- Ninguna Categoria

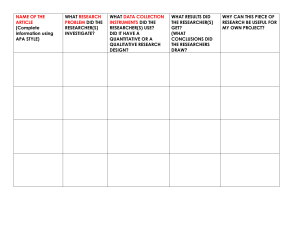

Mobile Market Research Handbook: Tools & Techniques

Anuncio