The 36-Hour Day A Family Guide to Caring for Persons with Alzheimer Disease, Related Dementing Illnesses, and Memory Loss in Later Life (A Johns Hopk

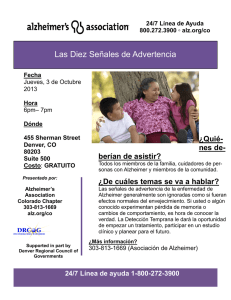

Anuncio