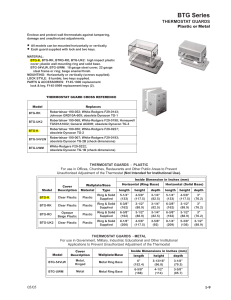

IDEAS AND INNOVATIONS Use of Tranexamic Acid to Reduce Blood Loss in Liposuction Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/plasreconsurg by SwCoVAoBS51l4iN6frVvMnGapRqfmlg5Kvxdqf5eMc5ZqI6GpAnKIChglx/KgiWJOnc4w3AxheVY0vNaE1wb0tswdcrM4tSmK/YWhu8w+h7aGqvihHjSBLvVjLlubB6prNzbTkhw3OI= on 11/27/2021 Alvaro Luiz Cansancao, M.D. Alexandra Condé-Green, M.D. Joshua A. David, B.S. Bethania Cansancao, M.D. Rafael A. Vidigal, M.D. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Newark, N.J.; and New York, N.Y. Background: The use of tranexamic acid for blood loss prevention has gained popularity in many specialties, including plastic surgery. However, its use in liposuction has not been studied. The authors present a prospective, doubleblind, nonrandomized study evaluating the efficacy of tranexamic acid in reducing perioperative blood loss during liposuction. Methods: Twenty women undergoing liposuction were divided into two cohorts. Group 1 (n = 10) received a standard dose of 10 mg/kg of tranexamic acid intravenously in the preoperative and postoperative periods, whereas group 2 (n = 10) received a placebo. Patient hematocrit levels were evaluated preoperatively and postoperatively. Blood volume in the infranatant of the lipoaspirate was also measured; t tests were used for statistical analysis. Results: Age, body mass index, and volume of lipoaspirate were comparable between the two cohorts. The volume of blood loss for every liter of lipoaspirate was 56.2 percent less in the tranexamic group compared with the control group (p < 0.001). Hematocrit levels at day 7 postoperatively were 48 percent less in group 1 compared with group 2 (p = 0.001). Furthermore, a 1 percent drop in the hematocrit level was found after liposuction of 812 ± 432 ml in group 1 and 379 ± 204 ml in group 2. Thus, the use of tranexamic acid could allow for aspiration of 114 percent more fat, with comparable variation in hematocrit levels. Conclusions: Tranexamic acid has been shown to be effective for minimizing perioperative blood loss in liposuction. Further large randomized controlled studies are required to corroborate this effect. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 141: 1132, 2018.) CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE: Therapeutic, II. L iposuction remains one of the most commonly performed aesthetic surgical procedures, and its popularity increases every year.1 However, since its inception, justified concerns regarding patient safety have generated limits on the volume of fat that can be aspirated. These limitations are largely influenced by the hemodynamic fluctuations and blood loss that can occur during liposuction.2 Tranexamic acid is an antifibrinolytic agent that competitively From the Department of Plastic Surgery, Universidade ­Iguaçu, Hospital da Plástica; the Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of General Surgery, Rutgers New Jersey Medical School; and the Hansjörg Wyss Department of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, New York University Langone Medical Center. Received for publication July 10, 2017; accepted November 15, 2017. Presented at Plastic Surgery The Meeting 2015, American Society of Plastic Surgeons Annual Meeting, in Boston, Massachusetts, October 16 through 20, 2015. Copyright © 2018 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004282 1132 inhibits the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, thereby preventing the binding and degradation of fibrin, and preserving the framework of its matrix structure.3 Studies in various medical specialties, such as orthopedic surgery,4 cardiology,5 and gynecology,6 have shown that it can reduce blood loss and transfusion requirements. In recent years, the surgical application of tranexamic acid for minimization of blood loss has undergone a revival, and its use has been coopted by plastic surgeons for reduction of intraoperative bleeding. This has proven particularly effective in burns7 and in craniomaxillofacial8 and aesthetic procedures. Although its use in liposuction has been cited by some publications,9,10 its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss during liposuction has not yet been studied. Disclosure: The authors declare no conflicts of ­interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article. www.PRSJournal.com Copyright © 2018 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 141, Number 5 • Tranexamic Acid for Reducing Blood Loss Fig. 1. Klein equation to calculate the volume of whole blood aspirated by liposuction. PATIENTS AND METHODS Here, we present a prospective, double-blind, nonrandomized study evaluating the effects of tranexamic acid on blood loss of patients undergoing liposuction. The institutional review board at our institution approved the study. Twenty women undergoing liposuction were divided into two cohorts. The experimental group (group 1, n = 10) received a standard intravenous dose of 10 mg/ kg of tranexamic acid, 30 minutes preoperatively and postoperatively (the recommended dosage), whereas the control group (group 2, n = 10) received normal saline intravenously. Exclusion criteria included patients younger than 18 and older than 65 years; body mass index greater than 35 kg/ m2; current smoking; a diagnosis of diabetes or renal failure; an American Society of Anesthesiologists score greater than or equal to 3; and current anticoagulation or corticoid therapy. All operations were performed under locoregional anesthesia, and a solution of normal saline and epinephrine at 1:500,000 was infiltrated subcutaneously according to the superwet technique. Power-assisted liposuction was performed 10 minutes after infiltration. Intraoperative hydration was performed as follows: lactated Ringer solution was administered at a rate of 1:1 per volume of expected supernatant (fat). Fifty percent was injected during hour 1 of the procedure, 25 percent during hour 2, and 25 percent during hour 3. Postoperatively, lactated Ringer solution was again administered at a rate of 500 ml/ hour during the first 6 hours, and 250 ml/hour in the subsequent 6 hours. Patient hematocrit levels were evaluated preoperatively and on day 7 postoperatively. The blood volume of the total lipoaspirate (supernatant and infranatant) was measured according to the Klein equation11 (Fig. 1). The G*Power 3.1 statistical package was used for post hoc power analysis, and nonparametric WilcoxonMann-Whitney tests were used to compare means between the groups. RESULTS Patient characteristics were comparable between the two cohorts. Patients in the tranexamic acid group had a mean age of 40.7 years (range, 24 to 54 years) and patients in the control group had a mean age of 36.2 years (range, 28 to 51 years). The mean body mass index was 28.3 kg/m2 (range, 24 to 31 kg/m2) in group 1 and 25.4 kg/m2 (range, 19 to 32 kg/m2) in group 2. The average supernatant (fat) volumes were 4280 ml and 3715 ml, respectively, corresponding to 5.8 percent and 5.4 percent, respectively, of patient body weight. The duration of all procedures was approximately 3 hours (range, 2.5 to 3.0 hours). All patients were discharged to home on postoperative day 1. None of the patients exhibited side effects from the use of tranexamic acid. Our results show that despite aspiration of similar absolute and relative volumes from both patient cohorts, the total volume of blood in the total lipoaspirate according to the Klein equation11 was 37.7 ml in group 1 and 59.9 ml in group 2, representing 37 percent less perioperative blood loss in patients who received tranexamic acid (p < 0.05).12 The volume of blood loss for every liter of supernatant was 8.8 ml and 20.1 ml in groups 1 and 2, respectively, representing 56.2 percent less blood loss per liter of supernatant in group 1 (p = 0.001) (Table 1). There was a 1.3 percent drop in the hematocrit level per liter of supernatant in group 1 patients, and 2.7 percent in group 2, representing a drop in hematocrit that was 48 percent less in the hematocrit level of patients who received tranexamic acid (p < 0.03). Therefore, a 1 percent drop in the hematocrit level was found after liposuction of 812 ± 432 ml in group 1 and 379 ± 204 ml in group 2 (Table 2). Thus, the use of tranexamic acid could allow for aspiration of 114 percent more fat despite comparable variations in hematocrit levels (p < 0.009). DISCUSSION First introduced as a treatment for menorrhagia and hereditary bleeding disorders in the 1960s, tranexamic acid has been rapidly adopted for use in a wide variety of conditions and procedures. Administration of tranexamic acid—locally, orally or intravenously—has been shown to minimize hematoma-related complications in rhinoplasty,13 rhytidectomy,14 and reduction mammaplasty.15 In addition to its proven hemostatic effects, it is generally well tolerated; mild diarrhea and nausea 1133 Copyright © 2018 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery • May 2018 Table 1. Comparative Results of Blood Volume in the Lipoaspirate of Groups 1 and 2 No. of patients Aspirated volume, liters Percentage of body weight aspirated Blood volume in aspirate, ml Volume of blood per liter of aspirate, ml/liter Group 1 Group 2 p 10 4.280 ± 1.434 5.8 ± 1.8 37.7 ± 15.5 8.8 ± 2.0 10 3.715 ± 1.693 5.4 ± 1.7 59.9 ± 25.1 20.1 ± 7.6 0.3615 0.6443 0.0410 0.0010 Table 2. Preoperative and Postoperative Hematocrit Levels of Groups 1 and 2 Initial Hct, g/dl Postoperative Hct, g/dl Hct reduction, g/dl Hct reduction per aspirated liter, g/dl/liter Aspirated volume to reduce Hct by 1%, ml Group 1 Group 2 p 38.7 ± 4.4 32.9 ± 1.2 6.4 ± 2.6 1.3 ± 0.7 812 ± 432 39.3 ± 2.3 31.0 ± 2.8 7.9 ± 2.2 2.7 ± 1.1 379.2 ± 203.8 0.5407 0.0850 0.1807 0.0219 0.0089 Hct, hematocrit. are the most common side effects.16 Because of the theoretical risks associated with fibrinolytic inhibition, a history of venous or arterial thrombosis is considered a contraindication to the use of tranexamic acid.17,18 However, despite isolated case reports of cerebral19 and arterial20 thrombosis, controlled randomized studies in cardiac21 and orthopedic surgery,22 and large retrospective studies among pregnant women—who are already at an increased risk for thrombosis—have failed to confirm any such association.23 To our knowledge, this is the first prospective comparative study displaying the efficacy of tranexamic acid in reducing blood loss in liposuction. Although our study was nonrandomized, with a small sample size, we found a significant decrease in the drop of hematocrit levels and volume blood loss in the supernatant of patients who received tranexamic acid without any associated complications. CONCLUSIONS Tranexamic acid has proven to be an effective and safe adjunct for minimizing perioperative blood loss during liposuction. As this inveterate drug expands into new arenas within plastic surgery, further large randomized controlled studies are required to corroborate its efficacy and superior patient profile safety. Alvaro Luiz Cansancao, M.D. Avenida das Americas 3200, Sala 212 Rio de Janeiro, Brazil 22640-102 [email protected] 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. REFERENCES 1. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2016 plastic surgery statistics report. Available at: https://d2wirczt3b6wjm. 15. cloudfront.net/News/Statistics/2016/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2016.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2017. Cansanção AL, Cansanção AJ, Cansanção BP, Vidigal RA. Lipoabdominoplasty in obese patients: Is it safe? Has good results? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(Suppl):93–94. Rajesparan K, Biant LC, Ahmad M, Field RE. The effect of an intravenous bolus of tranexamic acid on blood loss in total hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:776–783. Amer KM, Rehman S, Amer K, Haydel C. Efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in orthopaedic fracture surgery: A metaanalysis and systematic literature review. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31:520–525. Horrow JC, Hlavacek J, Strong MD, et al. Prophylactic tranexamic acid decreases bleeding after cardiac operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1990;99:70–74. Gai MY, Wu LF, Su QF, Tatsumoto K. Clinical observation of blood loss reduced by tranexamic acid during and after caesarian section: A multi-center, randomized trial. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;112:154–157. Tang YM, Chapman TW, Brooks P. Use of tranexamic acid to reduce bleeding in burns surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65:684–686. Murphy GR, Glass GE, Jain A. The efficacy and safety of tranexamic acid in cranio-maxillofacial and plastic surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2016;27:374–379. Nair AS, Sriprakash K, Nirale AM, et al. Large volume liposuction: Perioperative considerations. Int J Sci Res Publications 2013;3:1–4. Nair AS, Verma S. Use of tranexamic acid in megaliposuction. Int J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2015;7:8. Klein JA. Tumescent technique for local anesthesia improves safety in large-volume liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:1085–1098. Cansanção AL, Cansanção AJ, Cansanção BP, Vidigal RA. Effect of tranexamic acid in bleeding control in liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136(Suppl):80. Ors S, Ozkose M. Late postoperative massive bleeding in septorhinoplasty: A prospective study. Plast Surg (Oakv.) 2016;24:96–98. Butz DR, Geldner PD. The use of tranexamic acid in rhytidectomy patients. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4:e716. Ausen K, Fossmark R, Spigset O, Pleym H. Randomized clinical trial of topical tranexamic acid after reduction mammoplasty. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1348–1353. 1134 Copyright © 2018 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited. Volume 141, Number 5 • Tranexamic Acid for Reducing Blood Loss 16. Verstraete M. Clinical application of inhibitors of fibrinolysis. Drugs 1985;29:236–261. 17. Dunn CJ, Goa KL. Tranexamic acid: A review of its use in surgery and other indications. Drugs 1999;57:1005–1032. 18. Tengborn L, Blombäck M, Berntorp E. Tranexamic acid: An old drug still going strong and making a revival. Thromb Res. 2015;135:231–242. 19. Rydin E, Lundberg PO. Tranexamic acid and intracranial thrombosis. Lancet 1976;2:49. 20. Davies D, Howell DA. Tranexamic acid and arterial thrombosis. Lancet 1977;1:49. 21. Coffey A, Pittmam J, Halbrook H, Fehrenbacher J, Beckman D, Hormuth D. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce postoperative bleeding following cardiac surgery: A double-blind randomized trial. Am Surg. 1995;61:566–568. 22. Benoni G, Fredin H. Fibrinolytic inhibition with tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after knee arthroplasty: A prospective, randomised, double-blind study of 86 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:434–440. 23. Lindoff C, Rybo G, Astedt B. Treatment with tranexamic acid during pregnancy, and the risk of thrombo-embolic complications. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:238–240. 1135 Copyright © 2018 American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.