- Ninguna Categoria

Gender, Poverty, and Social Inclusion: Stream Readings

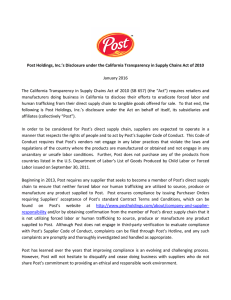

Anuncio