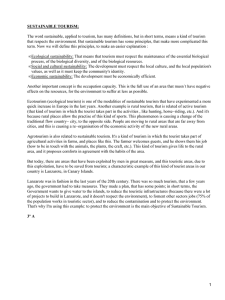

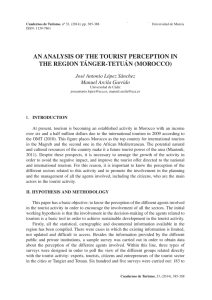

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280206550 Culture, Product Differentiation and Market Segmentation: A Structural Analysis of the Motivation and Satisfaction of Touri.... Article in Tourism Economics · June 2015 DOI: 10.5367/te.2015.0483 CITATIONS READS 35 1,269 4 authors, including: João Romão Peter Nijkamp Yasuda Women's University Tinbergen Institute Amsterdam 58 PUBLICATIONS 588 CITATIONS 1,083 PUBLICATIONS 24,603 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Eveline S. Van Leeuwen Wageningen University & Research 103 PUBLICATIONS 950 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: AG2020 View project AG2020 View project All content following this page was uploaded by João Romão on 23 November 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Tourism Economics, 2015, 21 (3), 455–474 doi: 10.5367/te.2015.0483 Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation: a structural analysis of the motivation and satisfaction of tourists in Amsterdam JOÃO ROMÃO Research Centre for Spatial and Organizational Dynamics, University of Algarve, Faro, Portugal. E-mail: [email protected]. (Corresponding author.) BART NEUTS School of Hospitality and Tourism, AUT University, Auckland, New Zealand. PETER NIJKAMP Department of Spatial Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, VU University, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. EVELINE VAN LEEUWEN Department of Spatial Economics, Faculty of Economics and Business Administration, VU University, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. The varied supply of tourism services – with particular emphasis on tangible and intangible cultural aspects – corresponds ideally to visitors’ characteristics and wishes. This paper considers a major tourist destination, such as Amsterdam, as an export-oriented multiproduct company, characterized by spatial and functional market segmentation and monopolistic competition reflected in product differentiation. Urban branding and attractiveness may favour tourist destination loyalty. The complex decision web of motivation and satisfaction of tourists in Amsterdam is analysed with a structural equations model (SEM). The authors find that different tourist profiles, in terms of personal characteristics and motivations, can significantly impact the satisfaction received from tourism services. Furthermore, and most interestingly, the results suggest that satisfaction does not necessarily lead to improved destination loyalty, but is contingent on the source of satisfaction. In this case, satisfaction resulting from tangible or intangible cultural sources has clearly different implications for loyalty, with relevant managerial implications. Keywords: market segmentation; tourist satisfaction; destination loyalty; intangible heritage; structural equations model 456 TOURISM ECONOMICS Even though travelling is an ancient phenomenon, not until the 1960s did tourism become a widespread leisure activity, increasingly motivated by pleasure and relaxation. Since that time we have seen a rapid rise in this new leisure society, with 2012 for the first time registering over one billion international tourist arrivals (United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO), 2013). Not only has travelling become more accessible to a broader public; it has also become increasingly diversified. This development prompts a new challenge to tourism destinations: can they offer a broad package of tourism facilities to meet the particular demands of specific groups of tourists? A wide spectrum of tourism services is able to attract a diversified group of potential clients and to potentially increase their loyalty, making the tourism region less vulnerable to various demand side shifts or to the seasonality of tourism. A tourism destination is not a set of distinct natural, cultural, artistic or environmental resources, but an inclusive appealing product complex that is offered in a certain appropriate place; it is based on a broadly composed and integrated portfolio of services offered by a place or destination that supplies a multidimensional holiday experience, which meets the various needs of a heterogeneous group of modern tourists. A tourism destination thus produces a composite package of tourist services based on its indigenous supply (or attraction) potential. It should be added that the attractiveness of a city as an urban tourist complex depends not only on the presence of facilities of all kinds, but also on the information provided on these facilities. Thus, tourism marketing has become a critical success factor for each destination. And therefore, web-based information (such as pre-trip information) and electronic information devices (such as portable GPS equipment) are also of great importance (Neuts et al, 2013a), with implications for the satisfaction achieved by tourists at the destination (Neuts et al, 2013b). From this perspective, tourism destinations produce a large set of products and services under the same brand, and the tourist’s overall experience is the result of the satisfaction received from multiple experiences related to these products and services (Buhalis, 2000). Consequently, tourism destinations become heterogeneous multi-product, multi-client business organizations. One may therefore regard such modern tourist complexes as export-oriented multiproduct companies, characterized by spatial and functional market segmentation, and by monopolistic competition, reflected in product differentiation (Matias et al, 2007). In a competitive environment, product differentiation is therefore of primary importance to the attraction of new tourists and provision of incentives for repeat visits. This latter aspect, loyalty to a destination, is commonly assumed to be an important aspect of destination marketing: it is less costly to attract a satisfied visitor than a new one; tourists are better informed in the repeat visits (implying that they can reach higher levels of satisfaction); and they promote the destination at no cost in a very effective way (word of mouth among their circle of friends). In fact, repeat visitors can contribute to the achievement of higher revenues and profits for tourism companies. Loyalty improvement could then be considered an effective way to increase destination competitiveness and it therefore is of primary importance to identify the product characteristics that increase tourist satisfaction and the way in which this satisfaction might translate into loyalty. Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 457 This study therefore aims to conceptualize and model the force field of modern tourism, from both the demand and supply sides. Particular attention will be paid to the motivation, satisfaction and loyalty of tourists concerning the destination of Amsterdam. Amsterdam received 5 million tourists in 2007 (when the data for this article were collected), a number that increased to 5.7 million in 2012, making Amsterdam one of the top 10 European cities for tourism. The importance of cultural assets for the attractiveness of the city is clearly expressed by the percentage of tourists who visit at least one museum: 73% in 2007 and 85% in 2011 (ATCB, 2012). This article pays special attention to the role of cultural heritage in attracting visitors and to its implications for the satisfaction and loyalty of the tourists, by presenting an innovative approach, based on a broad concept of urban cultural heritage including the built environment (museums, monuments or architecture), cultural events (concerts, festivals and other happenings) and also intangible cultural aspects (local knowledge, local values or lifestyle), with tourists being given the opportunity to express their opinion on what was to be considered cultural heritage during the empirical fieldwork. The paper is organized as follows. The second section, provides the necessary background based on a literature search for conceptualizing the structure of a tourism complex. Then, the third section discusses the database on the city of Amsterdam, while the fourth section presents the statistical methodology. The fifth and sixth sections present and interpret the results. In the seventh and final section we offer our concluding remarks. Motivation, satisfaction and loyalty in tourism As mentioned above, the tourism market is a varied and multi-client system. The heterogeneity of tourists is related to their personal characteristics; their origin, age, level of education, social conditions, cultural values or other individual attributes all influence the choice of tourism destinations and the related expectations, perceptions and motivations they bring to the destination. The identification of this market heterogeneity is assumed in the literature to be an extremely important element in defining effective marketing strategies (Kozak and Rimmington, 2000; Castro et al, 2007). In fact, the place image created by each tourist about a destination influences his or her decision to travel, the choice of a destination, the motivations to experience particular aspects of each place, the choice of products and services to be consumed during the holiday, satisfaction with the travel, and, consequently, the loyalty to a destination (Chen and Tsai, 2007). There is a general consensus in the literature about the importance of identifying push and pull motivations to define proper marketing strategies. As proposed by Crompton (1979), push factors influence the decision to travel and are related to intangible and intrinsic personal preferences of tourists (relaxation, entertainment, escape from routine, adventure, sports); pull factors (culture, heritage, museums, climate, landscape) affect the choice of a specific destination, and are related to the tangible attributes of each place (Dann, 1981; Kozak, 2002; Bansall and Eizelt, 2004; Yoon and Uysal, 2005). As the push factors are not necessarily related to the specific characteristics of the city and 458 TOURISM ECONOMICS Arch Museums Landsc Atmosph Business Culture Shopping Business Nightlife Entertainment Motivations (1) Arch Sex Income Educ Satisfaction Age Characteristics Business (3) (4) (4) Mherit Tangible (2) Monum Museums Landsc Intangible Holiday Tradition Customs Knowl National Loyalty Return Recomm Figure 1. Conceptual model of the tourist–loyalty process as function of a tourism complex. the satisfaction achieved with its different elements and services, the analysis focuses on pull factors. A first important aspect to be analysed is the relationship between the characteristics of tourists (reason to travel, nationality, age, sex, level of income, level of education or membership of a heritage club) and their pull motivations (business, shopping, nightlife, atmosphere, cultural events, museums, architecture or landscape) to visit a tourism destination (represented by arrow 1 in Figure 1). Martín Armario (2008) describes this interrelation between – before journey – personal characteristics and intended behaviour at the destination (that is, the motivation to travel) as the first phase in tourist behaviour. The second phase concerns the experience at the destination (Martín Armario, 2008). The link between the pre-journey motivations and satisfaction is identified by Lubbe (1998), who stresses that the motivation to travel is linked with the awareness of certain needs and the realization that a particular destination might serve to fulfil those needs. According to the motivations with which specific segments of the tourist market travel, different sets of products and services might be enjoyed and the satisfaction obtained could differ. This relationship could allow for a better understanding between the pull aspects of the destination that are important for specific segments and the satisfaction provided by these, leading to a better segmentation of specific tourist groups (Chi and Qu, 2008; Lee, 2009). Therefore, a second aspect to be analysed in this work is the relationship between the motivations expressed by tourists visiting a tourism destination and the levels of satisfaction they obtained with the different aspects of the city (represented by arrow 2 in Figure 1). Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 459 While satisfaction with the destination resources is thus directly related to travel motives, personal characteristics are hypothesized to have both an indirect effect via the motivational travel aspects, and a direct effect on satisfaction. As a primary hypothesis, personal characteristics are expected to influence mainly the motives that are important for visiting Amsterdam, defining different tourist segments. Next, these motives can be considered as expectations of the destination, with the tourist deciding on a specific destination because it is seen as a means to serve the motivational need (Aziz and Ariffin, 2009). If expectations regarding these motives are met, this should result in satisfaction. However, some personal characteristics might directly affect the level of satisfaction received from a tourist experience, irrelevant of the motivation for travelling. This would suggest that some market segments are more likely to be (dis)satisfied due to personality traits or other socio-demographic variables (represented by arrow 3 in Figure 1). Furthermore, assuming that the loyalty to a tourism destination is related to the satisfaction obtained on a previous visit or previous visits, as is commonly assumed in the literature, it is important to understand how the satisfaction with each aspect of the tourism supply influences the loyalty to the destination. As the overall satisfaction of a tourist results from the satisfaction obtained from each of their experiences with different services and elements of the tourism supply, all these elements contribute to the loyalty of tourists regarding a destination (Castro et al, 2007; Lee, 2009). This loyalty can be evaluated by taking into consideration the intention of the tourists to return and/or to recommend the visit to their families and friends (Oppermann, 2000; Yoon and Uysal, 2005; Chen and Tsai, 2007). Accordingly, the fourth aspect to be analysed is the relationship between the satisfaction obtained with the different aspects of the city and the loyalty to Amsterdam as a tourism destination (represented by arrow 4 in Figure 1). The analysis developed in the present study starts from the segmentation of the tourism market, considering the different characteristics of tourists in order to identify their motivations, the relationship of these personal characteristics and motivations to the level of satisfaction obtained with each aspect of the tourism supply, and the implications of the satisfaction for the loyalty to the destination. Finally, the direct relationship between the characteristics of the tourists (segmentation) and the loyalty will be analysed (represented by arrow 5 in Figure 1). The architecture of the conceptual model with the relationships to be analysed in our study is shown in Figure 1. Our statistical analysis will be performed using a structural equation model (SEM). Some recent examples of the use of SEMs are found in Chen and Chen (2010), Chen and Tsai (2008), Lee et al (2007) Lee and Hsu (2013) Yoon and Uysal (2005), all of them analysing the relationship between motivations and loyalty. Castro et al (2007), Chen and Tsai (2007), Chi and Qu (2008) and Lee (2009) include the concept of ‘image’ of a destination to analyse the loyalty of tourists. Dyer et al (2007) model the residents’ perceptions related to tourism development, Abrate et al (2011) use a SEM to analyse the relations between characteristics of places and hotels, reputation, quality and prices, while Kim and Li (2009) investigate the relation between customer satisfaction and loyalty, taking into consideration the transaction costs over the Internet. 460 TOURISM ECONOMICS Table 1. Characteristics of the variables used. Gender (female) Heritage membership (Yes) Main travel purpose Holiday Business Other Age < 18 18–34 35–54 55–74 > 74 Income < €15,000 €15,000–25,000 €25,000–35,000 €35,000–45,000 €45,000–55,000 > €55,000 Education Pre high school High school Vocational Bachelor’s degree Master’s degree Nationality Dutch Other European Other Motivations Architecture Museums Landscape Cultural events Shopping Business Nightlife Atmosphere Appreciation Architecture Monuments Museums Urban landscape Cultural events Traditions Customs Knowledge Measurement level Full sample (n = 645), frequency/mean (sd) Missing deleted (n = 523) frequency/mean (sd) Categorical Categorical Binary (Yes/No) 52.1% 20.5% 51.4% 22.4% 67.0% 10.5% 22.5% 73.4% 10.7% 15.9% 6.4% 62.8% 22.2% 8.4% 0.3% 5.2% 65.6% 21.8% 7.1% 0.4% 32.7% 18.2% 13.8% 9.5% 5.6% 20.3% 32.9% 18.2% 14.0% 9.6% 5.7% 19.7% 5.3% 22.0% 11.9% 35.0% 25.7% 4.0% 22.0% 11.5% 35.9% 26.6% 20.2% 49.6% 30.2% 19.7% 50.3% 30.0% 48.2% 65.1% 33.2% 21.6% 37.2% 6.5% 39.4% 54.0% 48.9% 63.9% 33.5% 22.0% 37.3% 6.9% 40.2% 55.4% 4.10 (0.922) 3.69 (1.023) 4.03 (0.987) 3.76 (0.967) 3.54 (1.148) 3.83 (1.086) 3.43 (1.162) 3.35 (1.100) 4.09 (0.942) 3.65 (1.047) 4.04 (0.990) 3.78 (0.976) 3.55 (1.151) 3.84 (1.068) 3.44 (1.152) 3.34 (1.112) Ordinal Ordinal Ordinal Categorical Binary (Yes/No) Ordinal Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 461 Methodology: a structural equation model The conversion of the conceptual model in Figure 1 into an operation measurement model calls for an extensive database. From the multi-purpose survey questionnaire (1), we concentrated on four aspects specifically: motives for a visit; loyalty to the destination; appreciation of the cultural heritage present; and personal characteristics of the visitors. Table 1 provides an overview of the variables concerned. The hypothesized relationships between the exogenous and endogenous variables of the model were tested with the AMOS 19 SEM package for SPSS. In an initial phase, the data were investigated for missing values. Since a number of SEM functionalities require a complete data set, it is advisable to either delete or impute cases which contain missing values. Of the 645 cases, a total of 122 cases contained at least one missing value, primarily on the income variable (n = 107). A missing-data pattern analysis did not reveal any significant association with the scores on the related variables, which indicates that a simple deletion of cases with missing values would not result in serious estimation errors. Since data-imputation would always imply the artificial construction of variable scores, and since the number of missing values to estimate is comparatively large, our further SEM analysis has only taken complete cases into account. To test our hypothesized model as shown in Figure 1, Mulaik and Millsap’s (2000) four-step modelling approach was used, consisting of: (a) (b) (c) (d) explanatory factor analysis to establish the number of latent variables; confirmatory factor analysis to confirm the measurement model; a structural model to test the relationships between the model variables; nested models testing in order to identify the most parsimonious model. While Steps (b) to (d) are intrinsic to SEM, the first step is performed in commonly used statistical software packages. The unidimensionality of each proposed construct, a necessity in the model building step, was assessed by principal component analysis (PCA) in SPSS 17.0 (Sethi and King, 1994). Since the variables used in the analysis were on either ordinal or dichotomous levels, a polychoric and tetrachoric correlation matrix was used instead of the more common Pearson’s product-moment correlation (Jöreskog and Sörbom, 1996). Table 2 gives an overview of the PCA results. Explanatory factor analysis on motivations appears to lead to a three-factor solution, based on the Kaiser criterion (eigenvalues above 1), with a cumulative explained variance of 65%. The results are in line with previous theoretical analysis (Manzanek, 2010), dividing the motivational factor into a cultural, a business and an entertainment motive. The first identified factor, (1) the cultural motivation, incorporates the visiting purposes of architecture, museums, urban landscape, cultural events and the general atmosphere of the city. The second, (2) entertainment, is largely constructed from the items shopping and nightlife. The third, (3) business, is mainly concerned with one variable: visits that have business as a driving factor. The PCA applied to the satisfaction variables yields a two-factor solution with a cumulative explained variance of 62%. Table 2 gives an overview of the construction of the two satisfaction factors. Factor 1 combines all variables 462 TOURISM ECONOMICS Table 2. Varimax rotated component matrix of motivation and satisfaction. Items Factors 1 2 3 Motivations Activities planned architecture Activities planned museums Activities planned landscape Activities planned cultural events Activities planned shopping Activities planned business Activities planned nightlife Activities planned atmosphere 0.790 0.660 0.789 0.403 –0.026 –0.030 0.282 0.686 0.094 0.284 –0.082 0.272 0.895 0.063 0.652 0.260 0.081 –0.403 0.063 0.560 –0.003 0.839 0.252 0.215 Satisfaction Appreciation of architecture Appreciation of monuments Appreciation of museums Appreciation of urban landscape Appreciation of cultural events Appreciation of traditions Appreciation of customs Appreciation of knowledge 0.138 0.160 0.065 0.158 0.455 0.891 0.886 0.850 0.824 0.767 0.727 0.687 0.226 0.068 0.122 0.123 concerning the satisfaction with intangible heritage: traditions, customs and knowledge, while the second component, Factor 2, depends mainly on satisfaction with the tangible heritage, namely, the city’s architecture, monuments, museums and urban landscape. This distinction between the role of tangible and intangible cultural aspects of the city is the major theoretical contribution of this work, leading to important practical and managerial consequences. After conducting this exploratory factor analysis, a confirmatory factor analysis – to test the adequacy and validity of individual items and latent variables – and SEM – to test the significance of the hypothesized paths between all variables – was performed in AMOS. Both maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation were used. A Bayesian approach is normally advocated in case of ordinal or dichotomous measurement levels and a non-normal distribution, both observed in the data. However, it should be noted that various authors have observed only marginal differences between maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation outcomes (Byrne, 2010). Therefore, the decision was taken to run a simultaneous maximum likelihood estimation in order to compare the results and model fit indices. Results The model fit indices for the original confirmatory factor measurement model indicate a model misspecification with a chi-square (χ²) statistic of 664.745 (df = 229, p-value = 0.000), a normal chi-square (χ²/df) of 2.903, a root mean Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 463 square error of approximation (RMSEA) of 0.060 and a comparative fit index (CFI) of 0.890 (for a discussion of thresholds, see Wheaton et al, 1977; Steiger, 2007 and Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007). Apart from looking at the total model fit indices, the significance of the individual factor loadings should also be considered (Hooper et al, 2008). None of the measurement items had nonsignificant factor loadings at a 99% confidence interval, while the mean values and standard errors of the items (as seen in the appendix) show, on average sufficient scores to use in a SEM. Indeed, all but two standardized regression weights were above the minimal level of 0.30 (Merenda, 1997; Hair et al, 1998). Only the item indicating a shopping motivation (0.270) and the item measuring satisfaction through cultural events (0.295) were below this threshold value. The Bayesian estimation procedure shows largely comparable parameter estimates. The measurement model was improved by correlating measurement errors between a number of motivational and satisfaction items, since it could be presumed that the response on travel motive and satisfaction is influenced by the same underlying structures. Furthermore, both the ‘appreciation of cultural events’ and the ‘motivation for cultural events’ were deleted from their latent constructs, since the standardized regression weights were below or only marginally above the 0.30 level. The shopping motive was kept in the analysis for its theoretical value. Apart from a χ²-value of 337.607 (df = 177, p-value = 0.000) – which is known to be sensitive to sample size, departures from multivariate normality and model complexity (Schumacker and Lomax, 2004) – all other model fit indices now show an acceptable value (χ²/df = 1.907, RMSEA = 0.042, CFI = 0.956). Furthermore, analysis of both convergent – the extent of internal factor consistency – and discriminant – the extent of distinctness between factors – validity supported the model structure. Convergent validity can most easily be tested in confirmatory factor analysis by inspecting the significance of factor loadings of each measurement item (Bagozzi et al, 1991; Hill and Hughes, 2007). All factor item scores of our final measurement model were found significant on a 99% confidence level, while only the standardized score of shopping stayed below the 0.30 threshold, as can be observed from Table 3. Discriminant validity was tested by assessing whether the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) of each latent construct was larger than the correlation between different latent constructs. Furthermore, the AVE for each construct should at least be as high as 0.50 (Zait and Bertea, 2011). Table 4 gives an overview of the AVE – on the diagonal – as compared to the interfactor correlations. Since all squared AVE-values are much larger than the correlations between different factors and the non-squared values are above 0.50, we can assume that the latent factors are sufficiently dissimilar. In a next step, causal relationships were added according to the theoretical model of Figure 1 and tested on path significance. The results of the initial Maximum Likelihood estimation procedure revealed acceptable model-fit indices (χ²/df = 2.166, RMSEA = 0.047, CFI = 0.941), even though the χ²-value = 400.699 (df = 185, p-value = 0.000) was significant. However, only a limited number of regression paths were found to have significant estimates at a 95% confidence level. Comparable results were found with the use of Bayesian estimation. To test the impact of these non-significant relationships, 464 TOURISM ECONOMICS Table 3. (Un)standardized factor weights of measurement items. Factor Item Unstandardized estimates (SE) Standardized estimate Motive Culture Architecture Museums Landscape Atmosphere 1.000 0.986 (0.102)*** 0.779 (0.094)*** 0.813 (0.101)*** 0.574 0.584 0.469 0.467 Motive Shop Shopping Nightlife 1.000 3.424 (1.074)*** 0.271 0.915 Satisfaction Tangible Architecture Monuments Museums Urban Landscape 1.000 0.996 (0.088)*** 0.760 (0.075)*** 0.766 (0.075)*** 0.737 0.656 0.529 0.543 Satisfaction Intangible Traditions Customs Knowledge 1.000 1.173 (0.066)*** 0.972 (0.060)*** 0.785 0.854 0.733 Loyalty Recommend Return 1.000 0.921 (0.033)*** 0.963 0.841 Note: * p-value < 0.05; ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001. Table 4. Average variance extracted analysis. Motive culture Motive shop Satisfaction tangible Satisfaction intangible Loyalty Motive culture Motive shop Satisfaction tangible Satisfaction intangible 0.903 0.347 0.205 0.372 0.637 0.990 –0.063 0.266 0.303 0.754 0.318 –0.065 0.841 0.344 Loyalty 0.985 paths were deleted one by one, based on their significance levels and the value of the standardized regression estimates (with the lowest values deleted first). A likelihood ratio test could then be performed on each step to investigate whether the relationship could be erased from the model on grounds of parsimony without significantly affecting the model fit. In Table 5 we compare the difference between the χ²-value of the less parsimonious model with the χ²-value of the nested model with that between the tabled χ²-values for the related degrees of freedom. While in general a lower value is preferred, for an insignificant difference the modification should be accepted on grounds of parsimony. Since the tabled χ²-value for one degree of freedom (that is, one extra path deleted) and an α-level of 0.05 is 3.48, we can conclude that only the final step in Table 5 shows a significant difference in χ²-value, thus giving preference to the more constricted model on grounds of Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation δ1 δ2 δ3 δ4 δ5 δ6 δ7 Arch Museums Landsc Atmosph Business Shopping Nightlife M1 ε1 ε2 M2 M3 Holiday 465 ε3 ε4 Business Arch δ8 Monum δ9 S1 Age Museums δ10 Sex Landsc δ11 Income ε5 Educ S2 Mherit Dutch L Return δ15 Tradition δ12 Customs δ13 Knowl δ14 ε6 Recomm δ16 Figure 2. Operational structural equation model. Notes: For reasons of readability, covariances are not shown in the model. Only significant paths are shown. M1 = culture motive; M2 = business motive; M3 = entertainment motive; S1 = satisfaction tangible; S2 = satisfaction intangible; L = loyalty, χ² (204) = 390.872, p = 0.000, χ²/df (1.916), RMSEA = 0.043, CFI = 0.942. parsimony in all other 36 cases. Furthermore, the variable ‘other European’ could be deleted altogether since all regression weights were set to zero, further facilitating the model. In the final structural model, 27 regressions were included in the model, 26 of which were significant on an α-level of 0.05 or lower – only the t-test of the relationship between business and loyalty had a p-value slightly above 0.05 (p = 0.056). The overall model fit statistics indicate that the accepted model fits the data better than the original model. While we have to acknowledge that the χ²-value of our final model remained significant, it is a known problem that these indices are biased with small sample sizes, a large number of variables, and a non-normal data distribution (Kenny and McCoach, 2003; Schumacker and Lomax, 2004; Fan et al, 2011). Since the better performing goodness of fit indices (root mean square error of approximation, χ²/df, and comparative fit index) indicate a reasonable to good model fit for the final model, the final parameter estimates can be considered as sufficiently stable. Table 6 gives an overview of the significant unstandardized regression weight estimates with both maximum likelihood method (left side of Table 6) and Bayesian estimation (right side of Table 6). Note that since Bayesian estimates are based on a 95% confidence interval around the mean, the level of significance for these estimates is maximized at an α-level of 0.05. Both estimates under maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation generate comparable results, with consistent unstandardized factor weights and significance. However, as indicated 466 TOURISM ECONOMICS Table 5. Likelihood ratio analysis of nested models. Steps Path deleted 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 Full model Other European → L Other European → M2 Holiday → L Holiday → M2 Other European → M3 Education → M1 Other European → M1 Age → M2 Business → S1 Heritage membership → S2 Gender → M1 Heritage membership → M2 Holiday → S2 Education → M2 Heritage membership → M3 Income → M1 Business → S2 Gender → M2 Age → M1 M2 → S1 Income → M3 Income → S2 Age → S2 Heritage membership → S1 Education → S2 Business → M1 Other European → S2 M3 → S1 Business → M3 Other European → S1 Dutch → S2 Gender → L Income → S1 Age → L Dutch → M2 Business → L df ⎟² D² 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221 400.699 400.699 400.701 400.707 400.716 406.707 406.826 406.966 407.038 409.150 409.206 409.276 409.370 409.474 409.674 409.842 410.064 410.387 410.796 411.255 411.747 412.544 413.434 413.898 414.695 415.547 416.413 417.452 418.616 419.859 421.133 422.126 424.032 426.245 428.570 431.089 434.709 0.000 0.002 0.006 0.009 5.991 0.119 0.140 0.072 2.112 0.056 0.070 0.094 0.104 0.200 0.168 0.222 0.323 0.409 0.459 0.492 0.797 0.890 0.464 0.797 0.852 0.866 1.039 1.164 1.243 1.274 0.993 1.906 2.213 2.325 2.519 3.620 Note: M1 = culture motive; M2 = business motive; M3 = entertainment motive; S1 = satisfaction tangible; S2 = satisfaction intangible; L = loyalty. by other authors (Nevitt and Hancock, 2001; Mîndrilã, 2010), the standard errors of the maximum likelihood estimates are inflated under violations of multivariate normality and inadequate measurement level. As it could be expected, results from the econometric analysis confirm that a holiday purpose for travelling has a significant positive influence on both the cultural and entertainment motive, while, conversely, the business purpose has a significant positive correlation with the business motive. Another factor Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 467 Table 6. Unstandardized path estimates with maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimation. Maximum likelihood, unstandardized estimates (SE) Motive Culture Nature holiday Heritage membership Dutch nationality Bayesian estimation, unstandardized estimates (SE) 0.139 (0.031)*** 0.064 (0.030)* –0.472 (0.045)*** 0.137 (0.001)* 0.064 (0.001)* –0.467 (0.001)* 0.295 (0.033)*** 0.017 (0.005)** 0.295 (0.001)* 0.017 (0.000)* Motive Entertainment Nature holiday Age Sex Educational level Dutch nationality 0.027 (0.012)* –0.036 (0.010)*** –0.041 (0.012)*** –0.009 (0.004)* –0.042 (0.015)** 0.030 (0.000)* –0.041 (0.000)* –0.047 (0.000)* –0.010 (0.000)* –0.047 (0.000)* Satisfaction tangible Nature holiday Age Sex Education level Dutch nationality Motive culture –0.351 (0.093)*** 0.129 (0.051)* 0.137 (0.067)* 0.119 (0.028)*** 0.579 (0.176)*** 1.578 (0.331)*** –0.354 (0.002)* 0.129 (0.001)* 0.137 (0.001)* 0.118 (0.000)* 0.582 (0.005)* 1.607 (0.010)* Satisfaction intangible Sex Motive culture Motive business Motive entertainment 0.210 (0.074)** 1.257 (0.185)*** 0.314 (0.144)* 1.135 (0.372)** 0.212 (0.002)* 1.274 (0.005)* 0.312 (0.003)* 1.050 (0.011)* Loyalty Satisfaction tangible Satisfaction intangible Nature business Income Education level Heritage membership Dutch nationality –0.051 (0.016)** 0.043 (0.013)** –0.060 (0.031) –0.018 (0.005)*** 0.016 (0.008)* –0.052 (0.023)* –0.688 (0.026)*** –0.051 (0.000)* 0.043 (0.000)* –0.060 (0.001) –0.018 (0.000)* 0.016 (0.000)* –0.052 (0.001)* –0.689 (0.001)* Motive Business Nature business Income Note: * p-value < 0.05, ** p-value < 0.01, *** p-value < 0.001. positively influencing the business travel motivation is the income variable with higher-income categories more likely to visit Amsterdam for business purposes. This is also an expected result but, interestingly, the results also indicate that tourists in higher age categories seem less motivated by the entertainment opportunities in Amsterdam. This might be caused mainly by the presence of ‘shopping’ in this factor, which requires a certain income. Both the educational level and sex of the respondent have a significant negative effect on entertainment 468 TOURISM ECONOMICS as a travel motive, implying that men and higher educated tourists are less likely to travel to the destination for shopping and nightlife than women and lower-educated visitors. Furthermore, the entertainment motive seems less significant for Dutch tourists than for non-Dutch visitors. Finally, heritage membership has a significant positive influence on the cultural motive and this motivation is less important for Dutch nationals as compared with other nationalities, as it could be expected. Four of the six possible paths between motivations and satisfaction with the urban resources were found significant on an α = 0.05 level. The statistical analysis indicates the existence of a highly positive relationship between the cultural motive and the satisfaction with both tangible and intangible heritage in Amsterdam. Business travellers and tourists with an entertainment motive also appear to record comparatively higher satisfaction with intangible heritage: the traditions, customs and local knowledge at the destination. The positive relationship between sex and both tangible and intangible satisfaction is indicative of the fact that men seem to be more satisfied with Amsterdam’s tangible and intangible heritage. Other personal characteristics that further advance satisfaction with tangible city elements are age, education level and Dutch nationality. These factors all increase the chance of tourists being satisfied with the built environment. Finally, tourists travelling primarily with a holiday motive are generally less satisfied with tangible aspects. These results show the importance of the distinction between tangible and intangible heritage, since different variables can have diverse impacts on both types of tourist satisfaction. Next, from Table 6 we can deduce that both latent satisfaction variables can be significantly related to loyalty. However, while a higher satisfaction with intangible heritage leads to a higher loyalty (as it was expected), satisfaction with the tangible heritage on the destination appears to have a negative impact (which is an important and innovative result of this study). These different impacts of satisfaction with tangible and intangible cultural assets on the loyalty of tourists form a second major result that arises from the distinction between different cultural aspects of the city. Furthermore, four relationships between loyalty and personal characteristics had significant regression weights. Income has a negative weight, indicating that higher income categories show less loyalty in our dataset. Other negative relationships are found for heritage membership and Dutch nationality, while education has a significant positive value. A final point of interest is the possible indirect effects between the different travel motives and loyalty. While we did not hypothesize a direct relationship between these variables, significant indirect effects can still be estimated due to the paths connecting motives, significance and loyalty. The results of this analysis indicate a positive indirect relation between the entertainment (0.049) and business (0.013) motive with loyalty, while cultural travel motives (–0.026) have a negative indirect effect. Discussion A number of significant relationships found are intuitively meaningful and show the hypothesized signs. As expected, visitors coming to Amsterdam for Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 469 business purposes are motivated more by business opportunities in Amsterdam, while holiday purposes can be related positively to the entertainment and cultural motives. Another interesting aspect of the business motive is its correlation with a comparatively higher income, empirically validating the (expected) higher spending power of business travellers and making these visitors an interesting marketing group to target. Furthermore, travellers with a primarily business motive reported higher satisfaction with intangible heritage, indirectly leading to a significant positive effect on the return and recommendation potential of this tourist group. The fact that business travellers show higher rates of satisfaction for intangible heritage might be related to both their location in the city – with business districts often located outside of historic centres – and the time of day when they have leisure time. This group might therefore have a higher chance of experiencing intangible heritage than physical, tangible relicts. Furthermore, their business trip could trigger a future leisure return visit if the city is found enjoyable, therefore potentially increasing loyalty. While, as already mentioned, the cultural motive was related positively to the holiday travel purpose, this travel motive was furthermore of primary importance for international tourists and members of a heritage organization. Both results are expected and acknowledge the image of Amsterdam as an international cultural destination. Nevertheless, tourists visiting the city with a holiday motive achieve less satisfaction with tangible elements, which reveals the importance of the intangible aspects of local culture on the satisfaction of visitors on holidays in Amsterdam. The cultural aspects seem of less importance to Dutch visitors, who are more likely to travel for alternative purposes (such as visiting friends or relatives or for administrative reasons). Additionally, these national tourists reported less interest in shopping and nightlife as their main travel reason. This travel motive could further be related to younger people, females and people with a lower education, thereby possibly uncovering another aspect of the Amsterdam image – the libertarian atmosphere related to its drugs and prostitution laws – while also showing the importance of its shopping districts to a certain segment of travellers. While business travellers were, in general, more satisfied with the intangible aspects of Amsterdam, culturally motivated tourists indicated a higher satisfaction on both the intangible and the built environment: the architecture, museums, monuments and urban landscape. This result is sensible, since this subgroup of visitors attaches primary importance to these aspects of the city. The estimated positive relationship seems to imply that Amsterdam lives up to the expectations of cultural tourists. At the same time, shopping and nightlife tourists seemed to experience low levels of satisfaction with the tangible elements, possibly as a result of a lack of interest in these destination aspects. Furthermore, it might be argued that the historical character of the inner city, with its generally smaller streets, affects the shopping experience since the main shopping street in the centre of Amsterdam: Kalverstraat, is sensitive to crowding issues. An important and perhaps counterintuitive empirical observation relates to the association between satisfaction and tourist loyalty. Specifically, tourists who achieve higher levels of satisfaction with intangible aspects of the city tend to be more loyal while the opposite holds true in case of satisfaction with tangible 470 TOURISM ECONOMICS heritage. An explanation might be that tourists who mainly experience satisfaction with the built environment have a more shallow relationship with the destination. This segment of cultural visitors might then comprise of ‘collectors’ of cultural experiences; travellers who visit a destination once to be able to check it from the list and then move on to another cultural attraction. As a result, these visitors, limiting themselves to visiting city areas, museums and landmark attractions, could be considered less loyal towards the destination, explicitly considering the return potential. Conversely, travellers who are both motivated by and satisfied with intangible cultural elements might have a greater potential for return visits since an intangible experience of the local culture could be more difficult to achieve in a single visit. Furthermore, intangible aspects have a deeper effect, relating to lifestyles instead of aesthetics. Both relationships seem further acknowledged by the significant indirect relationships between motivations and loyalty, where estimating the indirect effects led to the detection of a significant positive relationship between the entertainment and the business motive, while cultural travellers were found to be less loyal towards the specific destination. Finally, a number of personal tourist characteristics were found to be directly related to loyalty to Amsterdam. The lower loyalty of heritage conservation organization members confirms our results concerning the cultural motive. A significantly positive effect on loyalty was found for tourists in the lower income categories, who might be more limited in their travel possibilities, tourists with a higher level of education and non-European tourists. Conclusion The primary goal of this study was to assess the impact of several factors on the loyalty (measured by the possibility of a return visit or a recommendation to visit) to the destination of Amsterdam, since this loyalty can offer a competitive advantage to the destination in attracting future tourists. The most interesting conclusion to note, concerning the effect of different factors on visitor loyalty is the observation that higher satisfaction does not necessarily increase tourist retention. The distinction between the role of tangible and intangible cultural assets – and its implications on the satisfaction and loyalty observed for different groups of tourists – is the most interesting theoretical and practical contribution of this analysis. In fact, it was observed that intangible sources (such as traditions and customs) have a positive effect on the chance for a positive recommendation or a return visit; however, it is noteworthy that a high satisfaction with tangible resources (such as museums, architecture and urban landscape) had the opposite effect. While this seems to conflict with theoretical expectations and the popular belief, it might be explained by the fact that the group of tourists looking for these specific experiences is primarily focused on once in a lifetime experiences and will move on to other destinations once these needs are met. This has some relevant implications for tourist marketing strategies in Amsterdam, revealing that the preservation of the local life style and traditions plays an extremely important role regarding the satisfaction and loyalty of Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 471 tourists. Thus, it is important to take into consideration that the construction of attractions oriented for tourists can have negative consequences on the daily life of the local community, also with undesirable results regarding the satisfaction of tourists with these intangible elements of the city. Nonetheless, the city has shifted its attention to the higher spending market of cultural tourists, in place of backpackers and party tourism. However, such a strategy might have unfavourable effects in the longer run, since the latter groups are more likely to return in the future (possibly as cultural tourists at a later stage in their lives) while the former group, seeking a purely cultural experience, is less loyal towards the city. It might thus be advisable not to limit marketing efforts to a single segment of the tourist market and also to focus on the lifetime value of a tourist – especially considering the fact that higher income groups are also less likely to return. While the results show an interesting, somewhat unexpected relationship between satisfaction and loyalty, studies in other destinations are needed to validate the results in a larger context. The city of Amsterdam is a very particular tourist destination, with part of its international attraction due to its liberal image concerning gay rights, squatting, prostitution and soft drugs. As a result, the importance of the intangible heritage on tourist loyalty may be quite specific to the nature of the destination and the results may not be easily reproducible in other situations. Since the European framework that provided the database collected data in a number of destinations, this opens up possibilities to attempt to fit a similar model in other cities. Endnotes 1. The data used for the empirical part of this paper were mostly collected within the Sixth Framework Programme from European Union (FP6 EU) project, ‘Integrated e-Services for Advanced Access to Heritage in Cultural Tourist Destinations’ (ISAAC). The data were collected by user surveys carried out in the city of Amsterdam between August and November 2007 as part of a broader multi-purpose tourist investigation. These surveys involved extensive field data collection by interview teams hired and trained by the University of Nottingham, one of the ISAAC partners. Three different groups of people were targeted: residents, visitors (tourists) and service providers in the tourist sector. The questionnaires used both online and face-to-face interview mode (stand-alone computer versions or paper versions). In total, 31% of responses were made online, using the ISAAC website survey; 24% were done on a computer version using a laptop; and 45% were done on paper (see also ISAAC D1.4, 2007). The fieldwork developed by VU Amsterdam was exclusively focused on tourists visiting Amsterdam, where approximately 650 tourists filled out a questionnaire. References Abrate, G., Caproello, A., and Fraquelli, G. (2011), ‘When quality signals talk: evidence from the Turin hotel industry’, Tourism Management, Vol 32, pp 912–921. ATCB (2012), Amsterdam Visitor Survey, Amsterdam Tourism and Convention Bureau, Amsterdam. Aziz, N.A., and Ariffin, A.A. (2009), ‘Identifying the relationship between travel motivation and lifestyles among Malaysian pleasure tourists and its marketing implications’, International Journal of Marketing Studies, Vol 1, No 2, pp 96–106. Bagozzi, R.P., Yi, Y., and Phillips, L.W. (1991), ‘Assessing construct validity in organizational research’, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol 36, No 3, pp 421–458. Bansal, H.S., and Eiselt, H. (2004), ‘Exploratory research of tourist motivations and planning’, Tourism Management, Vol 25, pp 387–396. Buhalis, D. (2000), ‘Marketing the competitive destination of the future’, Tourism Management, Vol 21, pp 97–116. 472 TOURISM ECONOMICS Byrne, B.M. (2010), Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd edn, Routledge, New York, NY. Castro, C., Armario, E., and Ruiz, D. (2007), ‘The influence of market heterogeneity on the relationship between a destination’s image and tourists’ future behavior’, Tourism Management, Vol 28, pp 175–187. Chen, C., and Chen, F. (2010), ‘Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists’, Tourism Management, Vol 31, pp 29–35. Chen, C., and Tsai, D. (2007), ‘How destination image and evaluative factors affect behavioral intentions?’, Tourism Management, Vol 28, pp 1115–1122. Chen, C., and Tsai, D. (2008), ‘Perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty of TV travel product shopping: involvement as a moderator’, Tourism Management, Vol 29, pp 1166–1171. Chi, C., and Qu, H. (2008), ‘Examining the structural relationships of destination image, tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty: an integrated approach’, Tourism Management, Vol 29, pp 624– 636. Crompton, J. (1979), ‘Motivations for pleasure vacations’, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol VI, No 4, pp 408–424. Dann, G. (1981), ‘Tourist motivation: an appraisal’, Annals of Tourism Research, Vol VIII, No 2, pp 187–219. Dyer, P., Gursoy, D., Sharma, B., and Carter, J. (2007), ‘Structural modeling of resident perceptions of tourism and associated development on the Sunshine Coast, Australia’, Tourism Management, Vol 28, pp 409–422. Fan, X., Thompson, B., and Wang, L. (2011), ‘Effects of sample size, estimation methods, and model specification on structural equation modeling fit indexes’, Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol 6, No 1, pp 56–83. Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., and Black, W.C. (1998), Multivariate Data Analysis, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ. Hill, C.R., and Hughes, J.N. (2007), ‘An examination of the convergent and discriminant validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire’, School Psychology Quarterly, Vol 22, No 3, pp 1–23. Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., and Mullen, M.R. (2008), ‘Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit’, Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, Vol 6, No 1, pp 53–60. ISAAC D1.4 (2007), ‘Report on users requirements for ISAAC e-services using conjoint analysis’, ISAAC deliverable 1.4, (http://www.isaac-project.eu/publications.asp). Jöreskog, K.G., and Sörbom, D. (1996), LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide, Scientific Software, Chicago, IL. Kenny, D.A., and McCoach, B.D. (2003), ‘Effect of the number of variables on measures of fit in structural equation modeling’, Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol 10, No 3, pp 333–351. Kim, Y.G., and; Li, G. (2009), ‘Customer satisfaction with and loyalty towards online travel products: a transaction cost economics perspective’, Tourism Economics, Vol 15, No 4, pp 825– 846. Kozak, M. (2002), ‘Comparative analysis of tourist motivations by nationality and destinations’, Tourism Management, Vol 23, pp 221–232. Kozak, M., and Rimmington, M. (2000), ‘Tourist satisfaction with Mallorca, Spain, as an off-season holiday destination’, Journal of Travel Research, Vol 38, pp 260–269. Lee, C., Yoon, Y., and Lee, S. (2007), ‘Investigating the relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and recommendations: the case of the Korean DMZ’, Tourism Management, Vol 28, pp 204–214. Lee, T. (2009), ‘A structural model to examine how destination image, attitude, and motivation affect the future behavior of tourists’, Leisure Sciences, Vol 31, pp 215–236. Lee, T., and Hsu, F. (2013), ‘Examining how attending motivation and satisfaction affects the loyalty for attendees at aboriginal festivals’, International Journal of Tourism Research, Vol 15, No 1, pp 18–34. Lubbe, B. (1998), ‘Primary image as a dimension of destination image: an empirical assessment’, Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, Vol 7, No 4, pp 21–43. Manzanek, J. (2010) ‘Managing the heterogeneity of city tourists’, in Manzanek, J., and Wöber, K., eds, Analysing International City Tourism, 2nd edn, Springler-Verlag, Vienna. Martín Armario, E. (2008), ‘Tourist satisfaction: an analysis of its antecedents’, Asociación Española de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, Vol 17, pp 367–382. Culture, product differentiation and market segmentation 473 Matias, A., Nijkamp, P., and Neto, P. (2007), Advances in Modern Tourism Research, Springer-Verlag, New York, NY. Merenda, P.F. (1997), ‘A guide to the proper use of factor analysis in the conduct and reporting of research: pitfalls to avoid’, Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, Vol 30, pp 156–164. Mîndrilã, D. (2010), ‘Maximum likelihood (ML) and diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimation procedures: a comparison of estimation bias with ordinal and multivariate non-normal data’, International Journal of Digital Society, Vol 1, No 1, pp 60–66. Mulaik, S.A., and Millsap, R.E. (2000), ‘Doing the four-step right’, Structural Equation Modeling, Vol 7, pp 36–73. Neuts, B., Romão, J., Nijkamp, P., and van Leeuwen, E. (2013a), ‘Digital destinations in the tourist sector: a path model for the impact of e-services on tourist expenditures in Amsterdam’, Letters in Spatial and Resource Analysis, Vol 6, No 2, pp 71–80. Neuts, B., Romão, J., Nijkamp, P., and van Leeuwen, E. (2013b), ‘Describing the relationships between tourist satisfaction and destination loyalty in a segmented and digitalized market’, Tourism Economics, Vol 19, No 5, pp 987–1004 Nevitt, J., and Hancock, G.R. (2001), ‘Performance of bootstrapping approaches to model test statistics and parameter standard error estimation in structural equation modeling’, Structural Equation Modeling: a Multidisciplinary Journal, Vol 8, No 3, pp 353–377. Oppermann, M. (2000). ‘Tourism destination loyalty’, Journal of Travel Research, Vol 39, pp 78–84. Schumacker, R.E., and Lomax, R.G. (2004), A Beginner’s Guide To Structural Equation Modelling, Second Edition, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ. Sethi, V., and King, W.R. (1994), ‘Development of measures to assess the extent to which an information technology application provides competitive advantage’, Management Science, Vol 40, No 12, pp 1601–1626. Steiger, J.H. (2007), ‘Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling’, Personality and Individual Differences, Vol 42, No 5, pp 893–898. Tabachnick, B.G., and Fidell, L.S. (2007), Using Multivariate Statistics, 5th edn, Allyn and Bacon, New York, NY. United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) (2013), ‘International tourism to continue robust growth in 2013’, press release 13006, Madrid. Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D.F., and Summers, G. (1977), ‘Assessing reliability and stability in panel models’, Sociological Methodology, Vol 8, No 1, pp 84–136. Yoon, Y., and Uysal, M. (2005), ‘An examination of the effects of motivation and satisfaction on destination loyalty: a structural model’, Tourism Management, Vol 26, pp 45–56. Zait, A., and Bertea, P.E. (2011), Methods for testing discriminant validity’, Management & Marketing, Vol 11, No 2, pp 217–224. 474 TOURISM ECONOMICS Appendix Statistical Test Results Table A1. Mean scores and standard errors of latent variable items. Mean Architecture Museums Landscape Cultural events Atmosphere Shopping Nightlife Architecture Monuments Museums Urban_landscape Cultural_events Traditions Customs Knowledge Recommend Return ← M1 ← M1 ← M1 ← M1 ← M1 ← M3 ← M3 ← S1 ←S1 ←S1 ←S1 ←S2 ←S2 ←S2 ←S2 ←L ←L 1.000 0.872 0.696 0.409 0.768 1.000 3.446 1.000 0.976 0.763 0.757 1.000 2.499 2.859 2.406 1.000 0.921 SE 0.090 0.084 0.070 0.090 1.079 0.084 0.076 0.075 0.396 0.451 0.385 0.033 Table A2. Mean scores and standard errors of other exogenous variables. Nature business Age Nature holiday Gender Income Education Heritage membership Dutch nationality Other_European Business motive View publication stats Mean SE 0.107 1.319 0.734 0.514 1.962 2.591 0.224 0.197 0.503 0.069 0.014 .030 0.019 0.022 0.083 0.053 0.018 0.017 0.022 0.011