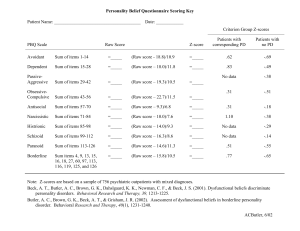

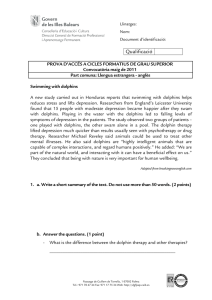

Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014) 236–239 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Affective Disorders journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jad Brief report Reliability and validity of the beck depression inventory-fast screen for medical patients in the general German population Sören Kliem a,n, Thomas Mößle a, Markus Zenger b, Elmar Brähler b a b Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony, Germany University of Leipzig, Department of Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology, Germany art ic l e i nf o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 18 September 2013 Received in revised form 6 November 2013 Accepted 7 November 2013 Available online 17 December 2013 Background: The Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screen (BDI-FS) is a self-report instrument for the detection of depression in youths and adults. It measures the severity of the depression, corresponding to the non-somatic criteria for the diagnosis of a major depression according to DSM-5. Until now the psychometric properties of the instrument have not been studied in the general population. Methods: In 2012, a survey representative for the Federal Republic of Germany was conducted. In addition to the BDI-FS, further self-rating questionnaires as well as a demographic questionnaire were administered. Results: Altogether, 4480 people were surveyed with a return rate of 56.1% (N¼ 2467 persons). Approximately 53% of those surveyed were women. The average age was 49.4 years (SD¼ 18.0), with a range of 14–91 years. For the BDI-FS total-scores, a coefficient α of .84 was determined (women: α ¼ .83; men: α ¼ .85). In addition, a convergent validity (r ¼ .67) was determined with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). The discriminant validity of the BDI-FS can be classified as satisfactory. Based on a confirmatory factor analysis, the one-dimensionality of the BDI-FS could be confirmed, achieving very good fit indices (total sample: RMSEA ¼.058, CFI ¼.990, TLI¼ .986). An additional invariance analysis regarding gender, different age groups and their interaction resulted in strict invariance for the different multi-group analyses. Limitations: Studies regarding stability have yet to be undertaken. A standard diagnostic interview for depression was not included. Conclusion: The results support the reliability and validity of the BDI-FS for use with the general German population. Although in the present studies the BDI-FS was superior to the PHQ-9 in terms of its ability to discriminate between depressive and somatic symptoms, in future investigations the diagnostic efficiency of the BDI-FS should be compared with this and other depression inventories (e.g., PHQ-2, PHQ-8, and CES-D). & 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Depression Screening Primary care Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screen Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care 1. Introduction The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1996), the Hospital Depression Scale (HADS-D; Zigmond and Snaith, 1983), and the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9; Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) provide selfassessment instruments that are used worldwide for identifying the severity of a depression and can also be used for screening in the general population as well as in primary care (Gilbody et al., 2007). In spite of the widespread use of these instruments, the question was repeatedly asked whether the inclusion of statements regarding somatic complaints and performance can lead to a false increase in the prevalence or to an over-assessment of the severity of depression for patients with underlying somatic diseases (e.g., Mitchell et al., 2012; Nan et al., 2012; Strober and Arnett, 2010). For example, for patients with diabetes, cancer, heart disease, pneumonia, or substance abuse, somatic symptoms such as fatigue or exhaustion can be recorded as symptoms of a depression, although they should possibly be evaluated as the result of a physical illness. Based on these considerations, in 1997 the “Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care” (BDI-PC) was developed by Beck et al. (1997), with the goal of reducing the number of false screening decisions within the context of primary health care. In 2000, it was published as the “Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screen for Medical Patients” (BDI-FS; Beck et al., 2000). 1.1. Aims of the study n Correspondence to: Criminological Research Institute of Lower Saxony, Lützerodestraße 9, 30161 Hannover, Germany. Tel.: þ49 511 34836 70; fax: þ49 511 34836 10. E-mail address: [email protected] (S. Kliem). 0165-0327/$ - see front matter & 2013 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.024 Although appropriate psychometric characteristics of the BDIFS have been reported in a number of studies, the reliability and validity of this instrument for a large sample of German speaking S. Kliem et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014) 236–239 237 2.3. Statistical analyses people has not yet been investigated. In addition, no characteristic psychometric values have been reported from large population samples. The aim of this study is to investigate the reliability, validity, and factorial structure as well as the factorial invariance of the BDI-FS in a German population sample. Internal consistency of the BDI-FS is reported as coefficient α. Selectivity was determined as the correlation of the item with the sum of all other items. Additionally, item difficulty coefficients were calculated. To determine convergent and discriminatory validity of the BDI-FS, correlations with the PHQ-9, the GAD-2, and the SSS-8 were calculated. Furthermore, bivariate correlations were calculated with socio-demographic risk factors for depression, such as gender, age, level of education (0¼no high school graduation, 1¼ high school graduation), work status (0¼ unemployed, 1¼employed), monthly net income, and partnership status (0¼no partnership, 1¼partnership); p-Values were Bonferroni corrected. To test for the one-factor solution of the BDI-FS, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted. Given only four response categories, maximum likelihood estimation was deemed inappropriate (DiStefano and Hess, 2005; Lubke and Muthén, 2004). Thus, a polychoric correlations matrix using the mean- and variance-adjusted weighted least square estimator (WLMSV; Flora and Curran, 2004) was calculated, which has been shown to be robust to violations of normality (e.g., Dumenci and Achenbach, 2008). To evaluate goodness of fit of the relevant model, we considered three different criteria: the root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval for assessing absolute model fit, as well as the Comparative Fit-Index (CFI) and Tucker Lewis Index (TLI) as measures of relative fit. RMSEA values o.050 as well as CFI and TLI scores 4.950 are suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999) for a good model fit. Furthermore, several measurement invariance tests using multigroup factor analyses were conducted across gender (group 1: men; group 2: women), age (group 1: o51 years [Median-Split]; group 2: Z51 years) and gender age (group 1: women, o51 years; group 2: woman, Z51 years; group 3: men, o51 years; group 4: men, Z51 years) using the same estimator as in the CFA (WLSMV). Measurement invariance tests were performed using the sequential strategy discussed by Meredith and Teresi (2006). As recommended by Chen (2007), CFI differences with a cut-off value of ΔCFI 4.01 were used to test the different stages of measurement invariance. Data analysis was carried out with the R packages “lavaan” (Rosseel et al., 2011) and “semTools” (Pornprasertmanit et al., 2013). 2. Methods 2.1. Study design and participants Data were collected between May and June 2012. A crosssectional study of a representative random sample of the general German population was conducted by an independent institute for opinion and social research (USUMA, Berlin; see Gierk et al., 2013, for a detailed description). The criteria for inclusion were an age of Z14 years and sufficient ability to understand the written German language. After a socio-demographic interview, the participants completed self-report questionnaires regarding physical and psychological symptoms in the presence of (but without any interference from) the interviewer. Interviewers were controlled by sending pre-stamped postcards to the participants (40%, randomly chosen). About 53% of the postcards were returned; all of them confirmed a proper conduct. 2.2. Measures The BDI-FS is a seven-item questionnaire which assesses dysphoria, anhedonia, suicidal ideation, and cognition-related symptoms using seven statements ranging in intensity. Translation of the German version (Kliem and Brähler, 2013) followed state-ofthe-art procedures in cross-cultural assessment (Bracken and Barona, 1991). Scores on the BDI-FS range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating more depressive symptomatology. The PHQ-9 (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) is a self-administered depression module, which scores each of the nine DSM-5 criteria as 0 (“not at all”) to 3 (“nearly every day”) and showed high internal consistency (α ¼ .89; Kroenke et al., 2001, study at hand: α ¼.86). The Somatic Symptom Scale (SSS-8; Gierk et al., 2013) was used to assesses somatic symptom strain. The Inventory comprises eight items (e.g., stomach or dizziness), with each symptom scored from 1 (“not bothered at all”) to 5 (“bothered very strongly”) within the last seven days (study at hand: α ¼.82). In the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-2; Kroenke et al., 2009), two main symptoms of a generalized anxiety disorder are assessed on a four-point scale (0 ¼“not at all” to 3 ¼“almost every day”). The GAD-2 showed high internal consistency in the general population (α ¼.75; Löwe et al., 2010, study at hand: α ¼ .75). 3. Results 3.1. Sample characteristics The initial sample consisted of 4480 persons, of which 2515 (56.1%) participated in the full study. Major reasons for non-participation were, household not present at all three visits (12.9%); household refused to provide information (13.7%); and target person refused to be interviewed (13.3%). The final sample included 53% females, the average age was 49.4 years (SD¼ 18.0) with a range of 14–91 years. To assess the generalizability of our results to the German population, we Table 1 Mean (M), standard deviation (SD), item difficulty (Pi), corrected item-total correlation (rit), and group differences for the BDI-FS Items and total scores. Statement about Sadness Pessimism Past failure Loss of pleasure Self-dislike Self-criticalness Suicidal thoughts Total score Total Male Female Group differences M SD Pi rit M SD Pi rit M SD Pi rit t df p .15 .23 .13 .34 .08 .22 .04 1.14 .38 .49 .42 .57 .32 .46 .20 2.08 5.0 7.7 4.3 11.3 2.7 7.3 1.3 5.4 .66 .69 .57 .60 .63 .52 .47 – .12 .22 .13 .32 .09 .20 .04 1.11 .35 .51 .42 .57 .32 .46 .20 2.11 4.0 7.3 4.3 10.7 3.0 6.7 1.3 5.2 .67 .71 .65 .63 .65 .56 .53 – .15 .23 .13 .34 .08 .22 .04 1.18 .38 .49 .42 .57 .32 .46 .20 2.05 5.0 7.7 4.3 11.3 2.7 7.3 1.3 5.6 .67 .71 .65 .63 .65 .56 .53 – 1.90 .17 .09 .79 .26 1.47 .17 .87 2500 2492 2498 2498 2502 2497 2484 2492 .057 .863 .925 .428 .791 .143 .869 .387 238 S. Kliem et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014) 236–239 Table 2 Correlation coefficients between the BDI-FS and other self-rating questionnaires as well as socio-demographic risk factors of depression. BDI-FS PHQ-9 GAD-2 SSS-8 Socio-demographic risk factors of depression Age Gender (0 ¼male; 1¼ female)a Education (0 ¼ no high school graduation, 1¼ high school graduation)a Work status (0 ¼unemployed, 1¼employed)a Monthly net income Partnership status (0 ¼no; 1 ¼yes)a BDI-FS PHQ-9 GAD-2 SSS-8 1 .67nnn .60nnn .57nnn – 1 .65nnn .71nnn – – – .55nnn – – – 1 .20nnn .05nn .18nnn 32nnn .24nnn .09nnn .16nnn .05nn .14nnn .19nnn 13nnn .07nnn Note: PHQ-9 ¼ Patient Health Questionnaire-9, GAD-2 ¼Generalized Anxiety Disorder Assessment-2, SSS-8 ¼PHQ-Somatic-Symptom-Short-Form. a Spearman correlation coefficient was used. po .05. p o.01. nnn p o.001. n nn compared the demographic characteristics of our sample with the demographic data of the German population. On a descriptive level (due to the large sample size, even small differences would become significant) we found only one demographic variable (non-German nationality) that differed substantially between participants of our study and the German general population (3.8% vs. 8.8%). 3.2. Item characteristics Table 1 displays means, standard deviations, item difficulties and the corrected item-total correlation values for the items of the BDI-FS as well as for the sum score. At the item level, there were no statistically significant differences in average values between men and women. 3.3. Internal consistency Regarding the total value of the BDI-FS, the internal consistency for the total sample was α ¼.84 (men: α ¼.85, women: α ¼.83). This value is comparable to the samples of the American manual (α ¼ .85–.88; Beck et al., 2000). 3.4. Factorial validity and invariance All assessed indices showed an adequate to very good model fit for the total sample (RMSEA ¼ .058, 90% CI [.049,.074], CFI ¼.990, TLI¼ .986). Furthermore, factor loadings were high (.73–.90). Regarding factorial invariance, strict invariance between different age and gender groups can be assumed.1 3.5. Construct validity As can be seen in Table 2, there was a strong correlation between the BDI-FS and the PHQ-9 (r ¼.67, po .001). Although the correlations of the BDI-FS with the GAD-2 and the SSS-8 can be regarded as high, too, they are still lower than the values determined for the comparable correlations with the PHQ-9. Applying a significance test by Meng et al. (1992), the correlations between the BDI-FS/SSS-8 and PHQ-9/SSS-8 (r ¼.57 vs. r ¼.71; Z¼ 12.00; po .001) as well as the correlations between the BDI-FS/GAD-2 and PHQ-9/GAD-2 (r ¼.60 vs. r ¼.65; Z¼ 4.17; 1 The complete results of the measurement invariance analysis regarding age, gender and age gender can be provided on request. po .001) differed significantly. Correlations between the BDI-FS and socio-demographic risk factors are shown in Table 2. 4. Discussion The present study was the first to investigate the psychometric quality of the BDI-FS using a German representative population sample. Based on coefficient α, the instrument can be assessed as reliable. The one-dimensionality of the BDI-FS was confirmed on the basis of CFAs. Furthermore, the analyses showed comparable factor structures in the samples that were studied (age, gender, age gender), which should allow for an undistorted comparison of the sum scores. The existence of strict invariance and the associated possibility of undistorted screening decisions through BDI-FS values, appear to be particularly relevant in this regard (e.g., Millsap and Kwok, 2004). Furthermore, the reported correlation between the BDI-FS and the PHQ-9 (r ¼.67) lies within the range of previous studies using a variety of depression inventories (r¼ .44–.86; Kliem and Brähler, 2013). The correlation with an anxiety inventory (GAD-2; r ¼ .60) was also comparable with the results of previous studies (r ¼.53–.86; Kliem and Brähler, 2013). Based on these results, the ability of the BDI-FS to differentiate between symptoms of anxiety and depression must currently be described as limited. However, it should be noted that this correlation is comparable to those of other depression inventories, such as the PHQ-9 (in this study r ¼.65), the BDI-II (r ¼.37–.60; Hautzinger et al., 2009), or the PHQ2 (r ¼.61; Löwe et al., 2010). Regarding somatic symptoms (SSS-8), the BDI-FS can be deemed to have adequate discriminant validity. 4.1. Limitations In spite of a number of strengths of this study, for example, its large sample size and representativeness, there are certain limitations to be mentioned. First, the response rate was only 56.1%. A lower response rate compared to clinical studies is, however, quite common in general population studies and our response rate is beyond that comparable to other general population surveys (e.g., Aromaa et al., 2011; Radloff, 1977). In addition, a selection bias seems unlikely, since the study sample corresponds to data from the general population with regard to demographic characteristics. Only the percentage of subjects with non-German nationality differed substantially from the German general population. There was, however, no significant difference between participants with and without German nationality with respect to BDI-FS scores. S. Kliem et al. / Journal of Affective Disorders 156 (2014) 236–239 Hence, a distortion of validity by this slight imbalance seems unlikely. Second, the study lacks an additional clinical interview with which the diagnostic efficiency of the BDI-FS could have been studied. However, good sensitivity and specificity, have already been demonstrated by numerous studies with various medical settings (see Kliem and Brähler, 2013). Third, since the study sample is representative of the general population of Germany, comparisons with western European and white American populations seems appropriate. Comparisons with countries with a high cultural heterogeneity are not appropriate. 4.2. Conclusion The BDI-FS appears to be particularly suitable as a screening instrument within the framework of primary health care. The use of the BDI-FS, for example for patients with pain disorders (Poole et al., 2009), in geriatric settings (Scheinthal et al., 2001), or for patients with multiple sclerosis (Benedict et al., 2003), is already explicitly recommended. Since high rates of underlying somatic diseases can also be found in the general population, the use of the BDI-FS seems also to be meaningful within this framework, especially when, due to a lack of time or for reasons of cost, no face-to-face interviews can be held. The applicability of the German BDI-FS to the variety of other patients who have been studied in different countries needs to be established in future research. Role of funding source Nothing declared. Conflict of interest No conflict declared. Acknowledgments The study was authorized by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Leipzig (Az.092–12-05032012). The study was financed by internal funds of the Department for Medical Psychology and Medical Sociology of the University Clinic of Leipzig. Appendix. Supplementary material Supplementary data associated with this article can be found in the online version at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.11.024. References Aromaa, E., Tolvanen, A., Tuulari, J., Wahlbeck, K., 2011. Personal stigma and use of mental health services among people with depression in a general population in Finland. BMC Psychiatry 11, 52. Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., Brown, G.K., 1996. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory. The Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX. Beck, A.T., Guth, D., Steer, R.A., Ball, R., 1997. Screening for major depression disorders in medical inpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory for Primary Care. Behav. Res. Ther. 35, 785–791. Beck, A.T., Steer, R.A., Brown, G.K., 2000. BDI-Fast Screen for Medical Patients: Manual. Psychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX. Benedict, R.H., Fishman, I., McClellan, M., Bakshi, R., Weinstock-Guttman, B., 2003. Validity of the beck depression inventory-fast screen in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. 9, 393–396. 239 Bracken, B.A., Barona, A., 1991. State of the art procedures for translating, validating and using psychoeducational tests in cross-cultural assessment. Sch. Psychol. Int. 12, 119–132. Chen, F.F., 2007. Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. 14, 464–504. DiStefano, C., Hess, B., 2005. Using confirmatory factor analysis for construct validation: an empirical review. J. Psychoedu. Assess. 23, 225–241. Dumenci, L., Achenbach, T.M., 2008. Effects of estimation methods on making traitlevel inferences from ordered categorical items for assessing psychopathology. Psychol. Assess. 20, 55. Flora, D.B., Curran, P.J., 2004. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychol. Methods 9, 466. Gierk, B., Kohlmann, S., Kroenke, K., Spangenberg, L., Zenger, M., Brähler, E., Löwe, B., 2013. The Somatic Symptom Scale–8 (SSS-8). A brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern. Med. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed. 2013.12179. Gilbody, S., Richards, D., Barkham, M., 2007. Diagnosing depression in primary care using self-completed instruments: UK validation of PHQ-9 and CORE-OM. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 57, 650–652. Hautzinger, M., Keller, F., Kühner, C., 2009. Beck-Depressions-Inventar: BDI-II; Manual [Beck Depression-Inventory: BDI II; Manual], 2end ed., Pearson Assessment, Frankfurt am Main. Hu, L.t., Bentler, P.M., 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ. Model.: Multidiscip. J. 6, 1–55. Kliem, S., Brähler, E., 2013. Beck Depressions-Inventar – Fast Screen (BDI-FS) deutsche Bearbeitung [Beck Depression-Inventory – Fast Screen Manual], 1st ed. Pearson Assessment, Frankfurt am Main. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., 2002. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 32, 1–7. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B., 2001. The PHQ‐9. Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 16, 606–613. Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B., Löwe, B., 2009. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics 50, 613–621. Löwe, B., Wahl, I., Rose, M., Spitzer, C., Glaesmer, H., Wingenfeld, K., Schneider, A., Brähler, E., 2010. A 4-item measure of depression and anxiety: validation and standardization of the Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4) in the general population. J. Affect. Disord. 122, 86–95. Lubke, G.H., Muthén, B.O., 2004. Applying multigroup confirmatory factor models for continuous outcomes to Likert scale data complicates meaningful group comparisons. Struct. Equ. Model. 11, 514–534. Meng, X.-L., Rosenthal, R., Rubin, D.B., 1992. Comparing correlated correlation coefficients. Psychol. Bull. 111, 172. Meredith, W., Teresi, J.A., 2006. An essay on measurement and factorial invariance. Med. Care 44, S69–S77. Millsap, R.E., Kwok, O.-M., 2004. Evaluating the impact of partial factorial invariance on selection in two populations. Psychol. Methods 9, 93. Mitchell, A.J., Lord, K., Symonds, P., 2012. Which symptoms are indicative of DSMIV depression in cancer settings? An analysis of the diagnostic significance of somatic and non-somatic symptoms. J. Affect. Disord. 138, 137–148. Nan, H., Lee, P.H., McDowell, I., Ni, M.Y., Stewart, S.M., Lam, T.H., 2012. Depressive symptoms in people with chronic physical conditions: prevalence and risk factors in a Hong Kong community sample. BMC Psychiatry 12. Poole, H., Bramwell, R., Murphy, P., 2009. The utility of the Beck Depression Inventory Fast Screen (BDI-FS) in a pain clinic population. Eur. J. Pain 13, 865–869. Pornprasertmanit, S., Miller, P., Schoemann, A., 2013. SemTools: Useful Tools for Structural Equation Modeling. R Package Available on CRAN. Radloff, L.S., 1977. The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl. Psychol. Meas. 1, 385–401. Rosseel, Y., Oberski, D., Byrnes, J., 2011. Lavaan: Latent Variable Analysis. R Package Version 0.4-11. Scheinthal, S., Steer, R., Giffin, L., Beck, A., 2001. Evaluating geriatric medical outpatients with the Beck Depression Inventory-Fastscreen for medical patients. Aging Ment. Health 5, 143–148. Strober, L., Arnett, P., 2010. Assessment of depression in multiple sclerosis: development of a “trunk and branch” model. Clin. Neuropsychol. 24, 1146–1166. Zigmond, A.S., Snaith, R.P., 1983. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 67, 361–370.