COMPAINE & HOAG - Factors Supporting and Hindering New Entry in Media Markets A Study of Media Entrepreneurs

Anuncio

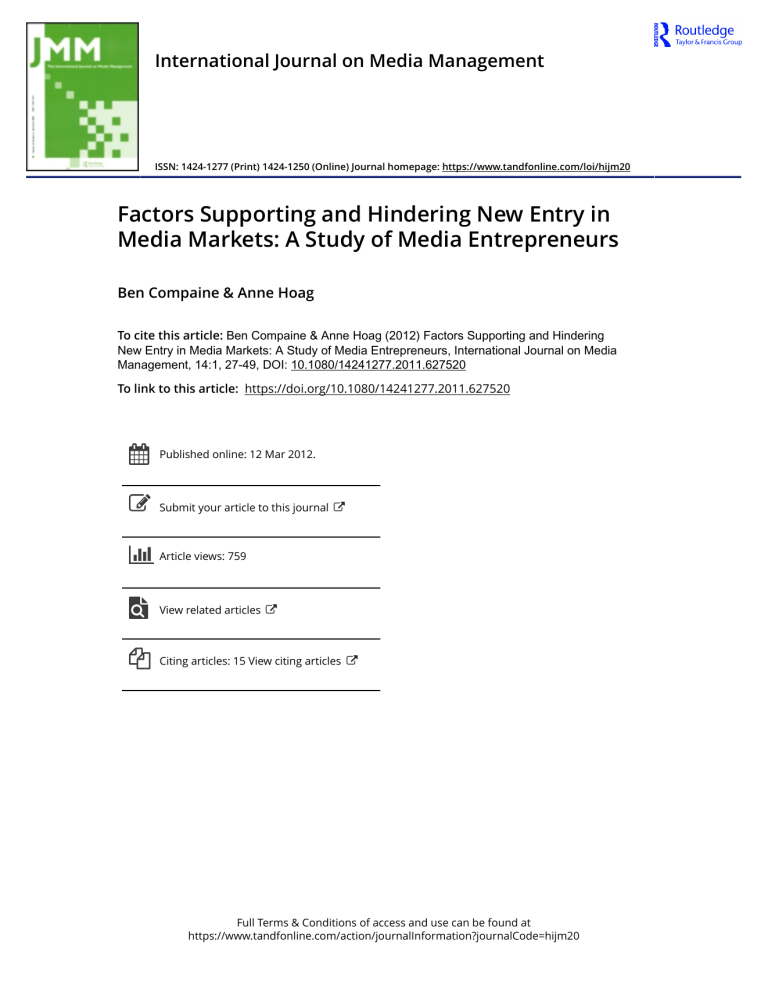

International Journal on Media Management ISSN: 1424-1277 (Print) 1424-1250 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hijm20 Factors Supporting and Hindering New Entry in Media Markets: A Study of Media Entrepreneurs Ben Compaine & Anne Hoag To cite this article: Ben Compaine & Anne Hoag (2012) Factors Supporting and Hindering New Entry in Media Markets: A Study of Media Entrepreneurs, International Journal on Media Management, 14:1, 27-49, DOI: 10.1080/14241277.2011.627520 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14241277.2011.627520 Published online: 12 Mar 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 759 View related articles Citing articles: 15 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hijm20 The International Journal on Media Management, 14:27–49, 2012 Copyright © Institute for Media and Communications Management ISSN: 1424-1277 print/1424-1250 online DOI: 10.1080/14241277.2011.627520 Factors Supporting and Hindering New Entry in Media Markets: A Study of Media Entrepreneurs BEN COMPAINE Fordham University, USA ANNE HOAG Pennsylvania State University, USA Despite ongoing concern about so-called “big media” erecting barriers to entry, thousands of new media enterprises are formed annually. It raises the question, “What factors support or hinder new entry in media markets?” A study of 30 U.S.-based media entrepreneurs was undertaken to answer the question. For these entrepreneurs, factors that support entry were abundant; and few, if any, barriers exist to entry and to sustained operations. Two sources of support stand out: the effects of technological innovation and so-called “big media,” which, far from erecting barriers, can be a major source of opportunity. A. J. Liebling (1961), the press critic of more than 1/2 century ago, famously said that “Freedom of the press is guaranteed only to those who own one” (p. 30). This summed up the difficulty of having one’s voice heard beyond its vocal range, except for those who had the capital to literally buy the presses. By extension, it suggested that the cost of printing a publication or owning a piece of the strictly allocated broadcast spectrum were major barriers to entry into the media world. Even a modest weekly newspaper or television outlet had substantial upfront costs that required access to financing that strictly limited who could have their content distributed. The implication was that means of production were controlled by a few dominant firms. Much has changed in the intervening years. For instance, technological innovation—especially the spread of the Internet—has, in theory, reduced Address correspondence to Ben Compaine, Department of Communications and Media Management, Fordham University, 5 Ellery Sq., Cambridge, MA 02138. E-mail: [email protected] 27 28 B. Compaine and A. Hoag certain costs of entry and competition. However, criticism of media ownership and a perception that the market power of dominant media firms has only worsened continues into the 21st century (Bagdikian, 2004; Baker, 2007; McChesney, 2008). Some scholars, applying industrial organization and organizational ecology theories, characterize media markets as innovative and competitive in early stages of the lifecycle, inevitably stabilizing, becoming concentrated, and making new entry difficult (van Kranenburg & Hogenbirk, 2006). The properties of media products have not changed in the sense that first copy costs are high, whereas the marginal cost of the second copies are low. To produce a Hollywood feature film, for example, averaged $65.8 million in 2006 (Mohr, 2007), but each film print costs about $1,500 (Tyson, 2000). Yet, the relative highs and lows vis-à-vis production and distribution costs now can both be quite low—“close enough to free to round down,” as Anderson (2009) wrote in conceptualizing “freemium,” which is the idea that production costs in some product categories are so low that the price can be set at free. If he could comment on media markets today, would Liebling (1961) still contend that dominant media firms limit the number and diversity of available viewpoints? The properties of media markets, some would argue, are still problematic. Are there excessive market power and the conduct of a few dominant firms that would override the potential of reduced production and distribution costs? Regulatory impediments are another possible problem in media markets. The 13th annual report of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC; 2009) on video programming competition concluded that consumers enjoyed more choices and better quality in 2006, on the one hand, but described claims by potential competitors that local franchising rules hindered new entry. Yet, it has been pointed out that today’s media markets are more competitive than ever (Compaine, 2005). There are more than 141,000 information industry firms in the United States alone (U.S. Economic Census, 2007), and new entry in media markets is higher than it is in many other industry sectors (Hoag, 2008). Moreover, there is a dynamism in the players at the top of the media pyramid, with some of yesterday’s biggest companies shrinking or disappearing while new participants rise, in part reflecting the changing fortunes of different segments of the media industry. Dominant firms of the 1950s to 1980s, such as Times Mirror Co., Hearst Corporation, and Gannett Co., Inc., have disappeared or shrunk while newer players from newer segments have appeared, such as Comcast® , TM Amazon.com® , and Google (Compaine, 1979; Compaine & Gomery, 2000). Indeed, Noam (2009) highlighted the complexity of media industry competition. On the one hand, concentration doubled between 1984 and 2005. However, by antitrust standards, Noam pointed out it was still low. He also found that there was little cross-sectional convergence among the Media Entrepreneurs 29 50 largest firms—that is, of the four sectors Noam looked at (mass media, information technology, telecommunications, and Internet), none had a presence in all four sectors, and only three had any meaningful presence in as many as three sectors. Meanwhile, media markets are thought to be susceptible to economic downturns, which would suggest further reducing the chances of survival for new and small competitors. Lower U.S. television network advertising sales were blamed on the weakening U.S. economy in 2009, but the causes also likely included the migration of advertising dollars to the Internet (James, 2009) where new entry may be easier. History suggests that demand for media products is not negatively affected by economic downturn when compared to that for other consumer goods. Throughout the 1930s, the time of the last great economic depression, demand for movies rose (Vogel, 2007). ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND THE MEDIA Writing a few years before Liebling (1961), Josef A. Schumpeter (1942/1976), the influential economist and philosopher, used the term creative destruction to describe what he saw as “the essence of capitalism” (p. 104)—the turmoil that must undergird economic expansion, new entry, and a constant flow of innovation. Meeting Liebling, he would say any perceived firm dominance is temporary. In his view, markets are a process, never able to rest in equilibrium. As Reisman (2004) has summarized Schumpeter’s life’s work, it all comes down to three “irreducible constructs”: markets—that is, supply and demand—which constantly change, thanks to enterprise (“restless transformation”) and evolution (“institutional mutation”; p. 1). Schumpeter saw the entrepreneur as, perhaps, a rare, but always present, agent of change—enterprise and evolution. He or she is unique in ability to recognize opportunity where others fail to see it, and will act on that opportunity by entering the market. As Stolper (1994) interpreted Schumpeter, “An entrepreneur is someone who sees that things could be done differently and who actually does something about it . . . ” (p. 59). Schumpeter believed the evidence that market structures did not impede a real entrepreneur. He or she “is a fighter who treats impediments as enemies to be vanquished” (Reisman, 2004, p. 63) and finds alternative means of financing and developing new market tactics. If it is a romantic view, it has, in recent years, attracted renewed support from economists (see Te Velde, 2004), although there are scant data supporting industrial organization models (van Kranenburg & Hogenbirk, 2006). Entrepreneurship is closely entwined with characteristics of uncertainty and risk, as well as barriers to entry (Acs & Audretsch, 2005). Risk is the potential that a conscious action (which could include the choice not to act) will lead to a loss. Although that loss could be time, social standing, physical 30 B. Compaine and A. Hoag well-being, or a number of other measures, in the business context, it often refers to loss of capital. That could be lost wages (as in the opportunity cost of starting a business instead of working for an employer and earning a salary) or loss of investment capital. It has been proposed that entrepreneurs take on risks that others avoid because entrepreneurs may be less risk-adverse than others (Kihlstrom & Laffont, 1979; Knight, 1921). Alternatively, those who engage in entrepreneurial activity may not perceive the risk because they have the knowledge and information they feel are required to bring a successful outcome to their venture (Fiet, 1996). For example, sky diving may seem risky to those who have never done it. However, an experienced sky diver may perceive a low level of risk. Barriers to entry are another element that is frequently a piece of entrepreneurial consideration. Although in some sectors, such as broadcasting, there are regulatory barriers, in almost any venture there could be the hurdle of capital requirements—the need for money to start and maintain the venture (Acs & Audretsch, 2003). If capital needs are low—such as to start a consulting firm—capital needs may not be much of a barrier. However, raising money from potential investors presents a challenge, in many cases, because potential financiers may perceive risk to be greater than does the informed entrepreneur. Entrepreneurial opportunity—whether in the media arena or elsewhere—has been provided with greater nuance by Saravanthy, Dew, Velamuri, and Venkataraman (2003; see also Acs & Audretsch, 2003). They parsed it into subcategories of “opportunity recognition,” “opportunity discovery,” and “opportunity creation.” The differences among these revolve around the obvious existence of a supply and demand and moving to fulfill it (recognition), observation of an obvious supply or demand and moving to fulfill the missing half (discovery), and the observation that neither a supply nor demand exist, thus creating the opportunity through economic interventions. An example of this latter point may be the creation of VisiCalc, an original spreadsheet program for the Apple® II computer. A few years later, the introduction of the MS-DOS computers provided an opportunity for a start-up named Lotus to create a similar program for that market—an example of opportunity discovery. In a time before either of those, a paper manufacturer may have added an improved version of lined spreadsheet paper to its product line for the existing market—an example of recognition. Entrepreneurship of any sort is not a concept that has been closely identified with the media industry in the mass media literature in recent decades. For example, in its 12 years of existence, the International Journal on Media Management has published only a handful of articles about entrepreneurship in the media industry. Geissler and Einwiller (2001) interviewed early e-commerce entrepreneurs in Germany and parts of Media Entrepreneurs 31 Switzerland, looking for a “typology” for such innovators. However, their subjects were not media entrepreneurs but, rather, Internet infrastructure providers, producers of Internet applications, intermediaries, and electronic commerce companies, all of whom were riding the “dot com” boom of the late 1990s. Franke and Schreiner (2002) were even more tangential to media entrepreneurship, focusing on opportunity assessment simply in the form of a venture for a “toolkit.” Bakker (2002), on the other hand, was very much looking at traditional media start-ups of free newspapers, such as the Metro papers. Nonetheless, Bakker used entrepreneur in a very different context conceptualized by Schumpeter (1942/1976). The Metros, and many of the other free papers started from Madrid to Moscow to Philadelphia, were the work of established media companies, often with substantial cash flow from existing operations. Bakker was looking at these firms as representing “the entrepreneur model” of the free newspaper publisher in that “these firms enter a new market with a new product: capitalize and don’t cannibalize (Schibsted published newspapers, but not in markets where they launched free papers)” (p. 181). Rentería (2007) addressed one of the major themes of entrepreneurial studies: barriers to entry. In this case, it was the privatization of the public television channel in Mexico in 1993 that created the first competition for what, up to then, was a commercial television monopoly in that country. Rentería held that to be successful, a new entrant in such a landscape would require vertical and horizontal strategies, as well as content innovation (p. 71). However, none of these studies in the mass media literature focused on the entrepreneurs themselves, their motivations, or their perceptions of the entry barriers, risks, or opportunities. Thus, with the perception of a media industry dominated by big media companies, but tempered by a history of ebb and flow of dominant firms and even media sectors, this study asks two questions: First, in the first decade of the 21st century, are barriers to entry too formidable and the perceived risks too great for potential new entrants in media markets? Second, what factors, if any, support new market entry? These questions fit within a suggested research agenda for media and entrepreneurship—the outcome of a thorough review of literature conducted by Hang and van Weezel (2007). An empirical investigation was conducted using qualitative methods. Thirty U.S.-based media entrepreneurs, from those in planning phases to others whose media enterprises had been operating for a few years, were interviewed between 2006 and 2009. Results of analysis indicate that factors supporting entry are abundant, particularly thanks to seven main effects of technological innovation, and barriers to entry may be more of a perception than a reality. 32 B. Compaine and A. Hoag METHOD The original purpose of this research was not specifically focused on barriers to entry. It was to explore the circumstances under which people get the idea for new media products or services and then further act on those ideas by starting an enterprise. We accepted the broadest notion of entrepreneurial activity, whether it might be characterized as creation, discovery, or recognition. The research questions, therefore, suggested a study of contexts and the meanings and purposes behind entrepreneurs’ perceptions, decisions, and actions. In comparing quantitative and qualitative methods, Guba and Lincoln (1998) pointed out qualitative data collection can preserve context and capture the meaning and purpose behind human behavior where quantitative techniques may strip them away. We used long, semi-structured interviews with individual media entrepreneurs to elicit their experiences and the meanings they attach to those experiences. Interviewing, ethnography, and case study have been used in other research involving media managers acting in their spheres (Achtenhagen & Raviola, 2009; Huang & Heider, 2007) and entrepreneurs in decision-making (McVea, 2009; Vaghely & Julien, 2010). An interview guide (see the Appendix) was developed based on possible processes and concepts surrounding opportunity recognition/discovery/ creation, the decision to exploit the opportunity, the start-up phase, and personal motivations and goals. Although these categories themselves were drawn from a previous large-scale survey, the Panel Study of Entrepreneurial Dynamics (www.psed.isr.umich.edu/psed/data), questions were broadly posed and in open-ended form. Although this study is not built on grounded theory construction (Strauss & Corbin, 1998), we borrowed from its techniques to construct interviews that were designed to encourage interview participants to describe and reflect on their experiences as entrepreneurs. Participants In fitting entrepreneurship into the scope of economic theory and research, Baumol (1993) said the entrepreneur is “at once one of the most intriguing and one of the most elusive in the cast of characters that constitutes the subject of economic analysis” (p. 2). Fortunately, it was relatively easy to recruit as many research participants as were needed—all but one entrepreneur contacted agreed to participate. For our study, a media entrepreneur is defined as a founder of an independent content business that has a clear revenue model, if not a profit incentive. Founders of telephone companies, print shops, or Internet service providers were not recruited because common carriers, by definition, are not independent media content businesses. Media content could be newspapers, books, magazines, television, film/video, recorded music, and a range of Web-based content. Media Entrepreneurs 33 Charmaz (2006) distinguished two kinds of sampling for qualitative analysis: initial sampling and theoretical sampling. Initial sampling is just that—it is a place to start discovery, collecting data from participants who fit basic criteria. An initial sample of 17 was determined theoretical saturation, which means that additional interviews revealed no new experiences, concepts, relationships, or processes. During coding and as categories and relationships emerged from the initial set of interview data, additional “theoretical sampling” led to another 13 interviews with media entrepreneurs recruited and interviewed to both enrich understanding of early findings and to explore the possible negative effects of the economic downturn. For both rounds of interviews, media entrepreneurs were selected in three stages of maturity: those in the start-up process, those recently launching, and those who had been successfully operating for a few years. Failed media entrepreneurs were included, as some of the participants were serial entrepreneurs with a previous failure. Participants were located by various means: press accounts, Internet searches, and researchers’ media connections. We sought entrepreneurs whose products ranged across content markets. Most were mass-market products, but about one-third targeted a niche, including lesbian/gay/bisexual/transgender individuals, women, minorities, business, sports, religion, and youth. A spread of media sectors was sought as well: 29% of the entrepreneurs owned news operations, 30% were in books and periodicals publishing, 23% were in film/video/television, 6% were in recorded music, and 12% were in other content production. Secondary considerations were gender (83% were men) and geographic location of the entrepreneurs (17% resided in the American South, 13% in the West, 33% in the Midwest, and 37% in the Northeast). Table 1 describes the pool of participants. A total of 30 interviews were conducted in person, by telephone, and via video conference. The recorded sessions lasted between 45 min and 2 hr. Interview recordings were transcribed for analysis. Analysis To manage hundreds of pages of transcribed interviews, we followed Huberman and Miles’s (1998) model of interacting processes: data collection, data reduction, data display, and drawing conclusions. Each of us independently reviewed interview transcriptions, coding for emergent concepts and phenomena, categories thereof, patterns, and relationships. We refined our interpretations on distinct categories and relationships with memo-writing, following Charmaz (2006, pp. 72–95). We then compared our interpretations, finding many instances of agreement, and continued our discussion until analysis was finalized. In the data reduction phase, two distinct types of findings emerged, only one of which is the subject of this 34 B. Compaine and A. Hoag TABLE 1 Media Entrepreneurs in the Study Media Entrepreneur M.A. A.B. B.C. W.C. E.L.C. R.D. C.F. E.G. J.G. R.H. G.J. H.J. M.K. B.M. J.M. S.M. B.N. N.N. M.O. J.R. T.S.1 T.S.2 B.S. V.S. K.S. S.T. T.T. J.W.1 J.W.2 J.W.3 Enterprise Description NFL draft blog and fantasy football tool Daily Technology Newscast Animation with songs of Bible verses Football blog Book publisher targeting tween and teen girls Connecticut markets weekly newspapers Newswire provider targeting network affiliate broadcasters sports blog on multiple professional sports sports blog on multiple professional sports Christian television programming producer and distributor, broadcaster in three markets Magazine in and about Buffalo, NY Editor, blog aggregator, blogger Indigenous peoples music radio Sports humor blog Movie studio Film producer, cable network targeting Latina/Latinos Book publisher of self-help, inspirational books Magazine in about and Buffalo, NY Dallas/Ft. Worth market news service Television/video production company Christian television program producer and multi-channel television operator Video service for international basketball coaches, players and agents Photojournalism producer and distributor Book publisher known as founder of hip hop literature genre Video service for international basketball coaches, players and agents Sports humor blog Television network targeting gay people worldwide user generated content encyclopedia Connecticut markets weekly newspapers Video service for international basketball coaches, players and agents Traditional or Online News or Entertainment Online Online Both Online Traditional Traditional Online Both Both Entertainment Both Entertainment News News Online Online Traditional Both Both Entertainment Both Online Online Online Traditional Traditional News News Entertainment Entertainment Entertainment Entertainment Traditional Both Online Traditional Both Entertainment News News Entertainment Both Online Neither Online Traditional News Entertainment Online Neither Online Online Online Traditional Online Entertainment Entertainment Both News Neither article. The other type concerned categories of media entrepreneurs and will be published separately. DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS Analysis of interview data uncovered three clusters of phenomena related to new entry: few barriers to entry, the critical role of technological innovation, and the surprising effect of “big media” as a supporting factor—not a barrier—to entry. Media Entrepreneurs 35 The interview participants were asked to talk about what helped them get the ideas for their media businesses, and what helped in launching. They were also asked what barriers they may have encountered. If a participant could not think of any factors, they were sometimes prompted with possibilities, such as access to capital, regulation, technology, suppliers and distributors, professional background, personal connections, education and life/family situation, geographic location, and timing. Among the media entrepreneurs interviewed, a host of supporting factors was mentioned. Some cited prior experience either in business or in the media, personal connections, certain personality traits like passion and perseverance, family tradition, and having immigrant parents. Many of these factors have been well-documented in entrepreneurship research (Gartner, Shaver, Carter, & Reynolds, 2004). The skills of journalists and media producers were frequently mentioned by those with media backgrounds. Writing, photography, editing, and recording were specifically mentioned. For example, one former television anchor and news director mentioned that his journalist’s training included creative brainstorming of story ideas, and he believed this ability made it easier for him to think up ideas for new businesses. However, irrespective of backgrounds, skills, personal traits, or professional relationships, there were three consistent themes. The first theme was that most of the media entrepreneurs, even when prompted with examples, could not name barriers to entry—not financial, regulatory, structural, or technological. Industry structure (e.g., ownership concentration) and technology, far from hindering entry, were cited as sources of opportunity, and are discussed separately later. Among media entrepreneurs interviewed after the middle of 2007 when the U.S. economy weakened, only one mentioned a related concern. The second theme was that technological innovation made the media business ideas or entry feasible. In some cases, it was not just that a technology had been hitherto cost prohibitive, it was that it had not previously existed. There were seven main effects: lowered risk, attracting people who would not otherwise be entrepreneurs; reduced reliance on scarce technical expertise; access to new distribution channels; virtual organization; geographic independence; quality competition; and lowered production costs. The third theme was a sentiment that so-called “big media” was a major source of opportunity. Far from erecting barriers to entry, media entrepreneurs mentioned—some going so far as to thank—the inefficiency, the bureaucracy, and the surprising indifference or blindness of big media to new media genres, media quality, and un-served audiences and user niches. Few Perceived Barriers to Entry Whether operating in virtual or traditional realms, the entrepreneurs did not dwell on barriers. For those who mentioned barriers, they had not or were 36 B. Compaine and A. Hoag not expected to seriously impede start-up. All three book publishers among our participants cited distribution difficulties, which is well-documented in any description of publishing. However, all three tumbled to the same creative and effective solution. Two other entrepreneurs believed the too new, too innovative nature of their ideas were barriers to making sales, but seemed proud to have that problem. Two minor regulatory/legal issues came up: one videomaker had to comply with FCC rules on closed captioning, and another ran into a trademark problem; both were overcome with relatively little difficulty. In most cases, obtaining capital was not a challenge, or start-up costs were low so boot-strapping was possible. Two needed start-up funds but, upon probing, both revealed that they could have gotten financing, but did not want to share ownership control. Most simply claimed there were no barriers to entry. The interview protocol included the question, “Were there any barriers you ran into as you started up your business?” Many struggled to come up with examples: “I couldn’t call them barriers just because I was doing something I was passionate for.” “I can’t think of any major barrier right off the top of my head.” “Well, not on my end.” “As long as I don’t hear the word impossible, you know, I feel great. It’s a difficulty I can deal with.” “[The newspaper business] was very easy to get into. It was easy for advertisers to identify with and to buy into. It was something that we could replicate on a weekly basis fairly easily.” The Role of Technological Innovation There may have been a time when the cost of technology would have been seen as a barrier to many forms of media entrepreneurship: the need to have access to movie studios, printing presses, broadcasting facilities, or satellites. Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have become smaller, faster, cheaper, and less complicated to use. Rather than barriers, ICTs were viewed by the research participants as greasing entry. More than that, if ICT innovation has expanded the realm of possibilities for all media firms, big and small, it appears to give a disproportionate advantage to new entrants. The media entrepreneurs related many examples of how recent technological innovation supported entry. The examples fall into one or more of seven categories: lowered risk, attracting people who would not otherwise be entrepreneurs; reduced reliance on scarce technical expertise; access to new distribution channels; virtual organization; geographic independence; quality competition; and lowered production costs. Media Entrepreneurs 37 Above all, the Internet has made entirely new forms of media possible. For example, social media and user-generated content (UGC) have created a communication revolution. The founder of one of the best-known UGC Web sites, an encyclopedia, was in the media entrepreneur sample. Interviewed in 2006 for this project, he related how his idea for the site evolved as the Internet culture itself evolved: I had been online a lot since 1989. I was involved in a lot of email discussion groups with lots of really interesting people. At the same time I was watching the growth of the free software movement and thinking about the fact that I had all these really, really cool, smart friends online and we were all typing a lot but we weren’t actually building anything. And programmers were also making friends and doing things for fun online and they were building amazing software. And so my original thinking is, “hey, we got this tool, the Internet, which allows us to share knowledge and building things. Why don’t we do that?” That was the original concept. Lowered risk, attracting people not otherwise predisposed to entrepreneurship. Several of the media entrepreneurs spoke of getting the idea for their media businesses because of the Internet, especially Web 2.0 technologies. This perspective was especially common among a type of media entrepreneur called a missionary (Hoag & Compaine, 2007). Missionaries in this context are not conventional entrepreneurs in that they often start their companies reluctantly. They resort to entrepreneurship after trying to interest their employers or established media companies in exploiting their media ideas. Missionaries are often media industry outsiders: They have no media-related skill sets, industry knowledge, or insider connections. They know neither how media businesses work, nor how media are produced or distributed. The media are a “black box.” Therefore, they perceive starting a company as full of risk and uncertainty. The Internet, however, captured their imaginations. They could envision launching a media enterprise with the help of the Internet because it seemed so accessible. These people might never have thought of becoming media entrepreneurs, but perceived that one can do anything, reach anyone, on the Internet; and, the risk is lower because the potential for financial loss is mitigated by the economics of the Internet, as compared to starting a media company—a newspaper, for example—requiring considerably less start-up capital (Compaine & Gomery, 2000). Lowered reliance on technical expertise. A few spoke of the diminished need for technical expertise because ICTs enable people with less sophisticated skills—the entrepreneurs themselves—to produce, market, and distribute. They found it easier to start their media businesses because they did not have to search for and pay technicians and professional producers. 38 B. Compaine and A. Hoag Typical of this kind of talk about ICTs, a video producer said, “The software was $100 and I bought the web site domains and I had free hosting and did all the web development myself so all I had to pay for really was getting the DVDs duplicated.” Distribution. One of the most frequently cited advantages from recent ICT development was the creation of new distribution channels. The Internet is the new distribution channel. Media products and services can be digitized and, therefore, can be distributed as bits via the Internet. For example, one research participant, a satellite television operator with a lineup of mainstream and Christian television networks, learned that the leased satellite transponders would soon burn out. The cost of leasing new transponders was high. The operator told of reading about Internet Protocol Television (IPTV)—an alternative distribution channel on the Internet. He appears to have been the first multichannel television operator (e.g., cable systems and satellite TV companies) to adopt that relatively new and unproven technology. He re-launched his service in late 2007, and reported success. Likewise, many other media entrepreneurs spoke of the relative ease of reaching audiences, readers, subscribers, and users via the Internet. Comments from a start-up television network owner and a magazine publisher, respectively, on using the Internet to reach audiences exemplify the idea: “So I didn’t care if I had 3,000 people coming to my site. That’s 3,000. They are watching it and experiencing it like television.” “Now I can reach 12,000 people a day just by creating something that I find is kind of artistic.” The Internet was not a universal solution to distribution bottlenecks. As mentioned earlier, there were three book publishers, one feature filmmaker, and one television programming producer in the sample. Downstream customer-facing segments, book stores, movie theatres, television stations, and cable operators have long been characterized by closed and inflexible distribution systems. None of these entrepreneurs could bypass those networks, but almost no one mentioned it as a problem—all were able to access traditional channels. Virtual organization. Still others spoke of ICTs making it feasible to operate virtual organizations. Thanks to the Internet and a range of applications, it is easy to outsource and partner for the short term, rather than enter into long-term contracts or take on permanent employees. Several entrepreneurs in the news sector spoke of the ease of finding reporters and news producers online and acquiring content that way. The concept of freelancers and stringers is nothing new, but the Internet made it fast Media Entrepreneurs 39 and easy to find high-quality journalists. Exemplifying the idea of the virtual organization, one interviewee put it this way: We’re on the cutting edge of what I would call highly participatory enterprise . . . in that [name of media enterprise]; we have only three employees. . . . I think that’s pretty unique to have such a huge public impact with such a small number of paid employees. Geographic independence. When firms are virtual, geography matters less. Entrepreneurs spoke of living and working in low-cost areas and still enjoying easy access to customers and suppliers. For example, when a producer of children’s animation needed music for his videos, he searched the Internet, found a suitable composer in another city, and collaborated by sharing files. Advertising sales for an Altoona, PA-based television news entrepreneur are managed by the co-owner in Charlotte, NC. One book publisher lives and runs her business in a rural area of Wisconsin. She manages relationships with authors, distributors, and retailers virtually. A Los Angeles-based TV network founder uses a Web designer in New York. One interview participant’s feature-length film was considered a box office phenomenon in Variety and Hollywood Reporter, earning more than $33 million in 2008. Even so, he can run his studio in Albany, GA—far away from the traditional media capitals—because he can manage relationships electronically with a music label in Nashville and with the major Hollywood movie studio that distributes and markets his film. As such, he could produce the film with a $500,000 budget. The mean cost of a Hollywood feature, as mentioned earlier, was nearly $66 million in 2006. Quality competition. Self-published books, independently produced films and music, and low-budget magazines have found success since the genres were first introduced. However, their ability to compete on quality alongside big producers with deep pockets is new. “Production values” refers to the look and feel of a media product. Advances in production tools have greatly improved small media makers’ abilities to achieve high production values rivaling major Hollywood studios, chain newspapers, and major music labels. Two new entrants into animation and photojournalism, respectively, explained it this way: Now we’re in a time where simultaneously the tools for [the Internet] and video are cheap enough to where I can not only get a video camera . . . but I can edit it real easy on my computer and I could put it up online . . . the thing that really sets the production apart in the world in the traditional media is production quality . . . and so I could compete production quality-wise. 40 B. Compaine and A. Hoag We want our brand to be considered a top tier media brand even though we’re, you know, small. . . . We have a big impact out there right now. People know about us. Lowered production costs. ICT innovation has greatly reduced production costs primarily because the tools have become so cheap. Nearly all our entrepreneurs, whether in a traditional sector or online, mentioned this. The newspaper entrepreneurs, for example, cited advances in computerized layouts as significantly reducing production costs. A television network operator told of acquiring pre-produced programming cheaply because the Internet made it easy to find and make deals with television companies in other countries, who would not otherwise have had access to the U.S. market. Entrepreneurs in the video space cited cheaper production inputs. One described it this way: The democracy of the production tool set. I mean we have $5,000 Macintosh’s that rival the $250,000 AVID system we were using at MSNBC. It used to be $70,000 to get an HD camera. Now I own one; it’s $5,000. You know democracy of production that happened is really remarkable. We don’t own a printing press, right? We have 100 different countries that hit our web site every month. In sum, nearly all of the 30 entrepreneurs talked about recent innovations in ICTs making it easier to start their media companies in at least one of seven different ways. In some cases, it was the Internet that made new enterprise possible at all. Most significantly, perhaps, many of the entrepreneurs believed that ICT innovation now makes their product quality and availability indistinguishable from their much bigger competitors. BIG MEDIA: BARRIER OR SOURCES OF OPPORTUNITY? One of the principal justifications for this study was the need to understand how ownership concentration, vertical and horizontal integration, and conglomeration impede new entry, if at all. For these entrepreneurs—most of whom are directly competing with big media corporations—dominant firm conduct never created barriers. In talking about what helped them get their ideas or in starting up, quite unexpectedly, several media entrepreneurs spoke of industry structure as their main source of inspiration. Even for those who got their ideas another way, the view that so-called “big media” often fails to meet the market prevailed. Innovation, to many, seemed incompatible with these legacy media companies. Typical sentiments were as follows: Media Entrepreneurs ● ● ● ● 41 “Time Warner, big businesses, are still scrambling to try to get their bearings and get a grip on the market.” “Just been real beneficial for us and real typical for big s∗∗ ts in the industry that can’t move so quick.” “I think the traditional media companies really have to wake up to the possibilities here.” “I want to be it before MTV can start a channel. Before you know BET can start another channel. . . . I don’t have to go through a ton of bureaucracy and red tape and focus groups and things like that. And by the time maybe some bigger media conglomerates do all their homework, I want to already be on the air.” A couple of media entrepreneurs had left jobs at a big media corporation after unsuccessfully trying to get their employers to use their ideas. They expressed belief that big media companies are unable to take risks, be innovative, act quickly, or even to see obvious opportunities: “It’s simply not that hard to create a good financial structure for photojournalism. And we had that. We had that at Corbis and they decimated it. So that bums me out.” “[T]hose people are going to get so upset about being at the big corporate place that doesn’t care about what they care about.” Some interview participants noted that their chosen market was wide open because media conglomerates either did not recognize or did not care to exploit opportunities: “[Publishing books for girls is] not a decision that you would make in corporate America.” Then others mentioned that directly competing with a big media corporation was possible because the products were of poor or declining quality: ● ● ● “[There was] the kind of deterioration of the news product that was in town at the time. It had recently been bought by a large corporation.” “It seemed there was a dearth of coverage as far as local community activism. There was not a lot of coverage of positive events happening in the city . . . the bigger news organizations tend to really sensationalize just about anything you wouldn’t want to hear about.” “[I]n our market the local paper that was currently serving it was doing a very poor job. And they were owned and they still are owned by a large newspaper chain, the Journal Register Company. And they are not known 42 ● B. Compaine and A. Hoag in the industry for being a very high quality newspaper. So what they had done was bought this newspaper group and then the quality of editorial went down. And that’s when we just started getting active in this whole idea so we saw there was an opportunity.” “The Buffalo News just doesn’t get it. [It is] just kind of widely considered part of the problem in Buffalo.” Despite popular and scholarly assumptions that barriers exist ex ante in oligopolistic media markets, the current market structure may actually encourage new entry. Although utterly consistent with Schumpeter’s (1942/1976) predictions that market power is fleeting, this was the biggest surprise in this 4-year study; it was a consistent message from media entrepreneurs that so-called “big media,” far from impeding entry, are a principal source of opportunity. An oligopolistic media industry structure erecting barriers to new entrants was not the experience of most of the entrepreneurs. In sum, long interviews with 30 media entrepreneurs produced an enormous volume of data. The texts pointed to a positive outlook for media entrepreneurship because entry is possible, and sometimes even easy. Three patterns bubbled up from interviews concerning factors and conditions that provide a hospitable environment for entry into media markets: few perceived barriers to entry, the seven positive effects of technological innovation, and the conduct of dominant media firms that encourage new competition. DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION A Hospitable Environment Promoting New Entry As described at the outset, our objective for this study was exploratory: What were the circumstances under which people get the idea for new media products or services and then, further, act on those ideas by starting an enterprise. In general, a host of factors positively and negatively influence new entry in any market. In media, however, the data gleaned from our structured surveys uncovered that sources of support and opportunity are abundant, and there are few perceived barriers to entry, according to the entrepreneurs interviewed. The experiences related by the 30 media entrepreneurs paint a picture of a hospitable environment for starting a business. Figure 1 depicts the combination of the three documented conditions that positively influence new entry. In the case of the media industry, ICT innovation is part of the overall model of a hospitable environment. Media entrepreneurs perceived few, if any, barriers to entry, and the presence of so-called “big media” actually creates opportunity. 43 Media Entrepreneurs Few barriers to entry ICT Innovation Opportunity Created by Big Media Lower risk attracts nonentrepreneurs Less reliance on technical expertise Quality Competition Alternative Distribution Channels Virtual Organization Geographic Independence Lower Production Costs FIGURE 1 Conditions Creating Hospitable Environment for New Entry (color figure available online). The current business environment and media industry market structure in the United States, the expanding demand for media products, and the many ways in which ICT innovation supports new entry all conspire to create potentially excellent prospects for new entrants. The elements of uncertainty and risk, as well as capital barriers to entry, have been counterbalanced by the lower costs of many new media enterprises and, therefore, less need for outside capital and less of a risk to both outside investors and the entrepreneurs themselves. This applies to both new media as well as traditional media. For example, no longer is a license for spectrum needed to provide audio or video programming, as it can be successfully streamed or downloaded to computers and portable devices. Traditional media products, such as newspapers or books, may also be produced and distributed without the need to buy printing presses or employ limited physical distribution channels. Technology and economics have conspired to undercut many of the barriers that had existed to would-be media entrepreneurs. Indeed, this research suggests no problems that public policy could fix. Future Research The qualitative methods effectively illuminated the main research question. However, qualitative studies are designed to discover phenomena and build theory; they are not intended to deliver generalizable findings. This is an early study on media market entry in the 21st century. Its focus on factors that support and hinder new entry appears to be a rich area for further research. As such, we are not ready to fit our findings into existing theory or to propose new theory. A logical next step might be, again in a qualitative vein, to delve into emerging niches and the business models associated with them. 44 B. Compaine and A. Hoag For example, several sports media and Christian media entrepreneurs were recruited because potentially innovative business models were observed in the initial sample. Niches like these offer controls to isolate and observe rapid change in Internet and traditional media business models. Traditional media business models based solely on advertising sales may be on the decline. For example, in 1998, the broadcast television share of ad spending in the United States was nearly $30 billion, whereas cable television attracted < $10 billion. By 2008, broadcasting revenues had stagnated, whereas cable’s share more than doubled (Television Advertising Bureau, 2010). In turn, cable television is starting to lose ground to IPTV, meaning its advertising sales model is also now threatened. The continuous emergence, rapid rise, and potential fall of these new media suggest unusually high entry, exit, and, therefore, turbulence. Web 2.0 technologies will continue to improve, and penetration rates for broadband will continue to grow. Globalization of the media in the Internet age is practically automatic. At the same time, some traditional media, newspapers most dramatically, are in decline. Schumpeter (1942/1976) would agree; the current situation qualifies as a true wave of creative destruction. This study investigated the factors that support and hinder new entrants in U.S. media markets. However, the variables culled from the interviews suggest opportunities for testing their application to entrepreneurial activity in other industry sections. They included: ● ● ● ● ● ● Lower risk, which may attract those who may have foregone entrepreneurial activity because of its perceived higher risk. Less need for technical expertise, as information technologies have lowered the skills needed for many activities, from graphic design to database creation. Alterative distribution channels, primarily via the Internet, which may be used for marketing and communications. The option of virtual organizations. This expands the universe of potential colleagues and reduces transaction costs associated with employment. Geographic independence, another piece of the virtual organization. Live here, do business there. No need to uproot oneself or family for many types of opportunities. Lower production costs. There are many ways to examine this, from the digital media to easier access to the global supply chain. Intuitively, these conditions would seem to make sense as being widely appreciated by today’s entrepreneurs. Further research would be a helpful next step to confirm the widespread applicability of these conditions. Media Entrepreneurs 45 REFERENCES Achtenhagen, L., & Raviola, E. (2009). Balancing tensions during convergence: Duality management in a newspaper company. International Journal on Media Management, 11, 32–41. Acs, Z., & Audretsch, D. (Eds.). (2003). Handbook of entrepreneurship research. New York: Springer. Anderson, C. (2009). Free: The future of a radical price. New York: Hyperion. Bagdikian, B. H. (2004). The new media monopoly. Boston: Beacon. Baker, C. E. (2007). Media concentration and democracy: Why ownership matters. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. Bakker, P. (2002). Free daily newspapers—Business models and strategies. International Journal on Media Management, 4, 180–187. Baumol, W. J. (1993). Entrepreneurship, management and the structure of payoffs. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory. London: Sage. Compaine, B. (Ed.). (1979). Who owns the media? Concentration of ownership in the mass communications industry. White Plains, NY: Knowledge Industry Publications. Compaine, B. (2005). The media monopoly myth: How new competition has expanded Americans’ sources of information and entertainment. Washington, DC: New Millennium Research Council. Compaine, B., & Gomery, D. (2000). Who owns the media? Competition and concentration in the mass media industry. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Federal Communications Commission. (2009). Annual assessment of the status of competition in the market for the delivery of video programming, 13th annual report. Washington, DC: Author. Available at: http://www.fcc.gov/ Document_Indexes/Media/2009_index_MB_Report.html Fiet, J. (1996). The informational basis of entrepreneurial discovery. Small Business Economics, 8, 419–430. Franke, N., & Schreiner, M. (2002). Entrepreneurial opportunities with toolkits for user innovation and design. International Journal on Media Management, 4, 225–234. Gartner, W. B., Shaver, K. G., Carter, N. M., & Reynolds, P. D. (Eds.). (2004). Handbook of entrepreneurial dynamics. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Geissler, U., & Einwiller, S. (2001). A typology of entrepreneurial communicators: Findings from an empirical study in e-business. International Journal on Media Management, 3, 154–160. Guba, E. G., & Lincoln, Y. S. (1998). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The landscape of qualitative research (pp. 195–220). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hang, M., & van Weezel, A. (2007). Media and entrepreneurship: What do we know and here should we go? Journal of Media Business Studies, 3, 51–70. Hoag, A. (2008). Measuring media entrepreneurship. International Journal on Media Management, 10, 74–80. 46 B. Compaine and A. Hoag Hoag, A., & Compaine, B. (2007, August). Media entrepreneurship: Missionaries and merchants. Paper presented at the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communications, Chicago, IL. Huang, J. S., & Heider, D. (2007). Media convergence: A case study of a cable news station. International Journal on Media Management, 9, 105–115. Huberman, A. M., & Miles, M. B. (1998). Data management and analysis methods. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (pp. 179–210). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. James, M. (2009, May 4). TV networks are uneasy about declining advertising. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2012 from http://articles.latimes.com/ 2009/may/04/business/fi-ct-cbs4 Kihlstrom, R. E., & Laffont, J. J. (1979). A general equilibrium theory of firm foundations based on risk aversion. Journal of Political Economy, 87, 719–748. Knight, F. (1921). Risk, uncertainty and profit. New York: Houghton Mifflin. Liebling, A. J. (1961). The Press. New York: Ballantine. McChesney, R. W. (2008). The political economy of media: Enduring issues, emerging dilemmas. New York: Monthly Review Press. McVea, J. F. (2009). A field study of entrepreneurial decision-making and moral imagination. Journal of Business Venturing, 24, 491–504. Mohr, I. (2007). Box office, admissions rise in 2006. New York: Variety. Retrieved January 15, 2010, from http://www.variety.com/article/VR1117960597. html?categoryid=1236&cs=1&query=lor+of+the+rings&query=average+cost+ of+movie Noam, E. (2009). Media ownership and concentration in America. New York: Oxford University Press. Reisman, D. (2004). Schumpeter’s market: Enterprise and evolution. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Rentería, M. (2007). Media concentration in the Hispanic market: A case study of TV Azteca vs. Televisa. International Journal on Media Management, 9, 70–76. Sarasvathy, S., Dew, N., Velamuri, S. R., & Venkataraman, S. (2003). Three views of entrepreneurial activity. In Z. Acs & D. Audretsch (Eds.), Handbook of entrepreneurship research. New York: Springer. Schumpeter, J.A. (1976). Capitalism, socialism and democracy (3rd ed.). London: Allen & Unwin. (Original work published 1942) Stolper, W. F. (1994). Joseph Alois Schumpeter: The public life of a private man. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Te Velde, R. (2004). Schumpeter’s theory of economic development revisited. In T. E. Brown & J. Ulijn (Eds.), Innovation, entrepreneurship and culture: The interaction between technology, progress and economic growth (pp. 103–129). Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Tyson, J. (2000). How movie distribution works. Atlanta, GA: HowStuffWorks.com. Retrieved January 15, 2010, from http://www.howstuffworks.com/moviedistribution.htm Media Entrepreneurs 47 U.S. Economic Census (2007). American Fact Finder. Retrieved February 4, 2012, from http://bit.ly/zy0AFS Vaghely, I. P., & Julien, P.-A. (2010). Are opportunities recognized or constructed: An information perspective on entrepreneurial opportunity recognition. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 73–86. Van Kranenburg, H., & Hogenbirk, A. (2006). Issues in market structure. In A. B. Albarran, S. M. Chan-Olmsted, & M. O. Wirth (Eds.), Handbook of media management and economics (pp. 325–344). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Vogel, H. L. (2007). Entertainment industry economics (7th ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. APPENDIX Media Entrepreneur Interview Protocol 1. First, could you tell me a bit about yourself? (PROMPT IF NECESSARY FOR BACKGROUND, AGE, FAMILY, immigrant, family tradition of e-ship, STAGE OF LIFE, ETC.) 2. [IF DOESN’T ALREADY HAVE A FIRM PROFILE FROM WEBSITE OR ARTICLE]. We’d like to have a short profile of your current venture ____________. Is there a website or do you have a brochure or description we could get? For this next set of questions, think about how you came up with the idea for your current venture, ___________. 3. How did the idea for starting your business develop? 4. Which came first to you, the idea or your decision to start some kind of business? IF “DECISION,” SKIP TO 6. 5. If you were looking for an appropriate idea for a business, about how many were considered before selecting this idea? 6. Has the idea or opportunity changed very much since the beginning or is it pretty much the original concept? 7. Why did you think it was a good idea for a media enterprise? 8. What led to your idea? [PROMPT IF NECESSARY, BUT MAKE SURE SUBJECT CONSIDERS ALL THE FOLLOWING] a. It developed from another idea I was considering. b. My experience in business. c. My experience in the media. d. Thinking about solving a particular problem. e. Discussion with my friends and family f. Discussions with potential or existing customers g. Discussion with existing suppliers or distributors h. Discussion with potential or existing investors/lenders? i. Knowledge or expertise in the media? j. Can you think of anything else that led to your business idea? 48 B. Compaine and A. Hoag 9. Did geography or location make a difference in helping you come up with your idea? IN other words, did it matter where you lived or frequently traveled to get your idea? Now, for this next set of questions, think about how and when you decided to act on your idea, to actually start the venture,_____________. 10. How did timing play a role? a. Did you start your business right away or did you wait to act on your idea? Why? b. Why did you think it was a good time to capitalize on your idea? c. Would it have worked out just as well if you had waited a year? Two years? Five years? Why or why not? 11. When you decided to act on your idea, were you employed? [IF YES, CONTINUE. IF NO, SKIP TO NEXT CLUSTER OF QUESTIONS.] a. Why didn’t you try to get your organization to capitalize on the idea? Or why didn’t you try to sell or give your idea to another organization? b. Why did you decide to start the business independently? 12. [IF NO TO Q.11] Why did you decide to start the enterprise independently? Why not take it to a company that already was in a related business? 13. Were there any barriers that you ran into as you started up your business? [PROMPT IN PARTICULAR FOR FINANCIAL BARRIERS, REGULATORY BARRIERS, TECHNOLOGY BARRIERS] 14. Was there anything in your experience or background that helped you start your business? [PROMPT IF NECESSARY, BUT MAKE SURE SUBJECT CONSIDERS ALL THE FOLLOWING] a. Did you possess any special knowledge or information? b. Traits or talents? c. Skills? d. Prior experience in business? e. Prior experience in the media? f. Relationships or connections with potential or existing customers g. Connections with suppliers or distributors? h. Connections to financing – investors or lenders? i. Did you own or have access to any special facilities, equipment or technology? 15. Did you invest your own money in the idea? About what proportion of the total investment needed to get the business going came from you? (If applicable, ask: and from your partner?) 16. Was this your first business? Was it your first media business? 17. What has been the most rewarding part of your media venture? 18. What has been the most disappointing or frustrating part? 19. Now I have some general questions about media start-ups. Which of these statements best captures your motivation in starting this venture: a) What most interests me is running a business. b) What most interests me is Media Entrepreneurs 20. 21. 22. 23. 49 running a “media” business, (If b, then: What do you think is different about a media business from other product and service businesses? Have you had other ideas for media businesses or products that you did not act on or that proved too difficult to start up into a business? If so, can you tell me about them [FIND OUT WHY NOT EXPLOITED.] Finally, I have some questions about you. How do you measure success? What keeps you going on bad days? Your reactions to some specific statements about business start-ups would also be very useful. How would you respond to the following descriptions of the firm and its situation? Would you tend to agree or disagree with each of the following statements? a. “I have engaged in a deliberate, systematic search for an idea for a new business” b. “The best business ideas just come, without a need to search for them.” c. “For me, identifying business opportunities has involved several learning steps over time, rather than a one-time thing”