- Ninguna Categoria

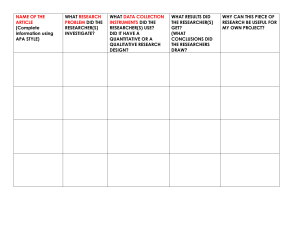

Educational Research: Quantitative & Qualitative Methods

Anuncio