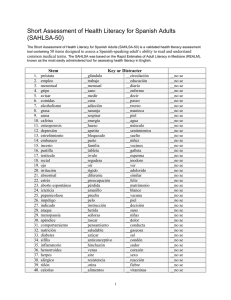

Accelerat ing t he world's research. jurnal american phychology asosiation tentang motivasi st. khusnul chotimah Related papers Download a PDF Pack of t he best relat ed papers Relat ionships among Fourt h Graders' Reading Anxiet y, Reading Fluency, Reading Mot ivat ion, a… Zuhal Çelikt ürk Sezgin Makale Hakkında Zuhal Çelikt ürk Sezgin Ort aokul Öğrencilerinin Okumaya İlişkin Kaygı ve Tut umlarının Okuma Alışkanlığı Üzerindeki Et kisi: Bir Y… Yasemin Baki Journal of Educational Psychology 2010, Vol. 102, No. 4, 773–785 © 2010 American Psychological Association 0022-0663/10/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0020084 Intrinsic and Extrinsic Reading Motivation as Predictors of Reading Literacy: A Longitudinal Study Michael Becker Nele McElvany Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, and Technical University, Dortmund Marthe Kortenbruck Free University, Berlin The purpose in this study was to examine the longitudinal relationships of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation with reading literacy development. In particular, the authors (a) investigated reading amount as mediator between motivation and reading literacy and (b) probed for bidirectional relationships between reading motivation and reading literacy, controlling for previous reading literacy. A total of 740 students participated in a longitudinal assessment starting in Grade 3, with further points of measurement in Grades 4 and 6. Structural equation models with latent variables showed that the relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and later reading literacy was mediated by reading amount but not when previous reading literacy was included in the model. A bidirectional relationship was found between extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy: Grade 3 reading literacy negatively predicted extrinsic reading motivation in Grade 4, which in turn negatively predicted reading literacy in Grade 6. Implications for research and practice are discussed. Keywords: reading literacy, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, reading frequency, elementary school In 2000, the International Reading Association published a position statement that listed “the development and maintenance of a motivation to read” as one of the key prerequisites for deriving meaning from print (International Reading Association, 2000). This statement illustrates the growing acknowledgment of the importance of reading motivation in research and practice in the last two decades. However, more than half of the Grade 4 students assessed in a recent U.S. national survey stated that reading was not their favorite activity and that they did not read frequently for enjoyment (Donahue, Daane, & Yin, 2005). The 2006 Progress in International Reading Literacy Study reported generally positive attitudes toward reading among Grade 4 students, but 37% of participating students stated that they read only once or twice a month or less (Mullis, Martin, Kennedy, & Foy, 2007). These results are particularly alarming in light of the recent research identifying reading motivation and reading amount as important predictors of reading literacy (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; Taboada, Tonks, Wigfield, & Guthrie, 2009). One of the fundamental distinctions in motivational research is between extrinsic and intrinsic motivation (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wigfield, Eccles, Schiefele, Roeser, & Davis-Kean, 2006). To date, however, reading research has focused primarily on the role of intrinsic reading motivation. Empirical findings show that mediating variables, such as reading amount, help to shape the influence of intrinsic motivation, but it remains unclear whether the same holds for extrinsic motivation (e.g., Guthrie, Wigfield, Metsala, & Cox, 1999). There is thus a need for longitudinal investigations covering both intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation to examine mediator variables that might help to explain the relations observed between motivation and achievement. This study is meant to advance scientific understanding of these issues by examining the complex relationships among intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, reading amount, and reading literacy from a longitudinal perspective. This article was published Online First October 11, 2010. Michael Becker, Center for Educational Research, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany; Nele McElvany, Center for Educational Research, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany, and Institute for School Development Research, Department of Education and Sociology, Technical University, Dortmund, Germany; Marthe Kortenbruck, Department of Education and Psychology, Free University, Berlin, Germany. We are grateful to Jürgen Baumert for providing the opportunity to realize the Berlin Longitudinal Reading Study and Cordula Artelt for advice for implementing this project. We also thank Susannah Goss for editorial assistance. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Michael Becker, Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Center for Educational Research, Lentzeallee 94, 14195 Berlin, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] Reading Literacy It is widely acknowledged that the success of a modern society is dependent on the level of literacy of its population. In its Programme for International Student Assessment, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development defined reading literacy as the ability “to understand, use and reflect on written 773 BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK 774 texts in order to achieve one’s goals, to develop one’s knowledge and potential, and to participate effectively in society” (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2001, p. 21). However, learning to read is a lengthy and complex process requiring psycholinguistic, perceptual, cognitive, and social skills (Gee, 2001; Snow, 2002). Beyond the basic acquisition of the alphabetic system (i.e., letter–sound correspondences and spelling patterns), reading expertise implies decoding, vocabulary knowledge, and text comprehension. Decoding skills are an essential part of reading fluency, defined as the ability to read a text accurately, quickly, and with proper expression (e.g., Fuchs, Fuchs, Hosp, & Jenkins, 2001) and are crucial for proficient reading (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [NICHD], 2000; Verhoeven & Van Leeuwe, 2008). Vocabulary has also been shown to be a critical predictor of reading comprehension; indeed, vocabulary acquisition and development of reading literacy are interlinked (Aarnoutse & van Leeuwe, 1998; Baker, Simmons, & Kameenui, 1995; Nagy, 1988; NICHD, 2000). Text comprehension is often conceived of as the “essence of reading” (Durkin, 1993). According to Kintsch (1998), text comprehension can be seen as a combination of text-based processes that integrate previous knowledge to a mental representation of the text. It is thus a form of cognitive construction in which the individual takes an active role. Text comprehension entails deep-level problem-solving processes that enable readers to construct meaning from text and derives from the (intentional) interaction between reader and text (Duke & Pearson, 2002; Durkin, 1993). When children begin learning to read systematically in school, the emphasis is initially on the acquisition of word-recognition skills. Relative to languages with deep orthographies, German has a regular orthography, and most readers in the German-speaking countries progress from the alphabetic to the orthographic stage of reading in their third year of schooling (Klicpera & GasteigerKlicpera, 1993; Seymour, Aro, & Erskine, 2003). In the subsequent years, the focus shifts to more complex aspects of the reading and comprehension processes— especially fluency, vocabulary knowledge, and text comprehension (Snow, Scarborough, & Burns, 1999). Besides social and institutional variables, strong influences on these processes include individual cognitive, motivational, and volitional factors. As outlined above, reading motivation has been identified as a key predictor of reading literacy in theoretical models and empirical research (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000; McElvany, Kortenbruck, & Becker, 2008; NICHD, 2000). Reading Motivation Reading motivation can be defined as “the individual’s personal goals, values, and beliefs with regard to the topics, processes, and outcomes of reading” (Guthrie & Wigfield, 2000, p. 405). The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is fundamental in motivation theory (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wigfield et al., 2006). Sources of intrinsic reading motivation include positive experience of the activity of reading itself, books valued as a source of enjoyment, the personal importance of reading, and interest in the topic covered by the reading material. Therefore, Guthrie and Wigfield (2000) defined intrinsic reading motivation as the disposition to read purely for the enjoyment, interest, and excitement of reading. In this sense, reading is performed for no sake but its own reward, and the activity is accompanied by positive emotions and perceived as highly satisfying (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Taboada et al., 2009). Extrinsically motivated reading, in contrast, is directed toward obtaining external recognition, rewards, or incentives (e.g., attention from parents or teachers, good grades; Deci & Ryan, 1985; Wang & Guthrie, 2004), toward living up to external expectations, or toward avoiding punishment (Hidi, 2000). External sources of influence on extrinsic reading motivation may vary depending on the age group—younger children are influenced primarily by their parents, whereas older children are also influenced by school and peers—and the role of instrumental motives may differ also. Reading Literacy and Reading Motivation Theoretical models and empirical research underline the importance of motivational variables for reading literacy. The goodinformation-processing model of Pressley, Borkowski, and Schneider (1989) integrates cognitive capacity, general strategies, metacognition, previous knowledge, and motivation. Deci and Ryan (1985) postulated a stronger need for competence and selfdetermination in intrinsically motivated activities, leading to higher performance in those activities (in this case, reading). At the same time, it has been argued that higher reading skills affect motivational beliefs (Morgan & Fuchs, 2007). Several empirical studies have examined the relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy and usually have found a moderate positive association (Baker & Wigfield, 1999; Guthrie et al., 1999; Taboada et al., 2009; Unrau & Schlackman, 2006; for Germany, see McElvany et al., 2008; Schaffner & Schiefele, 2007). Guthrie et al. (1999) found that reading motivation still explained a significant amount of the variance in text comprehension among Grade 10 students when controlling for covariates such as past achievement, amount of reading, reading efficacy, and socioeconomic status. In a study with elementary school children, Taboada et al. (2009) found that internal motivation and cognitive processes (e.g., background knowledge, selfgenerated questions) made significant independent contributions to variance in reading comprehension and in fact explained the equivalent of 3 months’ growth in reading comprehension. In evaluations of their intervention program CORI (Concept Oriented Reading Instruction; Guthrie et al., 2004), which was designed to enhance reading comprehension, intrinsic reading motivation, and strategic knowledge, the researchers led by Guthrie and Wigfield found the promotion of intrinsic reading motivation to be associated with an increase in reading comprehension. Fewer longitudinal studies have referred specifically to intrinsic reading motivation. However, Gottfried, Fleming, and Gottfried (2001) reported a significant positive relationship between intrinsic reading motivation at a young age (7 years) and later reading achievement (8 and 9 years). (For a review of studies investigating the relationship between children’s reading and children’s competency beliefs and goal orientations, see Morgan & Fuchs, 2007.) There has been scarce empirical coverage of the relationship between extrinsic reading motivation and reading processes. Additionally, as mentioned above, the sources of extrinsic motivation differ with age. Parents are typically still the most important social INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION influence for elementary school students, whereas peers have increasing influence at secondary level. The available results tend to indicate a negative relationship, with high extrinsic motivation being related to poorer reading skills (Schaffner & Schiefele, 2007; Unrau & Schlackman, 2006; Wang & Guthrie, 2004). In their review of seven reading programs, Gear, Wizniak, and Cameron (2004) examined whether incentive systems for students facilitate or hinder learning and motivation. Their findings suggest that rewards can have positive effects on intrinsic motivation and performance under certain conditions (e.g., when the reward involves spontaneous and sincere positive feedback and when students are rewarded frequently and immediately after successful performances). The precise nature of the relationship between extrinsic motivation and reading literacy thus remains unclear; further research in this domain is clearly warranted. Research on mediating variables that may influence the relationship between motivational and cognitive processes in the reading context has taken two main approaches. First, the effects of reading motivation on strategy use and deeper level comprehension processes have been examined; the results of this research approach are inconsistent (e.g., Naceur & Schiefele, 2005). A second, possibly more promising approach has investigated reading behavior, in terms of reading amount, as a mediator of the correlation between reading motivation and text comprehension. 775 (1999) found that both intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation correlated significantly with total reading amount, explaining 10.7% and 12.4% of the variance, respectively. These results led Wang and Guthrie (2004) to formulate a theoretical model that proposes a functional chain, in which reading motivation increases reading amount, which in turn increases reading literacy. As expected, their empirical findings showed a negative association between extrinsic reading motivation and reading achievement and a positive association between intrinsic reading motivation and reading achievement. However, inconsistent with previous findings, reading amount did not mediate the relationship of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation with reading achievement. This pattern of results may be attributable to the cross-sectional design of the study. Previous studies have also postulated reciprocal relationships among reading motivation, reading behavior, and reading literacy (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997; McElvany et al., 2008; Morgan & Fuchs, 2007). However, cross-sectional designs cannot disentangle the reciprocal patterns of influence between different constructs. There is a clear need for longitudinal research to further elucidate the relationships between the reading-related constructs from a developmental perspective, their potential mediators, and the role of prior achievement. Purpose in the Present Study Reading Amount Guthrie et al. (1999) discussed several mechanisms theoretically proposed to underlie the potential mediating role of reading amount. First, more frequent reading might enhance reading efficiency, as reading processes become better automatized. Increased decoding and strategy use might free up more cognitive resources for higher order information processing, leading to better comprehension. A second plausible explanation is that frequent reading leads to an increase in students’ prior knowledge. This facilitates comprehension on the text-based level and hence the construction of the situational model (Kintsch, 1998). A third explanation is that frequent reading supports reading self-concept and self-efficacy beliefs, leading to the selection of more difficult texts. Fourth, it is conceivable that the attunement of cognitive and motivational goals leads to automatized and habitualized processes. Several studies have reported links between reading behavior and reading achievement. Cipielewski and Stanovich (1992) showed that, even when controlling for cognitive abilities, children who read in their leisure time outperformed their peers on a reading achievement test. Anderson, Wilson, and Fielding (1988) found the time children spend reading outside school to be the best predictor of growth in school reading achievement between Grades 2 and 5 (see also Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997; Taylor, Frye, & Maruyama, 1990, for an experimental study design). The more recent 2003 National Assessment of Educational Progress report found that children who read more understand texts better than those who read less (Donahue et al., 2005). In studies investigating the relationship between reading motivation and reading amount, highly motivated children have been found to read more frequently than less motivated children. For example, Wigfield and Guthrie (1997) found reading amount to be predicted by reading motivation in Grade 4 and 5 students. In a second study with elementary school children, Guthrie et al. This study makes three key contributions to the emerging literature on reading motivation. It examines, from a longitudinal perspective, how reading amount and reading literacy are associated, first, with intrinsic reading motivation and, second, with extrinsic reading motivation. Third, it probes for bidirectional relationships between reading motivation and reading literacy, taking the effects of previous reading achievement into account. Our first research aim concerns the relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy. As outlined above, previous research indicates a positive relationship between intrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy. Going one step further, we hypothesized that Grade 4 intrinsic motivation would positively predict Grade 6 reading literacy (Research Aim 1.1) and that this association would be mediated by Grade 4 reading amount (Research Aim 1.2). By analogy, the second research aim concerns the relationship between extrinsic motivation and reading literacy. Previous findings on this relationship are inconsistent (see above). We therefore explored the nature of the relationship between Grade 4 extrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy (Research Aim 2.1). Furthermore, we analyzed whether a mediating effect of reading amount can indeed be detected for extrinsic motivation. It is conceivable that extrinsically motivated children also read more frequently, with corresponding effects on their reading literacy (Research Aim 2.2). Our third research aim was to integrate previous reading literacy within an extended theoretical model and to probe for bidirectional relationships of reading literacy with intrinsic/extrinsic motivation (see Morgan & Fuchs, 2007). We hypothesized that Grade 4 reading motivation would be influenced by Grade 3 reading literacy (Research Aim 3.1). Finally, we investigated whether the effects of intrinsic/extrinsic reading motivation and Grade 4 reading amount on Grade 6 reading literacy would persist when Grade BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK 776 3 reading literacy was included as predictor of all constructs in the model (Research Aim 3.2). Method Participants and Design A total of 740 students from 54 classes in 22 Berlin elementary schools participated in the longitudinal study. The average age at the end of Grade 3 was just over 9 years (M ⫽ 9.1 years, SD ⫽ 0.5). Boys were slightly in the majority (53%). Data on students’ family background showed that 71% lived in two-parent homes; 63% spoke only German at home, whereas 37% either used German and another language or spoke only another language within the family. One of the criteria for the selection of the participating schools was their location in various districts of Berlin, which ensured a mix of social backgrounds. Data were collected within the framework of the Berlin Longitudinal Reading Study LESEN 3– 6, which was conducted by the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin, Germany. The main purpose in the study was to track children’s reading development from Grade 3 to Grade 6 and to identify individual, social, and institutional factors influencing this development. A subsample of 104 students participated in a family-based reading intervention program between Grades 3 and 4 (McElvany, 2008; McElvany & Artelt, 2009).1 The data analyzed in the following were collected in three waves: at the end of Grade 3 in June 2003 (T1), in the middle of Grade 4 in January 2004 (T2), and at the end of Grade 6 in May 2006 (T3). In all three waves, students were assessed in classrooms during regular school hours by trained experimenters. Most students in Berlin transfer to secondary schooling after 6 years of elementary education. However, some students of the students in our sample (N ⫽ 55) transferred to secondary school after Grade 4. These students, and students who were absent for the in-school assessment, were tested at the Max Planck Institute. Another subset of the sample (N ⫽ 45) was assessed at the institute under the same conditions on all measurement occasions. Measures Reading literacy. Reading literacy, as all other variables used in the following analyses, was operationalized as a latent variable (see below for technical procedures). Three indicators of processes of different complexity were used to specify the factor of reading literacy, namely, text comprehension, vocabulary, and decoding. Grade 3 text comprehension was assessed with a sample of texts with multiple-choice questions from the Hamburger Lesetest (HAMLET 3– 4; Lehmann, Peek, & Poerschke, 1997). In Grade 6, texts from the Diagnostischer Test Deutsch (Nauck & Otte, 1980) were applied. Texts and tasks with different item difficulties were selected to cover a broad spectrum of ability. Tasks ranged in complexity from simple comprehension questions to more complex questions requiring inferential comprehension. A set of 15 items from the CFT vocabulary test (German version; Weiss, 1987) assessed students’ Grade 3 vocabulary. This test covers basic and colloquial vocabulary from key areas of life and does not require any special knowledge. Grade 6 vocabulary was assessed with the vocabulary subtest of the Kognitiver Fä- higkeitstest (Heller & Perleth, 2000), which is analogous in structure to the CFT. Rasch analysis was used to create two ability scales, one for text comprehension and one for vocabulary. The items were linked through external calibration samples and fitted a one-dimensional Rasch model. Item parameters were estimated based on these samples. Given the good fit of the Rasch model, measurement equivalence can be assumed (Kolen & Brennan, 2004). The reliabilities of the tests across the two waves of assessment range from good to satisfactory (text comprehension, Cronbach’s ␣t1 ⫽ .78, ␣t2 ⫽ .69; vocabulary, Cronbach’s ␣t1 ⫽ .69, ␣t2 ⫽ .78). Decoding was evaluated with a speeded 70-item multiple-choice test (Würzburger Leise Leseprobe [Würzburg Silent Reading Test]; Küspert & Schneider, 1998) that required one of four pictures to be matched to a given word (e.g., foot or thermometer). Correct answers were coded as 1; incorrect answers or unchecked answers were coded as 0. A sum score with a maximum of 70 points was then computed. Different item sets were administered at pre- and posttest. For test security reasons, two versions of each test, differing only in the order of the items, were used at each point of measurement. Intrinsic reading motivation. The measures of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation administered were based on our previous work but were expanded for this study (McElvany, 2008; McElvany, Becker, & Lüdtke, 2009; McElvany et al., 2008). Intrinsic reading motivation at Grade 4 was measured with three factors, each with one to four indicators. Four items, three of which were positively phrased (“I like reading,” “Reading is fun,” “I read because I like reading stories”) and one of which was negatively phrased (“I think reading is boring”), assessed the intrinsic value attached to the activity of reading. Students rated their agreement with the items on a 4-point Likert scale (1 ⫽ disagree completely to 4 ⫽ agree completely). The scale had a high reliability (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .89). Two additional items tapped the intrinsic value attached to books (“I am pleased when I get a new book to read,” “When my parents give me a book as present, I am interested in it”). Cronbach’s ␣ was acceptable at .63. Last, importance of reading was measured with a single-item indicator (“I prefer watching television to reading”). Extrinsic reading motivation. Extrinsic motivation to read was also measured with three factors: Extrinsic motivation provided by parents was assessed with three unipolar items (“I read because my parents find it important that I read a lot,” “I read because my parents want me to,” “I read because I want my parents to be proud of me”). Responses were given on a 4-point Likert scale (1 ⫽ disagree completely to 4 ⫽ agree completely). The reliability of the scale was good (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .78). Extrinsic motivation provided by school was measured with a single indicator: “I read because I have to read for school.” Finally, extrinsic motivation resulting from instrumental goals was measured with three items (“I read because it is important in life to be 1 Participation in the reading program (RP) and early transfer to secondary school (Gy) were also controlled for in statistical analyses: The variables were included in the models as predictors for the constructs in Grades 4 (RP) and 6 (RP, Gy). The pattern of results was consistent with that presented here. For reasons of clarity, the models are therefore presented without the control variables in the present article. INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION a good reader,” “I read because I can learn a lot through reading,” “I read because it is important to me to know a lot”). The scale displayed good reliability (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .77). Reading amount. Reading amount was assessed through student self-reports and parent questionnaires and measured with three factors, each with one or two indicators of reading length/ reading frequency: Reading length (student assessment) was measured with the question “How long do you usually read each day?” Reading length (parent assessment) was assessed with two questions “On average, how many hours does your child read outside school on a weekday?”/“. . . on a weekend day?” The response categories for these items were as follows: 1 ⫽ not at all, 2 ⫽ less than half an hour, 3 ⫽ 30 to 60 minutes, 4 ⫽ 1 to 2 hours, 5 ⫽ more than 2 hours. Reliability was acceptable (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .69). Reading frequency was tapped with two items in the student questionnaire (“How often do you read for pleasure?” and “Do you read during the school holidays?”). Students rated the frequency of their reading on a 5-point Likert scale (response options 1 ⫽ never, 2 ⫽ rarely, 3 ⫽ sometimes, 4 ⫽ often, and 5 ⫽ always). Reliability was adequate (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .82). Statistical Analyses All statistical analyses were conducted with SPSS 15 and Mplus Version 5.1. We assumed that a single dimension (reading literacy) underlies the three facets of text comprehension, decoding, and vocabulary and thus expected these facets to load highly on one factor. Exploratory factor analysis was used to test the unidimensionality of the latent variable reading literacy. The factor loadings of reading literacy in Grades 3 and 6 were specified to be equal in the models to ensure measurement invariance across time. Exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis was used to examine the underlying factor structure of the items designed to measure intrinsic reading motivation, extrinsic reading motivation, and reading amount. The parameters of the factor loadings were specified to be free. All of the following models were computed with Mplus 5.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998 –2008) using the type ⫽ general option. We considered using the type ⫽ complex option, but problems occurred in the computational process.2 As the main findings were comparable in the two types of model specification, we relied on the conventional error estimation. We tested the hypotheses using structural equation modeling. The fit of the models tested was evaluated on the basis of two goodness-of-fit indices: the comparative fit index (CFI) and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Acceptable model fit is indicated by CFI values greater than .95 and RMSEA values of .05 or less. The chi-square difference test was used to compare the fit of the nested models (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Bootstrapping was used to test the indirect, mediating effect of reading amount. Bootstrapping has become the most widespread method for testing mediation, as it does not require the normality assumption. If the bootstrap confidence interval does not include zero, there is a 95% probability that the indirect effect is significant (Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Missing Data Incomplete data often present a challenge in longitudinal research. It is not unusual for participants to be absent at one or more 777 points of measurement or to drop out of a study completely. In order to avoid reduction of sample size or biased results, and to capitalize on all of the information available, we chose the full information maximum likelihood estimation option in Mplus for the analyses. This option allowed us to include participants with partially missing values. All main variables (text comprehension, vocabulary, decoding, intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, reading amount) were examined for systematic dropout. In general, the marginal differences were not statistically significant. Hence, nonsystematic dropout can be assumed for these variables (Kortenbruck, 2007). Results Descriptive Statistics Table 1 presents intercorrelations between the latent variables. As expected, there were high intercorrelations among achievement variables as well as among motivational/behavioral variables and lower intercorrelations across the construct areas. For example, Grade 3 reading literacy correlated more closely with Grade 6 reading literacy than it did with the three latent indicators of intrinsic reading motivation at Grade 4 (see also Table 2). Confirmatory factor analyses revealed that reading literacy in Grade 3 and 6 can be represented by two factors, one for each measurement point. Model fit was still satisfactory when the factor loadings were set to be invariant, 2(8) ⫽ 41.84, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .97, RMSEA ⫽ .07, with residuals correlated for vocabulary and decoding. In terms of construct validity, as expected, separate confirmatory factor analyses for intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and reading amount confirmed that the expected factor structure—with three first-order factors as indicators of each construct—fit the data well: intrinsic motivation, 2(12) ⫽ 50.74, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .98, RMSEA ⫽ .08; extrinsic motivation, 2(12) ⫽ 79.45, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .95, RMSEA ⫽ .09; reading amount, 2(3) ⫽ 10.06, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .99, RMSEA ⫽ .06. Additionally, an overall confirmatory factor analysis for the second-order factor structure confirmed that a three-factor model, 2(143) ⫽ 510.13, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .92, RMSEA ⫽ .07, fit the data better than a two-factor model combining intrinsic and extrinsic motivation to form a single factor, 2(145) ⫽ 707.145, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .88, RMSEA ⫽ .08. Likewise, other two-factor solutions and the one-factor solution had a statistically significantly poorer fit: reading amount combined with intrinsic motivation, 2(146) ⫽ 542.71, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .91, RMSEA ⫽ .07; reading amount combined with extrinsic motivation, 2(145) ⫽ 720.49, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .87, RMSEA ⫽ .08; one-factor model, 2(146) ⫽ 742.23, p ⬍ .05, 2 The type ⫽ complex option would in general be the more desirable estimation method because it corrects for the standard errors resulting from the hierarchical data structure: Students are nested within classes and are therefore not randomly chosen. As there are more degrees of freedom (157) than clusters (N ⫽ 50) in the models, there is no guarantee that the estimation of the model parameters is trustworthy (http://www.statmodel.com/discussion/messages/12/164.html? 1191440281). However, the pattern of results emerging when the type ⫽ complex option was applied was consistent with that emerging when the type ⫽ general option was applied. BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK 778 Table 1 Descriptive Statistics: Correlations Between the First Order Latent Variables Correlations Variable 1 Reading literacy 1. Reading literacy (Grade 3) 2. Reading literacy (Grade 6) Intrinsic motivation 3. Value of reading 1, activity (Grade 4) 4. Value of reading 2, books (Grade 4) 5. Importance of reading (Grade 4) Extrinsic motivation 6. Extrinsic motivation through parents (Grade 4) 7. Extrinsic motivation through school (Grade 4) 8. Instrumental motivation (Grade 4) Reading amount 9. Reading frequency (student report; Grade 4) 10. Reading length (student report; Grade 4) 11. Reading length (parent report; Grade 4) ⴱ p ⬍ .05. ⴱⴱ p ⬍ .01. ⴱⴱⴱ 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 — .90ⴱⴱⴱ — .36ⴱⴱⴱ .36ⴱⴱⴱ ⴱⴱⴱ .24 .23 ⴱⴱⴱ .78ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.17ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.24ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.50ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.42ⴱⴱⴱ — ⫺.47ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.57ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.15ⴱⴱ ⫺.01 .13ⴱⴱ — ⫺.45ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.51ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.21ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.05 .17ⴱⴱⴱ .56ⴱⴱⴱ — ⫺.12ⴱ ⫺.26ⴱⴱⴱ .37ⴱⴱⴱ .41ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.18ⴱⴱⴱ .57ⴱⴱⴱ .35ⴱⴱⴱ .37ⴱⴱⴱ .47ⴱⴱⴱ .72ⴱⴱⴱ .66ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.49ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.18ⴱⴱ .18ⴱⴱⴱ .13ⴱ .48ⴱⴱⴱ .46ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.28ⴱⴱⴱ .02 ⴱⴱⴱ ⴱⴱⴱ ⴱⴱⴱ ⴱⴱⴱ .47 .44 .38 ⫺.29 ⴱⴱ ⫺.18 — ⫺.25ⴱⴱⴱ .26ⴱⴱⴱ — ⫺.05 .27ⴱⴱⴱ .56ⴱⴱⴱ ⴱ ⴱⴱⴱ .10 ⫺.14 .63 — .45ⴱⴱⴱ — p ⬍ .001. Intrinsic Reading Motivation and Comprehension We used structural equation modeling to test the extent to which Grade 6 reading literacy can be predicted by Grade 4 intrinsic motivation and whether this relationship is mediated by Grade 4 reading amount. We expected, based on our hypotheses, that motivation would predict reading amount and that increased reading amount would predict higher reading literacy. Two models were estimated. The first model specified the association between Grade 4 intrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy. The model fit can be considered as good, 2(32) ⫽ 81.67, p ⬍ .05, CFI ⫽ .98, RMSEA ⫽ .05. Consistent with the hypothesis formulated with respect to Research Aim 1.1, Grade 6 reading literacy was positively predicted by Grade 4 intrinsic motivation ( ⫽ .32, p ⬍ .001). The second model additionally took into account Grade 4 reading amount (see Figure 1). Model fit can be regarded as good, 2(83) ⫽ 188.11, p ⬍ .001, CFI ⫽ .97, RMSEA ⫽ .04. When Grade 4 reading amount was controlled for, the association between Grade 4 intrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy was no longer statistically significant ( ⫽ ⫺.07, p ⫽ .73). However, Grade 4 intrinsic motivation and reading amount were highly correlated ( ⫽ .85, p ⬍ .001), and Grade 6 reading literacy was statistically significantly predicted by Grade 4 reading amount ( ⫽ .46, p ⬍ .05). The mediating effect of reading amount on the Table 2 Descriptive Statistics: Correlations Between the Latent First and Second Order Variables (First Order Factors for Reading Literacy Grade 3 and 6; Second Order Factors for Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation and Reading Amount) Correlations Variable † 11 — CFI ⫽ .87, RMSEA ⫽ .08. Hence, the following analyses are based on a three-factor model comprising intrinsic and extrinsic motivation as well as reading amount. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 10 — ⴱⴱⴱ .45 9 Reading literacy (Grade 3) Reading literacy (Grade 6) Intrinsic reading motivation (Grade 4) Extrinsic reading motivation (Grade 4) Reading amount (Grade 4) p ⬍ .10. ⴱ p ⬍ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⬍ .001. 1 2 — .90ⴱⴱⴱ .37ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.52ⴱⴱⴱ .41ⴱⴱⴱ — .38ⴱⴱⴱ ⫺.64ⴱⴱⴱ .43ⴱⴱⴱ 3 — ⫺.09† .85ⴱⴱⴱ 4 5 — ⫺.14ⴱ — INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION ε dt78 ε ε ε ε dt79 dt76 dt73 dt29 .92*** -.82*** .66*** .91*** im4val1 ε .55*** dt81 dt80 .84*** 1 im4imp im4val2 .83*** .91*** 779 -.55*** Intrinsic Motivation 4 -.07 .85*** .46* Amount 4 .93*** dt42 ε ε .56*** Decod 6 ε Vocab ε .67*** .85*** lv4dup lv4dust .85*** dt43 Literacy 6 .62*** lv4freq .82*** Comp 6 .68*** 1 dt95 .65*** .82*** deo1 deo2 ε ε ε Figure 1. Associations among intrinsic reading motivation (im), reading amount, and reading literacy (standardized path coefficients ). dt ⫽ items from student questionnaire; deo ⫽ items from parents’ questionnaire; lv ⫽ reading behavior; comp ⫽ comprehension; decod ⫽ decoding; vocab ⫽ vocabulary. 2(83) ⫽ 118.11, p ⬍ 2 2 .001, CFI ⫽ .97, RMSEA ⫽ .04, RLiteracy6 ⫽ .16, RAmount4 ⫽ .73. ⴱ p ⱕ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⱕ .001. association between reading literacy and intrinsic motivation was small but statistically significant ( ⫽ .39, BC bootstrap 95% CFI [.05, .73]). Hence, our findings supported the hypothesized mediating effect of Grade 4 reading amount (Research Aim 1.2). Extrinsic Reading Motivation and Comprehension We next estimated two analogous models to investigate how extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy are associated and whether their relationship is also mediated by reading amount. Again, we expected, based on our hypotheses, that motivation would predict reading amount and that increased reading amount would predict higher reading literacy. The first model specified the relationship between Grade 4 extrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy. Model fit can be regarded as good, 2(32) ⫽ 135.00, p ⬍ .001, CFI ⫽ .94, RMSEA ⫽ .07. Grade 6 reading literacy was found to be negatively predicted by Grade 4 extrinsic reading motivation ( ⫽ ⫺.59, p ⬍ .001; Research Aim 2.1). In the second model, Grade 4 reading amount was included in the analysis (see Figure 2; Research Aim 2.2). Model fit was good (see Figure 2 for details). The negative association between Grade 4 extrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy was still strong and statistically significant ( ⫽ ⫺.56, p ⬍ .001). However, Grade 6 reading literacy was also positively predicted by Grade 4 reading amount ( ⫽ .35, p ⬍ .001), and there was a small negative association between Grade 4 reading amount and Grade 4 extrinsic motivation ( ⫽ ⫺.12, p ⬍ .05). In particular, students with high extrinsic motivation reported lower amounts of reading in terms of both reading length and reading frequency. These students also showed lower reading literacy later on. The mediat- ing effect of reading amount on the association between reading literacy and extrinsic motivation was statistically significant ( ⫽ ⫺.04, BC bootstrap 95% CFI [⫺.08, ⫺.00]) but negligible in size. The negative direct effect of extrinsic reading motivation on reading literacy thus remained significant when we controlled for reading amount. The indirect effect of extrinsic reading motivation on reading literacy via reading amount was marginally statistically significant. This finding makes sense in light of the negative association of extrinsic motivation with both reading amount and reading literacy, as compared with the positive association between reading amount and reading literacy. In conclusion, extrinsic motivation was negatively associated with reading amount as well as with reading literacy, and reading amount did only weakly mediate the relationship between extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy (Research Aim 2.2). Is There a Bidirectional Relationship of Motivation and Reading Literacy? In the final step, previous reading literacy was included in the models. The goals in these analyses were twofold. First, we expected not only that reading literacy would be influenced by motivation but also that motivation would be influenced by reading literacy. Second, we expected that the mediator effect of reading amount would persist even when we controlled for previous reading literacy. As a mediator effect was found for intrinsic but not for extrinsic motivation, meaning that the potential effects of reading amount are attributable solely to intrinsic motivation, all variables were included in a single model (see Figure 3 and the Appendix). BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK 780 ε ε deo1 deo2 dt95 .85*** .64*** 1 lv4dup lv4dust .63*** .74*** ε ε dt42 dt43 .83*** .84*** lv4freq .68*** .89*** .34*** Amount 4 Literacy 6 .57*** Comp 6 ε Decod 6 ε Vocab 6 ε .83*** -.12* -.56*** Extrinsic Motivation 4 .92*** .62*** em4p .59*** em4sc em4ins .69*** .72*** .69*** .79*** 1 dt65 dt67 dt70 ε ε ε .79*** dt75 .71*** dt72 dt74 dt63 ε ε ε Figure 2. Associations among extrinsic reading motivation (em), reading amount, and reading literacy (standardized path coefficients ). dt ⫽ items from student questionnaire; deo ⫽ items from parents’ questionnaire; lv ⫽ reading behavior; comp ⫽ comprehension; decod ⫽ decoding; vocab ⫽ vocabulary. 2(83) ⫽ 2 2 298.80, p ⬍ .001, CFI ⫽ .92, RMSEA ⫽ .06, RLiteracy6 ⫽ .49, RAmount4 ⫽ .02. ⴱ p ⱕ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⱕ .001. The model fit can be considered good, 2(261) ⫽ 762.79, p ⬍ .001, CFI ⫽ .92, RMSEA ⫽ .05. The model explained a total of 86% of the variance in Grade 6 reading literacy. Consistent with the hypothesis formulated with respect to Research Aim 3.1, Grade 3 reading literacy positively predicted intrinsic motivation ( ⫽ .37, p ⬍ .001) and negatively predicted extrinsic motivation ( ⫽ ⫺.52, p ⬍ .001). Grade 3 reading literacy was also marginally statistically significantly associated with reading amount ( ⫽ .11, p ⫽ .08) and strongly predicted Grade 6 reading literacy ( ⫽ .74, p ⬍ .001). Intrinsic motivation still Intrinsic Motivation 4 .74*** .01 .37*** .14* Literacy 3 -.52*** .81*** .11† Amount 4 -.01 .09 Literacy 6 -.24*** Extrinsic Motivation 4 Figure 3. Associations among Grade 3 and Grade 6 reading literacy, Grade 4 intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation, and Grade 4 reading amount (standardized path coefficients ). 2(261) ⫽ 762.79, p ⬍ .05, 2 2 CFI ⫽ .92, RMSEA ⫽ .05, RLiteracy6 ⫽ .86, RIntrinsic Motivation4 ⫽ .14, 2 2 † RExtrinsic Motivation4 ⫽ .27, RAmount4 ⫽ .73. p ⬍ .10. ⴱ p ⱕ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⱕ .001. strongly predicted reading amount ( ⫽ .81, p ⬍ .001), but a statistically significant association between reading amount and later reading literacy was no longer found ( ⫽ .09, p ⫽ .50) when Grade reading 3 literacy was included in the model (Research Aim 3.2). When Grade 3 reading literacy was accounted for, the predictive association between Grade 4 extrinsic motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy persisted but was markedly weaker ( ⫽ ⫺.24, p ⬍ .001). Nevertheless, the overall pattern of results shows that students with lower reading literacy displayed higher levels of extrinsic motivation (e.g., reading to please their parents) in Grade 4 and that higher extrinsic motivation predicted lower reading literacy in Grade 6. To summarize, when we accounted for prior achievement, the correlations between intrinsic motivation, reading amount, and Grade 6 reading literacy were weaker and no longer significant. In contrast, Grade 3 achievement negatively predicted Grade 4 extrinsic motivation and strongly positively predicted Grade 6 reading literacy. The negative predictive effect of extrinsic motivation on later reading literacy persisted when prior achievement was controlled. Discussion Summary and Interpretation The research aims guiding this study were twofold. First, we examined the relationship between intrinsic/extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy, as well as the potential mediating effect of reading amount, from a longitudinal perspective. Second, we probed for bidirectional relationships of reading motivation and INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION reading achievement, investigating whether intrinsic/extrinsic reading motivation and reading amount not only influence reading literacy but are themselves predicted by previous reading achievement. Additionally, we examined the pattern of relations emerging among motivation, reading amount, and later achievement when controlling for prior achievement. Consistent with our hypotheses, the data confirmed that Grade 4 intrinsic reading motivation was positively related to Grade 6 reading literacy. This relationship was mediated by reading amount. In other words, children who see reading as a desirable activity tend to read more frequently and thus develop better reading skills (see also Guthrie et al., 1999). The initial relationship between Grade 4 intrinsic motivation and Grade 6 reading achievement was as high as that reported by Unrau and Schlackman (2006) but smaller than that reported by Wang and Guthrie (2004). However, a different picture emerged for extrinsic reading motivation, which was negatively correlated with reading literacy and was not found to be substantially mediated by reading amount. In other words, children who read for extrinsic reasons (e.g., parental pressure) have poorer reading skills than do children with lower extrinsic motivation. When previous reading literacy was taken into account, the pattern of relationships changed in some respects. Our findings indicate high stability of reading achievement from Grade 3 to Grade 6: Good readers in Grade 3 tend to still be good readers in Grade 6; poor readers in Grade 3 tend to still be comparatively poor readers in Grade 6. When past achievement was taken into account, the effect of intrinsic motivation mediated by reading amount was overshadowed by the direct effect of Grade 3 reading literacy on Grade 6 reading literacy (cf. the findings reported by Wang & Guthrie, 2004, who still found a significant relationship between motivation and achievement but using grades rather than test scores as indicators of prior achievement). One possible explanation for prior achievement attenuating the effect of motivation relates to the high stability of reading achievement, which has been confirmed by several longitudinal studies examining the development of reading achievement (e.g., Aarnoutse, van Leeuwe, Voeten, & Oud, 2001; Morgan, Farkas, & Hibel, 2008). Given this stability, little variance in achievement can be independently explained. Another explanation is that the earlier achievement measure also includes the variance associated with motivational aspects. Therefore, it cannot be strictly concluded from the present results that intrinsic motivation has no influence on reading literacy; the results rather speak against additional effects of intrinsic motivation when past achievement, confounded with intrinsic motivation, is taken into account. However, Grade 4 intrinsic reading motivation was strongly predicted by Grade 3 reading literacy. This association between past achievement and later motivation seems to indicate that individuals enjoy activities they are good at and are thus motivated to engage in them in the future. These findings are not entirely incompatible with the hypothesis of a bidirectional relationship (cf. Morgan and Fuchs, 2007, who concluded from their review study that there is a bidirectional relationship between reading motivation and reading literacy). Against the background of this discussion, the findings for extrinsic motivation are all the more remarkable: In contrast to intrinsic motivation, the negative relationship between Grade 4 extrinsic reading motivation and Grade 6 reading literacy weak- 781 ened, but remained statistically significant, when we controlled for Grade 3 reading literacy. Our findings confirmed the expected bidirectional relationship between extrinsic motivation and reading literacy: Grade 3 reading negatively predicted Grade 4 extrinsic motivation, which was negatively related to Grade 6 reading literacy, even when we controlled for Grade 3 reading literacy. Extrinsically motivated children read because they, for example, want to please their parents. The bidirectional relationship might imply that early reading failure leads to higher extrinsic motivation, with children reading only when they have to, which in turn leads to poorer reading skills. Morgan and Fuchs (2007) argued that these children avoid reading. However, our complex model supports this conclusion only to a certain degree: Initially, we indeed found a negative relationship between extrinsic reading motivation and reading amount, but this relationship did not remain statistically significant when we controlled for previous reading literacy in the more complex model. Therefore, it can be concluded that reading amount is strongly determined by the level of the individual’s intrinsic motivation (and, to a certain degree, by prior reading literacy) but that there is no significant additional effect of extrinsic reading motivation. The negative relationship between extrinsic reading motivation and reading literacy may also be explained by an inadequate focus on the text, resulting from ineffective strategies and inaccurate inferences (Wang & Guthrie, 2004). From this perspective, it is possible that extrinsically motivated readers use surface-level strategies, such as guessing and memorization, and fail to screen out nonsensical ideas (Elliott & Dweck, 1988; Pintrich & Schrauben, 1992). A complex picture emerges from our data: The paths from reading amount to later reading literacy just failed to reach statistical significance when prior reading literacy was included as a predictor in the model, underlining the importance of early competence for later development. Reading amount was strongly predicted by intrinsic reading motivation, which in turn was determined partly by early reading literacy. Additionally, the direct predictive value of early reading literacy for later reading amount corresponds with the long-term findings of Cunningham and Stanovich on reading development from Grade 1 to Grade 11. They concluded that rapid acquisition of reading ability might help children to develop a lifetime habit of reading (Cunningham & Stanovich, 1997, p. 934). Overall, the present empirical findings are well embedded in the framework guiding this research. The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is well established in motivational research (Deci & Ryan, 1985; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Wigfield et al., 2006). It has been suggested that intrinsically motivated children invest more time and effort to fully understand texts. As a result, they tend to achieve deeper levels of text comprehension (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie, 2000; Schiefele, 1999). Our analyses further substantiate the idea that reading amount (in terms of frequency and length of reading) is related to reading motivation and mediates the relationship between intrinsic motivation and achievement when motivation and previous reading literacy are controlled. Still, there appear to be differences in how the relationship between motivation and achievement is established and mediated: Distinct relationships and processes seem to underlie intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the context of reading. The finding that the two types of motivation have differential implications for behavior is in line 782 BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK with results reported by Wang and Guthrie (2004) on the basis of a cross-sectional sample. Our finding of a statistically significant negative effect of extrinsic motivation on later achievement with no concurrent positive effect of intrinsic motivation further informs the discussion about different forms of motivation and the potential corruption of intrinsic by extrinsic motivation (Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999; Higgins, Lee, Kwon, & Trope, 1995). At the same time, the results have important implications for educators and parents, in terms of the importance of avoiding measures that support students’ extrinsic rather than intrinsic reading motivation (Gottfried et al., 2001). Our findings thus confirm that the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is both valid for practice and useful for reading research. Strengths, Limitations, and Outlook The present study has important theoretical, methodological, and statistical strengths. Both intrinsic and extrinsic reading motivation were examined. Reading literacy was not specified solely in terms of text comprehension but as a multifaceted construct with vocabulary and decoding as additional indicators of reading achievement. The latent longitudinal design was a clear statistical strength. Not only were students examined at three points of measurement but all variables were estimated on a latent level and were hence free from measurement error. Nevertheless, certain limitations should be considered. First, it was possible to quantify intrinsic and extrinsic motivation and reading amount only on the basis of aggregated questionnaire data. Future research should implement more differentiated measurements of each construct, potentially including other measurement instruments, such as diaries or checklists. Second, we examined a sample of elementary school children from Grades 3 to 6. Future studies should determine whether our findings can be generalized to other age groups. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility that variance in Grade 3 reading achievement is confounded with motivation. Further questions remain unresolved and warrant attention in future studies. For example, how exactly is the relationship between extrinsic motivation and reading literacy mediated? What are the processes underlying this relationship? At this stage of research, the mechanisms remain unclear, and further investigation is necessary: whether the importance of extrinsic motivation is due to the corruption of intrinsic by extrinsic motivation, whether the negative valence of the activity itself is caused by extrinsic motivation associated with some form of pressure, or how else this aspect of motivation might be relevant for performance development. Future research needs to investigate how parents and educators can mitigate the negative effects of extrinsic motivation on students’ reading development. In conclusion, this study advances research knowledge by disentangling the roles of extrinsic and intrinsic motivation for reading literacy and reading amount and highlighting the substantial effect of prior achievement on later motivation. This effect has important implications for practice. Many teachers and parents go to great lengths to increase or maintain students’ intrinsic reading motivation. However, our longitudinal findings underline the importance of enabling early experiences of reading competence: Reading literacy is highly stable over time, and earlier intrinsic motivation does not explain future achievement above the level attained in Grade 3. From a theoretical point of view, the problem is thus not always that students fail to learn because they lack motivation; rather, students lack motivation because they do not experience progress and competence. The present findings indicate that this holds even for the very young students analyzed here. In order to motivate students, teachers must therefore offer them the experience of progress and competence. Additionally, the negative effects of extrinsic motivation on later reading literacy have clear implications for teachers and parents. Student reading motivated by the wish to please parents or teachers does not promote achievement gains over time. In sum, these findings are of high relevance for practice and research, especially in calling attention to how educators and parents articulate reading-related expectations and to the detrimental impact of extrinsic motivation on the development of reading literacy. References Aarnoutse, C., & van Leeuwe, J. (1998). Relation between reading comprehension, vocabulary, reading pleasure, and reading frequency. Educational Research and Evaluation, 4, 143–166. doi:10.1076/ edre.4.2.143.6960 Aarnoutse, C., van Leeuwe, J., Voeten, M., & Oud, H. (2001). Development of decoding, reading comprehension, vocabulary and spelling during the elementary school years. Reading and Writing, 14, 61– 89. doi:10.1023/A:1008128417862 Anderson, R. C., Wilson, P. T., & Fielding, L. G. (1988). Growth in reading and how children spend their time outside of school. Reading Research Quarterly, 23, 285–303. doi:10.1598/RRQ.23.3.2 Baker, L., Dreher, M. J., & Guthrie, J. T. (Eds.). (2000). Engaging young readers: Promoting achievement and motivation. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Baker, L., & Wigfield, A. (1999). Dimensions of children’s motivation for reading and their relations to reading activity and reading achievement. Reading Research Quarterly, 34, 452– 477. doi:10.1598/RRQ.34.4.4 Baker, S., Simmons, D., & Kameenui, E. J. (1995). Vocabulary acquisition: Curricular and instructional implications for diverse learners (Technical Report No. 14). Eugene, OR: National Center to Improve the Tools of Educators. Cipielewski, J., & Stanovich, K. E. (1992). Predicting growth in reading ability from children’s exposure to print. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 54, 74 – 89. doi:10.1016/0022-0965(92)90018-2 Cunningham, A. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (1997). Early reading acquisition and its relation to reading experience and ability 10 years later. Developmental Psychology, 33, 934 –945. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.33.6.934 Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (1999). A meta-analytic review examining the effects of extrinsic rewards on intrinsic motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 627– 668. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.627 Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and selfdetermination in human behavior. New York, NY: Plenum. Donahue, P. L., Daane, M. C., & Yin, Y. (2005). The nation’s report card: Reading 2003 (Publication No. NCES 2004 – 453). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Duke, N. K., & Pearson, P. D. (2002). Effective practices for developing reading comprehension. In A. E. Farstrup & S. J. Samuels (Eds.), What research has to say about reading instruction (3rd ed., pp. 205–242). Newark, DE: International Reading Association. Durkin, D. (1993). Teaching them to read (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. Elliott, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 5–12. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5 INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION Fuchs, L. S., Fuchs, D., Hosp, M. K., & Jenkins, J. R. (2001). Oral reading fluency as an indicator of reading competence: A theoretical, empirical, and historical analysis. Scientific Studies of Reading, 5, 239 –256. doi: 10.1207/S1532799XSSR0503_3 Gear, A., Wizniak, R., & Cameron, J. (2004). Rewards for reading: A review of seven programs. Alberta Journal of Educational Research, 50, 200 –203. Gee, J. (2001). Reading as situated language: A sociocognitive perspective. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 44, 714 –725. doi:10.1598/ JAAL.44.8.3 Gottfried, A. E., Fleming, J. S., & Gottfried, A. W. (2001). Continuity of academic intrinsic motivation from childhood through late adolescence: A longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93, 3–13. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.93.1.3 Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.). Reading research handbook (Vol. 3, pp. 403– 422). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Barbosa, P., Perencevich, K. C., Taboada, A., Davis, M. H., . . . Tons, S. (2004). Increasing reading comprehension and engagement through concept-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96, 403– 423. doi:10.1037/00220663.96.3.403 Guthrie, J. T., Wigfield, A., Metsala, J. L., & Cox, K. E. (1999). Motivational and cognitive predictors of text comprehension and reading amount. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 231–256. doi:10.1207/ s1532799xssr0303_3 Heller, K. A., & Perleth, C. (2000). KFT 4–12⫹R. Kognitiver Fähigkeitstest für 4 bis 12 Klassen, Revision [Cognitive Abilities Test for Grades 4 to 12, revision]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. Hidi, S. (2000). An interest researcher’s perspective: The effects of extrinsic and intrinsic factors on motivation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 309 –339). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-012619070-0/50033-7 Higgins, E. T., Lee, J., Kwon, J., & Trope, Y. (1995). When combining intrinsic motivation undermines interest: A test of activity engagement theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 749 –767. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.68.5.749 Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi:10.1080/ 10705519909540118 International Reading Association. (2000). Excellent reading teachers: A position statement of the International Reading Association. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 44, 193–200. Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Klicpera, C., & Gasteiger-Klicpera, B. (1993). Lesen und Schreiben: Entwicklung und Schwierigkeiten [Reading and writing: Development and difficulties]. Bern, Switzerland: Huber. Kolen, M. J., & Brennan, R. L. (2004). Test equating, scaling, and linking: Methods and practices (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer. Kortenbruck, M. (2007). Entwicklung der Lesekompetenz: Einfluss von Motivation und Geschlecht [Development of reading literacy: The influence of motivation and gender]. (Unpublished Diplom thesis). Free University of Berlin, Berlin, Germany. Küspert, P., & Schneider, W. (1998). Würzburger Leise Leseprobe (WLLP) [Würzburg Silent Reading Test]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. Lehmann, R. H., Peek, R., & Poerschke, J. (1997). HAMLET 3– 4: Hamburger Lesetest für 3 bis 4 Klassen [HAMLET 3– 4: Hamburg Reading Test for Grades 3 to 4]. Weinheim, Germany: Beltz. McElvany, N. (2008). Förderung von Lesekompetenz im Kontext der 783 Familie [Promotion of reading competence in the family context]. Münster, Germany: Waxmann. McElvany, N., & Artelt, C. (2009). Systematic reading training in the family: Development, implementation, and evaluation of the Berlin Parent–Child Reading Program. Learning and Instruction, 19, 79 –95. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.02.002 McElvany, N., Becker, M., & Lüdtke, O. (2009). Die Bedeutung familiärer Merkmale für Lesekompetenz, Wortschatz, Lesemotivation und Leseverhalten [The role of family variables in reading literacy, vocabulary, reading motivation, and reading behavior]. Zeitschrift für Entwicklungspsychologie und Pädagogische Psychologie, 41, 121–131. doi: 10.1026/0049-8637.41.3.121 McElvany, N., Kortenbruck, M., & Becker, M. (2008). Lesekompetenz und Lesemotivation: Entwicklung und Mediation des Zusammenhangs durch Leseverhalten [Reading literacy and reading motivation: Their development and the mediation of the relationship by reading behavior]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 3/4, 207–219. doi:10.1024/ 1010-0652.22.34.207 Morgan, P. L., Farkas, G., & Hibel, J. (2008). Matthew effects for whom? Learning Disabilities Quarterly, 31, 187–198. Morgan, P. L., & Fuchs, D. (2007). Is there a bidirectional relationship between children’s reading skills and reading motivation? Exceptional Children, 73, 165–183. Mullis, I. V. S., Martin, M. O., Kennedy, A. M., & Foy, P. (2007). IEA’s Progress in International Reading Literacy Study in Primary School in 40 countries. Chestnut Hill, MA: TIMSS & PIRLS International Study Center, Boston College. Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998 –2008). Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Author. Naceur, A., & Schiefele, U. (2005). Motivation and learning: The role of interest in construction of representation of text and long-term retention: Inter-and intra-individual analyses. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 20, 155–170. doi:10.1007/BF03173505 Nagy, W. (1988). Teaching vocabulary to improve reading comprehension. Newark, DE: International Reading Association. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction: Reports of the subgroups (Report of the National Reading Panel, NIH Publication No. 00 – 4754). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. Nauck, J., & Otte, R. (1980). Diagnostischer Test Deutsch [Diagnostic test German]. Braunschweig, Germany: Westermann. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2001). Knowledge and skills for life: First results from PISA 2000. Paris, France: Author. Pintrich, P. R., & Schrauben, B. (1992). Students’ motivational beliefs and their cognitive engagement in classroom academic tasks. In D. H. Schunk & J. L. Meece (Eds.), Student perceptions in the classroom (pp. 149 –183). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Pintrich, P. R., & Schunk, D. H. (2002). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and application (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall. Pressley, M., Borkowski, J. G., & Schneider, W. (1989). Good information processing: What it is and how education can promote it. International Journal of Educational Research, 13, 857– 867. doi:10.1016/08830355(89)90069-4 Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54 – 67. doi:10.1006/ceps.1999.1020 Schaffner, E., & Schiefele, U. (2007). Auswirkungen habitueller Lesemotivation auf die situative Textrepräsentation [Effects of habitual reading motivation on the situative representation of text]. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht, 54, 268 –286. 784 BECKER, MCELVANY, AND KORTENBRUCK Schiefele, U. (1999). Interest and learning from text. Scientific Studies of Reading, 3, 257–279. doi:10.1207/s1532799xssr0303_4 Seymour, P. H., Aro, M., & Erskine, J. M. (2003). Foundation literacy acquisition in European orthographies. British Journal of Psychology, 94, 143–174. doi:10.1348/000712603321661859 Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422– 445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 Snow, C. E. (2002). Reading for understanding: Toward a research and development program in reading comprehension. Santa Monica, CA: RAND. Snow, C. E., Scarborough, H. S., & Burns, M. S. (1999). What speechlanguage pathologists need to know about early reading. Topics in Language Disorders, 20, 48 –58. Taboada, A., Tonks, S., Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. (2009). Effects of motivational and cognitive variables on reading comprehension. Reading and Writing, 22, 85–106. doi:10.1007/s11145-008-9133-y Taylor, B. M., Frye, B., & Maruyama, J. (1990). Time spent reading and reading growth. American Educational Research Journal, 27, 351–362. Unrau, N., & Schlackman, J. (2006). Motivation and its relation to reading achievement in an urban middle school. Journal of Educational Research, 100, 81–101. doi:10.3200/JOER.100.2.81-101 Verhoeven, L., & Van Leeuwe, J. (2008). Prediction of the development of reading comprehension: A longitudinal study. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 22, 407– 423. doi:10.1002/acp.1414 Wang, J. H., & Guthrie, J. T. (2004). Modeling the effects of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, amount of reading, and past reading achievement on text comprehension between U.S. and Chinese students. Reading Research Quarterly, 39, 162–186. doi:10.1598/RRQ.39.2.2 Weiss, R. (1987). Wortschatz (WS) und Zahlenfolgen (ZF): Ergänzungstests zum Grundintelligenztest CFT-20 [Basic Intelligence Test, Scale 2, CFT 20]. Göttingen, Germany: Hogrefe. Wigfield, A., Eccles, J. S., Schiefele, U., Roeser, R. W., & Davis-Kean, P. (2006). Development of achievement motivation. In W. Damon & N. Eisenberg (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology (6th ed., pp. 933–1002). New York, NY: Wiley. Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Motivation for reading: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 32, 57–58. (Appendix follows) INTRINSIC AND EXTRINSIC READING MOTIVATION 785 Appendix Full Model of Figure 3 ε ε dt78 dt79 .91*** ε ε ε ε dt76 dt73 dt29 dt81 .92*** -.82*** .66*** im4val1 dt80 1 .55*** .84*** im4imp im4val2 .74*** .83*** .91*** -.55*** Intrinsic Motivation 4 ε ε Comp. 3 .75*** .63*** Decod 3 .01 .37*** .11+ Literacy 3 .79*** ε .09 Amount 4 .67*** .61*** .93*** .14* Vocab 3 -.01 -.52*** .65*** deo1 .82*** lv4dust .85*** em4p .71*** .69*** .80*** dt65 dt67 dt70 ε ε ε .64*** em4sc 1 dt75 dt42 dt43 ε ε deo2 1 .82*** .90*** Literacy 6 lv4dup lv4freq Extrinsic Motivation 4 Comp 6 ε .62*** Decod 6 ε Vocab 6 ε .74*** .81*** ε .78*** ε -.24*** dt95 .59*** em4ins .79*** .69*** .71*** dt72 dt74 dt63 ε ε ε Note. Residual variances of the indicators of literacy in Grades 3 and 6 were constrained to be equal over time; indicators of literacy in Grades 3 and 6 were allowed to correlate specifically for each domain (e.g., decoding 3 with decoding 6). For decoding (r ⫽ .51, SE ⫽ .05) as well as for vocabulary (r ⫽ .17, SE ⫽ .08), the correlation was statistically significant (not depicted here). im ⫽ intrinsic motivation; em ⫽ extrinsic motivation; dt ⫽ items from student questionnaire; deo ⫽ items from parents’ questionnaire; lv ⫽ reading behavior; comp ⫽ comprehension; decod ⫽ decoding; vocab ⫽ vocabulary. ⴱ p ⱕ .05. ⴱⴱⴱ p ⱕ .001. Received June 15, 2009 Revision received April 12, 2010 Accepted May 6, 2010 䡲