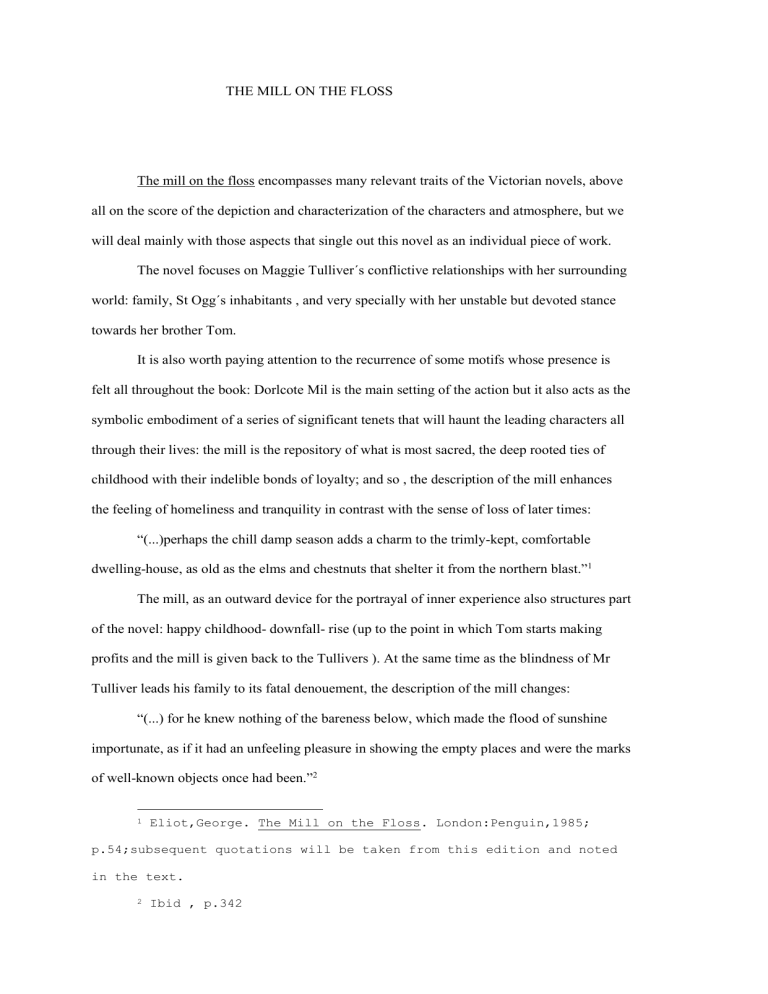

THE MILL ON THE FLOSS The mill on the floss encompasses many relevant traits of the Victorian novels, above all on the score of the depiction and characterization of the characters and atmosphere, but we will deal mainly with those aspects that single out this novel as an individual piece of work. The novel focuses on Maggie Tulliver´s conflictive relationships with her surrounding world: family, St Ogg´s inhabitants , and very specially with her unstable but devoted stance towards her brother Tom. It is also worth paying attention to the recurrence of some motifs whose presence is felt all throughout the book: Dorlcote Mil is the main setting of the action but it also acts as the symbolic embodiment of a series of significant tenets that will haunt the leading characters all through their lives: the mill is the repository of what is most sacred, the deep rooted ties of childhood with their indelible bonds of loyalty; and so , the description of the mill enhances the feeling of homeliness and tranquility in contrast with the sense of loss of later times: “(...)perhaps the chill damp season adds a charm to the trimly-kept, comfortable dwelling-house, as old as the elms and chestnuts that shelter it from the northern blast.”1 The mill, as an outward device for the portrayal of inner experience also structures part of the novel: happy childhood- downfall- rise (up to the point in which Tom starts making profits and the mill is given back to the Tullivers ). At the same time as the blindness of Mr Tulliver leads his family to its fatal denouement, the description of the mill changes: “(...) for he knew nothing of the bareness below, which made the flood of sunshine importunate, as if it had an unfeeling pleasure in showing the empty places and were the marks of well-known objects once had been.”2 1 Eliot,George. The Mill on the Floss. London:Penguin,1985; p.54;subsequent quotations will be taken from this edition and noted in the text. 2 Ibid , p.342 The river also takes a part in the structuration of the novel (this aspect will be further dwelt on) and so does St Ogg´s, the second main setting which has an influence on the maturity and growing up of Maggie and Tom: they are introduced to a world of social mores; from the self-centredness of childhood and early adolescence they undergo a transition that for good or for ill intervenes in their development. Their horizon widens as a direct consequence of the new environment they are ushered in. Society in St Ogg´s is shaped by a set of customabiding people, social conventions and narrowness in which Tom and Maggie are to rebrand themselves, learn the complexity of the social codes for courtly love or any kind of intercourse. Eliot´s description is minute as to the habits of St Ogg´s people thereby providing us with an accurate, sharp insight as regards to the conditionings present in a small town microcosm: “(...)Mrs Pullet could never enter St Ogg´s again because “acquaintances” knew it all.” Or “the ladies of St Ogg´s were not beguiled by any wide speculative conceptions; but they had their favourite abstraction, called society, which served to make their consciences perfectly easy in doing what satisfied their own egoism.”3 We also get to know both worlds: the privileged layers sphere ( Guests, Wakems, Deanes ) and the humble townsfolk and working people (Bob Jakin, Maggie working for Dr Kenn ) which sharply makes a distintion between the hegemonic influence exerted by wealthy people and the simple acceptance of facts on the part of worst-off men and women. As for the time in which the action takes place, it also serves the purpose of structuring the novel. The span in which the action occurs is of some ten years. The narration starts off when Maggie is eight or nine years and finishes when she is nineteen. In this interval of time we are witnesses of the characters´ developing personality; as action unfolds, Maggie and Tom evolve towards maturity, they go through different stages: school at Mr Stelling, Maggie´s visits to Tom, return home, silent years of work, dejection and hopes, adolescence and early adulthood (We must have into account that “teenagers” are a product of our present society and that at George Eliot´s times a child became a young adult without that gap we today call 3 Ibid , p. 630 and637. adolescence, thereby my use of “adulthood”). Time and space give us a hindsight, a retrospective picture of places, circumstances and situations, itemised by the author to proffer a global view on the book and a more complete understanding of the trials and tribulations of the protagonists. With respect to the narration, we can talk here of an omniscient narrator: characters are seen from outside and the narrator knows their innermost feelings and actions. This narrator also affords to show indulgence towards some of the characters´ shortcomings (Tom, for instance) entreating the reader not to pass severe judgement on them. The actions of the protagonists are escribed through a twofols process of diegesis (summing up the actions of the characters in retrospect , for instance, explaining Maggie´s inner drives to act ina certain way) and mimesis (characters expressing themselves by means of dialogue). Added to that we find in the first chapter a sort of frame narration in which the narrator addresses an unknown hearer, first to make him/her participate of the recollection of a visit to Dorlcote mill: “And this is Dorlcote mill. I must stand a minute or two here on the bridge(...)”4 In this sort of reverie, the narrator pictures in his/her mind dusk at the mill, and we have the first description of Maggie followed immediately by a return to the present situation in which the narrator is sitting down recounting this reminiscence of the mill to a silent listener ( this introduction to the story of the Tullivers also resembles that of the opening of Wuthering Heights ). This sort of preface is narrated in the first person and addressed to an unknown “you” “I was going to tell you(...)”5 that has the function of bringing the reader near the situation that is being talked of. The readers can feel that the speaker is forthrightly addressing them and so, contributing to the realism, directness and vividness of the subsequent narration. This exposition of a state of affairs opens up the next chapter where we are made familiar with the Tullivers, thereby bridging the gap between the reality of the speaker and the reality of the 4 Ibid , p.53 5 Ibid , p.55 events he/she is going to narrate. The whole of the narration is made in the third person with occasional digressions on some points and the final conclusion responds to this mixture of speculation-narration in which we are not brought back to the scope of speaker-listener of the first chapter. This book does not deal with flat characters, they are seen under different perspectives although here we must draw a line as far as main and secondary characters are concerned. As to Maggie, the leading character of The mill on the floss, she is first described ina dialogue between Mr and Mrs Tulliver as “too cute for a woman” and on her appearance the narrator speaks of a “small mistake of nature”6, thenceforth stress is laid on Maggie´s rebelliousness and imagination as well as her being the apple of Mr Tulliver eyes. Right from the beginning we also appreciate a sense of unswerving fealty and admiration towards Tom. Maggie is an instinctive creature struggling her way in a world of duty and obedience; her spontaneity places her somehow outside the all-pervading scope of orthodox society. Her physical features, brown skin and dark eyes, also confer on her a gypsy-like, alienating uniqueness that pains her mother´s sense of social order. She is not one of the Dodsons, neither in demeanour nor in physical traits (in fact she attempts to elope with a gypsies´ tribe, regarding them more akin to her than her own family. Along with all this, Maggie is portrayed as an emotional, sensitive person easily moved by other people ´s misfortunes (like Philiph´s ), but we can not make a far too cut-and-dried picture of Maggie: the ordeal she undergoes reveals us a stoic, self-effacing quality that has emerged out of a twist of fate and that is adamant in the repression of what was erstwhile one of her best assets: joy of life. Maggie´s nature is further explored and enriched in all its complexity: like the floss, she has a story of cruelty, passion, passivity and mystery, she lives by the river, the river takes her away to an obscure future with Stephen and finally swallows her in a single instant in which they are one and the same. Tom, on the other hand, is presented as a matter-of-fact, down to earth boy, but not devoid of such qualities as will-power, steadiness and brotherly love. Mr Tulliver renders his 6 Ibid , p.60 and 61 description in the following terms “(...) as Tom hasn´t got the right sort o´ brains for a smart fellow. I doubt he´s a bit slowish (...).” 7 Tom epitomises the narrow spirit of the Dodsons, their petty lives and petty problems but also the uprightness that makes him thrive in moments of crisis. At all events, however difficult Tom and Maggie´s relationship may have been, they are inextricably bound to each other and so it is stated in their epitaph: “In their death they were not divided.”8 As for Stephen and Philiph, they incarnate two different sides of Maggie: passion and compassion and they are important in so far as they spark off a split in Maggie´s affections making her conscious of the non-univocal undercurrents in human experience. Following this aforementioned notion of split, we could use it to refer to both Dodsons and Tullivers. The Tullivers are wayward and thoughtless to the extent of losing everything, Mr Tulliver, a diehard individual, as contrary to the gregariousness of the Dodsons, rejects the accepted criteria, the conventions, the meritocracy which seems, for the Dodsons, the preserve of an elite distinguished by social success. Whenever the Dodsons´ ossyfying presence is let felt, the Tullivers (Maggie, Mr Tulliver, auntie Gritty )oppose their luxuriant vitality and this struggle between the two sides gives the book its tragicomic undertones: “that´s the worst on ´t wi´ the crossing o´ breeds: you can never justly calkilate what ´ll come on ´t”9 All in all, our perception of the characters is given by means of dialogue, mainly through the use of reported speech, we get to know their feelings, intentions, thoughts...but their personalities are also rounded by explanations, on the part of the narrator, of a more analytical, and far-reaching kind: laws that seem to govern characters´ actions (which are exposed by Eliot in letters to friends), some principles recurrent in human behaviour, digressions on different aspects of the literary personae...Through this twofold approach: 7 Ibid , p. 59. 8 Ibid , p. 657 edition. 9 Ibid ,p. 59 and also in the front page of the first dialogue and narration,we know how the characters interact with one another and how the interfused social and individual elements contrive to unleash all the forces lurking in the human soul. THE MILL ON THE FLOSS BRUNHILDE ROMAN IBAÑEZ