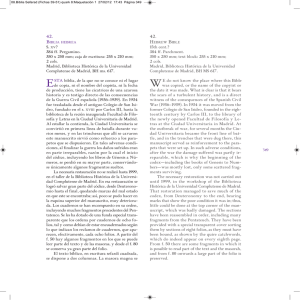

Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad* The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction* David Stern Universidad de Pensilvania, Filadelfia University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia L T * Este ensayo es una versión simplificada de otro más extenso, y con un mayor número de notas, que aparecerá en 2012 (Stern en prensa). Aquí las notas se han reducido al mínimo con el objeto de hacer el texto accesible al lector no especialista. Quien esté interesado podrá encontrar en la versión larga referencias a las fuentes primarias y a la literatura especializada sobre los temas que aquí se abordan. * This essay draws upon a much lengthier and heavily oS libros hebreos que los judíos de Sefarad produjeron durante la Edad Media constituyen uno de los logros culturales más importantes de la historia judía. A partir del s. xII, y es posible que incluso antes, los judíos de la Península Ibérica copiaron, decoraron e iluminaron manuscritos hebreos de todo tipo (obras legales, libros de oración destinados al uso litúrgico, de poesía y belles-lettres, filosofía, homilética, e incluso ciencia). La mayor parte de estas obras se redactaron originariamente HE Hebrew books produced by Sephardic Jewry in the Middle Ages constitute one of the great cultural achievements in Jewish history. From the late twelfth century on, and probably even earlier, Iberian Jews wrote, decorated, and illuminated Hebrew manuscripts of all kinds—legal works, prayer and other liturgical books, poetry and belles-lettres, philosophical, homiletical, even scientific works. Most of these works were originally composed in Hebrew, but many others were written in Judaeo- annotated article which will be published in 2012 (Stern forthcoming). In order to keep this essay accessible to a lay audience, I have limited the number of endnotes. Readers interested in primary sources and scholarship on all the issues raised in the present essay should consult the longer study. 49 50 en hebreo, pero muchas otras fueron escritas en judeo-árabe, y algunas traducidas del árabe o del latín. Muchas de ellas fueron además decoradas e ilustradas, en ocasiones magníficamente. Tradicionalmente, dos géneros han destacado por su excepcionalidad en el extraordinario conjunto de libros producidos en la Península Ibérica: la Biblia hebrea y la Haggadah. Las haggadot sefardíes se han estudiado en detalle, y han formado parte de muchas exposiciones. Frente a esas exposiciones, la que aquí nos ocupa se centra en la Biblia y obras auxiliares a su lectura y estudio: comentarios bíblicos, gramáticas del hebreo bíblico, y otras obras de tipo parafrástico. En este ensayo me propongo esbozar las líneas fundamentales de la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad, desarrollando algún aspecto de carácter más general relacionado con ella. En la Edad Media, la Biblia he1 En hebreo brea adoptó en la cultura judía dos medieval y formatos distintos: el de rollo y el de moderno, la palabra códice, en cada caso resultado de una sefer significa libro. larga trayectoria. Empezaremos por En la Biblia, sin embargo, el primero de ellos, el Sefer Torah 1 la palabra connota (pl. Sifre Torah, rollo de la Torah) . Se podría decir que el Sefer cualquier tipo de comunicación Torah es el formato más tradicioescrita, y se usa nal de libro en la historia de la culcon frecuencia tura occidental. En la Antigüedad, para designar rollos, el formato de libro más común un uso que era el rollo, que era de papiro y, en se mantiene en la actualidad por ocasiones, de piel. La forma matelo que respecta al rial del rollo fue uno de los logros rollo de la Torah. del mundo antiguo, y tras el Sefer Torah tal y como lo conocemos hoy (un rollo único de gran formato) hay una larga historia de estabilización textual y evolución de la técnica de escritura. Esa historia incluye la transición del papiro a la piel, y de esta al pergamino, el desarrollo de las técnicas de tinte y cosido, la David Stern Arabic, and some were translated from Arabic or Latin. And many of these books were decorated and illustrated, some fabulously. Among all the extraordinary books produced in the Iberian Peninsula, two genres have traditionally been recognized as truly exceptional: the Hebrew Bible and the Haggadah. Sephardic haggadot have extensively been studied and frequently displayed in exhibitions. The present exhibition is devoted to the Bible and its ancillary compositions— Bible commentaries, grammars of biblical Hebrew, and other paraphrastic works. In the present essay, I will sketch out the main contours of the history of the Hebrew Bible in Sepharad and discuss some of the larger issues connected to its history. By the Middle Ages, the Hebrew Bible existed in Jewish culture in two distinct material forms: as a scroll and as a codex, each of which has its own lengthy history. We will begin with the Sefer 1 In medieval and Torah (pl. Sifre Torah, Torah scroll).1 modern Hebrew, The Sefer Torah is, arguably, the the word sefer single most traditional book-form connotes a book. in the history of Western culture. In the Bible, In antiquity, the most common however, it book-form was that of the scroll, originally usually written on papyrus or, connotes any sometimes, leather. Its form goes type of written communication back to some of the earliest reachand is typically es of the ancient world, and behind used to designate the Sefer Torah as we know it to- scrolls, a usage day—a single monumental scroll— which continues lies a lengthy history of textual sta- to be used even bilization and scribal technology. today in respect to This history includes the transi- the Torah scroll. tion from papyrus to leather to parchment, the development of modes of tanning; sewing; the history of Hebrew script, and the development of the scribal conventions that evolución de la grafía hebrea y el desarrollo de las convenciones escriturarias que determinan la manera en la que se ha de escribir el texto del Pentateuco. En el mundo antiguo, donde la mayor parte de los rollos eran de una longitud relativamente moderada, el Sefer Torah se componía en origen de cinco rollos, uno por libro, denominados ḥomashim (sing. ḥomesh). El rollo único, de gran formato, que incluye todo el Pentateuco, tal y como lo conocemos hoy, solo aparece a finales del periodo rabínico clásico. En esa época la producción del Sefer Torah estaba ya sujeta, de acuerdo con la halakhah (ley rabínica), a una serie de exigencias legales, virtualmente rituales. De ese modo, y según dictaba la normativa, el Sefer Torah debía ir escrito en letra cuadrada asiria usando una tinta especial sobre cierto tipo de pergamino, cosido con determinados tipos de hilo, con un número específico de líneas por columna, dejando determinados espacios entre las secciones, y disponiendo ciertos pasajes de manera especial. Ni siquiera los rabinos del periodo clásico llegaron a ponerse completamente de acuerdo sobre esta normativa, de modo que en los distintos centros judíos de la Edad Media se fueron desarrollando, con diferencias mínimas, distintas tradiciones textuales y escriturarias para la producción de los Sifre Torah. En la lám. 1 se puede observar un Sefer Torah copiado en Calahorra o en Tudela en los ss. xIv o xv, escrito en la típica grafía sefardí cuadrada. Los Sifre Torah y los códices bíblicos sefardíes se distinguían por su exactitud, fruto esta de la destreza de los copistas judíos sefardíes y de la predilección que la cultura judía de la Península Ibérica había tenido siempre por el hebreo bíblico, como pone de manifiesto la tradición lingüística y filológica que se remonta a figuras como Judá Ḥayyūŷ y Yonah ibn Ŷanāḥ, a finales del s. x y a lo largo del s. xI (Sarna 1971, 329–331 y 345–346). Fuentes determine how the text of the Pentateuch is to be written. In the ancient world, most scrolls were of relatively moderate length, and a complete Sefer Torah was originally five separate scrolls, called ḥomashim (sing. ḥomesh), one per biblical book. only by the end of the classical rabbinic period had the single monumental scroll containing the entire Pentateuch come into existence, and by this time the production of the Sefer Torah was governed according to halakhah (rabbinic law) by detailed legal, virtually ritualistic requirements. Thus, a “kosher” Torah scroll had to be written in square Assyrian letters in a special type of ink on a certain type of parchment, sewn together with particular types of threads, with a certain number of lines per column, with prescribed spaces between sections, and with certain passages laid out in special formats. There was never complete agreement even among rabbinic sages on these various requirements, and there eventually developed different—albeit usually minor—textual and scribal traditions for writing Sifre Torah in different Jewish centers in the Middle Ages. Fig. 1 pictures a Sefer Torah, written either in Calahorra or Tudela in the fourteenth or fifteenth century; the text is written in a typical Sephardic square script. Sephardic Sifre Torah and Bible codices were especially famous for their accuracy, both because Sephardic scribes were especially known for their skill as copyists as well as on account of a native proclivity in Iberian Jewish culture for biblical Hebrew as evidenced in the linguistic and philological studies going back to such figures as Judah Ḥayyūj and Jonah ibn Janāḥ in the late tenth and early eleventh centuries (Sarna 1971, 329‒331, 345‒346). Tenthcentury sources already refer to the “accurate and ancient Sephardic and Tiberian Bibles,” Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 51 52 Lám. 1 / Fig. 1. Sefer Torah, fragmento. Sefer Torah, fragment. Calahorra, Archivo catedralicio y diocesano de Calahorra y La Calzada, S/Sign. © Archivo catedralicio y diocesano de Calahorra y La Calzada. 53 54 del s. x hacen ya referencia a «las antiguas y muy correctas biblias de Sefarad y Tiberias» (Stern 1870) 2 cuya excelencia llega a re2 Así aparecen conocerse incluso en Ashkenaz. en N. Sarna, «Introductory Así, Meir de Rothenberg (finales Remarks» en del s. xIII) menciona «la superioriHaggahot dad y exactitud de los libros de SeMaimuniyyot farad», y a finales del s. xIII el talmu[Glosas a dista Menaḥem ben Salomón Meiri Maimónides] (Perpiñán, 1249–1316) menciona a (Mishneh Torah 8, un rabino alemán que se dirigía a ToHikhot Sefer ledo para adquirir allí un códice del Torah 2, 4). Pentateuco copiado de un rollo de la Torah escrito por el famoso Meir ha-Levi Abulafia en Toledo para usar ese códice sefardí como modelo a la hora de escribir Sifre Torah en Ashkenaz (!) (Hirschler 1996, 48). En la Edad Media, el Sefer Torah había pasado ya a ser, ante todo, un artefacto litúrgico, usado para leer en voz alta el texto bíblico y cantarlo en público en la sinagoga a lo largo de un ciclo anual de lecturas semanales. No era este un libro en el sentido ordinario del término. En cuanto que rollo ritual, estaba sujeto a una serie de normas que no solo gobernaban su producción, sino también su uso y manipulación, como si de un algún tipo de sanctum, u objeto sagrado, se tratase. Se desconoce cuántos Sifre Torah existieron, o cuántas comunidades judías disponían de uno propio. Un rollo de la Torah de gran formato era un objeto extraordinariamente caro. A partir de un responsum de Maimónides (Moisés ben Maimón, 1135-1204) y de otras fuentes, sabemos que no todas las comunidades se podían permitir el tener su propia Torah; en situaciones así, Maimónides llegó a permitir que las comunidades judías leyesen la Torah en códices en la sinagoga. En un caso u otro, es obvio que el Sefer Torah no era una biblia que los judíos leyeran a diario, o que estudiasen, o que David Stern (Stern 1870) 2 and their excellence was recognized even in Ashkenaz by such figures as Meir of Rothenberg (end of thirteenth 2 Haggahot century) who mentions “the supe- Maimuniyyot rior and exact books of Sepharad.” [Maimonidean Another thirteenth-century Tal- Glosses] (Mishneh mudist, Menaḥem ben Solomon Torah 8, Hilkhot Meiri (Perpignan, 1249‒1316), de- Sefer Torah 2, 4), scribes a German rabbi who jour- as cited by neyed to Toledo to acquire a N. Sarna in his “Introductory codex of the Pentateuch that was Remarks.” copied from a Torah scroll written by the Sephardic sage Meir Ha-Levi Abulafia in Toledo so as to use the Sephardic codex to write Sifre Torah in Ashkenaz (!) (Hirschler 1996, 48). By the Middle Ages, the Sefer Torah had become primarily a liturgical artifact that was read aloud and chanted publicly in the synagogue in an annual cycle of weekly readings; it was not a book in any ordinary sense of the term. As a ritual scroll, particular laws governed not only its production but also its usage and handling, almost as though it were a kind of sanctum, a holy object. How many Sifre Torah actually existed and how many Jewish communities owned their own Sefer Torah is not known. A monumental Torah scroll was an exceedingly expensive item, and we know from one responsum of Maimonides (Moses ben Maimon, 1135‒1204) and other sources that not all communities could afford to own their own Torah; Maimonides even permitted such communities to read the Torah in the synagogue from a codex. In any case, the Sefer Torah was clearly not the Bible that Jews read on a daily basis or studied or owned individually except, perhaps, for some extremely wealthy persons or sages who managed to write their own personal copies. The Bible that Jews un individuo (salvo quizás alguna persona muy adinerada, o algún erudito que fuese capaz de escribir de su puño y letra una copia) pudiera poseer. La Biblia que los judíos poseían, la que leían y en la que estudiaban, era un códice, el formato bíblico que hoy denominamos «libro». El códice, es decir, el formato libro, se introdujo relativamente tarde en la cultura literaria judía. Como ya se ha observado, el formato de libro más común en occidente durante la Antigüedad fue el rollo. El códice apareció por primera vez en la cultura occidental en torno al cambio de era, y hacia principios el s. v casi todos (salvo los judíos, que continuaban escribiendo sus obras literarias en rollos) lo habían adoptado como formato predilecto en sustitución del rollo. Los judíos, por su parte, no comenzaron a adoptar el formato códice hasta los ss. vII–vIII. Los códices judíos más antiguos que se conservan datan de finales del s. Ix y comienzos del s. x, y proceden en su totalidad de oriente Medio y el Norte de África. Prácticamente todos ellos son biblias, en las que el texto hebreo, vocalizado y acentuado, a tres columnas, va acompañado de masora3. En estos códices (lám. 2) 3 Sobre los primeros la masora aparece escrita de dos forcódices masoréticos, mas en los márgenes de la página: véase Stern 2008. la masorah qetanah (masora parva) se recoge fundamentalmente en forma de abreviaturas en los márgenes externos y en los que separan las columnas internas. La masorah gedolah (masora magna), que desarrolla el contenido de la masorah qetanah, aparece en dos o tres líneas en los márgenes superior e inferior de la página. En algunos casos la masorah gedolah está escrita en forma de dibujos florares o arquitectónicos realizados en micrografía, o escritura diminuta (lám. 3), un tipo de diseño verbal que parece ser exclusivo del arte judío. El fuerte impacto del libro islámico, y sobre todo del Corán, se pone en owned, read from, and studied was a codex, the Bible in the form of what we today call a book. The codex or book-form was a relative latecomer to Jewish literary culture. As noted earlier, the most common type of book-form in antiquity in the West was the scroll. The codex first appeared in Western culture around the turn of the common era and had largely replaced the scroll as the preferred book form by the beginning of the fifth century—that is, among nearly everyone, except Jews, who continued to write their literary texts in scrolls. It was probably not until the seventh or eighth centuries that Jews began to take up the codex form. The earliest surviving Jewish codices date from the late ninth and early tenth centuries, all of them from the Near East or North Africa. virtually all these codices are Bibles with the vocalized and accentuated Hebrew text written in three columns on each folio page, and with the masorah.3 In these codices (Fig. 3 on the early 2), the masorah is written in the masoretic codices, margins of the page in two forms— see Stern 2008. the masorah qetanah (masora parva) appears largely in the form of abbreviations on the outer side and inter-column margins; and the masorah gedolah (masora magna), an expansion of the masorah qetanah, in two or three lines across the width of the page on the upper and lower margins. In some cases, the masorah gedolah is written in geometric or floral or architectural patterns in micrography, miniature writing (Fig. 3), a type of verbal design that seems to be unique to Jewish art. on both these text pages and the so-called carpet pages at the beginning and end of some codices—brilliantly painted pages covered with intricate ornamental designs that resemble those found on oriental carpets (hence their name) and that replicate Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 55 56 Lám. 2 / Fig. 2. Códice de Alepo, Alepo, 930. Aleppo Codex, Aleppo, 930. Jerusalem, Ben Zvi Institute, MS 1, f. 189v. © Courtesy of the Ben-Zvi Institute, Jerusalem. 57 Lám. 3 / Fig. 3. Códice M1, Toledo?, s. xIII. Codex M1, Toledo?, 12--. Madrid, Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, BH MS 1, f. 6r. © Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. 58 estos códices de manifiesto tanto en estas páginas de texto, como en las así llamadas páginas tapiz, que se encuentran al principio y al final de algunos códices, páginas magistralmente pintadas y cubiertas con complejos diseños ornamentales que traen a la memoria los que se encuentran en los tapices orientales (de ahí su nombre), y que imitan diseños islámicos contemporáneos. El códice medieval de la Biblia hebrea de Sefarad es heredero de biblias masoréticas anteriores de oriente Medio. No es del todo claro si la forma convencional de estas últimas llegó directamente a Sefarad desde oriente Medio, o si en algún momento entre los ss. Ix y xI el formato bíblico llegó a la Península Ibérica a través del Norte de África4. Fuese cual fuese la ruta por 4 Kogman-Appel la que el formato alcanzó la Penín(2004, 10–56) sula, lo cierto es que la localización reconstruye el contexto histórico de los distintos centros en el marco de este proceso. general del imperio islámico, que se extendía entonces por la mayor parte de oriente Próximo y el Norte de África llegando hasta al-Andalus, favoreció esos contactos. Desafortunadamente, ni una sola Biblia hebrea de la edad de oro andalusí (ss. xI–xII) ha sobrevivido y, en consecuencia, cualquier tesis sobre la forma de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad en lo que debió de haber sido el periodo formativo de su producción, no pasa de ser puramente conjetural. Aun así, el carácter anicónico y otras características propias de las biblias hebreas más tempranas, producidas en un contexto islámico, siguió siendo dominante en las biblias producidas en los reinos hispánicos, bajo gobierno cristiano hasta la expulsión de los judíos a finales del s. xv. Esta característica es ya visible en la primera Biblia hebrea sefardí datada (París, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. héb. 105), escrita en Toledo en 1197. En esa época, había pasado más de un siglo desde la conquista cristiana de esa ciudad, David Stern contemporary Islamic patterns—these codices display the strong impact of the Islamic book, particularly the Qur’an. The medieval Sephardic Hebrew Bible codex was the successor to the early masoretic Bibles from the Middle East. It is not clear whether the latter’s conventional form came directly from the Near East, or whether the biblical format reached the Iberian Peninsula through North Africa sometime between the ninth and eleventh centuries. 4 4 For a good Whatever the route by which the sketch of format reached the Iberian Peninthe historical sula, the connections between background, see these various centers were faciliKogman-Appel 2004, 10‒56. tated by their common location in the greater Islamic empire that covered almost the entirety of the Near East and North Africa through the Iberian Peninsula in southern Europe. Unhappily, not a single Hebrew Bible survives from the period of Islamic rule in Sepharad in the eleventh and twelfth centuries—the Andalusian Golden Age—and as a result, we are only able to conjecture about the shape of the Sephardic Hebrew Bible in what must have been its most formative period. Even so, the aniconicism and other features typical of earlier Hebrew Bibles produced in an Islamic context continued to characterize Bibles produced in the Hispanic kingdoms under Christian rule until the expulsion of the Jews at the end of the fifteenth century. This feature is evident in the earliest surviving dated Hebrew Bible from the Iberian Peninsula (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS héb. 105), written in Toledo in 1197. By then, Toledo had been Christian for more than a century (since 1085 C.E.). Even so, the mise-en-page of the 1197 Toledo Bible faithfully replicates that of the early Near ocurrida en 1085. Aun así, la mise en page de la Biblia de Toledo de 1197 replica de forma exacta la de los códices orientales más tempranos, con la única salvedad de que el texto aparece escrito en dos columnas en lugar de tres. Lo mismo se podría decir de una de las primeras biblias masoréticas decoradas de Sefarad (París, Bibliothèque nationale de France, ms. héb. 25), un libro relativamente pequeño (185 x 220 cm), escrito en Toledo en 1232, de nuevo a dos columnas. En este códice y en muchos otros el seder (pl. sedarim), es decir, la perícopa sinagogal semanal perteneciente al ciclo trienal, se marca por medio de la letra samekh inserta en un medallón decorativo floral, motivo que se deriva de la ansa que en coranes de época anterior se utilizaba para marcar las azoras. Esta costumbre de marcar tanto los sedarim trienales como las parashiyyot (sing. parashah, perícopa del ciclo anual) semanales deriva de códices masoréticos más tempranos, y su pervivencia en los reinos cristianos es digna de reseñar, pues es posible que en aquella época nadie siguiese utilizando el ciclo trienal. El mantenimiento de las divisiones en sedarim debía de ser una cuestión de tradición escrituraria. De hecho, su aparición anacrónica en las biblias hebreas de Sefarad es una prueba añadida en éstas del empeño de continuar tradiciones antiguas. En la Iberia medieval existían fundamentalmente tres tipos distintos de biblias hebreas. Esos tres tipos eran comunes a todos los centros judíos de producción de libros en Sefarad, Ashkenaz e Italia, aunque en cada centro se observan preferencias por algunos tipos concretos. En la Península Ibérica, la biblia masorética a la que he hecho referencia hasta aquí era la más común. Este tipo concreto solía incluir bien la TaNaKh completa (acrónimo de: Torah [Pentateuco], Nevi’im [Profetas, incluyendo Nevi’im rishonim (Profetas Anteriores) y Nevi’im aḥaronim Eastern codices with the single exception that the biblical text is written in two rather than three columns. The same is true of the earliest dated decorated masoretic Bible from Sepharad (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS. héb. 25), a relatively small book written in Toledo in 1232, again in double columns. In this codex and many others, the seder (pl. sedarim), that is the weekly synagogue reading as practiced in the triennial cycle, is marked by the letter samekh inscribed in a floral-like decorative medallion, which itself is another decorative pattern borrowed from early Qur’ans where the ansa decoration was used to mark sūra-s. This custom of marking both the triennial sedarim as well as the weekly parashiyyot (sing. parashah, pericope of the annual cycle) derives from the early masoretic codices, but its persistence in the Christian Hispanic kingdoms is even more remarkable inasmuch as probably no one in the world by this time still used the triennial cycle. The preservation of the seder-divisions must have been largely a matter of scribal tradition; indeed, its anachronistic preservation in Sephardic Hebrew Bibles testifies to the latter’s persistence in continuing the earlier traditions. In medieval Iberia, there existed essentially three different types of Hebrew Bibles. These three types were common to all medieval Jewish centers of book culture in Sepharad, Ashkenaz and Italy, but different centers seemed to have preferred different types. In the Iberian Peninsula, the most commonly produced Bible was the masoretic Bible I have been discussing. This type tends to comprise either a complete TaNaKh—the traditional acronym for the entire Hebrew Bible in its three traditional sections, namely, Torah [Pentateuch], Nevi’im [Prophets, including both Nevi’im rishonim [Former Prophets] and Nevi’im aḥaronim [Latter Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 59 60 (Profetas Posteriores)], y Ketuvim [Escritos o Hagiógrafos]), o bien una o dos secciones de la misma. Los colofones de algunas copias indican explícitamente que el escriba solo copió una sección, por ejemplo, Nevi’im o Ketuvim, por lo que sabemos que en ocasiones algunas secciones de la TaNaKh se copiaban solas. Cuando no hay colofón con indicación explícita al respecto, es imposible determinar si un determinado volumen que hoy solo contiene Profetas y Hagiógrafos es el resto que nos ha llegado de un códice en varios volúmenes. De igual modo, existen Pentateucos masoréticos que no van acompañados las otras dos secciones. La Biblia masorética (lám. 4) se define fundamentalmente en función del contenido que hemos descrito: texto bíblico vocalizado y acentuado, con marcas de cantilación, habitualmente dispuesto en dos o tres columnas, y anotaciones masoréticas, que generalmente incluyen masora parva y magna, escritas en micrografía, la primera en los espacios que hay entre las columnas del texto, y la segunda en los márgenes superior e inferior de la página. Dependiendo de su origen, los códices masoréticos pueden o no incluir signos de parashah y/o seder en los márgenes, así como los tratados y listas masoréticas que preceden o siguen al texto bíblico al comienzo o al final del códice. Salvo en raras ocasiones, las páginas de estas biblias no contienen ningún otro texto, aparte del propio texto bíblico y la masora. El título que los propios colofones suelen dar a estos volúmenes es, o bien esrim ve-’arba (veinticuatro [libros]), cuando incluyen toda la TaNaKh, o Torah, Nevi’im u-Khetuvim. En algunos casos, la Biblia masorética era también un sefer mugah o tikkun (códice modelo). A diferencia del moderno tikkun, con sus dobles columnas de texto (una de ella presentada tal y como aparece David Stern Prophets], and Ketuvim [the Writings or the Hagiographa])—or one or two of the sections alone. Because the colophons of some volumes explicitly state that the scribe wrote only a single section—Nevi’im or Ketuvim, for example— we know that parts of the complete TaNaKh were sometimes copied alone, but where there is no colophon with an explicit statement to this effect, it is impossible to determine as to whether or not an existing volume now containing only the Prophets or the Hagiographa is the survivor of a once-complete set of codices. Similarly, there exist stand-alone masoretic Pentateuchs. The masoretic Bible (Fig. 4) is essentially defined by its contents—the vocalized and accentuated biblical text with cantillation marks, typically presented in either two or three columns, and the masoretic annotations, usually both the masora parva and magna written in micrography, the former in the spaces between the text-columns, the latter on the top and bottom page margins. Depending on where they were produced, masoretic codices frequently contain either or both parashah and seder signs in the margins of the text as well as masoretic treatises and lists that either precede or follow the biblical text at the codex’s beginning or end. Rarely, however, do the Bible-pages themselves contain texts other than the Bible and the masorah. The typical title for these volumes as they are called in their colophons is either esrim ve-’arba (twenty four [books]), if they contain the entire TaNaKh, or Torah, Neviʼim, u-Khetuvim. In some cases, the masoretic Bible was also a sefer mugah or tikkun (model book). Unlike the modern tikkun, with its double-columns of the same text—one presented as it appears in a Sefer Torah , the other printed with the 61 Lám. 4 / Fig. 4. Biblia, s. xv? Bible, 14--? Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, vITR/26/6, f. 378v. © Biblioteca Nacional de España. 62 en un Sefer Torah, y la otra impresa con signos de vocalización y cantilación, formato cuyo objeto es ayudar a memorizar la manera correcta de recitar en alto el texto bíblico a partir de un Sefer Torah durante el servicio sinagogal), el tikkun medieval era un códice bíblico escrito con particular cuidado que les servía de modelo a los copistas que escribían Sifre Torah y, es de imaginar que otros libros modelo o códices bíblicos en general. Probablemente el más famoso de todos los códices sefardíes sea el códice modelo que se conoce con el nombre de Sefer Hilleli o códice Hilleli, que se dice fue escrito en torno al año 600, aunque lo más probable es que fuese en torno al año 1000, en la ciudad de León. El códice original existía todavía y era consultado y copiado en 1197, momento en que los almohades atacaron las comunidades de Castilla y Aragón y se llevaron al menos parte de ese códice. Una copia parcial del mismo, que incluye el Pentateuco, se completó en Toledo en 1241 y se conserva en la actualidad en los fondos del Jewish Theological Seminary of America (ms. L 44a). Entre otros detalles, el códice Hilleli incluía signos extraordinarios, como los tagin (coronas o trazos ornamentales en la parte superior de las letras) y ciertas letras escritas de forma especial (otiyyot meshunot), pruebas adicionales que confirman que los copistas lo utilizaban efectivamente como modelo. El segundo tipo de Biblia usada por los judíos en la Edad Media era el ḥummash (Pentateuco litúrgico), es decir, un Pentateuco acompañado de las haftarot (sing. haftarah, lecturas de los Profetas que se recitaban en la sinagoga durante la lectura semanal de la Torah), los cinco rollos (Eclesiastés, Ester, Cantar de los Cantares, Lamentaciones y Rut), habitualmente el Targum (en la mayoría de los casos el de onquelos, y en algún caso excepcional otro distinto), y en zonas arabófonas (como al-Andalus y Yemen) David Stern vocalization and cantillation marks—and which is primarily intended to help its users memorize the proper way to chant aloud from a Sefer Torah in the synagogue service, the medieval tikkun was a biblical codex written with special care so as to serve as an exemplar for scribes writing a Sefer Torah or Biblical codex. Probably the most famous of all such Sephardic codices was a model codex known as the Sefer Hilleli, or Hilleli Codex, reputed to have been written around the year 600 C. E. but, more probably, around the year 1000, in the city of León. The original was still in existence in 1197 C. E. when the Almohades attacked the Jewish communities of Castile and Aragon and carried away at least part of the complete codex, and it was both consulted and copied. one such copy, albeit only the Pentateuch section, was completed in Toledo in 1241 and survives to this day in the collection of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America (MS L 44a). Among its singular features, the Hilleli Codex recorded the extraordinary tagin (crownlets or ornamental strokes atop letters) as well as certain peculiarly shaped letters (otiyyot meshunot), further evidence of its use as an exemplar for scribes. The second type of Bible used by medieval Jews was a ḥummash (liturgical Pentateuch), namely, a Pentateuch accompanied by the haftarot (sing. haftarah; readings from the Prophets that are chanted in the synagogue following the weekly Torah reading); the Five Scrolls (Ecclesiastes, Esther, Song of Songs, Lamentations, and Ruth); and usually the Aramaic Targum, typically onkelos, though in a few cases other Aramaic Targumim and in Arabic-speaking locales like al-Andalus and Yemen, the Tafsīr (Arabic translation) of the great Geonic-period sage Saadiah Gaon (Egypt, 882/892‒Baghdad, 942). In some codices, the commentary of the el Tafsīr (traducción árabe) del gran sabio del periodo gaónico Saadiah Gaón (Egipto, 882/892–Bagdad, 942). Como veremos, también el comentario del famoso exegeta del s. xI Rashi (Salomón ben Isaac, 1040–1105) se incluye en ocasiones en estos volúmenes, unas veces acompañado del Targum, y otras en sustitución del mismo. He denominado este tipo de biblia «litúrgica» porque su contenido parece corresponder con las secciones de la Biblia que se leían en la sinagoga el sábado y durante las fiestas, aunque se desconoce qué uso específico podía tener en la sinagoga o fuera de ella. Tanto el Targum como otras traducciones arameas aparecen unas veces en columnas separadas, y otras en el cuerpo del propio texto de la Torah, en cuyo caso los versículos van alternando con la traducción o el comentario. En ocasiones, estos libros también incluyen los Sifre EMeT (Job, Proverbios y Salmos), así como la Megillat Antiochus [Rollo de Antíoco], relato medieval sobre la revuelta macabea que se leía en la sinagoga durante la fiesta de Ḥanukkah, y capítulos del libro de Jeremías que era tradicional leer durante el día de ayuno de Tish‘ah be-’av (Nueve de av). En los colofones, estos libros aparecen habitualmente descritos como ḥummashim (o ḥamishah ḥummeshe Torah). El tercer tipo de Biblia que encontramos entre los judíos en la Edad Media es la biblia de estudio. Es cierto que tanto la Biblia masorética como el Pentateuco litúrgico se usaban también para estudiar, pues ¿qué Biblia hebrea no se estudiaba?, pero estos códices parecen haber sido compuestos con el propósito específico de servir para el estudio. Así, incluyen múltiples comentarios en la misma página, que con frecuencia se acompañan de Targum o Tafsīr. A lo largo de la Edad Media, y al margen de biblias de estudio de este tipo, los comentarios no solían aparecer celebrated eleventh-century exegete Rashi (Solomon ben Isaac, 1040‒1105) is also included in these volumes, at times as a substitute for the Targum, at other times in addition to it. I have called this type of Bible “liturgical” because its contents seem to correspond to the sections of the Bible that were read in the synagogue on the Sabbath and holidays; however, their precise use in the synagogue or outside it remains to be discussed. The Targum or other Aramaic translations are sometimes recorded in separate columns; at other times, they are presented in the body of the Torah text itself, alternating verse and translation or commentary. on occasion, these books also include the Sifre EMeT (Job, Proverbs, and Psalms), as well as Megillat Antiochus [Antiochus Scroll], a medieval account of the Maccabean Revolt that was read in the synagogue on the festival of Ḥanukkah, and chapters from the prophet Jeremiah that were read on the fast day of Tish‘ah be-’av (Ninth of Av). Typically, these books are called in their colophons ḥummashim (or ḥamishah ḥummeshe Torah). The third type of Bible in circulation among Jews in the Middle Ages was the study-Bible. While both masoretic Bibles and liturgical Pentateuchs were certainly used for study as well— what Jewish Bible has not been studied?— these codices appear to have been composed specifically for the purpose of Bible study, a function indicated by such features as that they contain multiple commentaries on the same page, often with the Targum or Tafsīr. Aside from study-Bibles of this kind, commentaries were generally not reproduced on the same page as the biblical text but were recorded and studied from separate books called quntresim (sing. quntres, from the Latin quinterion , a quire of five sheets). The one exception was Rashi but, as noted earlier, Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 63 64 en la misma página que el texto bíblico, sino que eran escritos y estudiados en libros separados llamados quntresim (sing. quntres, del latín quinterion, cuaderno de cinco folios). La única excepción era Rashi, aunque, como ya se ha observado, su comentario solía sustituir al Targum arameo. Además de estos tres tipos principales, había varios sub-tipos de biblias, o secciones de biblias, que se producían como libros separados. Se trata de los salterios (que a veces se decoraban, e incluso se ilustraban, y que con frecuencia contenían comentarios que también debían de servir para el estudio) y de códices separados que contenían únicamente las haftarot, y/o los cincos rollos. En el ensayo sobre el arte de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad que aparece en este mismo volumen, K. Kogman-Appel identifica varios periodos distintos en la historia de la Biblia hebrea sefardí desde mediados del s. xIII a finales del s. xv. El lector puede encontrar en él los detalles de esa historia. Aquí me gustaría únicamente tratar brevemente dos características inusuales que surgen durante su desarrollo y que son cruciales para entender el sentido que la Biblia tenía para los judíos en la Península Ibérica. La primera de esas características es la pervivencia, en las biblias hebreas escritas en los reinos cristianos de la Península, de una serie de características propias de las biblias orientales, a las que ya se ha hecho referencia. La segunda es el uso de la representación de los utensilios del Templo en un grupo de aproximadamente veinticinco biblias producidas en la Corona de Aragón principalmente en la primera mitad del s. xIv. Estas aparecen generalmente al comienzo del códice bíblico, como si de una página tapiz se tratase (lám. 5). La pervivencia de elementos que eran característicos de la biblias orientales, como el carácter David Stern his commentary was often reproduced in order to take the place of the Aramaic Targum. In addition to these three main types, there were several sub-types of Bibles or portions of the Bible that were produced as separate books. These include Psalters which were sometimes decorated and even illustrated, and often contained commentaries that must also have been used for study. There also existed separate codices containing the haftarot alone, or the Five Scrolls, or both. In her essay in this volume on the art of the Hebrew Bible in Sepharad, K. Kogman-Appel identifies several distinct periods in the history of the Sephardic Hebrew Bible between the mid-thirteenth and late fifteenth centuries. The reader is referred to that essay for the details of that history; here I wish only to deal briefly with two unusual features that emerge from the history of the Hebrew Bible in Sepharad that are critical to understanding the meaning that the Bible held for Jews in the Iberian Peninsula. The first of these features is, as already noted, the persistence in the Hebrew Bibles produced in the Hispanic Christian kingdoms of features which were typical of earlier Bibles produced in the Near East within Islamic realms. The second is the use of Temple implement illustrations in a group of approximately twenty-five Bibles produced in the Crown of Aragon mainly in the first half of the fourteenth century. These illustrations are usually found at the beginnings of the Bible codex almost like carpet pages (Fig. 5). The retention of the features of the early Near Eastern Bible—particularly the aniconicism inherited from Islam and the use of carpet pages—in the Hebrew Bibles produced in Christian Iberia is characteristic of the contemporary Mudejar style in the Hispanic kingdoms, 65 Lám. 5 / Fig. 5. Biblia de Perpiñán, Perpiñán, 1299. Perpignan Bible, Perpignan, 1299. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS héb. 7, ff. 12v‒13r. © Bibliothèque nationale de France. 66 anicónico heredado del Islam o la presencia de páginas tapiz, en las biblias hebreas producidas en la Iberia cristiana está en sintonía con el arte mudéjar de los reinos hispánicos, en particular durante los ss. xIII y xIv; este estilo es ecléctico e híbrido, el estilo de la convivencia, una simbiosis nacida del intercambio entre las poblaciones cristiana, musulmana y judía (Mann, Glick, y Dodds 1991, 113–132). Sin embargo, hay que destacar la consistencia con la que las biblias hebreas parecen rechazar la cultura del libro cristiano de la época y, con algunas notables excepciones, aquellos elementos que se perciben como «góticos». Esta preferencia por los modelos derivados del arte islámico y por el arte mudéjar de la época no es privativa de los libros judíos. También se produce en la arquitectura de las sinagogas que los judíos construyeron en los siglos xIII, xIv y xv en Sefarad: edificios como Santa María la Blanca de Toledo, construido en el s. xIII, la sinagoga de Córdoba, erigida en el primer cuarto del s. xIv, la sinagoga de Segovia (hoy Iglesia del Corpus Christi), construida en 1419; y la más famosa de todas ella, El Tránsito, levantada en Toledo en 1360. Las monumentales inscripciones en esta última son reminiscentes de las inscripciones que enmarcan las páginas tapiz y los utensilios del Templo en las biblias sefardíes masoréticas. Todos estos edificios, de estilo mudéjar, no comparten con el arte religioso cristiano sus principales características arquitectónicas. Las biblias sefardíes muestran esas mismas tendencias. Ninguna comparte las principales características de las biblias cristianas producidas en Iberia durante ese periodo, y casi todas resisten el tipo de ilustraciones representacionales y narrativas que dominan el arte del libro cristiano. La única excepción a la regla son las ilustraciones de los utensilios del Templo, pero estas no son narrativas, sino páginas decorativas David Stern particularly in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries; this style was eclectic and hybrid, the style of convivencia, a symbiosis born of the interchange between its Christian, Islamic, and Jewish populations (Mann, Glick, and Dodds 1991, 113‒132). Nonetheless, it is noteworthy how consistently the Sephardic Bibles seem to have rejected their contemporary Christian book culture and—with a few notable exceptions—elements perceived as “Gothic.” This tendency to cling to the traditional Islamically-derived models and to the influences of contemporary Mudejar style is not unique to Jewish books. It also informs the architecture of the synagogues Jews built in thirteenth-, fourteenth-, and fifteenthcentury Sepharad—buildings like Toledo’s Santa María la Blanca, built in the thirteenth century; the Cordoba synagogue, erected in the first quarter of the fourteenth century; the synagogue in Segovia (currently Iglesia del Corpus Christi), constructed in 1419; and the most famous of them all, El Tránsito, erected in Toledo in 1360. The monumental inscriptions in the last synagogue are reminiscent of the inscriptions that frame the carpet pages and Temple implement pages in Sephardic masoretic Bibles. All these buildings, constructed in the Mudejar style, depart from the central defining features of contemporary Christian religious architecture. The same tendency informs the Sephardic Bibles. None adapt the main stylistic elements found in Christian Bibles produced in Iberia during this period, and nearly all resist the kind of representational, narrative illustrations that dominate Christian book art. The one exception to this rule is the Temple implements illustrations, but these are not narrative drawings so much as decorative pages resembling the carpet pages in earlier Castilian or Near Eastern Hebrew Bibles. This tendency to avoid contemporary Christian que recuerdan a las páginas tapiz de biblias hebreas castellanas u orientales anteriores. Esta tendencia a evitar los elementos cristianos de ese período parece ir en contra de una de las reglas principales de la cultura del libro judío, y que es la tendencia a reflejar los elementos de la cultura mayoritaria. ¿Por qué se evitaron los judíos de la Península Ibérica las características de los libros cristianos y optaron por los elementos derivados del arte islámico y del estilo mudéjar? En parte pudo tratase de continuidad con la tradición, pero seguramente fue más que eso. El hábito pudo estar puesto al servicio de un objetivo «politizado», acorde con la época. Siendo forma de resistencia a la cultura dominante cristiana, pudo haberle servido a los judíos, como minoría cultural, para identificar no solo sus libros, sino a ellos mismos, con la otra cultura minoritaria de los reinos hispánicos: la de los mudéjares, que rechazaba, de forma similar, modelos que eran percibidos como cristianos. Sumarse a esa tendencia pudo haber tenido un significado especial en el s. xIII, cuando se estaban produciendo las violentas dislocaciones de la conquista cristiana del sur, y sobre todo a finales del s. xIv, cuando se produjeron las persecuciones de 1391, las conversiones forzadas resultantes, el fallo de las predicciones apocalípticas que apuntaban a comienzos del siglo xv, y la desilusión que debió seguir al fallo de las mismas. Estos vecinos mudéjares no suponían ninguna 5 El argumento amenaza para los judíos sefardíes, que aquí presento y estos últimos, al identificar sus es muy similar libros y sus sinagogas con la tradial que aparece ción material mudéjar, fueron caen Frojmovic paces de resistir la hegemonía cris2002 y 2010. tiana para autodefinirse como cultura minoritaria5. Sabemos por muchos otros casos que la forma material de un texto canónico elements would seem to violate one of the cardinal rules of Jewish book-culture: namely, the tendency for Jewish books to reflect those of the host culture. Why did the Jews of Iberia so regularly avoid the features of Christian books in their Bibles and cling to the Islamically-derived features of Mudejar style? In part, it may have been a reflex of traditionalism, but it was surely more than that as well. The habit may have served a more contemporary, “politicized” purpose. As a path of resistance to the dominant Christian culture, it may have functioned as a way for Jews to identify not only their books but themselves, a minority culture, albeit an active one, with the other contemporary minority culture in the Hispanic kingdoms, that of the Mudejars who, in a similar vein, rejected models which they perceived as Christian. Adhering to these tendencies would have held special meaning in the thirteenth century which witnessed the violent dislocations of the Christian conquest of the south and, even more so in the fourteenth century, with the 1391 persecutions, the forced conversions that followed them, the failure of the apocalyptic expectations predicted for the beginning of the fifteenth century, and the disappointment that must have followed upon the failure of those expectations. Their Mudejar neighbors posed no threat to the Sephardic Jews, and the Jews, by identifying their books, and synagogue buildings, mate- 5 My argument rially with Mudejar tradition, here is very were able to resist Christian hege- close to the one made by mony and to define themselves as Frojmovic 5 a minority culture. We know 2002 and 2010. from many other cases that the material shape of a canonical text can serve to shape religious identity. Here the material Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 67 68 puede contribuir a formar la identidad religiosa. Aquí la forma material de la Biblia hebrea estaría puesta al servicio de la autodefinición cultural. Se puede dar una explicación similar al florecimiento de la representación de los utensilios del Templo en las biblias del s. xIv que proceden del Rosellón y Cataluña, que no se leían de forma aislada, o como simples imágenes, sino en conjunción con los textos inscritos en los marcos monumentales de estilo mudéjar que los rodeaban, al menos en aquellos casos en los que existen marcos, pues no todas las representaciones de los utensilios del Templo los exhiben. Estos textos son los siguientes: 1) versículos como Éx 25,34 y Nú 8,4 que tratan sobre los utensilios del Templo, en particular sobre la menorah; 2) versículos que piden la reconstrucción del Templo; 3) otros, generalmente del libro de Proverbios (por ej., 2,3–11; 3,1–3; 6,23), y de Job (18,16) que alaban la Torah y la sabiduría mediante metáforas y símiles que comparan los mandamientos con ner (lámpara) y la Torah con or (luz) (sobre todo Pr 6,23), o que comparan el valor de la sabiduría, la Torah y los mandamientos con plata, oro, ónice, zafiros, etc. El efecto general de estos versos inscritos es judaizar los utensilios representados en la imagen enmarcándolos con las palabras de la Biblia hebrea. Esto no solo resulta relevante por el hecho de que los utensilios del Templo (en la medida en que eran vestigios preciados, únicos restos del Templo destruido de Jerusalén) eran objeto de disputa entre judíos y cristianos en la Edad Media, sino porque desde la Antigüedad tardía y durante el periodo medieval ambas tradiciones, en sus respectivos contextos apocalípticos, vaticinaban la recuperación de los utensilios del Templo. La representación de los utensilios del Templo en libros cristianos se remonta al David Stern shape of the Hebrew Bible served as a medium of cultural self-definition. An analogous explanation may lie behind the efflorescence of Temple implement illustrations in the Roussillon and Catalan Bibles of the fourteenth century. These illustrations should be read not in visual isolation or as mere images but together with the texts inscribed in monumental frames around them (at least where there are such verses). These texts are: 1) Biblical verses like Exod 25:34 and Num 8:4 that relate directly to the Temple implements, the menorah in particular; 2) verses that pray for the rebuilding of the Temple; and (3) others that praise Torah and wisdom, usually through a mélange of verses from Proverbs (eg. 2:3‒11; 3:1‒3; 6:23) and Job (18:16), which often use metaphors and similes that liken the commandments to a ner (lamp) and Torah to or (light) (Prov 6:23 in particular) or that compare the value of wisdom, Torah, and the commandments to silver, gold, onyx, sapphires, and so on. The overall effect of these inscribed verses is to judaize the implements illustrated in the picture by explicitly framing them with the words of the Hebrew Bible. This is not insignificant because the Temple implements—the treasured spoils of the destroyed Jerusalem Temple—were fiercely contested objects in the religious imaginations of Jews and Christians in the Middle Ages. In the late antique and early medieval periods, both traditions foresaw the restoration of the Temple implements as part of their respective apocalyptic scenarios. Illustrations of the implements were found in Christian books going back to the seventh-century Codex Amiatinus, which itself derived from the sixth-century Codex Grandior of Cassiodorus, as well as in Iberian Bibles from the tenth through thirteenth century and in códice Amiatinus (s. vII), que a su vez deriva del códice Grandior (s. vI) de Casiodoro; aparece también en biblias producidas en la Península Ibérica entre los ss. x y xIII, y en manuscritos de la Historia Scholastica de Pedro Coméstor (m. 1178–1180) (Williams 1965; Kuenel 1999, 13–14; Nordström 1964)6. En conjunción 6 Según Nordström, con las especulaciones mesiánicas las ilustraciones comunes entre los judíos de Catadel manuscrito de luña, y en general de Sefarad, a raMadrid, Biblioteca íz de la disputa de Barcelona en 1263 Nacional de (disputa que, de hecho, giró en torEspaña, RES/199, no a la veracidad de los conceptos están directamente basadas en mesiánicos cristianos y judíos), y modelos judíos. con los anhelos de establecer fechas que señalaran la llegada del periodo mesiánico en torno a 1358 y 1403, los utensilios del Templo y su representación empezaron a poseer un enorme poder simbólico. En la exégesis judía que se escribe en este periodo, se prestó a los utensilios del Templo una nueva y especial atención, como se puede ver en el comentario popular, cuasi-cabalístico de Baḥya ben Asher (Zaragoza, m. 1349), alumno de Naḥmánides. En su comentario a Éx 25,9, dice Baḥya: «es bien sabido que el Tabernáculo y sus utensilios eran ṣiyyurim gufaniyyim (imágenes materiales) [cuyo propósito era] hacer comprensible las elyoniyyim (imágenes divinas) a las que servía de modelos» (Chavel 1966–1968, 2:268). Pasa a explicar entonces el sentido espiritual de cada uno de los utensilios y concluye: «Es importante decir que aunque [...] los utensilios materiales del Templo estaban destinados a ser destruidos con la golah (diáspora), no has de pensar que [...] sus formas y modelos dejaron de existir le-ma‘alah (en lo alto). Continúan existiendo y existirán para siempre» (Chavel 1966–1968, 2:288–289). Baḥya parece aludir aquí específicamente a la imagen de estos utensilios. a fourteenth-century Iberian manuscript of the Historia Scholastica of Peter Comestor (d. 1178‒1180) (Williams 1965; Kuenel 1999, esp. 13‒14; Nordström 1964). 6 In con6 Nordström junction with the messianic expecargues that the tations that were current among illustrations in Catalan and other Sephardic Jews the manuscript in following the Barcelona Disputa- Madrid, Biblioteca tion of 1263—a disputation which Nacional de itself largely revolved around the España, RES/199, messianic doctrines of Christiani- were directly ty and Judaism and their respec- based on tive veracity—and the longings for Jewish models. “end-dates” signalling the arrival of the messianic period around 1358 and 1403, the Temple implements and their illustrations came to possess an especially powerful symbolic force. In Jewish biblical exegesis of the period, the implements also gained a new and special attention as can be seen in the popular, quasiKabbalistic commentary of Baḥya ben Asher (Saragossa, d. 1340), a student of Naḥmanides. In his commentary on Exod 25:9, Baḥya explains that “It is known that the Tabernacle and its implements were all ṣiyyurim gufaniyyim (material images) [that were intended] to make comprehensible the elyoniyyim (divine [images]) for which they were a model” (Chavel 1966‒1968, 2:268). He then explicates the spiritual meanings of each of the implements, and concludes, “And it is important to say that even though…the holy material Temple implements were fated to be destroyed in the golah (Diaspora), you should not imagine that…their forms and models ceased to exist le-ma‘alah (in the higher world). They continue to exist and will exist forever” (Chavel 1966‒1968, 2:288‒289). What Baḥya seems to be indicating is specifically the image of these implements. Precisely Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 69 70 Precisamente porque se pensaba que las imágenes de los utensilios situadas al comienzo del códice, a modo de páginas tapiz, poseían poderes espirituales, estos constituyen marcas del carácter «judío» de esas biblias. El significado simbólico que se atribuye a las biblias que contienen representación de los utensilios del Templo viene además sugerido por el hecho de que, a partir del s. xIv, los códices bíblicos masoréticos de lujo que se producen en Sefarad se suelen denominar miqdashyah (lit. templo de Dios), como es el caso de una biblia que es parte de esta exposición, y que actualmente está en la Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, BH ms. 2 (entrada cat. 3). Algunos de estos códices, aunque no todos, contienen representaciones de los utensilios del Templo, y en ese sentido son libros que realmente se explican a sí mismos y materializan su semejanza con el santuario a través de las representaciones de los utensilios del Templo. El uso del término, sin embargo, no se documenta por primera vez en el s. xIv, pues la conexión entre el Tabernáculo y la Torah se puede remontar a Qumrán y fue común entre los caraítas. Sin embargo, tal y como fue entendido por los exegetas bíblicos sefardíes, el término transmite la idea de que el códice de la Biblia hebrea ocupaba en la sociedad judía de la Península Ibérica el lugar de un santuario sagrado. La explicación más extensa del término miqdashyah aparece en el tratado gramatical Ma‘aseh efod [La producción del efod], escrito en 1403 por el polemista y gramático catalán Isaac ben Moisés ha-Levi, conocido como Profiat Durán (1360–1412). Durán le atribuye al estudio de la Biblia un mérito inherente, un «poder artefactual» en palabras de K. Bland. Llega incluso a considerar las biblias de estudio como auténtica David Stern because the pictures of these implements—placed at the very beginning of the codex—were believed to possess spiritual power they were also able to serve as markers of the Jewishness of these Bibles. The symbolic meaning imputed to Bibles containing images of the Temple implements is also exemplified by the fact that, beginning in the fourteenth century, deluxe masoretic Bible codices in Sepharad are often called by the term miqdashyah (lit. the sanctuary of the Lord) as is the case with one Bible in this exhibit, held in the Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (BH MS 2) (cat. entry 3). Some of these codices, though by no means all, contain Temple-implement illustrations, and are thus virtually self-reflexive books embodying their sanctuary-likeness through their illustrations of the Temple implements. The use of the term was not, however, a fourteenth-century invention and did not derive from the presence of Temple implement illustrations. The connection between the Tabernacle and the Torah can be traced back to Qumran and continued with the Karaites. But as it was understood by contemporary Sephardic biblical exegetes, it captured the place that the Hebrew Bible codex occupied in Iberian Jewish society as a kind of sacred sanctuary. The most extensive explication of the term miqdashyah is found in the introduction to the grammatical treatise Maʻaseh efod [The Making of the Efod], composed in 1403 by the Catalonian polemicist and grammarian Isaac ben Moses Ha-Levi, better known as Profiat Duran (1360‒1412). In this work, Duran attributes to Bible study an inherent merit, indeed a virtual “artifactual power,” as K. Bland has called it. He even calls Bible-study the true avodah (worship) avodah (culto) a Dios (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 14)7. Para Durán, la Torah poseía una segullah, término polisémico este que signi7 Sobre Durán, fica tanto reliquia como fuente de véase Gutwirth poderes especiales, a modo de amu1991; Bland 2000, leto. Así, escribe Durán: «el simple 82–91; y Zwiep 2001, 224–239. eseq (uso), hagiyyah (recitación) y qeri’ah (lectura) [sin comprensión] son parte del culto, y de aquello que contribuirá a que la influencia y providencia divinas desciendan a través de la segullah inherente a las mismas, porque también ésta es la voluntad de Dios» (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 13). De hecho, continúa, Dios preparó específicamente la Torah para el tiempo en que Israel iba a estar en exilio, para que de ese modo le pudiera servir de miqdash me‘at (templo menor), en cuyas páginas se pudiera encontrar la presencia de Dios, al igual que antes se encontraba entre los muros del Templo. De forma análoga, afirma que el estudio de la Torah puede expiar los pecados, como en el pasado lo habían hecho los sacrificios (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 11). En opinión de Durán, el estudio de la Torah estaba tan relacionado con el destino de Israel que el rechazo del mismo entre los judíos de Ashkenaz, a causa de su lamentable dedicación al estudio del Talmud, había ocasionado la persecución y las tribulaciones que estos sufrían en el s. xIv. De igual modo, escribe Durán, los judíos de Aragón se salvaron de la destrucción gracias al shimush tehillim (recitación de los Salmos), un tipo de lectura devocional de los salmos que tenía poderes teúrgicos. Esta concepción del poder del códice bíblico se puede apreciar mejor si se sitúa en el contexto histórico en el que vivió Durán, es decir, entre los años 1391 y 1415, momento en el que la Iglesia en la Península Ibérica se embarcó en una misión particularmente virulenta contra of God (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 14). 7 For Duran, Torah possesses a segullah , a charged term that means both a “treasured 7 on Duran, heirloom” and a virtually amuletic see Gutwirth 1991; source of special power. Thus, he Bland 2000, writes, “even eseq (engagement), 82‒91; and Zwiep hagiyyah (recitation), and qeri’ah 2001, 224‒239. (reading) alone [without comprehension] are part of avodah (worship) and of that which will help to draw down the divine influence and providence through the segullah that adheres in them, because this too is God’s will” (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 13). Indeed, he continues, God specifically prepared the Torah for Israel in its time of exile, so that it could serve as a miqdash me‘at (small sanctuary), within whose pages God’s presence might be found just as it formerly was within the four walls of the Temple; analogously, he claims that study of Torah atones for sins just as sacrifices once did (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 11). Indeed, in Duran’s view, the study of Torah is so implicated in the fate of Israel that its neglect by the Jews of Ashkenaz, because of their lamentable concentration upon Talmud study, led to their persecutions and travails in the fourteenth century. So too, Duran writes, the Jews of Aragon were saved from destruction only because of their shimush tehillim (recitation of Psalms), a kind of devotional reading of Psalms with its own theurgic powers. This conception of the Bible codex’s power can be better appreciated if it is seen against the background of Duran’s time, the years between 1391 and 1415 when the Church in the Iberian Peninsula embarked upon an especially virulous mission against the Jews living in its realms. By emphasizing the Bible’s artifactual power, Duran was offering his contemporaries an avenue of salvation that was immediately available to them, a sacred shelter inside of which Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 71 72 los judíos. Al enfatizar el poder artefactual de la Biblia, Durán les estaba ofreciendo a sus contemporáneos un medio de salvación que les fuera accesible, un refugio sagrado dentro del cual se pudieran dedicar al estudio de la Torah y en consecuencia pudieran defenderse de la hostilidad del mundo exterior. Esta era la fuerza real de la analogía del Templo, tal y como Durán la concebía. No resulta difícil imaginar que, al contemplar las páginas tapiz con la representación de los utensilios del Templo, un judío sefardí del s. xIv sintiese la conexión palpable entre la presencia divina que habitaba el Templo y la Biblia material que contenía esas imágenes. Por muy angustiosa que fuese su situación histórica, estas biblias hacían que sus poseedores y lectores encontrasen en sus páginas la reconfortante presencia de Dios. Para Durán, el principal objetivo del estudio de la Biblia era memorizar el texto, y para cumplir ese objetivo, Durán subraya la dimensión material del códice bíblico. Así, le recomienda al estudiante escribir simanim (marcas) mnemotécnicos, al parecer en los márgenes del texto, leer siempre del mismo libro, escribir el texto en letra cuadrada asiria con trazos gruesos y marcados, «porque por su belleza esta escritura deja una huella permanente en el sentido común y en la imaginación», y más importante todavía, recomienda «estudiar siempre en libros de bella factura, escritura y páginas elegantes, y adornos y encuadernaciones ornados, y que la construcción de las bate ha-midrash (casas de estudio) sea bella y hermosa, pues todo ello favorece que se le tenga amor al estudio» (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 19). A la hora de justificar estas recomendaciones, Durán vuelve a hacer referencia a la analogía del Templo, diciendo que solo es apropiado decorar y adornar «este sagrado libro que David Stern they could occupy themselves in Torah study and thereby defend themselves against the hostile world outside. This was the real force of the Temple analogy as Duran used it. Indeed, it is not difficult to imagine how a fourteenth-century Sephardic Jew, looking at the carpet pages with Temple implement illustrations on them, would have felt the palpable connection between the divine presence dwelling in the Temple and the material Bible containing those images. These Bibles provided their owners and readers with a sense of the comforting presence of God within their pages no matter how beleaguered their historical situation. For Duran, the principle goal of Bible-study was memorization of the text, and to accomplish this task, Duran emphasized the material dimension of the Bible codex. Thus, he writes, the student should place mnemonic simanim (notes), presumably in the margins of the text; he should always read from the same book; the text studied should be written in square, Assyrian letters inscribed in bold and heavy strokes, “for because of its beauty the impression of this script remains in the common sense and in the imagination”; and most significant of all for our concerns, “one should always study from beautifully made books that have elegant script and pages and ornate adornments and bindings, and the places of study—I mean, the bate ha-midrash (study-houses)—should be beautifully constructed and handsome, for this enhances the love of study and the desire for it” (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 19). To justify these recommendations, Duran drew again upon the Temple analogy, saying that it is only fitting to decorate and beautify “this sanctified book which is a miqdashyah” because it was God’s will that the sanctuary itself be decorated and ornamented with silver es una miqdashyah» porque fue la voluntad de Dios que el propio santuario estuviera decorado y ornado con oro, plata y piedras preciosas. Por ese motivo, añade Durán, siempre será de ayuda que los estudiosos de la Biblia sean adinerados, para poder así poseer sus propios libros y no tener que pedirlos prestados. Asimismo, escribe Durán con cierto desprecio, a los mecenas ricos de esta época les parece que simplemente «con poseer estos libros les basta para vanagloriarse, pensando que al guardarlos en sus cofres los están guardando en sus mentes» (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 21). Aunque sin convicción, al no ser capaz de negar la existencia y el poder social de estos aristócratas, Durán asegura que, aun así, «sus acciones aún tienen cierto mérito, pues consiguen que la Torah sea magnificada y exaltada, y sin ser merecedores de ello, les reportan bendición a sus hijos y descendientes» (Friedländer y Kohn 1865, 21). En ello reside el auténtico poder artefactual de la Biblia, en que puede ayudar incluso a quienes no lo merecen. Durán sabía perfectamente que las lujosas biblias concebidas a modo de templos que estos ricos aristócratas encargaban (los únicos judíos de la Península Ibérica cuya economía se lo permitía), eran «libros trofeo», destinados a convertirse en ostentosas muestras de riqueza. Muchas de las biblias que se recogen en esta exposición fueron probablemente objetos de ostentación. De forma un tanto paradójica, como ya he mencionado, parece que la producción de estos libros, que ricos mecenas judíos encargaban y poseían, repunta a finales del s. xv (lám. 6), a pesar de la turbulencia política y religiosa de la época. Es como si la enorme inversión de dinero en estos objetos santos les proporcionase a sus dueños algún tipo de salvaguarda espiritual. and gold and fine gems. And for this reason, he added, it has always been helpful for learned scholars to be wealthy so as to be able to own their own books and not have to borrow them. And so too, he writes with somewhat sharper derision, the wealthy patrons of his day even believe that merely “possessing these books is sufficient as self-glorification, and they think that storing them in their treasure-chests is the same as preserving them in their minds” (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 21). Duran himself does not believe this, but because he was unable to deny the social power of these aristocrats, he nonetheless concedes that there is still “merit for their actions, since in some way they cause the Torah to be magnified and exalted; and even if they are not worthy of it, they bequeath a blessing to their children and those who come after them” (Friedländer and Kohn 1865, 21). Therein lies the Bible’s real artifactual power. It can even help those who do not deserve it! Duran clearly knew that the luxurious Bibles owned by these rich aristocrats—the only persons in Iberian Jewish society of the time with the financial means to pay for such Temple-like Bibles—were “trophy-books,” commissioned specifically for ostentatiously displaying their owner’s wealth. Many of the Bibles on display in this exhibit were probably such objects of display and ostentation. Still, the spiritual profits from showing off should not be lightly dismissed. Somewhat paradoxically, as I have noted, the production of these books commissioned and owned by wealthy Jews appears to have spiked in the late fifteenth century (Fig. 6), despite the political and religious turbulence of the period. It is almost as though the sheer investment of wealth in such valuable objects of sanctity provided their owners with a kind of spiritual security-blanket. Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 73 74 Lám. 6 / Fig. 6. Biblia, s. xv. Bible, 14--. San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Real Biblioteca, G‒II‒8, f. 24r. © Patrimonio Nacional. 01.Biblia Sefarad (Stern) :Maquetación 1 27/02/12 17:29 Página 75 Muchas de las características que he descrito como propias de la historia de la Biblia masorética en Sefarad se aplican también al ḥummash, o Pentateuco litúrgico. La característica más sobresaliente del Pentateuco litúrgico es la disposición global del mismo. En lugar de presentar el texto bíblico en su orden canónico, el Pentateuco litúrgico sigue la práctica sinagogal de leer la Torah en perícopas semanales de acuerdo con un ciclo anual, junto con las haftarot que acompañan a las lecturas del Pentateuco. Además, los volúmenes incluyen casi siempre los Cinco rollos que se leen con ocasión de las fiestas y los días de ayuno del calendario judío, e incluso a veces las secciones de «destino funesto» tomadas de los libros de Jeremías y Job, que también se leían durante el ayuno de Tish‘ah be-’av. La inclusión de estos pasajes de la Escritura confirma que estos libros estaban destinados a un uso sinagogal, o en relación con el servicio litúrgico, aunque se desconoce cómo se usaban dentro del espacio de la sinagoga. Esta manera de organizar y presentar la Escritura no tenía precedentes en la tradición oriental de los códices masoréticos. El género del ḥummash parece haberse originado en Ashkenaz, y tiene su paralelo en distintos tipos de libros bíblicos que se empleaban en el occidente latino para ser leídos durante la misa, como los epistolarios con lecturas de Pablo y los Actos de los Apóstoles, evangeliarios con lecturas de los Evangelios y leccionarios de misa que contenían la lectura de las Epístolas y del Evangelio. No hay, sin embargo, pruebas de que existiese ninguna influencia entre estos libros judíos y cristianos. A los escribas judíos y cristianos se les pudo fácilmente ocurrir un tipo de libro similar para solucionar el mismo problema logístico de disponer de una biblia para uso litúrgico. Many of the features I have described until now as characterizing the history of the masoretic Bible in Sepharad are also true of the ḥummash or liturgical Pentateuch. The most prominent feature of this type of Bible is its overall organization. Rather than presenting the biblical text in its canonical order, the liturgical Pentateuch follows the synagogal practice of reading the Torah in weekly divisions in an annual cycle along with the haftarot accompanying the weekly Pentateuchal readings; the volumes also typically, although not always, include the Five Scrolls that are also read on various holidays and fast days in the Jewish calendar along with, at times, the sections of “doom” from the prophet Jeremiah and the book of Job, both of which were also read on the fast day of Tish‘a be-’av. The inclusion of these specific Scriptural portions are clear indications that these books were meant for use either inside or in close connection with the synagogue and its liturgical service although it is not absolutely clear how they were used within the synagogue’s four walls. This way of organizing and presenting Scripture has no precedent in the early Near Eastern tradition represented by the masoretic codices. The genre of the ḥummash appears to have originated in Ashkenaz, and it is paralleled in different types of Bible books that were developed in the Latin West for biblical readings during the Mass, such as epistolaries for readings from the Pauline and Catholic Epistles and Acts, evangelistaries for readings from the Gospels, and larger Mass lectionaries that contained both the Epistles and Gospel readings. There is, however, no evidence for any influence between the Christian and Jewish books. Christian and Jewish scribes could easily have come up with the similar types of books as obvious ways to solve the same logistical problem of having a Bible Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 75 76 El Pentateuco litúrgico sefardí datado más antiguo que se conserva se escribió en 1318 (oxford, Bodleian Library, ms. Kennicott 4), pero la mayor parte de los ejemplos de este género en Sefarad datan de finales del s. xIv y sobre todo del s. xv. Si bien es cierto que, en cuanto a sus contenidos y organización, son idénticos a los modelos askenazíes (pues incluyen parashiyyot semanales de la Torah, haftarot y rollos), muchos de los sefardíes también incluyen masora, reflejando sin duda con ello el destacado papel que esta tenía en las biblias de Sefarad. En muchos de estos códices la masora está escrita con el mismo tipo de diseño micrográfico geométrico que se encuentra en las biblias sefardíes masoréticas. La página del Pentatuco litúrgico que aparece en la lám. 7 (entrada cat. 45), y que incluye tanto las haftarot como los cinco rollos, constituye un ejemplo relativamente temprano de este tipo. Como se puede ver, la masora aparece escrita en una forma geométrica de manera algo primitiva. El texto que aparece en la página es el comienzo de Éxodo 15, el Canto del Mar Rojo, poema que según la ley rabínica se escribe con un tipo especial de disposición textual denominada ariyah al gabbe levanah (lit. medio ladrillo sobre ladrillos). El Targum no suele aparecer en los ḥummashim sefardíes con tanta frecuencia como aparece en los Pentateucos askenazíes, un hecho que parcialmente se puede deber a la costumbre que existía en las comunidades sefardíes de estudiar la Biblia con el Tafsīr de Saadiah Gaón. Esta práctica aparece recogida en el testamento que el gran traductor Judá ibn Tibbon (1120–ca. 1190) dejó a su hijo Samuel (que llegaría a ser un traductor tan reputado como su padre), en el cual le aconseja «leer cada semana la sección del Pentateuco en árabe. Esto te ayudará a mejorar tu vocabulario árabe y te será de ayuda al traducir, en el caso de que te interese traducir» (Abrahams David Stern convenient to use in their respective liturgical services. The earliest dated surviving Sephardic liturgical Pentateuch was composed in 1318 (oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Kennicott 4), but most examples of the genre in Sepharad come from the late fourteenth- and fifteenth-centuries. While their basic contents and organization are identical to their Ashkenazi counterpart—the weekly parashiyyot of the Torah, the haftarot , and the scrolls—many of the Sephardic examples also contain the masorah, reflecting no doubt the prominent position that the masorah held in all Bibles in Sepharad. In a number of these codices the masorah is written in the same kind of micrographic geometrical designs found in Sephardic masoretic Bibles. The page from the liturgical Pentateuch seen in Fig. 7 (cat. entry 45), which includes both the haftarot and the Five Scrolls, is a relatively early example of the type; as one can see, the masorah is written here in geometrical, albeit somewhat primitive patterns. The text on the page is the beginning of Exodus 15, the Song at the Sea, and in line with rabbinic law, the poem is laid out in the special stichography called ariyah al gabbe levanah (a half brick over a full brick). In comparison to Ashkenazi Pentateuchs, the Aramaic Targum was less frequently copied in Sephardic ḥummashim, a fact that may be partly explained by a preference in Sephardic communities to study the Bible with the Tafsīr of Saadiah Gaon. This practice is famously attested in the ethical will that the great translator Judah ibn Tibbon (1120‒ca. 1190) wrote to his son Samuel in which he admonished him, “Read every week the Pentateuchal section in Arabic. This will improve thine Arabic vocabulary, and will be of use in translating, if thou 77 Lám. 7 / Fig. 7. Biblia litúrgica, Toledo, s. xIII. Liturgical Bible, Toledo, 12--. Madrid, Biblioteca Nacional de España, MSS/5469, ff. 73v‒74r. © Biblioteca Nacional de España. 78 1926, 65–66). (véase traducción del Pentateuco al judeo-árabe en entrada cat. 5). Un siglo después, los sabios sefardíes empezaron a animar a sus comunidades a recitar a Rashi en lugar de recitar el Targum. Uno de los primeros en introducir esta sustitución fue el tosafista Asher ben Yeḥiel (ca. 1250–1327) que se trasladó de Alemania a Castilla en 1303. A Asher le sucedió su hijo Jacob, autor del importante código legal Arba turim [Cuatro columnas], quien estipuló que la lectura de Rashi se considerase equivalente a la lectura del Targum porque al igual que esta última también la primera «explicaba» el sentido de la Torah, es decir, la forma en la que los rabinos de época clásica la entendían. Parece ser que la preeminencia de Rashi se debía no tanto a su peshat (interpretación literal-contextual) como al hecho de que, en su mayor parte, transmitía la tradición rabínica de forma abreviada y en un estilo accesible. La adopción de su comentario en las biblias sefardíes es un claro testimonio del modo en que las convenciones askenazíes se introdujeron en Sefarad, y a la inversa. La mención de Rashi nos lleva al tercer tipo de biblia que los judíos usaron en Sefarad: la biblia de estudio. Como ya se ha señalado, este es un tipo de biblia que parece haberse producido con el fin de ser destinada al estudio. El género incluye códices con más de un comentario por página, así como otros en los que el comentario ocupa una posición tan destacada que es lógico pensar que tal biblia se produjo específicamente con el objeto de que se estudiase ese comentario. La historia de la biblia de estudio está estrechamente relacionada con la historia de la exégesis bíblica judía en la Edad Media. En Sefarad, el estudio de la Biblia ocupaba un lugar central en el curriculum intelectual y educativo judío, y su status era mucho menos ambiguo del que tenía en Ashkenaz, donde se daba prioridad al estudio del David Stern shouldst feel inclined to translate” (Abrahams 1926, 65‒66). (See cat. entry 5, Arabic translation of Pentateuch in Judaeo-Arabic). A century later, Sephardic sages began to encourage their communities to recite Rashi in place of the Targum. Among the first to introduce this substitution was the tosafist Asher ben Jeḥiel ( ca . 1250‒1327) who moved from Germany to Castile in 1303. Asher was followed by his son, Jacob, the author of the important early legal code, the Arba turim [Four Columns], who explicitly ruled that reading Rashi was equivalent to reading the Targum because it, too, “explained” the meaning of the Torah—that is, as the Rabbis understood it. It appears that Rashi’s pre-eminence was due less to his peshat (literalcontextual interpretation) than to the fact that, for the most part, he presented the abridged rabbinic tradition in an accessible, reader-friendly style. The adaption of his commentary in Sephardic Bibles is clear testimony to the way Ashkenazi conventions were able to penetrate Sepharad, a phenomenon that also happened in the opposite direction as well. The mention of Rashi brings us to the third type of Bible that Jews used in Sepharad, the study-Bible. As already noted, this type of Bible is one that seems to have been intentionally produced for study. The genre includes codices with more than one commentary on the page as well as those in which the commentary occupies so prominent a position that it is fair to assume that the Bible was produced specifically for studying that commentary. The history of the study-Bible is closely intertwined with the history of medieval Jewish biblical exegesis. In Sepharad, Bible study occupied a central position in the Jewish intellectual and educational curriculum, and possessed a state far less ambiguous than it did in Talmud. La tradición exegética sefardí era heredera de la incipiente tradición gramatical desarrollada por los masoretas, enriquecida más tarde por el contacto que los judíos del mundo islámico tuvieron con la ciencia filológica árabe y la filosofía islámica. Ambas disciplinas, filología y filosofía, fueron centrales en la lectura de la Biblia de toda una corriente que comenzó con Saadiah, gaón de Babilonia, y continuó con su sucesor Samuel ben Ḥofni, y de una forma más acentuada aún con gramáticos andalusíes como Yonah ibn Ŷanāḥ y exegetas formados en al-Andalus como Abraham ibn Ezra (1089–1164). La atención prestada al estudio de la Biblia como una disciplina esencial continuó en los reinos hispanos y zonas vecinas, como Provenza, con exegetas como Naḥmánides (Moisés ben Naḥmán, 1194–1270) y David Kimḥi (ca. 1160–ca. 1235). A pesar de las quejas sobre el declive del estudio de la Biblia de personalidades como Profiat Durán, se puede hablar de una historia de la exégesis bíblica que se desarrolla de forma continua en Sefarad hasta la Expulsión. A lo largo de todo ese periodo el Pentateuco siguió siendo el pilar fundamental de la educación, con los Profetas y los Escritos como materias más avanzadas de estudio. Proverbios, Job y Eclesiastés, se estudiaban de forma intensiva como tratados de ética, y así lo demuestran los muchos manuscritos que se han conservado de estos libros con comentarios en sus páginas. Los comentarios bíblicos producidos en Sefarad se escribían como ḥibburim (composiciones) independientes, y generalmente incluían introducciones programáticas y en ocasiones digresiones cuasi-ensayísticas sobre los problemas que suscitaba la interpretación del versículo. Frente a ello, la mayor parte de los comentarios que se escribían en Ashkenaz eran comentarios individuales al lemma bíblico, presentados de manera ordenada, versículo a versículo y capítulo a capítulo. Ashkenaz, where Talmud study was emphasized. Sephardic biblical exegesis was the heir of the nascent grammatical tradition pioneered by the masoretes and was further enriched by the exposure of Jews living within the Islamic orbit to the developing sciences of Arabic philology and Islamic philosophy. Both disciplines— philology and philosophy—came to inform the reading of the Bible by Jews as well in an approach that began already with the Babylonian gaon, Saadiah, and continued with his successor Samuel ben Ḥofni, and even more so, with later Andalusi Jewish grammarians like Jonah ibn Janāḥ and later exegetes, trained in al-Andalus, like Abraham ibn Ezra. The attention to Bible study as a primary discipline continued into the period of the Hispanic kingdoms, both in Iberia and in related areas like Provence, with such commentators as Naḥmanides (Moses ben Naḥman, 1194‒1270) and David Kimḥi (ca. 1160‒ ca. 1235). Despite the complaints of figures like Profiat Duran over the waning of Bible study, it is possible to speak of a continuous history of biblical commentary in Sepharad until the Expulsion. Throughout this period, the Pentateuch remained the main focus of education, while the Prophets and the Writings were considered subjects for more advanced study. Proverbs, Job, and Ecclesiastes in particular were studied intensively as ethical tracts, as evidenced by the number of manuscripts of these books with commentaries on their pages. Biblical commentaries produced in Sepharad were written as independent ḥibburim (literary compositions), and regularly included programmatic introductions and sometimes virtually essayistic explorations of problems raised by a verse. In Ashkenaz, in contrast, most commentaries were lemmatic, that is, recorded simply as individual comments, presented in the order Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 79 80 En ambos ámbitos, sin embargo, la mayor parte de estos comentarios bíblicos circulaba en libros separados o quntresim. La exposición incluye algunos de estos quntresim (entrada cat. 26, comentario de David Kimḥi a Isaías; entrada cat. 25, comentario de Naḥmánides a Job; entrada cat. 47, comentario de Rashi a la Biblia). Muchos de ellos eran códices modestos, sin ningún tipo de particularidad, en el que los comentarios se escribían generalmente con escritura hebrea semicursiva, también llamada letra rabínica, con los comentarios separados por el lemma, es decir, una palabra o expresión bíblica que servía para que el lector identificase el pasaje bíblico que se estaba comentando. El quntres más sobresaliente que aparece en la exposición es un comentario a Isaías y a Profetas Menores (lám. 8) del gran diplomático, filósofo y exegeta portugués Isaac Abravanel (Lisboa 1437–venecia 1508), partes del cual fueron probablemente copiadas por el propio Abravanel en 1499, poco después de haber sido expulsado de Castilla, y mientras vagaba en el exilio por Corfú y Apulia (entrada cat. 24). No sabemos con exactitud cómo se usaban estos quntresim, si se leían con un códice bíblico al lado, o si se usaban solos, dado que probablemente el estudiante conocía la Biblia de memoria, con los lemmata sirviendo como simples recordatorios del versículo. Los peligros de es8 Citado a partir de tudiar de esta manera eran lo bastanParís, Bibliothèque nationale de France, te conocidos para que el exegeta Yosef ms. héb. 164, en Kimḥi, padre de David, le recomenSimon 1993, 92; dase al lector tener siempre una covéase también la pia de la Torah enfrente, «para que cita de Judá ibn así todo estuviese en el lugar correcMosconi, en la to»8. En algún momento, sin embarmisma página del go, los copistas empezaron a copiar artículo de Simon. biblias con más de un comentario en la misma página. Es probable que este tipo de biblia de estudio apareciese por primera vez en el David Stern of chapters and verses, verse by verse. In both centers, however, biblical commentaries generally circulated in quntresim. The present exhibit includes a number of these quntresim (cat. entry 26, David Kimḥi on Isaiah; cat. entry 25, Naḥmanides on Job; and cat. entry 47, Rashi on the Bible). Many of these quntresim were generally modest if not undistinguished codices in which the commentaries were typically written in a semi-cursive, so-called rabbinic script, with their comments typically separated by a lemma, that is, a word or short phrase from the Bible that keyed the reader to the comment’s scriptural occasion. Probably the most remarkable quntres in this exhibit is a commentary on Isaiah and the Minor Prophets (Fig. 8) by the great Portuguese diplomat, philosopher and exegete Isaac Abravanel (Lisbon 1437‒venice 1508) sections of which may have been written by Abravanel himself in 1499, shortly after being expelled from Castile, and while he wandered as an exile in Corfu and Apulia (cat. entry 24). We do not know precisely how these quntresim were used, whether they were read alongside biblical codices or studied alone, the Bible presumably being known by heart by the student, and with the lemmata serv- 8 Cited from Paris, ing merely as verse-reminders. The Bibliothèque dangers of studying this way were national de apparently sufficiently well-known France, MS héb. that the twelfth- century exegete 184, in Simon from Narbonne, Joseph Kimḥi, the 1993, 92; see as father of David, had to warn his well the quote reader always to have a Torah in from Judah ibn front of him, “and then everything Mosconi cited on will be in the right place.”8 At some the same page of Simon’s article. point, however, scribes began to write Bibles with multiple commentaries on the same page. This type of study-Bible probably 81 Lám. 8 / Fig. 8. Isaac Abravanel, Comentario a Isaías y Profetas Menores, Corfú y Monópoli, 1499. Isaac Abravanel, Commentary on Isaiah and Minor Prophets, Corfu and Monopoli, 1499. San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Real Biblioteca, G‒I‒11, ff. 270v‒271r. © Patrimonio Nacional. 82 norte de Francia a comienzos del s. xIII, pero en los ss. xIv y xv la práctica se extendió a los reinos hispanos, Italia y Alemania. La lám. 9 (entrada cat. 27), que corresponde a una biblia que data del s. xv, es un ejemplo destacado en este sentido. Como se puede apreciar, el copista usó un formato de página que hoy se conoce como página talmúdica. De hecho, esta disposición de la página derivaba del formato de página de la Glosa, desarrollada entre los siglos xII y xIII por copistas cristianos para la Biblia cristiana con comentarios patrísticos, formato conocido como Glossa ordinaria, y fue adaptada por copistas judíos en textos canónicos, como la Biblia, que generalmente se estudiaban acompañados de comentarios. Naturalmente, el formato glosado, en el que el texto bíblico y los comentarios aparecían en la misma página, era muy apropiado para los estudiantes. Pero además de resultar conveniente, este formato de página tenía además un carácter transformador, pues cambiaba la propia naturaleza del estudio de la Biblia. Al situar el texto bíblico y el comentario en la misma página, el formato hizo que el estudiar la Biblia con el comentario pasase a ser normativo. Más aún, al tener el comentario en la misma página el estudioso de la Biblia ya no la leía de forma secuencial, como hasta entonces había hecho, sino verso a verso, con el comentario correspondiente, cuando existía. Así, el texto bíblico se atomizó en pequeñas unidades léxicas y semánticas que combinaban versículo e interpretación. De ese modo, como ha apuntado C. Sirat, la página glosada hizo que texto y comentario estuvieran continuamente contrapuestos y que, fruto de tal contraposición, se generalizase el hábito de leer siempre la Biblia con su comentario (Sirat 1997). La presencia de varios comentarios en la misma página también fomentó el estudio comparativo de los comentarios bíblicos. Este proceso trajo consigo la aparición de los supercomentarios, David Stern first emerged in northern France in the early thirteenth century, but by the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, had spread to the Hispanic kingdoms and Italy as well as Germany. Fig. 9 (cat. entry 27) is a remarkable example of such a Bible dating from the fifteenth century. As one can see, the scribe appropriated a page format that is best known today as that of the talmudic page. In fact, this page layout derived from the glossed page format developed by Christian scribes in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries for the Christian Bible with the collected patristic commentaries known as the Glossa ordinaria, and was then adapted by Jewish scribes for use in canonical texts like the Bible which were regularly studied with commentaries. The glossed format with the biblical text and commentaries on the same page was obviously a more convenient text for a student to have and use. But more than being convenient, the page-format was transformative. It changed the very nature of Bible-study. By placing the Bible with its commentary on the same page, the format made studying the Bible with a commentary normative. Furthermore, with the commentary on the page, the student was less likely to read the biblical text sequentially; rather, he now read it verse by verse with the commentary intervening wherever it existed. The biblical text was thus atomized into small lexical and semantic units that combined verse and exegesis. In this way, as C. Sirat has noted, the glossed page forced the text and commentary constantly to confront each other, and out of that confrontation, the very habit of always reading the Bible with commentary also became regularized (Sirat 1997). Multiple commentaries on the same page also encouraged comparative study of biblical commentaries. This process led as well to the composition of 83 Lám. 9 / Fig. 9. Biblia rabínica, s. xv. Rabbinic Bible, 14--. San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Real Biblioteca, G‒I‒5, f. 21r. © Patrimonio Nacional. 84 o comentarios a los comentarios, un género que comenzó a despuntar en Sefarad, donde aparecieron supercomentarios a los comentarios de exegetas como Abraham ibn Ezra. Generalmente, tales supercomentarios establecen comparaciones entre los exegetas. A pesar de lo cómodo que resultaba y de la importancia que tuvo el formato glosado, a los escribas no les resultaba fácil copiarlos a mano, y el número de manuscritos con este formato es relativamente pequeño en relación con otros tipos de biblias. Sin embargo, con la llegada de la imprenta, y sobre todo a partir de la publicación de la segunda Biblia rabínica (venecia 1523–1524), que desarrolló más aún el formato de la página glosada, este tipo de biblia se convirtió en la biblia judía de estudio por excelencia. El presente ensayo no pretende ser el trabajo definitivo sobre la historia de la Biblia hebrea en la Península Ibérica antes de la expulsión de la población judía en la última década del s. xv, ni sobre las distintas biblias que existieron en sus distintas comunidades. Para dar un último ejemplo, a finales del s. xv, en un taller al parecer dedicado a la producción de biblias y localizado en Lisboa, se hicieron un grupo de biblias de lujosa factura, incluyendo tanto biblias masoréticas como Pentateucos litúrgicos (Sed-Rajna 1970 y 1988). Estas biblias presentan un mismo tipo de elementos decorativos (páginas con un doble marco de motivos florales y arabescos, uso de pan de oro, y paneles muy adornados) que reflejan influencia italiana, flamenca y portuguesa. Es este uno de los grupos de biblias hebreas más lujosamente decoradas de cuantas existen. Al igual que las procedentes de la Castilla del s. xv, dan prueba de una explosión de creatividad en el momento mismo en que se avecinaba una de las mayores catástrofes de la historia medieval judía. Asimismo, las traducciones bíblicas también ocuparon un importante lugar en Sefarad. Como David Stern super-commentaries, commentaries upon commentaries, a genre that especially took off in Sepharad, with super-commentaries on commentaries of exegetes like Abraham ibn Ezra. Such super-commentaries regularly compare one commentator to another. For all its convenience and importance, however, the glossed format was not easy for scribes to produce by hand, and the number of manuscripts with this format is relatively small compared to the other types of Bibles. With printing, however, and specifically with the publication of the Second Rabbinic Bible (venice 1523‒1524), which further developed the glossed page format, this type of study-Bible became the definitive Jewish study-Bible. The survey I have just completed by no means exhausts the history of the Hebrew Bible in the Iberian Peninsula before the expulsion of its Jewish population in the 1490’s or the varieties of Bibles that existed in its various communities. To give one further example, in the late fifteenth century, a group of extraordinarily lavish Bibles—including both masoretic Bibles and liturgical Pentateuchs—were produced in Lisbon, Portugal, in an atelier apparently specializing in the production of such Bibles (Sed-Rajna 1970 and 1988). These Bibles share common decorative designs—double-framed pages with intricate floral and arabesque patterns, the use of much gold leaf, and highly embellished panels—that reflect Italian, Flemish, and Portuguese influence and are among the most lavish decorated Hebrew Bibles ever produced. Like their Castilian counterparts in the late fifteenth century, these Bibles testify to a burst of creativity at the very brink of one of the most catastrophic moments in medieval Jewish history. podemos ver, la traducción árabe de la Biblia de Saadiah Gaón se copió muchas veces de forma independiente (entrada cat. 5). A partir de la expulsión de los judíos de Castilla y Aragón en 1492, aparecen biblias hebreas con traducciones latinas, a veces en forma de traducciones interlineales (entrada cat. 8), con frecuencia con la ayuda de conversos judíos al cristianismo. Por último, se ha de hacer mención de uno de los libros más espectaculares de cuantos fueron producidos en la Península Ibérica, joya de la corona de esta exposición: la Biblia de Alba. En 1422, Don Luis de Guzmán, gran maestre de la orden de Calatrava, en un intento de fomentar el entendimiento y la tolerancia entre cristianos y judíos, encargó una traducción de la Biblia hebrea al castellano, con el comentario de los rabinos. La persona a la que Don Luis invitó para dirigir su proyecto fue Moisés Arragel, rabino de la comunidad judía de Maqueda, en la provincia de Toledo. Terminada en 1422, la Biblia de Alba, nombre que se le da en función de su actual propietaria, la Casa de Alba, es una de las traducciones completas más antiguas de la Biblia hebrea a una lengua vernácula en la Edad Media. Tal como han demostrado los especialistas, la traducción de Arragel está repleta de interpretaciones y traducciones judías. Aunque los artistas que hicieron las magníficas ilustraciones y decoraciones en la biblia parecen haber sido cristianos, es muy posible que Arragel dirigiese el trabajo artístico, de modo que con frecuencia las ilustraciones contienen motivos e imágenes sacadas del Midrás y de la tradición exegética judía. La Biblia de Alba, símbolo de reconciliación y esperanza, representa la consumación de la larga tradición de la cultura judía en la Península Ibérica que, a pesar de haberse visto con frecuencia desgarrada por conflictos religiosos y por la violencia, da prueba del enorme y continuo poder creativo del intercambio y la simbiosis cultural. In addition, Bibles in translation also occupied an important place in medieval Sepharad. As we have seen, the Arabic translation of the Bible by Saadiah Gaon was often copied in its own book (cat. entry 5), and after the expulsion of the Jews from Castile and Aragon in 1492, Hebrew Bibles with Latin translations, sometimes in the form of interlinear translations (cat. entry 8) were produced, often with the help of converted Jews to Christianity. Finally, there is one of the most spectacular books ever produced in Sepharad, and the crown jewel of this exhibition—the Alba Bible. In 1422, Don Luis de Guzmán, Grandmaster of the order of Calatrava, with the idea of building understanding and toleration between Christians and Jews, commissioned a translation of the Hebrew Bible into Castilian. The person whom Don Luis invited to direct this project was Moses Arragel, rabbi of the Jewish community of Maqueda in the province of Toledo. Completed in 1422, the Alba Bible, so called after the later owners of the book, the nobility of the House of Alba, is one of the earliest complete extant translations of the Hebrew Bible into the vernacular in the Middle Ages, and as scholars have shown, Arragel’s translation was infused with Jewish interpretations and traditions. Although the artists who provided the lavish illustrations and decorations in the book may have been Christians, the artistic work, it seems, was also directed by Arragel, and the illustrations often contain motifs and images drawn from Midrash and Jewish exegetical tradition. As a work of reconciliation and hope, the Alba Bible is a fitting consummation to a lengthy tradition of Jewish culture in Sepharad that, while often riven by religious conflict and violence, nonetheless testifies to the enduring productive power of cultural exchange and symbiosis. Una introducción a la historia de la Biblia hebrea en Sefarad | The Hebrew Bible in Sepharad: An Introduction 85