveness: a review,’ International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp.525–547. Steinle, C. and Schiele, H. (2008) ‘Limits to global sourcing? Strategic consequences of dependency on international suppliers: cluster theory, resource-based view and case studies’, Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp.3–14. Supply Chain Council (2010) SCOR Frameworks, Supply Chain Council [online] http://www.cognizant.com/InsightsWhitepapers/Creating_a_Green%20Supply_Chain_WP.pdf (accessed 9 November 2010). Tan, C.L., Goh, Y.N., Yeo, S.F., Ching, S.L. and Chan, H.S. (2017) ‘An examination of the factors influencing the green initiative and competitiveness of private higher education institutions in Malaysia’, Jurnal Pengurusan, Vol. 51, No. 2017, pp.1–20. Tan, C.L., Suhaiza Hanim, M.Z., Sieow, C.T. and Mohd Rizaimy, S. (2016) ‘The impact of green supply chain management practices on firm competitiveness’, International Journal of Business Innovation and Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp.539–558. Tan, C.L., Yeo, S.F. and Low, C.H. (2018) ‘Green supply chain management practices and organizational performance: an empirical study in Malaysian manufacturing firms’, Jurnal Pengurusan, Vol. 58, No. 2018, pp.1–20. Tan, J. and Zailani, S. (2009) ‘Green value chain in the context of sustainability development and sustainble competitive advantage’, Global Journal of Environmental Research, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp.234–245. Tan, X.C., Liu, F., Cao, H.J. and Zhang, H. (2002) ‘A decision-making framework model of cutting fluid selection for green manufacturing and a case study’, Journal of Material, Process, and Technology, Vol. 129, No. 1, pp.467–470. Testa, F. and Iraldo, F. (2010) ‘Shadows and lights of GSCM (green supply chain management): determinants and effects of these practices based on a multi-national study’, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 18, Nos. 10–11, pp.953–962. Vachon, S. and Klassen, R.D. (2008) ‘Environmental management and manufacturing performance: The role of collaboration in the supply chain’, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 111, No. 2, pp.299–315. Whipple, J.M. and Russell, D. (2007) ‘Building supply chain collaboration: a typology of collaborative approaches’, The International Journal of Logistics Management, Vol. 18, No. 2, pp.174–196. 110 C.L. Tan et al. White, A. D. and Mohdzain, M. B. (2009) ‘An innovative model of supply chain management: a single case study in the electronic sector’, International Journal of Information Technology and Management, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp.69–84. Yang, M.G., Hong. P. and Modi, S.B. (2010) ‘Impact of lean manufacturing and environmental management on business performance: an empirical study of manufacturing firms’, International Journal of Production Economics, Vol. 129, No. 2, pp.251–261. Yu, Y., Zhang, M. and Huo, B. (2017) ‘The impact of supply chain quality integration on green supply chain management and environmental performance’, Total Quality Management & Business Excellence [online] https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2017.1356684 (accessed 29 March 2018). Zhu, Q. and Sarkis, J. (2004) ‘Relationship between operational practies and performance among early adopters of green supply chain management practices in Chinese manufacturing enterprises’, Journal of Operation Management, Vol. 22, No. 3, pp.265–289. Zhu, Q. and Sarkis, J. (2006) ‘An inter-sectoral comparison of green supply chain management in china: drivers and practices’, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 14, No. 5, pp.472–486. Zhu, Q., Crotty, J. and Sarkis, J. (2008) ‘A cross-country empirical comparison of environmental supply chain management practices in the automotive industry’, Journal of Production and Operation Management, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp.467–488. Zhu, Q., Geng, Y., Fujita, T. and Hashimoto, S. (2010) ‘Green supply chain management in leading manufacturers: case studies in Japanese large companies’, Management Research Review, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp.380–392. Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J. and Geng, Y. (2005) ‘Green supply chain mangement in China: pressure, practices and performance’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, Vol. 25, No. 6, pp.449–468. Zhu, Q., Sarkis, J. and Lai, K.H. (2006) ‘Green supply chain implications for ‘closing the loop’, Transportation Research Part, Vol. 44, No. 1, pp.1–18. Zorpas, A. (2010) ‘Environmental mangement systems as sustainable tools in the way of like for the SME and VSMEs’, Bioresource, Vol. 101, No. 6, pp.1544–1557. Green supply chain management 111 Appendix Table A1 Measurement items for the studied variables Firm environmental performance • Air emission of my organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. • Hazardous substance or waste of my organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. • Consumption for hazardous/harmful/ toxic materials of my organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. • Frequency of environmental accidents of may organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. • The indirect or direct material usage through green improvement programs of my organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. • My organisation complying to environment law, regulations and standards, improved of environmental situation as compared to my competitor. • Waste water and solid waste emission of my organisation has been reduced as compared to my competitor. Firm competitiveness in price • My organisation offer competitiveness price compared to may competitor. • My organisation offer price as low or lower than our competitor. • My organisation direct manufacturing cost/ production cost reduced compared to my competitor. • My organisation total product cost reduced compared to my competitor. • My organisation raw material cost reduced compared to my competitor. Firm competitiveness in quality • My organisation able to compete based on quality • My organisation offer products that are highly reliable as compared to my competitor. • My organisation offer products that durable as compared to my competitor. • My organisation offer high quality product to our customer as compared to my competitor. • My organisation offer product which is conformance to design Firm competitiveness; delivery • My organisation deliver needed kind of product as compared to my competitor. • My organisation delivers customer order on time as compared to my competitor. • My organisation meeting delivery due date as compared to my competitor. • My organisation order fulfilment speed increased as compared to my competitor. Source: Eltayeb et al. (2010), Li et al. (2004) and Zhu and Sarkis (2004) 112 Table A1 C.L. Tan et al. Measurement items for the studied variables Green purchasing • My organisation selects their supplier based on environmental criteria. • My organisation use a questionnaire to collect information about its suppliers’ environmental aspects, activities, and/ or management system. • My organisation makes sure that its purchased products must contain green attribute such as recycled or reusable items. • My organisation makes sure that its purchased products must not contain green environmental undesirable item such as lead or other hazardous or toxic materials. • My organisation evaluates its suppliers based on specific environmental criteria. • My organisation evaluates the environmental aspects of its second-tier suppliers. Green production • My organisation utilised environmentally friendly raw materials in its production. • My organisation implements cleaner technology process for energy, water and waste saving in its production process. • My organisation takes into consideration environmental design in its production. • My organisation implements internal recycling of materials in its production. Green supplier and customer collaboration • My organisation provide design specification that include environmental requirement for purchased item • My organisation cooperates with supplier for meeting environmental objectives • My organisation request suppliers to obtain ISO14001 • My organisation performs environmental audit for suppliers’ internal management. • My organisation cooperates with customer for eco-design. • My organisation cooperates with customer for cleaner production. • My organisation cooperates with customer for green packaging Source: Eltayeb et al. (2010), Li et al. (2004) and Zhu and Sarkis (2004)