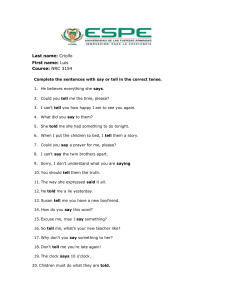

© 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. The National Watch and Clock Museum by Guest Curator Doug Cowan Incense Timepieces of East Asia Introduction ost of the devices currently displayed in the Sense of Time exhibit at the National Watch and Clock Museum are commonly called incense clocks, or fire clocks. They do tell time by burning various forms of incense, but they are not properly called clocks, because they do not strike the hours, nor do they tell the time as we expect—as the immediate delivery, night or day, of the hour, minute, and even second. Instead, they measure the passage of time, as a sandglass, egg timer, or chronograph does. For this article we will call them simply “timepieces.” M HUGH DOUGHERTY www.nawcc.org www nawcc org NWCM East Asian timekeeping was historically concerned with the passage of time, and the epoch, for example, of the ruling dynasties. The vast majority of Chinese people did not own Western-style clocks and relied on the sun and the motions of the stars. Actionable time, such as the start of meetings or ceremonies, was used in temples and palaces, and by city officials. Even these were not pursued by time to the level required in the West since the nineteenth century. Figure 1 shows an ancient Chinese city clepsydra, or water clock. These public clocks displayed the time by means mean of a floating gauge. These dev devices and sundials w were the main official timekeepers until u approximately approximat A.D. 1000. C Can- Figure 1. Traditional Chinese water clock. dles and a sort of fuse cord, ord, knot knotted along its length to indicate time intervals, were also used. To further complicate matters, ers, there was more than one timee telling standard in the vast Chinese hinese territories, and throughout East Asia the actual length of the time intervals was adjustable and varied aried with the seasons. Why incense? Because it was there in everyday life! I ncense burning in the West is connected to various religions, and usage has spread somewhat into the mainstream via youth and “counter” cultures. But in the Middle and Far East its use is much more ancient and inclusive. Buddhist ceremonies undoubtedly had most to do with its spread from India to the Orient in the sixth century A.D., as that religion rapidly converted China, Korea, Japan, and other East Asian cultures. In worship, the smoke from incense was thought to carry prayers to heaven as well as to enable communication with souls of the dead. Nonreligious uses were also prevalent: to ward off demons; to perfume clothing; to aid concentration; mood enhancement; to cover unpleasant smells; and simply as a “must-have” ambience in everyday life at all levels of society. Figure 2 shows four incense burners, called censers. These burners are not timepieces; you can readily tell this by looking inside. They tend to be round bottomed, whereas the timekeepers must have flat fire pans to ensure even burning rates. Vastly more censers exist than timepieces, and they tend to be somewhat more decorative and were often made Figure 2. Chinese censers dating from the eighteenth century to the present. NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin • February 2010 • 3 © 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. The National Watch and Clock Museum Figure 3. Wooden dragon boat. Incense Coils I from more exotic materials, such as porcelain or stone. Most timepieces are made from metal, specifically, bronze paktong or pewter. For a more complete history of incense, see S. A. Bedini. The Scent of Time, volume 53, part 5 (Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, 1963). Incense Timekeeping Incense Sticks A ncient history is circumstantial, but it is likely that common incense sticks were adapted for telling time quite informally. A literature reference alludes to a meeting to take place “in the time of two incense sticks.” The approximate amount of time that was meant must have been well known, but for us it could vary widely, depending on the size and composition of the sticks. It became the custom to mark the desired time intervals on the incense sticks, which were then burned standing vertically in a bowl or censer. An example is shown in Figure 2. An unmarked stick is a censer; marked for time intervals, it becomes a timepiece. Modern incense sticks are usually wooden strips dipped into an incense paste and dried. This does not work well enough for timekeeping because the burn rate is hard to control. Instead, time telling sticks were made by extruding a paste of ground ingredients through a “draw plate,” just like making wire, and cutting and drying the extruded line. Duration of burn would be determined by the incense paste formula and the diameter and length of the stick. It seems likely that one of each batch would be calibrated for burn rate before the other ncense coils were made much like incense sticks but were much longer and bent into a coil shape. When suspended from one end, they formed a cone-shaped coil (picture an oversized mosquito repellent sticks were marked for time intervals. coil). The main advantage was that Time-calibrated beeswax candles the length of burn easily surpassed were in use at the same time, but the a day if desired. The time intervals incense sticks would have been pre- could be painted onto the coil to ferred because they burned without more accurately measure time passopen flame and were probably also ing. They had one other advantage: less expensive and more available. the coils would support the equivaIncense formulas for all forms of lent of a clock’s passing strike or an timekeeping were based upon finely alarm. To achieve this a ground sandalwood or heartwood small bell was susfrom very dense woods such as aloe. To this, ingredients were added to adjust the burning rate. Clay was used to retard burning and various resins accelerated it. Of course, key additions were fragrance components, such as frankincense, patchouli, or clove; some of those compounds could affect burn rate as well. The paste was made in a portion of wine or water, and if the sticks proved brittle when dried, a binding agent was included as well. Powdered incense did not require the preparation of a stick and so it was much easier to prepare. (See more under Incense Powder Seals on page 5.) Documented examples of nonreligious timekeeping uses of incense sticks include the following: timing miners’ underground shifts; medicine use intervals at home; ship’s watch timing; court ceremonies; timing official executions; civil service lunch breaks; and early morning messenger departures. And the form lasted! Stick timepieces that were two feet long and lasted half a day were still being sold in China in 1899. 4 • February 2010 • NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin www.nawcc.org © 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. The National Watch and Clock Museum pended at the desired spot by means of a thread. When the fire reached the thread and burned it, the bell fell onto a metal plate that served as a one-note strike or alarm. Most of these coils were used in temples to time prayers or to alert the monks to announce the time by drums to the townspeople. In remote areas of East Asia, they were seen still in use in the mid-twentieth century. There are two types. The most common is of heavily lacquered and painted wood, lined with a pewter firebox and using nine wires to suspend the horizontal incense stick laid along the axis of the dragon. These timepieces were approximately 16-24 inches long. While most represent dragons, there are also examples that depict human figures, or snaillike scrolls at each end of the timepiece. They may have been intended to burn for half a day. The second Dragon Boats type, made of cast bronze, is very ragons hold a special place in ornate and somewhat smaller. Both East Asian mythology. The types could announce a preset time dragon boat incense timepiece (Fig- by the thread and bell system menure 3) was in use by about A.D. tioned above. It is interesting to note 1100, and was designed to that most pictures erroneously show simulate real dragon the thread to be above the incense boats raced as stick. It should be below the stick to part of spring ensure burn through. These imagifestivals. native timepieces were used well into the nineteenth century, but toward the end their timekeeping job was unknown or ignored and they became novelty censers instead. D Incense Powder Seals (hsiang yin) I Figure 4. Example of a powder seal. www.nawcc.org ncense seals are so named because the trail for the incense burn and the timepiece decoration often resemble “picture words” from the ancient Chinese pictographic language. This version of the Chinese written language has not been formally used for many centuries, but it is still admired and was used for artists’ signatures and sometimes for marks on porcelain well into the twentieth century. Early examples circa the eleventh century looked very much like Figure 4 and worked in the same way. Powdered incense is very much easier to prepare and these timepieces were designed specifically for powder use. Figure 4 is actually a modern three-hour burner, sold as a censer. It is 5.5 inches in diameter. Slightly larger six-hour burners are also avail- able. Both would function well as timepieces with longer burning incense and time interval markings. The ancient ones would have been made from wood or stone and been about 12 inches in diameter. These served many civic uses, but two of the most important were the calibration of the town clepsydra and the timing of the important night watch terminating with the morning opening of the town gates. Water clepsydras, despite frequent upgrades by Chinese engineers, were unreliable in times of water shortage or freezing weather. Their replacement was at first sand clepsydras, which were hampered by the inability to control humidity. Sundials were normally used to check clepsydras timekeeping, but this was of no use when the sun was not shining. Circa 1073 the invention of the 24-hour seal timepiece became the standard for timekeeping. These were marked with “notches” to mark the desired intervals and were lit at noon each day. Examples of these early seal timepieces could be made to run for more than a lunar month. The night watch incense seals came in five different lengths of incense trail. East Asian countries used the ancient timekeeping standard as affected by the seasons. That is, night and day intervals (about two of our current hours) were counted separately. As the seasons changed, the length of the night (darkness) changed and the night watch timepieces had to reflect this. Few records have been found describing timekeeping with incense seals during the Middle Ages. But in the 1870s a Chinese scholar named Ting Yün (courtesy name Moon Lake) revived interest in the seals, which were then made in metal. These objects comprise the main part of the Museum exhibit. I have not found when metal incense timepieces gained common use, but they had several advantages over stone and wood incense timepieces. They were NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin • February 2010 • 5 © 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. Figures 5 and 6. Paktong and copper leafshaped seal. more robust, would not wear out, were draft/windproof, easily portable, and certainly more artistically attractive. The metal incense timepieces kept better time, in particular because of the innovation of an ash fire bed for the incense trail to burn within. Wood ash allows the penetration of air, thus making the top and bottom of the burning incense trail to be close in temperature and oxygen availability—two important variables unavailable with stone or wood substrates. Their enclosing covers and built-in trays, which contained incense tools and the firebox, allowed for portability. The incense burning trail, instead of being engraved into the base, was provided by a cut metal template also carried in one of the trays. Figure 5 shows an incense seal in the shape of a leaf, dated 1878. It is made of paktong metal with invisibly soldered copper beading. The object is about five inches long. The cover is translated as “know the way of the picture,” the date made, and the sign of Moon Lake (Ting Yün). This is one of the few dated examples that the writer has seen, out of approximately 100 seals examined. In Figure 5 we see the cover, template for the burning trail, an ash-flattening tool, and the spoon for the incense. The seal would have been used as follows: The middle tier of the seal shown in Figure 6 contains the firebox. This is a flat pan containing about one quarter of an inch of wood ash. This is dampened, and the flattened with the handled flattening tool. The fire trail template is laid on the ash and with the handle tip of the little shovel, a groove is made in the ash following the pattern of the template. In this case the template pattern is meant to signify the thought “green sky.” The incense is poured into the groove with the template in place, deepening the incense level. The template is carefully removed, the incense trail lighted at one end, and the cover placed over the fuel pan to shield draughts and prevent fires. Ting Yün’s incense seals typically burned for one quarter or half a full day. This one is probably a six-hour (Western) example. The first incense seals were made of bronze though few of those survive. Most seals are made of paktong or pewter. Paktong is considered as the second and most popular metal used throughout the Middle Ages and until the eighteenth century. It is an alloy of approximately 60 percent copper, 25 percent zinc, and 15 percent nickel. Refining paktong was a 6 • February 2010 • NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin Figure 7, above. Seals in various shapes. Chinese state secret during the third century when it was used for coinage. Called “white silver” the metal is moderately hard but can be cast or rolled, folded, and polished. Paktong is corrosion resistant and long lasting. The color of the metal varies from a silvery sheen to a mellow brass yellow, or even coppery red, depending on the specific content of the individual metals. Pewter is well known to us and was in use by the late seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. It is soft and easily worked, but not very heat resiswww.nawcc.org © 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. The National Watch and Clock Museum Figure 8. Scepter-shaped seal. tant. Therefore, pewter seals usually have a brass vent in the cover and sometimes brass firepans to resist melting. Pewter seals are also more likely to bear trademarks of the makers or sellers, perhaps indicating relatively less age. Brass was well known to the Chinese from early times but for reasons unknown was seldom used to make entire seal timepieces. late nineteenth century, more than enough of them around to make incense seals unneeded. It seems likely that the love of incense that continues today was the driving force for this revival of incense seals. The seal shapes (scepter, melon, lute, leaf) as well as the patterns of the templates (long life, auspicious, marital fertility, peace of mind, etc.) and the decoration of the covers (prunus blossoms, butterflies, fruit Incense Seal Shapes bats, marital happiness, etc.) were t is probable that simple-shaped all happy feelings symbols. Figure 9 seals were most affordable and shows a seal timepiece in its wooden common. Figure 7 shows examples of presentation box, and it is believed round, rectangular, and urn-shaped that many incense seals were gifted seals in paktong or pewter. As time in this way. Also in the more detailed went on, more elaborate shapes and objects, the sides were engraved with, sizes were produced. Figure 8 shows a for example, the many ancient pictovery large j’ui (scepter)-shaped time- graphic drawings for long life, script piece with a carved wooden stand. It expressing thoughtful ideas, or with is 20 inches long and is made of cast peaceful landscapes. and rolled paktong with elaborate dragon and fruit bat decorations in Ting Yün (1800-1879) the cover. The j’ui scepter was particularly popular in the late 1880s, his Chinese scholar was the and this shape had many subjective stimulant for the great popularmeanings, including “wishes ful- ity revival of incense timepieces in filled” or “the arm of Buddha.” It is the late nineteenth century. Living said to have been copied from the on a remote island shape of a sacred mushroom and is a in the mouth of the truly graceful design, found through- Yangtze river, late in out Chinese art. his life he completed Late nineteenth-century seal Chi- a study of the annese incense timepieces were likely cient designs of seal symbolic gifts to newlyweds, friends, incense timepieces and business associates. China had and composed a converted to Western timekeeping book of 100 such in the late seventeenth century, and designs “in honor of though most Chinese found maintenance of the Western mechanical Figure 9. Seal timepiece and wooden clock baffling, there were, by the I T the ancients.” This book published in Shanghai in 1878, shortly after his death, is titled Yinxiang tupu. Only two copies are now known to exist, one is in the U.S. Library of Congress, OCLC #12335689. It is, of course, in obsolete Chinese, but the drawings should be interesting, indeed. Ting Lun also made or commissioned several incense seal products that bore his name and attribution to “the ancients.” A large number of contemporary obituaries from other Chinese scholars and artists clearly show that he really did do these things. What we do not know is how many of the designs are really copied from much earlier incense seals, and how many were original designs based on ancient symbols not relating to incense seals. Researchers believe that the incense seal was made in various forms from circa 700 until the end of the Ch’ing dynasty in 1912. The sources of production are not understood, though a small amount of data suggests that the later pewter examples tended to be made near Canton and the paktong ones near Shanghai. The following 70-plus years of war and revolution caused this historical record to be lost. Most modern Chinese are not aware of the timekeeping aspects of the seals, and most owners obtained their examples as unidentified artwork or incense burners (censers) from the Hong Kong antique shops in the 1970s, due to the emptying of warehouses filled with Maoistera confiscated personal property. Silvio A. Bedini, who passed away presentation box. www.nawcc.org NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin • February 2010 • 7 © 2010 National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, Inc. Reproduction prohibited without written permission. in late 2007, was the source of virtually all of the organized information regarding timekeeping with incense. He worked at the Smithsonian Institution as curator of the Department of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, but his life’s passion was historical research including horological topics (he authored at least 14 books). His first important publication on the incense timekeepers, The Scent of Time (American Philosophical Society, 1963), was guided by at least 40 other translators, historians, collectors, and professors from many countries. Bedini was quite involved with the collector who assembled the collection now on display at the Museum. Bedini’s last publication on this subject was the 1994 book from Cambridge University Press, The Trail of Time, a 341-page tour de conclusions in the book are uncertain and speculative. I am sure that he learned much more between 1994 and 2007, since I know that he was still interested in the subject. I came along too late in my own interest to talk with him, and unless his heirs discover and contribute more of his research we will have to await another like him to take on the problems of researching in Chinese, a language that has changed dramatically over many centuries on a topic of little interest to Chinese historians. Japanese Incense Timepieces J apan adopted Buddhism and incense burning about 100 years later than China. The main difference is that the country was intentionally isolated from the 1600s until 1873 when, by dictate, Japan adopted Western timekeeping. All of their previous timekeepers became obsolete, and the purpose of their incense timekeepers is mostly forgotten. Japan knew and used incense sticks and incense seals for keeping time but their contribution was the wooden kobandokei (incense clock). These articles as shown in Figure 10 were almost entirely made of fire-resistant wood such as cryptomeria, including even the tools (Figure 11) and the firebox. The principles of operation were just like the Chinese metal incense seals—an incense trail laid into a bed of wood ash, with a cover to protect the burn from drafts and wind. They came in various sizes, from about 8 inches tall with no storage drawers, probably for home use, to 20-inch tall models with two drawers below to store tools, template, and incense powder, likely for temple use. In general, the Japanese incense timepieces were used in the temples, to time temple prayers, decide when to strike the drums for community prayer, and to make sure that there was a “holy fire” that never was extinguished. Japanese tools included a wooden rake, to smooth lumps out of the ash before starting another burn cycle. Unlike Chinese seals, the templates of Japanese timepieces were smaller than the area of the firebox. This allowed the incense burn pattern to be varied slightly, according to purpose. In addition, the template often had ridges on its underside. These would leave lines in the ash that could be used to count the progression of the burn—in effect telling the time. Small time or event markers could be stood upright in the ash alongside the incense trail, with little horizontal plates indicating the time or event to be started or stopped. Finally, these little markers could be made of small incense tabs of different scents so that you could “read” the time without even looking at the timepiece. 8 • February 2010 • NAWCC Watch & Clock Bulletin Another novel incense Japanese timepiece, in use well into the twentieth century, was the geisha “clock.” Visits to the geisha of your choice were charged according to the number of 30-minute incense sticks burned while you were with her. A long box contained vertical slots holding the sticks for the ladies working in the house. For a good general summary of East Asian timekeeping see Bernard Stoltie’s December 2006 Bulletin article, “Asian Timekeeping.” D Figure 10. Japanese Jokoban. Figure 11. Toolkit for a Japanese Jokoban. www.nawcc.org