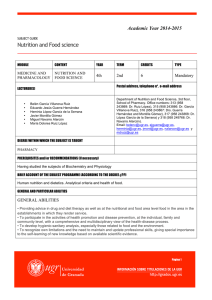

ARTICLE IN PRESS European Journal of Oncology Nursing (2005) 9, S64–S73 www.elsevier.com/locate/ejon Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition Michelle Davies Haematology Department, Christie Hospital, Manchester, UK KEYWORDS Cancer-associated malnutrition; Screening; Assessment; Nurse; Cost Summary Up to 85% of all patients with cancer develop clinical malnutrition, which negatively affects patients’ response to therapy, increases the incidence of treatment-related side effects and can decrease survival. Early identification of patients who are malnourished or at risk of malnutrition can promote recovery and improve prognosis. In addition, early nutritional intervention is cost effective, as it reduces complication rates and length of hospital stay. The development and use of screening and assessment tools is essential for effective nutritional intervention and management of patients with cancer. Nutritional screening aims to identify patients who are malnourished or at significant risk of malnutrition. Patients identified through screening require referral to a dietician or specialist in nutrition for an in-depth nutritional assessment, involving examination of medical, dietary, psychological and social history, physical examination, anthropometry and biochemical testing. Interventions initiated after nutritional assessment should be tailored to the individual and take into consideration the patient’s prognosis. Nutritional care is a fundamental aspect of nursing practice and nurses are ideally placed to play an essential role in the early detection and screening of malnutrition in patients with cancer. & 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Zusammenfassung Bei bis zu 85 % aller Patienten mit Krebserkrankungen treten klinische Zeichen einer Mangelernährung auf. Eine Mangelernährung beeinträchtigt das Ansprechen der Patienten auf die Therapie, erhöht die Inzidenz von behandlungsassoziierten Nebenwirkungen und kann zu einer Verkürzung der Lebensdauer führen. Eine möglichst frühzeitige Identifizierung von Patienten, die an Mangelernährung leiden oder bei denen ein Risiko für eine Mangelernährung besteht, kann eine klinische Besserung fördern und die Prognose positiv beeinflussen. Darüber hinaus sind ernährungstherapeutische Maßnahmen kosteneffektiv, da sie die Häufigkeit von Komplikationen verringern und die Krankenhausverweildauer verkürzen. Die Entwicklung und Anwendung von Screening- und Beurteilungsmethoden ist für die Wirksamkeit ernährungstherapeutischer Maßnahmen und das Management von Krebspatienten von entscheidender Bedeutung. Tel.: +44 0 161 446 8093. E-mail address: [email protected]. 1462-3889/$ - see front matter & 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2005.09.005 ARTICLE IN PRESS Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition S65 Das Ziel eines Ernährungs-Screenings besteht darin, Patienten zu erkennen, die an Mangelernährung leiden oder bei denen ein Risiko für eine Mangelernährung besteht. Patienten, die mittels Screening identifiziert werden, müssen eine Diätberatung oder einen Ernährungsspezialisten aufsuchen, um sich einer gründlichen Evaluation des Ernährungszustandes zu unterziehen, einschließlich der Erhebung der medizinischen, diätetischen, psychologischen und sozialen Anamnese, einer körperlichen Untersuchung sowie der Bestimmung anthropometrischer und klinisch-chemischer Parameter. Therapeutische Interventionen, die sich aus der Evaluation des Ernährungszustandes ergeben, müssen auf den einzelnen Patienten zugeschnitten sein und die Prognose des Patienten berücksichtigen. Ernährungstherapeutische Maßnahmen bilden einen wesentlichen Aspekt der Berufspraxis von Krankenpflegekräften. Diese sind ideal dafür geeignet, eine Schlüsselrolle bei der Früherkennung und dem Screening einer Mangelernährung bei Krebspatienten zu spielen. & 2005 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction to nutritional screening and assessment It is widely recognised that diet and nutrition play significant roles throughout the clinical course of cancer. It has been reported that up to 85% of all cancer patients develop a degree of clinical malnutrition (Kern and Norton, 1988; Ollenschlager et al., 1991). Approximately half of patients have lost at least 5% of their pre-illness weight at presentation, and virtually all patients with advanced cancer display this degree of weight loss (Nixon et al., 1980). The pattern of weight loss seen in cancer is different from that in patients who lose weight through starvation, and forms part of the syndrome of cancer cachexia. Cachexia is characterised by anorexia, changes in taste perception, early satiety and fatigue, in addition to weight loss (Fearon, 1992). Cachexia is a complex and multifaceted syndrome; causal factors include host inflammatory mediators produced in response to the tumour, tumour-derived catabolic factors and anticancer therapy (Barber et al., 1999; Tisdale, 1999). The risk of malnutrition and its severity are affected by the tumour type, stage of disease and the antineoplastic therapy applied (Shike and Brennan, 1989). Moreover, cancer-associated malnutrition has many consequences, including increased risk of infection, reduced wound healing, reduced muscle function and poor skin turgor resulting in skin breakdown (Langer et al., 2001). Malnutrition can also affect the patient’s response to therapy (DeWys et al., 1980) and increase the incidence of treatment-related side effects. It is thought that death can be attributed to cancer cachexia in a significant proportion of patients (Buss, 1987). In view of the serious consequences of poor nutritional status, early identification of patients with, or at risk of developing, malnutrition is essential to enable appropriate intervention and improve nutritional status. Clinical studies have shown that early intervention is necessary if nutritional support is to improve outcome (Ottery, 1994; Nitenberg and Raynard, 2000; MacDonald, 2003). Patients may present with obvious cancerassociated malnutrition or be at risk of developing malnutrition during the course of their disease. Screening of all patients can detect those at risk, and prevent the onset or progression of malnutrition through appropriate interventions. Two main evaluation processes exist to identify patients with, or at risk of malnutrition: nutritional screening and nutritional assessment. Nutritional screening is the first step, and should be applied to all patients with cancer. For hospitalised patients, screening should be undertaken immediately following admission, and at regular intervals thereafter. Patients attending hospital regularly as outpatients also require regular screening; this can be performed during hospital visits and in the community. Primary care patients are also at risk of developing malnutrition and should be screened in the home by a community healthcare professional. Screening should ideally be undertaken by a nurse and be a quick, simple method of identifying patients with, or at risk of developing malnutrition. The relevant patients should then be referred to a dietician or clinical nurse specialist (Fig. 1) for a more detailed assessment of their nutritional status. Nutritional screening and assessment will be discussed in detail in this article. Nutritional screening The use of suitable nutritional screening methods is fundamental for effective nutritional intervention ARTICLE IN PRESS S66 M. Davies Nutritional screening (might include): • Body mass index (BMI)/body weight • Unintended weight loss • Impaired food intake • Treatment plan • Disease severity Refer to dietitian or clinical nurse specialist Nutritional assessment (might include): • History (medical, dietary, social) • Physical examination • Anthropometry (e.g. weight, height, BMI, muscle strength, muscle loss) • Biochemical tests (blood, urine) Figure 1 Nutritional screening and assessment of patients with cancer. Screening identifies patients with, or at risk of developing, malnutrition, who should then be referred to a dietetic specialist for more detailed assessment. and management in patients with cancer. Nutritional screening aims to provide an indication of the nutritional status of patients and assess whether their nutritional needs are being met, thereby identifying patients who are malnourished or at significant risk of malnourishment. Vulnerable patients can then be referred to a specialist for detailed assessment. To achieve this, it has been recommended that nutritional screening should be performed on all patients on admission to hospital, and at regular intervals thereafter to ensure any nutritional decline due to therapy or disease progression is identified as early as possible and can be dealt with (Holder, 2003). Outpatients are equally at risk, and require similar consideration; therefore, screening should be incorporated into hospital appointments or performed by healthcare workers during home visits. In a hospital environment, nutritional screening should be performed by nurses who are in daily contact with the patient. In the community, this process could be incorporated into standard patient health reviews and nursing care plans. Essentially, nutritional screening should use a tool that is quick and easy to perform by the nursing staff. It should be sensitive, reliable and relevant to the target group, and the results should guide non-dietetic healthcare professionals, for example, nurses, to the appropriate course of action, such as referral to a specialist dietician or clinical nurse specialist, if this is indicated. Although no standardised nutritional screening tool has been designed specifically for use in patients with cancer, several exist and have been shown to be effective in different patient groups including primary care patients, hospital inpatients and the elderly (Jensen, 1992; Russell, 2000; Green and Watson, 2005). The most commonly used screening tool is the Malnutrition Universal Screening Tool (MUST) (Stratton et al., 2004). Nutritional screening tools typically use a questionnaire format to examine factors known to lead to, or be associated with, malnourishment. Such tools generally focus on body weight, weight loss and appetite. It has been suggested (Lennard-Jones et al., 1995) that patients should routinely be asked the following four questions, which make up the core principles of nutritional screening: Have you unintentionally lost weight recently? Have you been eating less than usual? What is your normal weight? How tall are you? The latter enable Body Mass Index (BMI) to be calculated (see below). Additional observations, such as loose clothing or jewellery, can also alert the healthcare professional ARTICLE IN PRESS Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition to recent weight loss, and these findings may be particularly useful in patients who cannot be weighed. Nutritional screening tools Several screening tools have been developed over the past two decades, however, until recently, most have been too complex to be useful in routine clinical practice. Ideally, a nutritional screening tool will achieve a balance between ease of use and the provision of sufficient data, to alert healthcare professionals to the appropriate course of action. The MUST has been developed by the British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition in the UK and is commonly used in many patient types (Table 1) (Stratton et al., 2004). This tool is very reliable and has been validated in a range of healthcare settings by different healthcare professionals (Stratton et al., 2004), although its value has not yet been established in patients with cancer. A series of charts allows for rapid categorisation of patients based on BMI and weight loss, and for conversion of knee height into stature, where necessary. The tool can also be adapted to specific situations and local needs, such as how to proceed if the individual’s height and weight cannot be reliably or easily obtained. MUST also covers the management of obese patients and those requiring special diets. Other nutrition screening tools include The Nutrition Risk Index (Wolinsky et al., 1990), used by dieticians and Table 1 S67 nurses, and the Burton Score (Russell et al., 1998). With certain tools, an appropriate course of action can be suggested, dependent on the score achieved. Although the core principles of nutritional screening apply to all patients, some patient groups may require tailor-made screening tools. Rypkema et al. (2004) developed a screening tool for use in elderly patients, which included screening for malnutrition, dehydration and dysphagia upon admission, followed by immediate intervention where required. Implementing this protocol was found to prevent weight loss and achieve weight gain, which was associated with a significantly lower incidence of hospital-acquired infections compared with standard care, demonstrating the value of early nutritional screening. The two simplest measures of the patient’s body size and form, which will give indications of nutritional status, are height and weight. When a patient’s weight and height are known, the BMI can be calculated and used to identify patients at risk of malnutrition. BMI ¼ weight (kg)/height2 (m2), and is an indicator of the chronic protein and energy status of the individual. The BMI can be compared with standard cut-off points (Table 2) that classify individuals as severely underweight, underweight, normal, overweight, obese and morbidly obese. Although widely used, the BMI has several limitations, which must be considered when using it to assess nutritional status. For example, the cutoff points are arbitrary and based on young, healthy adults, and may not be appropriate for patients Steps for malnutrition universal screening tool. Assessment/action Score Step 1 BMI (kg/m ) 420 ¼ 0, 18.5720 ¼ 1, o18.5 ¼ 2 Step 2 Weight loss (unplanned weight loss in past 3–6 months) o5% ¼ 0, 5–10% ¼ 1, 410% ¼ 2 Step 3 Acute disease effect (acute illness with no nutritional intake 45 days) 2 Step 4 Overall risk of malnutrition (add scores from Steps 1–3) 0 ¼ low risk, 1 ¼ medium risk, X2 ¼ high risk Step 5 Management guidelines provided for each risk category (low risk: routine clinical care; medium risk: observe, treat if no improvement; high risk: treat, unless detrimental or no benefit expected) 2 Instructions given for alternative measurments and use of subjective criteria if weight and height cannot be obtained. ARTICLE IN PRESS S68 Table 2 M. Davies BMI cut-off points. BMI (kg/m2) Interpretation o16 16–19 20–25 26–30 31–40 440 Severely underweight Underweight Normal range Overweight Obese Morbidly obese with cancer due to the effects of the disease. Hydration status can have a large impact on body weight; some patients with cancer experience oedema, with changes in normal intracellular fluid to protein ratio occurring either as a result of disease or treatment. This can give an incorrect weight and, therefore, BMI. In the case of large, solid tumours, tumour mass may contribute o10% of total body mass in children and 4–5% in adults, which can also mask loss of weight and lean body mass. Individuals with extremes of stature may have a BMI that lies outside the normal range for the population as a whole, while still having good nutritional status and stable weight. Thus, additional methods of nutritional screening might be necessary, however, these also have limitations. Measurement of the patient’s weight as a percentage of their ideal body weight can be used, although this is subject to errors, as establishment of standard values for ideal weight is problematic. For these reasons, measurement of weight loss, such as current body weight compared with usual weight is used most often; it also has the advantage of using the patient’s usual weight as the comparator. Assessment of changes in body weight over time can be a more informative indicator of nutritional decline. Although affected by short-term fluctuations, such as changes in fluid balance, assessment of changes over time take into account the time in which weight loss has occurred; this has been shown to be important in the assessment of nutritional status, with rapid weight loss indicative of more severe malnutrition (Ottery, 1995; Nitenberg and Raynard, 2000). Nutritional assessment All patients identified as malnourished, or at risk of malnutrition following nutritional screening, should be referred for a complete nutritional assessment performed by an appropriate healthcare profes- sional, such as a dietician or other specialist in nutrition. Nutritional assessment is more in-depth and complex than screening, and involves the use of several measures to determine nutritional status. The purposes of such assessments are to confirm the presence, extent, degree of severity, and type of malnutrition; determine the nutritional needs of the patient and the nutritional support required; provide the basis of the treatment plan and monitor the progress of those receiving nutritional support, and to determine whether their nutritional needs are being met. Nutritional assessment should accurately determine the nutritional status of the patient. Although there is no generally accepted method of assessing nutritional status, the assessment should determine whether the individual is in a good or bad state of nutrition. Aspects such as the patient’s physiological requirements, nutritional intake, body composition and functional status should be considered, and the findings interpreted together. Individual circumstances will dictate the parameters and assessment methods used; these usually encompass a combination of objective and subjective parameters, including: clinical considerations physical considerations psychological considerations dietary considerations anthropometric considerations biochemical and haematological considerations. The initial assessment should serve as the basis for planning nutritional intervention, and assessment should be repeated regularly to determine the efficacy of nutritional support. The basic assessment techniques are as follows: 1. history taking (medical, psychological, dietary and social history) 2. physical examination (disease status, fluid balance and functional assessment) 3. anthropometry (weight, height and body composition) 4. biochemical assessment (blood and urine parameters). Nutritional assessment is most informative when performed repeatedly to assess changes over time. Medical, dietary and social history A review of the patient’s medical history may identify high-risk conditions, as well as highlight ARTICLE IN PRESS Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition current and prior illnesses that may impact on nutritional status. A thorough dietary history is essential and should include assessment of current food and fluid intake, previous intake, and any recent changes should be noted. From this, an indication of the patient’s macro- and micronutrient intakes can be gained. In cases where deficits are detected, some form of supplementation may be advised. In addition, the assessment should aim to detect food aversions, intolerances and problems with feeding, such as taste changes (Baker et al., 2002). The patient’s social history may also provide insights into failure or inability to obtain or prepare adequate food. Psychological problems in response to illness can also affect nutritional intake, and therefore, should also be considered. In cases where problems are apparent, referral to a specialist in this area can benefit the patient. Physical examination Reduced skeletal muscle mass and function are also good indicators of malnutrition. Pre-operative grip strength has been shown to correlate with postoperative complications and poor surgical outcome (Mahalakshmi et al., 2004). However, grip strength can be distorted by concurrent diseases, such as arthritis or conditions causing impaired muscle function, which must be considered when performing this type of physical examination. Exercise tolerance, based on the patient’s opinion of their ability to carry out normal day-to-day tasks, or objective assessment of the time taken to complete assigned physical tasks, is also an indicator of physical function. Respiratory muscle strength can be assessed by measurement of lung function, for example, peak flow, although this is rarely carried out in practice. Immune function is impaired in malnourished individuals and can be used to indirectly assess nutritional status (Hudgens et al., 2004): total lymphocyte counts of o2.0 109/L and o0.9 109/L are indicators of mild and severe malnutrition, respectively. However, some haematological malignancies, immunosuppressive drugs and infections affect lymphocyte counts, limiting the usefulness of this technique. Again, this is rarely used as an assessment technique in practice. S69 water (Sarhill et al., 2003). Weight changes, when measured accurately and regularly, are valuable indicators of nutritional risk, and are considered more informative than one-off assessments of BMI. Weight changes provide information on the duration and extent of weight loss over time, and as such are highly valuable. Although, weight and height are among the simplest and least invasive anthropometric measurements, there are occasions when they are less useful, for example in fluid imbalances or when patients are unable to stand. Several techniques are available to measure body composition; however, all have limitations with regard to applicability to nutritional assessment, as reviewed by Jensen (1992). For example, BMI cutoff points are arbitrary and based on young, healthy adults; large tumours can contribute considerably to body mass; hydration status can affect body composition. Repeated, direct measurement of body fat or lean tissue mass (mid-upper arm circumference, triceps skin-fold) allows mapping of changes in an individual, and may be particularly important in patients with cancer, in whom large tumours can contribute to body weight. Biochemical assessment The most common biochemical measurements used to assess nutritional status are blood parameters such as serum albumin, pre-albumin and iron levels. Biochemical and haematological parameters are subject to homeostatic mechanisms and may be altered by underlying disease and/or treatment. This can make interpretation difficult and lead to false conclusions regarding nutritional status. For example, in cancer, serum albumin often reflects acute effects of treatment or disease, rather than nutritional status, therefore albumin alone is not a good indicator of nutritional status. Biochemical assessments can also be expensive and are often not performed if interpretation is problematic. However, abnormal measurements of markers, such as serum ferritin, add value to the nutritional assessment, particularly when other parameters are difficult to interpret. Cancer-specific screening and assessment Anthropometry Anthropometric assessment (e.g. BMI, mid-upper arm circumference, skin-fold thickness) includes an appraisal of the patient’s weight, height and body composition, that is, lean body mass, fat stores and Cancer cachexia requires specific methods of screening and assessment, owing to the impact of not only the tumour on nutritional status, but also to that of the anticancer treatments. Several tools have been developed specifically for patients with ARTICLE IN PRESS S70 cancer, including the Oncology Screening Tool (OST) (MSKCC, Clinical Dietitian Staff 1994–1995), which can be used in different clinical settings, such as inpatient or outpatient clinics, or at home. The OST, which is normally conducted by a nurse or dietician, screens patients for weight loss and a 2week or more history of decreased food intake, nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, mouth sores and difficulty in chewing or swallowing. Patients are classified as low or medium-to-high risk, with the latter group receiving a full nutritional assessment by a dietician within 24 h. Confirmation of patients with low-risk status is performed on day 6, and patients are reclassified if necessary. The Modified Patient Generated Subjective Global Assessment may also compose part of the complete nutritional assessment (Ottery, 1996). The patient completes the first part of the assessment, which surveys their weight (current, 1 month previously, 6 months previously), height, change in food intake over the past month, symptoms that have affected eating habits (lack of appetite, nausea, constipation, taste, pain, dry mouth), and general activity and function (normal, fairly normal, able to do a little, rarely out of bed). The healthcare professional then assigns scores to the domains assessed by the patient and completes worksheets assessing weight loss, disease category and comorbidities, metabolic demand, and physical exam. A three-level rating is determined (Stages A, B or C) and the appropriate form of nutritional intervention established (Ottery, 1996). The functional capacity of the patient should be assessed in conjunction with nutritional assessment to ensure that the nutritional intervention is tailored to, and appropriate for, the individual patient. The Karnofsky Performance Status (KPS) Scale is widely used to measure physical functioning, as well as medical care requirements in patients with cancer (Yates et al., 1980; Mor et al., 1984; however, it has been postulated that the KPS may have difficulty assessing clinical change over time (O’Dell et al., 1995) and the procedure for scoring the instrument has not been validated (Schag et al., 1984). The scale ranges in 10-point increments from 100 (normal, no complaints, no evidence of disease) through to 0 (dead). A reduction in function is generally related to the cumulative physiological and psychological effects of the disease, while performance status has been shown to be an important predictor of response to therapy and survival (Maurer and Pajak, 1981). The assessment of a patient’s quality of life provides important data regarding the patient’s perception of their health, as well as information M. Davies on the impact of malnutrition and nutritional support, and whether this is appropriate for the patient. The European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Core Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-30) is a validated, reliable measure of quality of life in patients with cancer (Aaronson et al., 1993). The instrument contains five functional scales (physical, role, emotional, cognitive and social), three symptom scales (fatigue, pain and emesis) and one global scale. These three scales together produce a score in the range 0–100. Quality of life questionnaires specific for certain cancers have also been developed (Kaptein et al., 2005; Avis et al., 2005). Potential benefits of nutritional screening The key advantage of nutritional screening is that it can identify patients at risk of, or experiencing, nutritional deficits before progression to malnutrition. Therefore, screening may help to prevent the onset of malnutrition. Early identification allows for early intervention with nutritional supplementation to prevent malnutrition and the ‘vicious circle’ of disease from developing. In contrast, in patients with advanced cancer, nutritional intervention may only achieve weight stabilisation, rather than reversal of weight loss, suggesting early intervention is more beneficial to the patient (MacDonald, 2003). Nutritional support is known to have significant advantages for the patient. Through improving nutritional status, nutritional support has been shown to improve many outcomes, including immune function, survival and quality of life (Tchekmedyian, 1995; Bozzetti, 2001; Rypkema et al., 2004). Furthermore, early nutritional interventions have been shown to reduce morbidity and mortality, as well as healthcare costs (Reilly et al., 1988; Chima et al., 1997; Rypkema et al., 2004). Nutritional screening may also facilitate recovery: for example, diaphragmatic and other respiratory muscle dysfunction can contribute to respiratory arrest, the need for intubation or the inability to extubate a patient post-operatively or during oncological complications. Importantly, this deterioration in functional status can result in delays in therapeutic intervention or even the exclusion of therapies due to standard protocol exclusion criteria of performance status. Survival benefits following chemotherapy have also been identified in patients with gastrointestinal cancer who had ARTICLE IN PRESS Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition not lost weight at presentation compared with those who had (Andreyev et al., 1998). From an economic standpoint, early nutritional intervention has been shown to be cost-effective, as well as beneficial. Reilly et al. (1988) conducted a retrospective study of 771 patient records in two acute care hospitals and concluded that the costs associated with malnutrition, in cancer and noncancer patients, including length of hospital stay and complication rate, warranted early detection and aggressive treatment. Rypkema et al. (2004) showed that early nutritional intervention in older patients in hospital is cost effective and beneficial to the patient, achieving weight gain and lowering hospital-acquired infections. It has also been shown that patients identified as at risk of malnutrition require a significantly longer hospital stay and have higher costs and home healthcare needs than those not at risk of malnutrition (Chima et al., 1997). These studies highlight the importance and benefits of early nutritional screening, not only to the patient, but also to the healthcare provider. Continued monitoring of nutritional status Nutritional screening and assessment do not end with the instigation of nutritional support. Regular monitoring should be performed to ensure that nutritional intervention is effective and the patient is not experiencing further nutritional decline or complications. Nutritional support programmes implemented after nutritional screening and assessment should be tailored to the individual and take into consideration the patient’s prognosis, treatment, gut function, ability to feed, religious and personal taste preferences. Options for nutritional support include oral, enteral feeding tube, and total parenteral nutrition. The method and frequency of continued nutritional assessment will differ between patients and depend on their clinical condition, stability and type of nutritional support. The role of the nurse in nutritional screening Nurses play a crucial role in the early detection of nutritional decline, as well as the identification of patients at risk of developing malnutrition. Thorough nutritional screening should ideally be carried out by nurses when patients are admitted to hospital, and throughout their hospital stay, in S71 order to effectively plan their nutritional care. Importantly, nursing staff are on-hand and have contact with patients on a daily basis, making them ideally placed to identify changes in patient’s food intake and general well-being. Regular monitoring of patients receiving care in their own home should not be ignored as these patients may be at particularly high risk of malnutrition. Nurses are also ideally placed to screen such patients for signs of malnutrition. For example, nutritional screening, including assessment of weight loss, could be easily incorporated into domestic visits to primary care patients. Ideally, weighing should be performed weekly, and can be particularly informative if done so at the same time of day, when the patient is wearing the same clothes, and using the same scales. More regular weighing could cause the patient to become anxious about their weight and upset if poor progress or decline is evident (Anthony and Montagna, 2000). Nurses should monitor factors that contribute to decreased food intake, such as nausea, vomiting, and pain, and ensure that factors contributing to debilitation levels are considered and corrected (Dell, 2002). Early identification of patients with declining nutritional status allows the nurse to alert the appropriate expert, such as the doctor, clinical nurse specialist or dietician, before malnutrition develops. Through close, regular monitoring of patients, nurses can also ensure that the nutritional support strategy employed is effective, and the correct course of action is taken to tailor nutritional support to the individual patient. Successful nutritional support can be ensured through liaison with other healthcare professionals, such as doctors and dieticians (Holder, 2003). Conclusions and recommendations Careful evaluation of nutritional status through nutritional screening and assessment is essential to identify malnourished patients or those at risk of becoming malnourished. Through screening and assessment, early nutritional interventions can be implemented, which can improve response to treatment, performance status, quality of life and reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with cancer. Nurses play a vital role in the identification of malnourished patients, the continued assessment of those at risk of developing malnutrition, and the evaluation of the efficacy of nutritional intervention strategies. Screening is, therefore, not only important for the patient–in whom nutritional support can improve outcomes such as ARTICLE IN PRESS S72 quality of life, decrease length of hospital stay and achieve psychological benefits—but is also beneficial to the healthcare provider. Early interventions, made possible as a result of screening, can be of considerable financial benefit to the healthcare provider, reducing costs through shorter periods of hospitalisation, fewer complications and other indirect costs. References Aaronson, N.K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N.J., Filiberti, A., Fletchtner, H., Flieshman, S.B., de Haes, J.C., 1993. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer QLQ-C30: a quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 85 (5), 365–376. Andreyev, H.J., Norman, A.R., Oates, J., Cunningham, D., 1998. Why do patients with weight loss have a worse outcome when undergoing chemotherapy for gastrointestinal malignancies? European Journal of Cancer 34 (4), 503–509. Anthony, P., Montagna, P., 2000. Nutrition management. In: Fieler, V.K., Hanson, P.A. (Eds.), Oncology Nursing in The Home. Oncology Nursing Society, Pittsburg (Chapter 8). Avis, N.E., Crawford, S., Manuel, J., 2005. Quality of life among younger women with breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 23 (15), 3322–3330. Baker, F., Denniston, M., Zabora, J., Polland, A., Dudley, W.N., 2002. A POMS short form for cancer patients: psychometric and structural evaluation. Psycho-oncology 11 (4), 273–281. Barber, M.D., Ross, J.A., Fearon, K.C., 1999. Cancer cachexia. Surgical Oncology 8, 133–141. Bozzetti, F., 2001. Nutrition and gastrointestinal cancer. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 4, 541–546. Buss, C.L., 1987. Nutritional support of cancer patients. Primary Care 14 (2), 317–335. Chima, C.S., Barco, K., Dewitt, M.L., Maeda, M., Teran, J.C., Mullen, K.D., 1997. Relationship of nutritional status to length of stay, hospital costs, and discharge status of patients hospitalized in the medicine service. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 97 (9), 975–978. Dell, D.D., 2002. Cachexia in patients with advanced cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing 6 (4), 235–238. DeWys, W.D., Begg, C., Lavin, P.T., Band, P.R., Bennett, J.M., Bertino, J.R., Cohen, M.H., Douglass Jr., H.O., Engstrom, P.F., Ezdinli, E.Z., Horton, J., Johnson, G.J., Moertel, C.G., Oken, M.M., Perlia, C., Rosenbaum, C., Silverstein, M.N., Skeel, R.T., Sponzo, R.W., Tormey, D.C., 1980. Prognostic effect of weight loss prior to chemotherapy in cancer patients. Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American Journal of Medicine 69 (4), 491–497. Fearon, K.C.H., 1992. The mechanisms and treatment of weight loss in cancer. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 51, 251–265. Green, S.M., Watson, R., 2005. Nutritional screening and assessment tools for use by nurses: literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 50, 69–83. Holder, H., 2003. Nursing management of nutrition in cancer and palliative care. British Journal of Nursing 12 (11), 667–668 670, 672–674. Hudgens, J., Langkamp-Henken, B., Stechmiller, J.K., Herrlinger-Garcia, K.A., Nieves Jr., C., 2004. Immune function is impaired with a mini nutritional assessment score indicative M. Davies of malnutrition in nursing home elders with pressure ulcers. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 28 (6), 416–422. Jensen, M.D., 1992. Research techniques for body composition assessment. Journal of the American Dietetic Association 92, 454–460. Kaptein, A.A., Morita, S., Sakamoto, J., 2005. Quality of life in gastric cancer. World Journal of Gastroenterology 11 (21), 3189–3196. Kern, K.A., Norton, J.A., 1988. Cancer cachexia. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition 12 (3), 286–298. Langer, C.J., Hoffman, J.P., Ottery, F.D., 2001. Clinical significance of weight loss in cancer patients: rationale for the use of anabolic agents in the treatment of cancer-related cachexia. Nutrition 17 (1 Suppl), S1–S20. Lennard-Jones, J.E., Arrowsmith, H., Davison, C., Denham, A.F., Micklewright, A., 1995. Screening by nurses and junior doctors to detect malnutrition when patients are first assessed in hospital. Clinical Nutrition 14, 336–340. MacDonald, N., 2003. Is there evidence for earlier intervention in cancer-associated weight loss? The Journal of Supportive Oncology 1 (4), 279–286. Mahalakshmi, V.N., Ananthakrishnan, N., Kate, V., Sahai, A., Trakroo, M., 2004. Handgrip strength and endurance as a predictor of postoperative morbidity in surgical patients: can it serve as a simple bedside test? International Surgery 89 (2), 115–121. Maurer, L.H., Pajak, T.F., 1981. Prognostic factors in small cell carcinoma of the lung: a cancer and leukemia group B study. Cancer Treatment Reports 65 (9–10), 767–774. Mor, V., Laliberte, L., Morris, J.N., Wiemann, M., 1984. The Karnofsky performance status scale. An examination of its reliability and validity in a research setting. Cancer 53 (9), 2002–2007. MSKCC Adult Oncology Screening Tool, Clinical Dietitian Staff 1994–1995, Food Service Department, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Nitenberg, G., Raynard, B., 2000. Nutritional support of the cancer patient: issues and dilemmas. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 34, 137–168. Nixon, D.W., Heymsfield, S.B., Cohen, A.E., Kutner, M.H., Ansley, J., Lawson, D.H., Rudman, D., 1980. Protein-calorie undernutrition in hospitalized cancer patients. American Journal of Medicine 68 (5), 683–690. O’Dell, M.W., Lubeck, D.P., O’Driscoll, P., Matsuno, S., 1995. Validity of the Karnofsky performance status in an HIV infected sample. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome Human Retrovirology 10 (3), 350–357. Ollenschlager, G., Viell, B., Thomas, W., Konkol, K., Burger, B., 1991. Tumor anorexia: causes, assessment, treatment. Recent Results in Cancer Research 121, 249–259. Ottery, F.D., 1994. Cancer cachexia: prevention, early diagnosis, and management. Cancer Practice 2, 123–131. Ottery, F.D., 1995. Supportive nutrition to prevent cachexia and improve quality of life. Seminars in Oncology 22 (2, Suppl 3), 98–111. Ottery, F., 1996. Definition of standardised nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition 12, S15–S19. Reilly Jr., J.J., Hull, S.F., Albert, N., Waller, A., Bringardener, S., 1988. Economic impact of malnutrition: a model system for hospitalized patients. Journal of Parenteral and Enteral nutrition 12 (4), 371–376. Russell, L., 2000. Malnutrition and pressure ulcers: nutritional assessment tools. British Journal of Nursing 9, 194–196 198, 200. ARTICLE IN PRESS Nutritional screening and assessment in cancer-associated malnutrition Russell, L., Taylor, J., Brewitt, J., Ireland, M., Reynolds, T., 1998. Development and validation of the burton score: a tool for nutritional assessment. Journal of Tissue Viability 8 (4), 16–22. Rypkema, G., Adang, E., Dicke, H., Naber, T., de Swart, B., Disselhorst, L., Goluke-Willemse, G., Olde Rikkert, M., 2004. Cost-effectiveness of an interdisciplinary intervention in geriatric inpatients to prevent malnutrition. The Journal of Nutrition, Health and Aging 8 (2), 122–127. Sarhill, N., Mahmoud, F.A., Christie, R., Tahir, A., 2003. Assessment of nutritional status and fluid deficits in advanced cancer. The American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Care 20, 465–473. Schag, C.C., Heinrich, R.L., Ganz, P.A., 1984. Karnofsky performance status revisited: reliability, validity, and guidelines. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2, 187–193. Shike, M., Brennan, M.F., 1989. Supportive care of the cancer patient. In: DeVita, V.T., Hellman, S., Rosenberg, S.A. (Eds.), Cancer: Principles and Practice of Oncology. Philadelphia, JB Lippincott, pp. 2029–2044. S73 Stratton, R.J., Hackston, A., Longmore, D., Dixon, R., Price, S., Stroud, M., King, C., Elia, M., 2004. Malnutrition in hospital outpatients and inpatients: prevalence, concurrent validity and ease of use of the ‘malnutrition universal screening tool’ (‘MUST’) for adults. British Journal of Nutrition 92 (5), 799–808. Tchekmedyian, N.S., 1995. Costs and benefits of nutrition support in cancer. Oncology 9 (11 Suppl), 79–84. Tisdale, M.J., 1999. Wasting in cancer. Journal of Nutrition 129 (1S Suppl), 243S–246S. Wolinsky, F.D., Coe, R.M., McIntosh, W.A., Kubena, K.S., Prendergast, J.M., Chavez, M.N., Miller, D.K., Romeis, J.C., Landmann, W.A., 1990. Progress in the development of a nutritional risk index. Journal of Nutrition 120 (Suppl. 11), 1549–1553. Yates, J.W., Chalmer, B., McKegney, F.P., 1980. Evaluation of patients with advanced cancer using the Karnofsky performance status. Cancer 45 (8), 2220–2224.