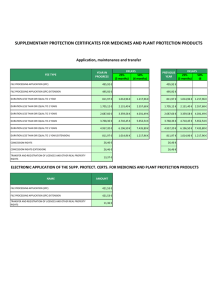

Clinical Toxicology ISSN: 1556-3650 (Print) 1556-9519 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ictx20 Accidental pharmacological poisonings in young children: population-based study in three settings Jane C. Bell, Jason P. Bentley, Catriona Downie, Rose Cairns, Nicholas A. Buckley, Annette Katelaris, Sallie-Anne Pearson & Natasha Nassar To cite this article: Jane C. Bell, Jason P. Bentley, Catriona Downie, Rose Cairns, Nicholas A. Buckley, Annette Katelaris, Sallie-Anne Pearson & Natasha Nassar (2018): Accidental pharmacological poisonings in young children: population-based study in three settings, Clinical Toxicology, DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2017.1422509 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1422509 View supplementary material Published online: 15 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 102 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ictx20 CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY, 2018 https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2017.1422509 POISON CENTRE RESEARCH Accidental pharmacological poisonings in young children: population-based study in three settings Jane C. Bella , Jason P. Bentleya , Catriona Downieb, Rose Cairnsc,d Annette Katelarisd , Sallie-Anne Pearsona,d,e and Natasha Nassara , Nicholas A. Buckleyd , a Menzies Centre for Health Policy, School of Public Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; bSydney Hospital and Sydney Eye Hospital, Sydney, Australia; cNew South Wales Poisons Information Centre, The Children's Hospital at Westmead, Sydney, Australia; d Sydney Medical School, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; eMedicines Policy Research Unit, Centre for Big Data Research in Health, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: Pharmacological poisonings in young children are avoidable. Previous studies report calls to poisons centres, presentations to emergency departments (ED) or hospital admissions. There are limited data assessing concurrent management of poisonings across all three settings. We aimed to describe accidental pharmacological poisonings in young children across our Poisons Information Centre (PIC), EDs and hospitals. Methods: A population-based study in New South Wales, Australia, of PIC calls, ED presentations and hospital admissions for accidental pharmacological poisoning in children aged <5 years, 2007–2013. We examined trends, medicines responsible and subsequent management. Medicines were coded using ICD10-AM diagnosis codes (T36-50). Results: Over 2007–2013, pharmacological poisonings accounted for 67,816 PIC calls, 7739 ED presentations and 2082 admissions. Rates (per 10,000 children) of PIC calls declined from 220 to 178; ED presentations were stable (22–24), with a decrease in emergency cases offset by an increase in semi- or non-urgent presentations; hospital admissions declined (8–5). Most PIC calls related to “non-opioid analgesics” (25%), and “topical agents” (18%). Nearly every day, one child aged <5 years was admitted to hospital for poisoning. “Benzodiazepines”, “other and unspecified antidepressants”, “uncategorised antihypertensives”, and “4-aminophenol derivatives” accounted for over one-third of all admissions. Most PIC calls (90%) were advised to stay home, 6% referred to hospital. One-quarter of ED presentations resulted in admission. Conclusions: Poisonings reported to PIC and hospitals declined, however, non-urgent ED presentations increased. Strategies to reduce therapeutic errors and access to medicines, and education campaigns to improve Poisons Centre call rates to prevent unnecessary ED presentations are needed. Received 29 August 2017 Revised 18 December 2017 Accepted 22 December 2017 Published online 13 January 2018 Introduction Pharmacological poisoning in young children remains a common [1–3], sometimes fatal [4,5], yet preventable injury. Reports of poisoning prevalence and trends, and medicines responsible are usually based on single data sources, such as poisons centres [6–10] or emergency department (ED) presentations [2,11–17], or both [1,18,19]. Findings from these two settings are dependent on population access and utilization and therefore subject to under-reporting, and differential reporting by medicine type, making changes over time difficult to interpret. In contrast, population-based hospitalization data [20–23] comprise all severe poisonings requiring inpatient treatment. Therefore, while less subject to reporting bias, these data do not reflect all community poisoning exposures. We aimed to describe the burden of accidental pharmacological poisonings in young children, and the most common medicines implicated, using population-based data from KEYWORDS Poisons centers; children; pharmacological poisonings three state-based health services in Australia managing poisonings. Methods We conducted a population-based study to evaluate accidental pharmacological poisonings occurring in children aged <5 years, in New South Wales (NSW) Australia over the period 2007–2013. NSW is the most populous state in Australia, comprising around 8 million people, one-third of the national population [24]. We ascertained pharmacological poisonings from three independent data sources: the NSW Poisons Information Centre (PIC), presentations to NSW hospital EDs and admissions to NSW hospitals. If children accessed more than one of these health settings, they were included in analyses for each health setting as individuals could not be linked across the three data sources. CONTACT Jane C. Bell [email protected] Menzies Centre for Health Policy, Level 2, Charles Perkins Centre D17, University of Sydney, Sydney, NSW 2006, Australia Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here. ß 2018 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group 2 J. C. BELL ET AL. Data sources The NSW PIC provides advice to health professionals and the public on the management of poisoned and envenomed patients [25]. The PIC is staffed by pharmacists and medical scientists with additional training in toxicology; and consultant medical toxicologists manage complex cases. The PIC handles all calls within NSW from 6 am-midnight, and all calls in Australia for seven nights each fortnight. For each call, demographic information of the exposed person (age, sex), characteristics of the caller (source: family, community, hospital; Australian state), and exposure details (substance/s involved, route, dose, timing, exposure intent [for example, accidental, therapeutic error]) are collected. Only calls from within NSW were included in analyses. The NSW Emergency Department Data Collection includes information on patient demographics; timing, urgency and referral source of presentation; mode of arrival and separation. Data are collected by staff in EDs of public hospitals. In 2010 (approximate midpoint of our study period), around 90/ 150 EDs participated in the ED data collection. As the larger EDs all participated, a substantial proportion of the NSW population is covered (estimated to be 82–87% of all ED presentations). During the study period, there were only three private EDs in NSW, and all EDs at designated paediatric hospitals were included [26]. The NSW Admitted Patient Data Collection is a census of all admissions to all NSW public and private hospitals and collects individual demographic and clinical information with diagnoses and external causes (circumstances in which the poisoning occurred) coded according to the 10th revision of the International Classification of Disease, Australian Modified version (ICD10-AM). Procedures are coded using the Australian Classification of Health Interventions. Data are abstracted from hospital records by trained and certified medical coders. Pharmacological poisoning diagnosis, management and outcomes To compare pharmacological poisonings across the three data collections, we coded the medicine responsible to the ICD10AM, as this system was common to hospital admissions and ED presentations. We defined pharmacological poisonings as those with diagnostic codes T36-T50. For each PIC call, we coded the substance responsible to the ICD10-AM diagnosis code. However, calls for children exposed to more than one pharmacological substance were classified as ‘multiple exposures’ and not assigned a specific diagnostic code, as the primary exposure could not be determined. Each ED uses one of three classification systems for coding the clinical diagnosis: ICD9-CM (Clinical Modification), ICD10-AM or Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (SNOMED-CT) [27]. Given the lack of sensitivity of SNOMED-CT coding, where over half of diagnoses are defined by symptom (e.g. nausea or vomiting) [28], we identified presentations for pharmacological poisoning using only ED presentations coded using ICD9-CM (and mapped to ICD10-AM) or ICD10-AM. We used this subset of ED poisonings coded with ICD10-AM to describe the characteristics of children affected by poisonings, and the medicines involved. To calculate ED presentation rates for accidental poisoning in NSW as a whole, we extrapolated annual numbers and rates from presentations coded using ICD10-AM to those coded with SNOMED-CT. We included hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of pharmacological poisoning accompanied by external cause codes (X40-X44) indicating that the poisoning was accidental. For hospital admissions, we also identified whether the poisoning occurred at home or elsewhere, using the Y92 code. To evaluate management and outcomes, we described the recommended management (refer to hospital, stay at home, other) for each PIC call. For ED presentations, we explored the proportion of presentations arriving by ambulance services, the medical urgency (emergency, requiring care immediately or within 10 minutes; urgent, requiring attention within 30 min; semi-urgent, care required within 60 min; and non-urgent, needing care within 2 h) of each presentation, and proportion admitted to hospital. For hospital admissions, we examined the source of referral (from another hospital, from ED), length of stay, interventions performed, admissions to intensive care (ICU), re-admissions within 28 days, and in-hospital mortality. We also identified deaths within 30 days of discharge from hospital by linking hospital records to death registration data. Data analyses Given all data sources are independent, we conducted separate analyses for each health setting. Using the number of calls, presentations and admissions, we calculated annual, age- and sex-specific rates using the annual NSW estimated resident population aged 0–<5 years as the denominator [24]. We examined frequency, proportion and changes in pharmacological poisonings in each health setting by ICD10-AM categories, and identified the most common medicines implicated within each group. For PIC calls, we described these by pharmacological substance. We also calculated annual rates in poisonings for the most common medicines identified and compared characteristics of pharmacological poisonings between infancy (age <1 year) and early childhood (age 1–<5 years). We described management (including in-hospital treatment) and outcomes of poisonings in each health setting. To prevent individuals from being identified and preserve confidentiality, we did not present the precise number of children affected when the numbers were low (<5). Ethics approval The NSW Population and Health Services Research Ethics Committee and the Sydney Children's Hospitals Network Human Research Ethics Committee approved access to data, and the study. Results From 2007 to 2013, accidental pharmacological poisonings in children aged <5 years in NSW accounted for 67,816 calls to CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY 3 Table 1. Characteristics of calls to PIC, ED presentations and hospital admissions, for accidental pharmacological poisoning, NSW 2007–13. PIC N ¼ 67,816 Age (years) <1 1 2 3 4 Sex Male Female ED N ¼ 3901 Admissions N ¼ 2082 n % Ratea nb % Ratec n % Rate 7188 15,808 25,062 13,022 5434 10.6 23.3 37.0 19.2 8.0 106.1 238.1 383.9 201.8 85.2 341 1180 1459 648 273 8.7 30.2 37.4 16.6 7.0 10.0 35.8 45.4 20.5 8.7 120 501 885 418 158 5.8 24.1 42.5 20.1 7.6 1.8 7.5 13.6 6.5 2.5 33,834 30,312 49.9 44.7 201.0 190.2 2133 1768 54.7 45.3 25.1 22.0 1117 965 53.7 46.4 6.6 6.1 Rate per 10,000 children. Admissions, admissions to hospitals; ED, presentations to Emergency Departments; PIC, calls to Poisons Information Centre. a PIC rate: 1302 calls excluded: age unspecified, but known to be aged 1–<5 years. b ED – numbers of presentations coded to ICD10-AM. c ED rate has been extrapolated to all presentations, based on presentations coded to ICD10-AM. the PIC, an estimated 7739 ED presentations and 2082 hospital admissions (Table 1); an annual average of 9684 calls, 1106 ED presentations and 297 hospital admissions. Of children admitted to hospital, 74.7% of their poisonings occurred at home. Only a small proportion of children had >1 hospital admission for poisoning (1.3%). The distribution of calls, ED presentations and admissions by age was similar with agespecific rates highest among 2-year-old children (Table 1). The majority of PIC calls (n ¼ 65,958, 97.3%) involved exposure to a single medicine. Most calls (89.6%) were made by family or community members and 6.4% by a health professional from a hospital. Just over half (54.9%) of infants' exposures were defined as accidental ingestion, and 44.3% as therapeutic error. In contrast, 87.2% of poisonings for 1–<5 year olds, were recorded as accidental ingestion. The most common calls to the PIC (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1) related to “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics” (24.6% of calls); with paracetamol-containing medicines comprising three-fifths and ibuprofen-containing medicines implicated in one-third of these cases (Supplementary Table 2). This medicine class was also responsible for 12.8% of hospital admissions (the fourth most frequent medicine category for admissions to hospital). “Topical agents” (18.3% of calls) were the second-most common exposure resulting in calls, with 1 in 4 attributable to nappy rash preparations (Supplementary Table 2). Of ED presentations coded to ICD10-AM, over half (n ¼ 2114, 54.2%) were ascribed to the code representing 'diuretics, other and unspecified medicines' (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1). As such, further subclassification and analysis by medicine type was not possible. Four medicines groups were responsible for more than half of all hospital admissions (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 1): “antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic and anti-parkinsonism drugs”, “psychotropic drugs not elsewhere classified (NEC)”, “medicines primarily affecting the cardiovascular system”, and “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics”. Within each of these groups, respectively, four ICD10 subcategories, “benzodiazepines”, “other and unspecified antidepressants”, “uncategorised antihypertensives”, and “4-aminophenol derivatives” were the most common. Together, they accounted for over one-third of all admissions. When stratifying by age, calls to PIC concerning infants were most common for “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics” (33.5%) and for medicines designated for “topical application” (31.5%) (Table 2). Exposures to similar medicines were also common for children aged 1–<5 years, and resulted in 40% of calls to the PIC. As infants were rarely hospitalised (around nine per year), the pattern of admissions in children aged 1–<5 years (Table 2) was similar to that for all children in our study. Rates of calls to PIC declined from a high in 2008 to a low in 2013 (233 and 178 calls per 10,000 children, respectively), and a decline was also seen for hospital admissions (Table 3). Over the same period, presentations to ED remained stable at around 22–24 per 10,000 children. However, estimated rates of presentations classified as semi- or non-urgent increased from 3.9 to 8.5, urgent presentations were stable at around 12, while rates of presentations classified as emergency fell from 6.1 to 4.2 per 10,000 children. Annual rates of calls (per 10,000 children) to the PIC fell in two of the common medicine groups over the study period, 2007–13. “Topical agents” fell from 40 to 30 and “medicines acting on smooth and skeletal muscles and respiratory system” (particularly the anti-common cold medicines) halved from 30 to 14. However, there was little change in call rates for “non-opioid analgesics” and annual rates in calls for exposures to opioid medicines were low and stable at around 3–4 calls per 10,000 children per year. Similarly, rates in hospital admissions fell in three of the four medicine groups responsible for most admissions. For “antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic and antiparkinsonism drugs”, rates per 10,000 children declined from 1.3 to 0.6; for “psychotropic drugs NEC”, from 1.1 to 0.7; and for “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics”, from 1.2 to 0.6. Annual admission rates due to “medicines primarily affecting the cardiovascular system” were relatively stable at around 0.8 per 10,000 children. Of the calls to the PIC not originating from the hospital setting, 89.9% were advised to stay at home, and 6.2% were referred to hospital. Referrals to hospital most frequently involved exposures to “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics” (17.7%, almost all were paracetamolbased); “psychotropic drugs NEC” (13.4%, with a wide range of different medicines responsible); and “systemic and 4 J. C. BELL ET AL. Figure 1. Proportion of pharmacological poisonings in each setting, by medicine category (ICD10-AM T39-T50 codes). hematological agents, NEC” (12.6%, iron containing preparations implicated in one quarter of these). Of ED presentations, an estimated 15.3% arrived by ambulance services, 23.8% were classified as emergency and one-in-four were admitted as an inpatient. Most admissions to hospital presented first to ED (n ¼ 1758, 84.4%) and 8.5% were transferred from another hospital. The mean length of stay was less than one day (15.7 h). Interventions were reported for 201 (9.7%) admissions; with the majority (n ¼ 157) being an allied health intervention for social work. A small proportion (n ¼ 51, 2.4%) of children were admitted to ICU. The overall 28-day readmission rate during the study period was 2.5%. Children aged <1 year were more likely to be readmitted (6.5%), with a lower rate of readmissions (2%) for children 1–<5 years. There were too few (n <5) deaths in-hospital to report, and no child died within 30 days of discharge from hospital. Discussion This study, used concurrent state-wide data from three health services (PIC, ED presentations and hospital admissions), to provide a comprehensive evaluation of pharmacological poisonings and related health service use in young children in NSW, Australia, over a 7-year period. Information from each of these services highlights the value each provides to evaluating poisonings at the population level. For every admission to hospital, there were four ED presentations and 32 calls to the PIC (Figure 2). Rates for ED presentations classified as “emergency” and hospital admissions both declined, suggesting that there has been a true decline in more serious poisoning. Use of child resistant closures and safer storage of medicines may have contributed to this, but we have no direct evidence of this. A similar pattern in declining hospitalization rates has also been reported Australia-wide [29] and in England [20]. However, information about hospital admission rates from other countries is lacking. Decreased hospital admissions were accompanied by steady rates of ED presentations and falling rates of calls to the PIC. As ED presentations and calls to the PIC are subject to access and utilization, changes in rates of pharmacological poisonings in these health services are more difficult to interpret. For example, PIC utilization may reflect population awareness, rather than true incidence of poisoning [30]. CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY 5 Table 2. Pharmacological poisonings during infancy and early childhood, by medicine category (ICD10-AM T39-T50 codes), NSW PIC and hospital admissions 2007–2013. Infancy (<1 year) PICa N ¼ 7118 Systemic antibiotics Other systemic anti-infectives and antiparasitics Hormones and their synthetic substitutes and antagonists, NEC Nonopioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics Narcotics and psychodysleptics (hallucinogens) Anaesthetics and therapeutic gases Antiepileptic, sedative-hypnotic and antiparkinsonism drugs Psychotropic drugs, NEC Drugs primarily affecting the autonomic nervous system Primarily systemic and hematological agents, NEC Agents primarily affecting the cardiovascular system Agents primarily affecting the gastrointestinal system Agents primarily acting on smooth and skeletal muscles and the respiratory system Topical agents primarily affecting skin and mucous membrane and by ophthalmological, otorhinolaryngological and dental drugs Diuretics and other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances Early childhood (1–<5 years) n % n 323 24 186 4.5 0.3 2.6 b 2385 63 33.5 0.9 19 8 15.8 6.7 54 115 60 263 61 360 629 0.8 1.6 0.8 3.7 0.9 5.1 8.8 6 14 10 8 10 5.0 11.7 8.3 6.7 8.3 2243 31.5 11 348 4.9 16 b PICa N ¼ 58,840 Admissions N ¼ 120 % N % 3132 1109 5369 5.3 1.8 9.1 7 18 75 0.4 0.9 3.8 13,846 1162 55 1470 2506 881 5605 1727 1712 6743 23.5 2.0 0.1 2.5 4.3 1.5 9.5 2.9 2.9 11.5 248 122 8 322 276 150 157 258 29 67 12.6 6.2 0.4 16.4 14.1 7.7 8.0 13.1 1.5 3.4 9.2 9824 16.7 86 4.4 13.3 3699 6.3 139 7.1 % b b b b b n Admissions N ¼ 1962 NEC, not elsewhere classified. a PIC ¼ single pharmacological exposures. b Results for cells with numbers 5 suppressed. Table 3. Annual ratesa of calls to PIC, presentations to ED and hospital admissions for pharmacological poisonings, per 10,000 children aged 0–<5 years, NSW. EDb PIC Admissions Year n Rate n Rate n Rate 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 9743 10,583 10,170 9773 9327 9554 8666 220.0 233.0 218.3 206.1 197.0 199.0 178.1 977 1231 1132 1103 1041 1074 1181 22.1 27.1 24.3 23.3 22.0 22.4 24.3 353 359 379 271 220 249 251 8.0 7.9 8.1 5.7 4.6 5.2 5.2 Admissions, admissions to hospitals; ED, presentations to Emergency Departments; PIC, calls to Poisons Information Centre. a Rate per 10,000 children. b Numbers and rates of presentations to ED are extrapolated, based on presentations coded to ICD10-AM. Variations in rates over time may also reflect variations in case ascertainment—the fall in rate of calls to the PIC may indicate fewer poisonings, or may be related to less frequent use over time. During our study period, three national 24 h/7 days primary healthcare triage helplines were established (2007, 2010, 2011) [31], and these may have contributed to lower numbers of calls in the later years of our study. Data from 2014 indicated that of help-line medication-related calls, only 3.3% were referred to a PIC [32]. Calls to poisons centres have been shown to improve triage, allowing home management of many unintentional exposures, thereby reducing the number of people entering the health care system [33,34] and health care expenses [35,36]. In our study, the decrease in rates of calls to the PIC coincided with steady rates of ED presentations, but increasing rates of semi- or non-urgent presentations, suggesting that families may be bypassing Figure 2. Pharmacological poisonings pyramid, NSW 2007–2013. referral to the PIC, and attending ED as their first contact with the health system. In the USA, inability to speak English well, Black/African American race, and lower parental educational levels are associated with lower penetrance of regional poisons centres [30]. Similar factors may need to be targeted in NSW to focus families' attention on the benefits of triage by the PIC. We found exposure to “non-opioid analgesics, antipyretics and antirheumatics” to be the leading source of pharmacological poisoning for young children. While admission rates in Australia for these medicines have been falling for over 10 years, these medicines remain predominant, as they do in other countries [2,11,37]. The use of paracetamol, the most common analgesic of this group is ubiquitous, and for children, various forms and strengths exist [38]. While therapeutic doses are very safe, unintentional exposure at a high dose may induce severe toxic effects [38]. 6 J. C. BELL ET AL. While the decline in hospital admissions is encouraging, each year in NSW there are still approximately 10,000 children unintentionally exposed to pharmaceutical medicines, leading to around 250 hospital admissions. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposures and poisonings in children are strongly correlated with adult medication prescriptions [10,39]. While admissions in early childhood for three of the four major contributors to hospital admissions have fallen in NSW, admissions related to medicines affecting the cardiovascular system (such as statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II receptor antagonists) have not. Of note, 8 of the top 10 subsidized medicines dispensed in Australia belong in this category [40]. In the USA, the increased prescription use of opioids has coincided with a large increase in opioid poisonings in children, and children's opioid poisonings are now the most frequent medicine implicated in hospitalizations for pharmacological poisonings [14,23]. In contrast, opioid poisonings were low in our study. As changes in medicines use occur within the Australian health system (for example, the increasing use of opioids) [41], we need to continue to monitor available data sources for any changes in childhood poisonings. A number of local and international initiatives are underway to optimize preventive strategies [42–44]. Continuing to educate caregivers, as well as improving methods to ensure accurate doses can be measured and administered—for example consistent volume measures for all liquid medicines may reduce likelihood of error [43,45]. Although child resistant closures on bottle of medicines have reduced unintentional poisonings in children [46], new forms of packaging, such as flow restrictors for liquid formulations and double packaging of pills in blister packs within child-resistant containers, or single dose or tablet dispensing packs may further reduce accidental poisonings [1,46]. Limiting new safety features to medicines that are both commonly available in the community and most toxic may limit the cost and inconvenience to adults [1]. We have found no other study describing the total population burden of pharmacological poisonings across three levels of the health care system, using complementary data sources covering the same time period. The very small number of calls for NSW children handled by another poisons centre for seven nights (midnight-6am) in every 2 weeks is unlikely to have underestimated numbers and rates of calls, and unlikely to have biased our results. While ED data coverage is comprehensive, it is not complete, and the lack of data from the few public hospitals not participating in the ED data collection may have biased ED results. While nearly all ED presentations in NSW were included in our data, around 50% were coded using SMOMED-CT. We have assumed that the rates of ED presentations for pharmacological poisoning occurring in hospitals using ICD10-AM coding were the same as those in hospitals using SNOMED-CT coding, but this may not be the case. In addition, ED data were coded by staff in ED and this may have contributed to the large proportion of medicines categorized as “diuretics and other and unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances”, thus limiting our ability to investigate medicines implicated in ED presentations. This lack of detail about the medicines involved limits the ED setting for pharmacological poisoning surveillance. In addition, ED poisonings may be underestimated if coded as symptoms and signs without a diagnosis (for example, nausea and vomiting) rather than as pharmaceutical poisoning, leading to an underestimation of poisonings, and potential under-ascertainment of admissions after ED presentation. The ICD10-AM coding system, on which our medicine categories were based, is in wide use, but is not ideal for surveillance of pharmacological poisonings. While reporting of some medicines may be accurate [47], many newer medicines, and medicines in common use with potentially serious consequences if used inappropriately, are grouped without a specific category. For example, newer medicines such as sertraline, venlafaxine, and fluoxetine are not identifiable under the current ICD10 coding system (Supplementary Table 2). In other subcategories, medicines with different pharmacological actions are grouped together, such as antacids with anti-gastric secretion medicines, and fibrates with statins. In addition, the category of diuretics and other unspecified drugs, medicaments and biological substances is broad, including a wide range of pharmacological substances with a variety of pharmacological actions and clinical uses. While newer classification systems have been proposed [48,49], these medicine-specific coding systems are not applicable to all medicine types. Conclusions Using data from three health settings managing pharmacological poisonings, our study provides a comprehensive picture of early childhood poisonings. The decline in accidental pharmacological poisonings, especially in severe poisonings measured by hospital admissions and emergency ED presentations is encouraging. However, it may be off-set by the increased use of ED for semi- and non-urgent cases. In NSW specifically, use of the PIC for pharmacological poisonings triage needs to be encouraged to reduce possible unnecessary ED presentations for less severe poisonings. Future studies should explore whether these falling rates are seen across all population subgroups. Our findings highlight the importance of monitoring pharmacological poisonings using more than one data source, as results based on a single source may be misleading. Despite improvements, pharmacological poisonings in young children remain a problem and ongoing targeted strategies to reduce therapeutic errors and access to medicines by young children are needed. Acknowledgements This research was supported by the use of population data from the NSW Ministry of Health and the NSW Poisons Information Centre. The authors thank both the NSW Ministry of Health and the NSW Poisons Information Centre for providing access to data, and the NSW Centre for Health Record Linkage for linking the datasets. The findings and views reported in this study, however, are those of the authors and should not CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY be attributed to the NSW Ministry of Health or the NSW Poisons Information Centre. [12] [13] Disclosure statement Annette Katelaris is a co-inventor and owner of Juno Childsafe, a childproof bag for medications. No potential conflict of interest was reported by other authors. [14] [15] Funding Mr Bentley was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award Scholarship, Sydney University Merit Award, and a Northern Clinical School Scholarship Award. Dr Cairns and Prof Buckley were supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Program grant (APP1055176) and Prof Nassar was supported by a National Health and Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship (APP1067066). ORCID Jane C. Bell http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6940-6517 Jason P. Bentley http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0363-8782 Rose Cairns http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8946-5079 http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6326-4711 Nicholas A. Buckley Annette Katelaris http://orcid.org/0000-0002-0482-4854 Sallie-Anne Pearson http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7137-6855 Natasha Nassar http://orcid.org/0000-0002-3720-9655 [16] [17] [18] [19] [20] [21] [22] References [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] Bond GR, Woodward RW, Ho M. The growing impact of pediatric pharmaceutical poisoning. J Pediatr. 2012;160:265–270.e1. Lovegrove MC, Weidle NJ, Budnitz DS. Trends in emergency department visits for unsupervised pediatric medication exposures, 2004-2013. Pediatrics 2015;136:e821–e829. Smith MD, Spiller HA, Casavant MJ, et al. Out-of-hospital medication errors among young children in the United States, 20022012. Pediatrics 2014;134:867–876. Anderson M, Hawkins L, Eddleston M, et al. Severe and fatal pharmaceutical poisoning in young children in the UK. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:653–656. Lowry JA, Fine JS, Calello DP, et al. Pediatric fatality review of the 2013 National Poison Database System (NPDS): focus on intent. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015;53:79–81. Mowry JB, Spyker DA, Brooks DE, et al. 2014 annual report of the american association of poison control centers' national poison data system (NPDS): 32nd annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2015;53:962–1147. Bentur Y, Lurie Y, Cahana A, et al. Poisoning in Israel: annual report of the Israel poison information center, 2012. Isr Med Assoc J. 2014;16:686–692. Nguyen MB, Pizon AF, Branas CC, et al. Regional variations in pediatric medication exposure: spatial analysis of poison center utilization in western Pennsylvania. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:47–52. Dart RC, Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, et al. Poisoning in the United States: 2012 emergency medicine report of the national poison data system. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65:416–422. Bailey JE, Campagna E, Dart RC. The underrecognized toll of prescription opioid abuse on young children. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53:419–424. Azab SM, Hirshon JM, Hayes BD, et al. Epidemiology of acute poisoning in children presenting to the poisoning treatment center at Ain Shams University in Cairo, Egypt, 2009-2013. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2016;54:20–26. [23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] 7 Ahmed A, AlJamal AN, Mohamed Ibrahim MI, et al. Poisoning emergency visits among children: a 3-year retrospective study in Qatar. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:104. Cohen AL, Budnitz DS, Weidenbach KN, et al. National surveillance of emergency department visits for outpatient adverse drug events in children and adolescents. J Pediatr. 2008;152:416–421. Lovegrove MC, Mathew J, Hampp C, et al. Emergency hospitalizations for unsupervised prescription medication ingestions by young children. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1009–e1016. Li C, Martin BC. Trends in emergency department visits attributable to acetaminophen overdoses in the United States: 19932007. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:810–818. Willy M, Kelly JP, Nourjah P, et al. Emergency department visits attributed to selected analgesics, United States, 2004-2005. Pharmacoepidem Drug Safe. 2009;18:188–195. Nalliah RP, Anderson IM, Lee MK, et al. Children in the United States make close to 200,000 emergency department visits due to poisoning each year. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:453–457. Naun CA, Olsen CS, Dean JM, et al. Can poison control data be used for pharmaceutical poisoning surveillance? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18:225–231. Setlik J, Ho M, Bond GR. Emergency department use after pediatric pharmaceutical ingestion: comparison of two national databases. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:64–67. Mbeledogu CN, Cecil EV, Millett C, et al. Hospital admissions for unintentional poisoning in preschool children in England; 20002011. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100:180–182. Kim K, Choi JW, Park M, et al. A nationwide study of patients hospitalised for poisoning in Korea based on Korea national hospital discharge in-depth injury survey data from 2005 to 2009. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e008823. Groom L, Kendrick D, Coupland C, et al. Inequalities in hospital admission rates for unintentional poisoning in young children. Inj Prev. 2006;12:166–170. Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Ryan SA, et al. National trends in hospitalizations for opioid poisonings among children and adolescents, 1997 to 2012. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:1195–1201. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Australian Demographic Statistics. Canberra: Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2017. NSW Poisons Information Centre. 2016. Available from: http:// www.poisonsinfo.nsw.gov.au/ Centre for Epidemiology and Evidence. Health Stats (SAPHaRI) Sydney: NSW Ministry of Health; 2017. Available from: http://www.healthstats.nsw.gov.au/Indicator/beh_alcedage/beh_ alcedage The International Health Terminology Standards Development Organisation. SNOMED CT: IHTSDO. 2016. Available from: http:// www.ihtsdo.org/snomed-ct Mitchell RJ, Bambach MR, Muscatello D, et al. Can SNOMED CT as implemented in New South Wales, Australia be used for road trauma injury surveillance in emergency departments? Him J. 2013;42:4–8. Pointer S, Trends in hospitalised injury, Australia 1999–00 to 2012–13. Injury research and statistics series No. 95. Cat. no. INJCAT 171. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2015. Litovitz T, Benson BE, Youniss J, et al. Determinants of U.S. poison center utilization. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2010;48:449–457. healthdirect Australia. healthdirect. 2017. Available from: https:// about.healthdirect.gov.au/our-history Li L, Lake R, Raban MZ, et al. Medication-related calls received by a national telenursing triage and advice service in Australia: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:197. Zaloshnja E, Miller T, Jones P, et al. The impact of poison control centers on poisoning-related visits to EDs-United States, 2003. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:310–315. Jackson BF, McCain JE, Nichols MH, et al. Emergency department poisoning visits in children younger than 6 years: comparing referrals by a regional poison control center to referrals by other sources. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28:1343–1347. 8 J. C. BELL ET AL. [35] Lewin Group. Value of the poison center system: Lewin Group report. Falls Church, VA: Lewin Group; 2012. West J, Taylor L, Smith N, et al. Cost savings through community access to the NSW poisons information centre. Aust Health Rev. 1987;10:238–247. Ontario Poison Centre. Current Top 10 - Children Under Five Toronto: Hospital for Sick Children; 2017. Available from: http:// www.ontariopoisoncentre.ca/common-poisons/Current%20Top %2010/Top-10-Lists.aspx Mund ME, Quarcoo D, Gyo C, et al. Paracetamol as a toxic substance for children: aspects of legislation in selected countries. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2015;10:43. Burghardt LC, Ayers JW, Brownstein JS, et al. Adult prescription drug use and pediatric medication exposures and poisonings. Pediatrics 2013;132:18–27. Australian Prescriber. Top 10 drugs. Aust Prescr 2016; 39:135. Drug utilisation sub-committee (DUSC). Opioid analgesics: overview. Canberra: Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme; 2014. Kidsafe. Poisoning Prevention Sydney: KidSafe NSW Inc. 2017. Available from: http://www.kidsafensw.org/home-community/poisoning-prevention/ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The PROTECT Initiative: Advancing Children’s Medication Safety: CDC. 2017. [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [44] [45] [46] [47] [48] [49] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/MedicationSafety/protect/ protect_Initiative.html US Food and Drug Administration. Safe use of over-the-counter pain relievers and fever reducers: US FDA. 2017. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/ResourcesForYou/Consumers/Buying Using MedicineSafely/UnderstandingOver-the-CounterMedicines/ SafeUseofOver-the-CounterPainRelieversandFeverReducers/ ucm164977.htm AAP Committee on Drugs. Metric units and the preferred dosing of orally administered liquid medications. Pediatrics 2015; 135:784–787. Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC. The last mile: taking the final steps in preventing pediatric pharmaceutical poisonings. J Pediatr. 2012;160:190–192. de Achaval S, Feudtner C, Palla S, et al. Validation of ICD-9-CM codes for identification of acetaminophen-related emergency department visits in a large pediatric hospital. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:72. Caraci F, Enna SJ, Zohar J, et al. A new nomenclature for classifying psychotropic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83: 1614–1616. Ghaemi SN. A new nomenclature for psychotropic drugs. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35:428–433.