FoCUS vs. Echocardiography: LVSF Assessment in Internal Medicine

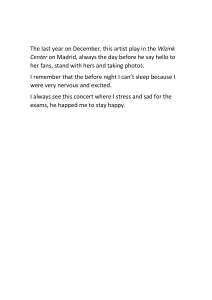

Anuncio

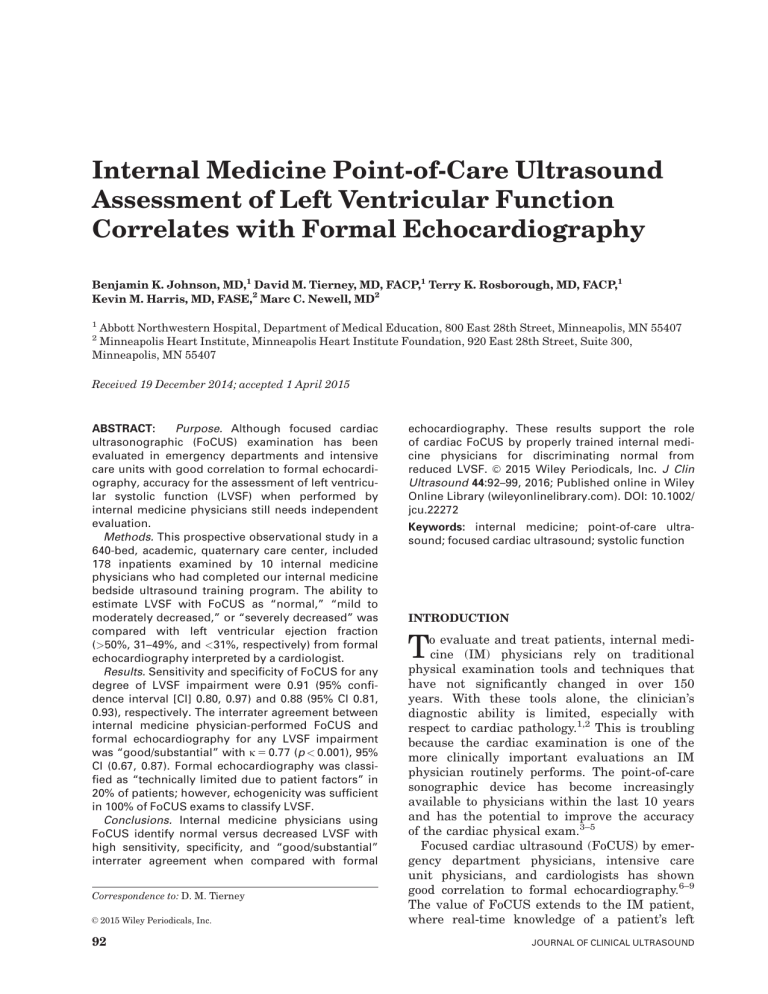

Internal Medicine Point-of-Care Ultrasound Assessment of Left Ventricular Function Correlates with Formal Echocardiography Benjamin K. Johnson, MD,1 David M. Tierney, MD, FACP,1 Terry K. Rosborough, MD, FACP,1 Kevin M. Harris, MD, FASE,2 Marc C. Newell, MD2 1 Abbott Northwestern Hospital, Department of Medical Education, 800 East 28th Street, Minneapolis, MN 55407 Minneapolis Heart Institute, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation, 920 East 28th Street, Suite 300, Minneapolis, MN 55407 2 Received 19 December 2014; accepted 1 April 2015 ABSTRACT: Purpose. Although focused cardiac ultrasonographic (FoCUS) examination has been evaluated in emergency departments and intensive care units with good correlation to formal echocardiography, accuracy for the assessment of left ventricular systolic function (LVSF) when performed by internal medicine physicians still needs independent evaluation. Methods. This prospective observational study in a 640-bed, academic, quaternary care center, included 178 inpatients examined by 10 internal medicine physicians who had completed our internal medicine bedside ultrasound training program. The ability to estimate LVSF with FoCUS as “normal,” “mild to moderately decreased,” or “severely decreased” was compared with left ventricular ejection fraction (>50%, 31–49%, and <31%, respectively) from formal echocardiography interpreted by a cardiologist. Results. Sensitivity and specificity of FoCUS for any degree of LVSF impairment were 0.91 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.80, 0.97) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.81, 0.93), respectively. The interrater agreement between internal medicine physician-performed FoCUS and formal echocardiography for any LVSF impairment was “good/substantial” with j 5 0.77 (p < 0.001), 95% CI (0.67, 0.87). Formal echocardiography was classified as “technically limited due to patient factors” in 20% of patients; however, echogenicity was sufficient in 100% of FoCUS exams to classify LVSF. Conclusions. Internal medicine physicians using FoCUS identify normal versus decreased LVSF with high sensitivity, specificity, and “good/substantial” interrater agreement when compared with formal Correspondence to: D. M. Tierney C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. V 92 echocardiography. These results support the role of cardiac FoCUS by properly trained internal medicine physicians for discriminating normal from C 2015 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. J Clin reduced LVSF. V Ultrasound 44:92–99, 2016; Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/ jcu.22272 Keywords: internal medicine; point-of-care ultrasound; focused cardiac ultrasound; systolic function INTRODUCTION T o evaluate and treat patients, internal medicine (IM) physicians rely on traditional physical examination tools and techniques that have not significantly changed in over 150 years. With these tools alone, the clinician’s diagnostic ability is limited, especially with respect to cardiac pathology.1,2 This is troubling because the cardiac examination is one of the more clinically important evaluations an IM physician routinely performs. The point-of-care sonographic device has become increasingly available to physicians within the last 10 years and has the potential to improve the accuracy of the cardiac physical exam.3–5 Focused cardiac ultrasound (FoCUS) by emergency department physicians, intensive care unit physicians, and cardiologists has shown good correlation to formal echocardiography.6–9 The value of FoCUS extends to the IM patient, where real-time knowledge of a patient’s left JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ULTRASOUND INTERNIST ASSESSMENT OF SYSTOLIC FUNCTION ventricular systolic function (LVSF) can be helpful in determining the etiology of shock, hypotension, dyspnea, and other common syndromes.10–13 Prompt diagnosis of these entities among inpatients being cared for by IM physicians could lead to more rapid and accurate treatment. In addition, FoCUS could provide ongoing follow-up on a daily or hourly basis to monitor a patient’s physiology and tailor treatment in this patient population. Limited literature exists on FoCUS use by IM physicians and residents, and additional verification among various training models and patient populations is needed.14–17 This study evaluates the agreement between assessment of LVSF with FoCUS performed by IM physicians and formal echocardiography in a technically difficult inpatient population. MATERIALS AND METHODS This prospective observational study took place at a 640-bed, academic, university-affiliated, quaternary care center with approximately 40,000 inpatient admissions annually. The IM residency program has 33 residents, 22 full-time IM faculty, and 45 teaching hospitalists. The present study was approved by our institutional review board (Schulman Associates IRB, Inc., which has no affiliation with FujiFilm SonoSite, the manufacturer of the sonographic devices used in this study; Approval No. 201401371). Training The residency program instituted an internal medicine bedside ultrasound (the IMBUS program) curriculum in 2011. IM residents in their first year of training and faculty take part in a 1-week (40hour) training course focused on incorporation of bedside ultrasound into their physical exam, including pulmonary, cardiac (18 hours), abdominal, HEENT (head, eyes, ears, nose, and throat), musculoskeletal, and soft tissue ultrasound. The cardiac portion of the curriculum not only trained the user to characterize LVSF as mildly, moderately, or severely reduced based on visual estimation but also to identify volume status, pericardial disease, valvular disease, and structural heart disease. Following the IMBUS course, the resident is mentored at the bedside by a certified faculty member for all patient exams until the learner is certified to perform exams independently. Certification Certification within the FoCUS portion of the IMBUS curriculum requires (1) completion of VOL. 44, NO. 2, FEBRUARY 2016 the initial course, (2) completion of a minimum quantity of mentored FoCUS exams, followed by (3) a one-on-one assessment by the IMBUS program director using a checklist of criteria pertaining to technical image acquisition, interpretation, and appropriate clinical integration of findings. When all three of these mastery learning18,19 components are achieved, a physician receives FoCUS certification. The number of completed examinations performed by a physician at the time of certification in any given area such as “LVSF assessment” is variable but always above a set minimum. The mean number of cardiac exams for LVSF performed by certified mentors achieving their IMBUS cardiac certification prior to the initiation of the study was: total focused cardiac exams involving three to four views (parasternal long/short axis, apical 4/5 chamber, apical long axis, apical two-chamber, subxyphoid fourchamber) 5 44.4 exams (SD 5 2.0), exams with “normal” LVSF 5 20.3 (SD 5 1.8), exams with “mild/moderate” LVSF impairment 5 16.4 (SD 5 2.2), and exams with “severe” LVSF impairment 5 7.8 (SD 5 0.7). FoCUS Exams The FoCUS examination is a routine part of our inpatient care among patients admitted to the IM resident service. Patients included in the study consisted of a daytime convenience sample of patients with a broad range of comorbidities admitted to the IM resident service with clinical questions related to cardiac physiology who also underwent formal echocardiography within 48 hours. The FoCUS exams used in this study were on patients who already had a formal echo ordered or would have had a formal echo performed regardless of the FoCUS findings. Therefore, the FoCUS results did not influence the decision to order a formal echocardiogram. The patients had varying levels of acuity and were located throughout all parts of the hospital, including the general medical ward, intensive care unit, and telemetry units. The residents performing the FoCUS were blinded to results from any prior and current formal echocardiography. Of note, the physicians performing/interpreting the FoCUS were not blinded to the patient’s current clinical presentation. This is similar to a typical use environment for FoCUS, wherein the provider is aware of the clinical specifics around the examination. All of the residents who participated in the IMBUS program were informed that their work 93 JOHNSON ET AL TABLE 1 Patient’s Characteristics and Formal Echocardiography Findings Patient Characteristic Mean age (y) Age > 60 (%) Age range (y) Male sex (%) Obese (BMI > 30) (%) COPD (%) Median duration between FoCUS and formal echo (hours) Echo quality reported as technically limited (%) Formal echo LVEF findings (%) 30% 31–49% 50% n 5 178 70 77 21–100 51 34 19 19 20 15 17 68 Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FoCUS, focused cardiac ultrasound; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction. would be evaluated and used for research purposes. All FoCUS exams included in this study had one of 10 IMBUS-certified IM physicians present at the bedside. This certified physician was responsible for providing mentoring to ensure appropriate image acquisition and interpretation by the performing, noncertified resident. The physician’s ability to estimate LVSF with FoCUS as “normal,” “mild to moderately decreased,” or “severely decreased” was compared with formal cardiologist-interpreted echocardiography. The cardiologist-interpreted LVSF was reported as ejection fraction in percentage form. To compare this continuous data to the ordinal data obtained from FoCUS, the following scale, utilized by our echocardiography laboratory, was used: ejection fraction greater than or equal to 50% on formal echo was considered “normal”; ejection fraction of 31–49% was considered “mild to moderately reduced”; and ejection fraction less than or equal to 30% was considered “severely reduced.” Physicians performing the FoCUS exams were aware of the ejection fraction correlates to these three classification categories of LVSF. A board-certified cardiologist with a minimum of adult cardiovascular medicine core cardiology training (COCATS) Level II for echocardiography, in a lab with a Level III director, interpreted all formal echocardiograms and was blinded to the results of the FoCUS examination. The cardiologist reading the formal echocardiogram classified the formal study as technically “excellent/good,” “fair,” or “limited.” 94 Technology The FoCUS exams were performed with SonoSite NanoMaxx or SonoSite EDGE portable ultrasound systems equipped with a P21 (1–5MHz) phased-array transducer (FujiFilm SonoSite Inc., Bothell, WA). The formal echocardiograms were obtained using one of the following five devices: Siemens C512 Sequoia with 4V1c (2.25–4.25-MHz) transducer (Erlangen, Germany), Siemens SC2000 with 4V1c (2.25–4.25MHz) transducer, Philips IE33 with S5–1 or X5–1 (2.25–4.25-MHz) transducer (Amsterdam, Netherlands), GE Vivid I with 3S-RS (2.25– 4.25-MHz) transducer (Buckinghamshire, United Kingdom), or GE Vivid 7 with M4S (2.25–4.25-MHz) transducer. Statistics Sensitivity and specificity for FoCUS compared with the gold-standard formal cardiologistinterpreted echocardiography assessment of LVSF were calculated. Because of the high rate of agreement due to chance, Kappa (j) statistics were determined for LVSF assessment between FoCUS and formal echocardiography interpretation of “normal” versus “any LVSF impairment.” Agreement using j with linear weighting was also performed for assessment of LVSF between FoCUS and formal echocardiography in the individual categories of “normal,” “mild/moderately reduced,” and “severely reduced” LVSF (JMP, Version 10, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). As total disagreement about LVSF categories is clinically more important than disagreeing in small degrees, a linear weighted j measurement was also used to assess agreement between individual categories of LVSF and formal echocardiography. RESULTS There were 209 patients who underwent FoCUS and formal echocardiography over a 6-month study period. Thirty-one patients had formal echocardiograms that were performed more than 48 hours after FoCUS and were excluded. Therefore, 178 patients were included in the final analysis. Baseline characteristics for the 178 patients are shown in Table 1. The median time between FoCUS and formal echocardiography exams, as defined by completion time of FoCUS exam and start of formal echocardiogram, was 19 hours (interquartile range: 3–24 hours, range: 5 minutes to 47 hours). A significant proportion (20%) of the included exams were reported as “technically limited in quality secondary to JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ULTRASOUND INTERNIST ASSESSMENT OF SYSTOLIC FUNCTION FIGURE 1. Internal medicine bedside ultrasound qualitative assessment of left ventricular systolic function (LVSF) compared with formal echocardiography left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) (n 5 178). Formal echocardiography LVEF cutoffs (horizontal gray lines) were set as “normal 50%,” “mild/moderate dysfunction 31–49%,” “severe dysfunction 30%.” White data points represent “technically limited” formal studies per cardiologist interpretation. FoCUS, focused cardiac ultrasound. patient characteristics” on the formal echocardiogram report. The technical difficulty of FoCUS exams was not recorded; however, no patients were excluded because of an inability to assess LVSF with the FoCUS machine. The agreement and disagreement between FoCUS and formal echocardiography for each patient exam are graphically depicted in Figure 1. Sensitivity and specificity of FoCUS when compared with formal echocardiography for any LVSF impairment were 0.91 (95% confidence interval [CI] 0.80, 0.97) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.81, 0.93), respectively (Table 2). Agreement (j) between FoCUS exams and formal echocardiography for any LVSF impairment was “good/substantial”20,21 with j 5 0.77 (p < 0.0001, 95% CI [0.67, 0.87]). Agreement between individual categories of LVSF and formal echocardiography was also “good/substantial” with j 5 0.77 (p < 0.001, 95% CI [0.67, 0.87]). Agreement between FoCUS and formal echocardiography did not worsen with increasing duration between FoCUS and formal echocardiography when divided into quartiles of time between studies (Q1 [<3 hours]: j 5 0.74 [0.53, 0.96]; Q2 [3–19 hours]: j 5 0.64 [0.41, 0.87]; Q3 [19–24 hours]: j 5 0.78 [0.59, 0.96]; Q4 [>24 hours]: j 5 0.93 [0.8, 1.0]). DISCUSSION Real-time knowledge of a patient’s LVSF is clinically valuable information in many scenarios VOL. 44, NO. 2, FEBRUARY 2016 encountered by IM physicians. Formal echocardiography may not always be quickly available, nor are the cost and resources spent on a full echocardiogram always necessary to answer focused questions. Traditional physical exam techniques to assess cardiac function, intravascular volume, and fluid responsiveness lack significant sensitivity and specificity even among expert diagnosticians.22–26 The steady decline of the traditional physical exam in recent years is attributable to various causes including decaying physician exam skills, increasing patient obesity, and with the routinely available correlation to echocardiography and CT scans, an increasing realization that the traditional physical exam is inadequate.1,27–29 Thus, an immediately available and interpretable cardiac FoCUS exam, performed by the physician who can integrate the findings with other clinical information, with better test characteristics than traditional physical exam techniques improves the diagnostic ability of the IM physician. Alexander et al showed that IM residents who completed a brief, 3-hour training course in echocardiography could use FoCUS to assess LVSF with moderate accuracy (j5 0.51) when compared with formal echocardiography.14 Croft et al showed that after a 15-hour training course in echocardiography, IM residents using a hand-carried FoCUS device could significantly improve their ability to assess LVSF compared with their traditional physical exam skills alone 95 JOHNSON ET AL TABLE 2 Test Characteristics of Internal Medicine Bedside Cardiac Ultrasound Compared with Formal Cardiologist Interpreted Echocardiography Left Ventricular Systolic Function (Ejection Fraction %) Normal (50%) Mild/moderate LV dysfunction (31–49%) Severe LV dysfunction (30%) Any LV dysfunction (<50%) Exams (n 5 178) Sensitivity Specificity 111 44 22 67 0.88 (95% CI 0.81, 0.93) 0.70 (95% CI 0.51, 0.84) 0.72 (95% CI 0.50, 0.88) 0.91 (95% CI 0.80, 0.97) 0.92 (95% CI 0.80, 0.97) 0.86 (95% CI 0.79, 0.91) 0.97 (95% CI 0.92, 0.99) 0.88 (95% CI 0.81, 0.93) Abbreviation: LV, left ventricular. (18% improvement). The gold standard used by Croft et al was a trained, noncardiologist echocardiography technician.15 Decara et al showed that after a 20-hour training course in echocardiography, IM residents could identify decreased LVSF with a moderate sensitivity and high specificity when compared with experienced cardiologists.16 Lucas et al showed that after a 27-hour cardiac FoCUS training program, board-certified IM physicians could identify decreased LVSF with good sensitivity (84%) and specificity (85%) when compared with formal echocardiography.17 Our study demonstrates that after completing the IMBUS training course and a mastery learning18,19 pathway, IM physicians could identify decreased LVSF with high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent agreement (j) when compared with formal cardiologist-interpreted echocardiography. Further subcategorization at the extremes of “normal” or “severely reduced” LVSF remains highly accurate as does the ability to differentiate normal from any abnormal function. The increased difficulty in accurately characterizing LVSF with FoCUS in the “mild-moderately reduced” category is a problem commonly recognized among cardiologists as well.30 This supports the need for a required distribution of LVSF impairment categories among the experience of a physician who is considered competent in FoCUS. The gold standard of formal echocardiography used in this study has limitations in that there is inherent interobserver variability and therefore sensitivity/specificity of the comparative test can never be 100%. The observed agreement between FoCUS and formal echocardiography in this study is similar to the published literature values for cardiologist interobserver variability of LVSF. Two studies reported a j of 0.63 14,31 and another reported a q (intraclass correlation coefficient) of 0.65.32 The intraobserver variability in our echocardiography 96 laboratory has previously been published with j 5 0.78 for measurement of LVSF.33 The patient population included in the study is unique in that it was a real-life clinical inpatient population with complex diseases, multiple comorbidities contributing to difficult cardiac sonographic exams (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease 19%, obesity 34%), and a high prevalence of technically limited formal exams (20%). The rationale for not excluding these technically difficult patients from the study was to try and assess the true clinical test characteristics of IM cardiac FoCUS in the inpatient settings where the exam is often most needed and its information most valuable. The same patient and clinical characteristics that make cardiac echocardiography technically difficult also make traditional physical exam techniques difficult to assess. Thus, an especially useful role of FoCUS for IM physicians may be in the technically difficult-to-assess patient population. Despite 20% of patients having formal echocardiograms that were “technically limited due to patient factors,” echogenicity of FoCUS exams was technically adequate to at least categorize LVSF 100% of the time. There is significant work currently in the area of FoCUS to quantify the scope and training required for various providers to be “credentialed” or “proficient” in an area and application of FoCUS. Kimura et al developed and implemented a FoCUS curriculum within their IM residency program and concluded that it is feasible to teach IM residents FoCUS.34 Based on the available literature, guidelines have been published from organizations such as the American Society of Echocardiography, American College of Emergency Physicians for emergency cardiac sonographic examinations, and the Society of Critical Care Medicine.35–40 However, the recommendations for FoCUS training and certification will undoubtedly differ among various physician groups and various applications. Our IMBUS program incorporates JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ULTRASOUND INTERNIST ASSESSMENT OF SYSTOLIC FUNCTION an intensive educational and mastery learning and certification process that not only utilizes a minimum quantity of exams by the IM physician but also fully evaluates the complete use of FoCUS, including image acquisition, image interpretation, and appropriate clinical integration of findings. Such an intensive certification approach is not necessarily feasible for all programs, but adds another training methodology to the small amount of available literature on training and utility of FoCUS among IM physicians. There are some limitations to our study. We acknowledge that this study is looking only at the ability of FoCUS to evaluate the presence of LVSF impairment and is not addressing the 50% of patients hospitalized with heart failure and preserved LVSF.41 LVSF and its visual assessment are a dynamic process dependent on the current cardiac loading conditions, rhythm, and myocardial contractility. The potential time between FoCUS and formal echocardiography (median 19 hours) is one of the limitations of this study as it allows for potential changes in these variables thus affecting LVSF in the acute and dynamic inpatient environment. A patient receiving fluid resuscitation for hypovolemia may move across the LVSF spectrum from hyperdynamic to normal or reduced function. Thus, if such interventions are made between the time of the FoCUS exam and formal echocardiogram, the assessments of LVSF may not correlate. However, the lack of an inverse relationship between interrater agreement and duration of time separating FoCUS and formal echocardiography exams (exam quartiles: <3 hours, 3–19 hours, 19–24 hours, and >24 hours) would suggest that this is not a significant confounder. Given that patients included in this study were also undergoing formal echocardiography, we cannot exclude that selection bias played a role in the outcome of the study. However, since 68% of the exams had normal LVSF, this is likely not a significant confounder to the calculated sensitivity and specificity. The physicians performing the FoCUS studies, although blinded to prior and current formal echocardiography data, were not blinded to the clinical scenario at the time of the FoCUS exam. Therefore, knowledge of information, such as b-type natriuretic peptide level, medication usage (eg, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, beta-blockers, aldosterone antagonists, etc.), and prior implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator or biventricular pacemaker, may have influenced interpretation of LVSF. In practice, the clinical knowledge of VOL. 44, NO. 2, FEBRUARY 2016 a patient’s symptoms and clinical data is an important contributor to the overall interpretation of FoCUS. The results of this study would not reflect the real application of FoCUS if physicians had been blinded to this clinical knowledge when performing and interpreting the study. The physicians were not asked to give a clinical assessment of the cardiac function prior to the FoCUS exam. Thus, we were unable to compare the physician’s presonographic clinical diagnosis with the FoCUS findings. IM physicians with rigorous bedside sonographic training within a mastery learning environment can use FoCUS in technically difficult hospitalized patients to identify decreased LVSF with high sensitivity, specificity, and strong agreement with formal cardiologistinterpreted echocardiography. This study suggests that cardiac FoCUS is most accurate at the extremes of the LVSF spectrum (normal and severely reduced), or in simply differentiating normal from abnormal LVSF. REFERENCES 1. Conn RD, O’Keefe JH. Cardiac physical diagnosis in the digital age: an important but increasingly neglected skill (from stethoscopes to microchips). Am J Cardiol 2009;104:590. 2. Mangione S, Nieman LZ, Gracely E, et al. The teaching and practice of cardiac auscultation during internal medicine and cardiology training. A nationwide survey. Ann Intern Med 1993;119:47. 3. Biais M, Carrie C, Delaunay F, et al. Evaluation of a new pocket echoscopic device for focused cardiac ultrasonography in an emergency setting. Crit Care 2012;16:R82. 4. Carrie C, Biais M, Lafitte S, et al. Goal-directed ultrasound in emergency medicine: evaluation of a specific training program using an ultrasonic stethoscope. Eur J Emerg Med 2014. 5. Vieillard-Baron A, Charron C, Chergui K, et al. Bedside echocardiographic evaluation of hemodynamics in sepsis: is a qualitative evaluation sufficient? Intensive Care Med 2006;32:1547. 6. Goodkin GM, Spevack DM, Tunick PA, et al. How useful is hand-carried bedside echocardiography in critically ill patients? J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37: 2019. 7. Rugolotto M, Hu BS, Liang DH, et al. Rapid assessment of cardiac anatomy and function with a new hand-carried ultrasound device (OptiGo): a comparison with standard echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2001;2:262. 8. Torres-Macho J, Anton-Santos JM, GarciaGutierrez I, et al. Initial accuracy of bedside ultrasound performed by emergency physicians for multiple indications after a short training period. Am J Emerg Med 2012;30:1943. 97 JOHNSON ET AL 9. Testuz A, Muller H, Keller PF, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of pocket-size handheld echocardiographs used by cardiologists in the acute care setting. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14:38. 10. Bossone E, DiGiovine B, Watts S, et al. Range and prevalence of cardiac abnormalities in patients hospitalized in a medical ICU. Chest 2002;122: 1370. 11. Joseph MX, Disney PJ, Da Costa R, et al. Transthoracic echocardiography to identify or exclude cardiac cause of shock. Chest 2004;126:1592. 12. Orme RM, Oram MP, McKinstry CE. Impact of echocardiography on patient management in the intensive care unit: an audit of district general hospital practice. Br J Anaesth 2009;102:340. 13. Volpicelli G, Lamorte A, Tullio M, et al. Point-ofcare multiorgan ultrasonography for the evaluation of undifferentiated hypotension in the emergency department. Intensive Care Med 2013;39: 1290. 14. Alexander JH, Peterson ED, Chen AY, et al. Feasibility of point-of-care echocardiography by internal medicine house staff. Am Heart J 2004;147:476. 15. Croft LB, Duvall WL, Goldman ME. A pilot study of the clinical impact of hand-carried cardiac ultrasound in the medical clinic. Echocardiography 2006;23:439. 16. DeCara JM, Lang RM, Koch R, et al. The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr 2003;4:141. http://www.ncbi.nlm. nih.gov/pubmed?cmd5search&term5DeCara%20 JM%2C%20Lang%20RM%2C%20Koch%20R. 17. Lucas BP, Candotti C, Margeta B, et al. Hand-carried echocardiography by hospitalists: a randomized trial. Am J Med 2011;124:766. 18. Block JH. Mastery Learning: Theory and Practice. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston; 1971. 19. McGaghie WC, Miller GE, Sajid AW, et al. Competency-based curriculum development in medical education. Geneva: World Health Organisation; 1978. 20. Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. Boca Raton (FL): Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1999. 21. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159. 22. Brennan JM, Blair JE, Goonewardena S, et al. A comparison by medicine residents of physical examination versus hand-carried ultrasound for estimation of right atrial pressure. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:1614. 23. Kobal SL, Trento L, Baharami S, et al. Comparison of effectiveness of hand-carried ultrasound to bedside cardiovascular physical examination. Am J Cardiol 2005;96:1002. 24. Panoulas VF, Daigeler AL, Malaweera AS, et al. Pocket-size hand-held cardiac ultrasound as an adjunct to clinical examination in the hands of medical students and junior doctors. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2012;14:323. 98 25. Razi R, Estrada JR, Doll J, et al. Bedside handcarried ultrasound by internal medicine residents versus traditional clinical assessment for the identification of systolic dysfunction in patients admitted with decompensated heart failure. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2011;24:1319. 26. McGee SR. Evidence-based physical diagnosis. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders; 2012. 27. Jauhar S. The demise of the physical exam. N Engl J Med 2006;354:548. 28. Kugler J, Verghese A. The physical exam and other forms of fiction. J Gen Intern Med 2010;25:756. 29. Verghese A, Brady E, Kapur CC, et al. The bedside evaluation: ritual and reason. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:550. 30. Johri AM, Picard MH, Newell J, et al. Can a teaching intervention reduce interobserver variability in LVEF assessment: a quality control exercise in the echocardiography lab. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:821. 31. Blondheim DS, Beeri R, Feinberg MS, et al. Reliability of visual assessment of global and segmental left ventricular function: a multicenter study by the Israeli Echocardiography Research Group. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2010;23:258. 32. Palmieri V, Dahlof B, DeQuattro V, et al. Reliability of echocardiographic assessment of left ventricular structure and function: the PRESERVE study. Prospective Randomized Study Evaluating Regression of Ventricular Enlargement. J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:1625. 33. Harris KM, Schum KR, Knickelbine T, et al. Comparison of diagnostic quality of motion picture experts group-2 digital video with super VHS videotape for echocardiographic imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2003;16:880. 34. Kimura BJ, Amundson SA, Phan JN, et al. Observations during development of an internal medicine residency training program in cardiovascular limited ultrasound examination. J Hosp Med 2012;7:537. 35. Spencer KT, Kimura BJ, Korcarz CE, et al. Focused cardiac ultrasound: recommendations from the American Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2013;26:567. 36. American College of Emergency Physicians. Use of ultrasound imaging by emergency physicians [policy statement]. Ann Emerg Med 2001;38:469. 37. Mayo PH, Beaulieu Y, Doelken P, et al. American College of Chest Physicians/La Societe de Reanimation de Langue Francaise statement on competence in critical care ultrasonography. Chest 2009; 135:1050. 38. Via G, Hussain A, Wells M, et al. International evidence-based recommendations for focused cardiac ultrasound. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014;27: 683.e1. 39. Ultrasound Certification Task Force on behalf of the Society of Critical Care Medicine. Recommendations for Achieving and Maintaining Competence and Credentialing in Critical Care Ultrasound with Focused Cardiac Ultrasound and JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ULTRASOUND INTERNIST ASSESSMENT OF SYSTOLIC FUNCTION Advanced Critical Care Echocardiography. http:// journals.lww.com/ccmjournal/Documents/Critical%20 Care%20Ultrasound.pdf. Accessed on December 3, 2014. 40. American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency ultrasound guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 2009;53:550. VOL. 44, NO. 2, FEBRUARY 2016 41. Yancy CW, Lopatin M, Stevenson LW, et al. Clinical presentation, management, and in-hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol 2006;47:76. 99