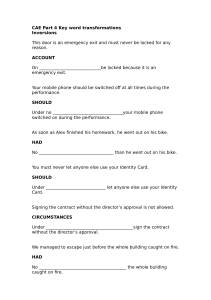

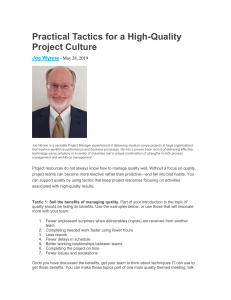

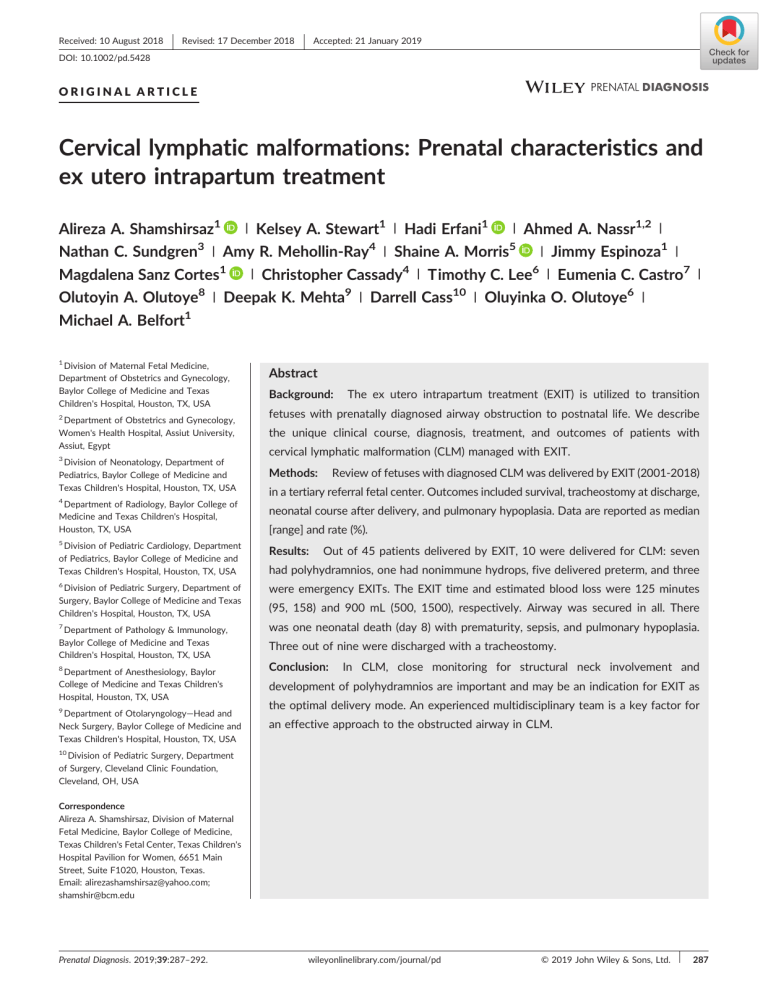

Received: 10 August 2018 Revised: 17 December 2018 Accepted: 21 January 2019 DOI: 10.1002/pd.5428 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Cervical lymphatic malformations: Prenatal characteristics and ex utero intrapartum treatment | Kelsey A. Stewart1 | Hadi Erfani1 | Ahmed A. Nassr1,2 | Alireza A. Shamshirsaz1 | Jimmy Espinoza1 Nathan C. Sundgren3 | Amy R. Mehollin‐Ray4 | Shaine A. Morris5 1 Cassady4 | | Christopher Magdalena Sanz Cortes Olutoyin A. Olutoye8 | Deepak K. Mehta9 Michael A. Belfort | Lee6 | | Timothy C. Eumenia C. Castro7 Darrell Cass10 | Oluyinka O. Olutoye6 | | 1 1 Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA 2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women's Health Hospital, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt 3 Division of Neonatology, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA Abstract Background: The ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) is utilized to transition fetuses with prenatally diagnosed airway obstruction to postnatal life. We describe the unique clinical course, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes of patients with cervical lymphatic malformation (CLM) managed with EXIT. Methods: Review of fetuses with diagnosed CLM was delivered by EXIT (2001‐2018) in a tertiary referral fetal center. Outcomes included survival, tracheostomy at discharge, 4 Department of Radiology, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA neonatal course after delivery, and pulmonary hypoplasia. Data are reported as median [range] and rate (%). 5 Division of Pediatric Cardiology, Department of Pediatrics, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA 6 Results: Out of 45 patients delivered by EXIT, 10 were delivered for CLM: seven had polyhydramnios, one had nonimmune hydrops, five delivered preterm, and three Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA were emergency EXITs. The EXIT time and estimated blood loss were 125 minutes 7 was one neonatal death (day 8) with prematurity, sepsis, and pulmonary hypoplasia. Department of Pathology & Immunology, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA 8 Department of Anesthesiology, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA 9 Department of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Baylor College of Medicine and Texas Children's Hospital, Houston, TX, USA (95, 158) and 900 mL (500, 1500), respectively. Airway was secured in all. There Three out of nine were discharged with a tracheostomy. Conclusion: In CLM, close monitoring for structural neck involvement and development of polyhydramnios are important and may be an indication for EXIT as the optimal delivery mode. An experienced multidisciplinary team is a key factor for an effective approach to the obstructed airway in CLM. 10 Division of Pediatric Surgery, Department of Surgery, Cleveland Clinic Foundation, Cleveland, OH, USA Correspondence Alireza A. Shamshirsaz, Division of Maternal Fetal Medicine, Baylor College of Medicine, Texas Children's Fetal Center, Texas Children's Hospital Pavilion for Women, 6651 Main Street, Suite F1020, Houston, Texas. Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Prenatal Diagnosis. 2019;39:287–292. wileyonlinelibrary.com/journal/pd © 2019 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 287 288 1 SHAMSHIRSAZ | ET AL. I N T RO D U CT I O N What's already known about this topic? Cervical lymphatic malformations are benign lymphatic malformations that are present in 1/20 000 births. Because of mass effect and invasion, they can indicate the use of ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT). EXIT has changed the outcome of fetuses diagnosed prenatally with an airway obstruction, including those with large neck masses (Figure 1).1-4 The need for EXIT is determined by the pres- • EXIT has changed the outcome of fetuses diagnosed prenatally with large neck masses. • Prenatal planning is essential for successful fetal and maternal outcomes in fetuses with lymphatic malformation ence of airway obstruction or severe tracheal deviation, as demonstrated by ultrasound and/or MRI.5,6 Lymphatic malformations (as opposed to other cervical masses such as teratomas) are less likely W h a t d o e s t hi s st u d y a d d ? to contain a significant vascular component or to compress surrounding structures but may cause deviation of the airway and can signif- • Structural neck involvement and development of icantly increase in size over gestation (Figure 2).7,8 The understanding polyhydramnios of these particular characteristics and their impact on outcomes after indication of EXIT. are important and may be an EXIT are important for operative planning and for prognosis. We • An experienced multidisciplinary team is crucial in the present here the clinical course, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes management of the obstructed fetal airway in cervical of patients with cervical lymphatic malformations managed with EXIT lymphatic malformation. at our center. FIGURE 1 MRI at 30w5d, including midline sagittal (a) and right parasagittal bSSFP (B) and axial SSFSE T2 images (C) showing an eccentrically located cystic LM, which partially encircles (black arrows) the cervical airway (white arrows). The LM does not invade the floor of the mouth FIGURE 2 MRI at 33w1d, including axial balanced steady state free precession (bSSFP, A) and sagittal single shot fast spin echo (SSFSE) T2 images (B) at the level of the cervical airway (white arrows), showing a large anterior cervical multiloculated cystic mass with retropharyngeal extension (black arrows) and invasion of the floor of the mouth (*) SHAMSHIRSAZ 2 289 ET AL. infant was diagnosed with a COL18A1 mutation (Knobloch syndrome; METHODS | a connective tissue disease) postnatally. 2.1 | EXIT Seven patients (70%) developed polyhydramnios at a median of EXIT procedure was performed by 33w1d [18w3d‐33w5d]. Amnioreduction was performed for three a multidisciplinary team including pediatric/fetal surgeons, fetal cardiologists, neonatologists, pediatric otolaryngologists and anesthesiologists, and operating room staff. EXIT is performed under maternal deep general anesthesia with continuous invasive blood pressure monitoring. Details of the procedure have been previously published.9,10 2.2 | patients. Only one fetus developed hydrops (at 29w4d). Table 1 shows the details of prenatal diagnostic parameters. The fetal airway was not visible at the final MRI in five patients (50%), and in four of these patients, there was invasion of the larynx or trachea by the lymphatic malformation. One patient had airway collapse by a hematoma caused by internal hemorrhage, which caused the tracheoesophageal deviation. Data collection IRB approval was obtained for a retrospective chart review of patients 3.2 | EXIT procedure with a prenatal diagnosis of cervical lymphatic malformation and subsequent EXIT at the Texas Children's Hospital (H‐37494). Between Information about the details of the EXIT procedure is presented in January 2001 and April 2018, we identified 10 cases of cervical lym- Table 1. All patients who delivered preterm (n = 5) had a history of phatic malformation out of the total of 45 EXIT procedures (22%). Data polyhydramnios. There were no cases of fetal decompensation prior and images were recovered from the electronic medical record and to delivery. The uterine incision was made in the lower segment in digital imaging systems at the Texas Children's Pavilion for Women. all except one patient who received upper segment hysterotomy due Retrospective measurements were made by trained physicians. to an anterior placental location. In this patient, the uterus was Parameters collected included obstetrical data and clinical course, prenatal images, diagnostic characterization of the lymphatic malformation, degree of airway involvement and resultant obstruction, oper- TABLE 1 Characteristics and obstetric outcomes in patients with EXIT for lymphatic malformationa ative and postoperative details, and neonatal outcome. Study subjects (N = 10) Primary neonatal outcomes included survival and tracheostomy at Variables discharge. Secondary outcomes included neonatal course after deliv- Maternal age, y ery, pulmonary hypoplasia (defined by first 24‐hr ventilator settings, or fraction of inspired oxygen greater than 30% at term corrected age and at least 7‐d postnatal age),11 subsequent treatment of lymphatic malformation and associated morbidities (requirement for gastrostomy tube, readmissions related to lymphatic malformation, need for physical or occupational therapy, and other complications). The Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development was used to 3 [1, 6] Parity 2 [0, 5] GA at diagnosis, wk and d 20w0d [16w0d‐21w1d] GA at presentation, wk and d 26w3d [20w1d, 34w0d] Male fetus 8 (80%) Prior cesarean delivery 0 Prenatal data evaluate the neurodevelopmental status. Data are reported using descriptive statistics. Continuous and categorical variables are reported as median [range] and rate (%), Floor of mouth involvement 7 (70%) Polyhydramnios 7 (70%) EXIT information respectively. Delivery Planned term (37‐38 w) 3 RESULTS | | Prenatal diagnosis and obstetrical course From January 2001 until April 2018, we evaluated 10 cases for cervical lymphatic malformation. All patients were monitored with repeated fetal ultrasounds until delivery. One patient had concurrent type 2 5 (50%) Preterm (36 w) 2 (20%) Preterm (emergency EXIT, 30‐34 w) 3 (30%) GA at EXIT, wk and d 3.1 30 [18, 37] Gravidity 36w5d [30w1d, 38w0d] Fetal exposure to anesthesia, min 99 [48, 100] Duration of EXIT, min 125 [95, 158] Estimated maternal blood loss, mL 900 [500, 1500] Maternal blood transfusion, (%) 2 (20%) Maternal post‐op length of hospital stay, d 4.5 [4, 10] vasa previa treated successfully at 24w4d weeks with fetoscopic laser ablation.12 Median estimated maternal blood loss during the proce- Abbreviation: EXIT, ex utero intrapartum treatment; GA, gestational age. a dure was 900 [500, 1500]; two out of 10 (20%) required blood transfusion. Of the 10 cases, all were singleton intrauterine pregnancies with a normal karyotype and no other structural malformations. One Fetal exposure to anesthesia was calculated as the time between maternal intubation and cord clamp. Duration of EXIT was calculated as the time between skin incision and procedure stop time. Values are presented as median [range] and n (%). 290 SHAMSHIRSAZ exteriorized and an external version to breech was performed. There were no significant maternal complications.13 3.3 | ET AL. TABLE 2 Neonatal outcomes in patients with EXIT for lymphatic malformationa Study subjects (N = 10) Variables Neonatal outcomes Neonatal treatment During the EXIT, satisfactory access to the airway was obtained in all Only surgical resection 2 (20%) cases. In one case, a large unilocular cyst within the cervical lymphatic Surgical resection plus sclerotherapy 3 (30%) malformation was drained prior to delivery. Treatment with Sirolimus 3 (30%) Surgery plus sclerotherapy plus Sirolimus treatment 1 (10%) No treatment (neonatal death) 1 (10%) There was a single neonatal death. This patient had PPROM at 29w3d and presented to the hospital 5 days later in active labor. The patient underwent an emergency EXIT at 30w1d, during which Number of surgical resections the fetus had bradycardia, underwent resuscitation, required tracheostomy with retrograde intubation, and was immediately placed in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) under high‐frequency oscillator ventilation. Despite intensive care, the infant expired secondary to sepsis and pulmonary hypoplasia at 8 days of age. Three infants were discharged home with a tracheostomy, two because the lymphatic malformation invaded oropharyngeal structures and one because of retropharyngeal deviation and facial edema. All three are still dependent on tracheostomy at the time of last evaluation (8 mo, 9 mo, and 3 y). Details of neonatal and pulmonary outcomes are reported in Table 2. 3.4 | Follow‐up One 4 (40%) Two 3 (30%) More than two 2 (20%) Airway successfully secured 10 (100%) Duration of intubation process, min 12 [5, 20] Time to extubation, d 34 [16,171] Length of stay in NICU, d 64 [9, 152] Tracheostomy 3 (33.3%) Pulmonary hypoplasia 2 (20%) Gastrostomy tube 7 (70%) Need for additional physical therapy 5 (50%) Intra‐mass bleeding 1 (10%) Obstructive sleep apnea 2 (20%) Conductive hearing loss 1 (10%) The median age at follow‐up was 2 years [4 mo‐14 y], and the time Surgical site infection/dehiscence 4 (40%) since last follow‐up was 2 years [4 mo‐6 y]. Of those not demonstrat- Neonatal death 1 (10%) ing normal developmental milestones, one had impaired gross motor skills and torticollis, and one had language delay (speaking five to eight Abbreviations: EXIT, ex utero intrapartum treatment; NICU, neonatal intensive care unit. words at 22 mo) with intact comprehension. Three children had subse- a Values are presented as median [range] and n (%). quent difficulties with speech or slurred speech. Tables 3–5 show the prenatal diagnosis, obstetrics, and neonatal outcomes on a case‐by‐case basis. TABLE 3 4 | DISCUSSION Case This study adds to the body of literature on reported outcomes of EXIT Diagnostic characteristics of the study subjects GA at EXIT Airway invasion Floor of mouth involvement Polyhydramnios Airway access B 33w3da ‐ ‐ Y 34w5da Y Y Yc L 3 38w0d ‐ ‐ ‐ NF 4 38w0d ‐ ‐ ‐ B 1 for cervical lymphatic malformations. We have previously reported the 2 fetal and maternal outcomes of the first 12 EXIT procedures done in our center and concluded the safety of the procedure for both mother b and child.14 The present case series addresses the diagnosis, course, 5 37w2d ‐ Y ‐ B treatment, and outcomes of 10 patients with cervical lymphatic mal- 6 36w0d ‐ Y Y B formation (from the total of 45 performed EXIT procedures). 7 30w1da Y Y Y R 8 37w1d Y Y Y B When compared with uncomplicated cesarean section, proportion of preterm deliveries was higher but maternal blood loss was in the 9 36w3d ‐ Y Y B normal accepted range.15 In the majority of cases, EXIT was completed 10 37w2d Y Y Y B using a low transverse uterine incision presumably enabling comparable outcomes with traditional cesarean section in future pregnancies. There were no significant complications postoperatively, and all Abbreviations: B, rigid bronchoscopy; EXIT, ex utero intrapartum treatment; GA, gestational age; L, direct laryngoscopy; NF, not found in medical record; R, retrograde intubation; Y, yes; (‐), no. women were discharged within 4 to 5 days. This supports the conten- a tion that EXIT is safe from a maternal perspective, with specific short‐ b term increased risk related only to the need for general anesthesia. c Emergency EXIT. Mother with fetoscopic repair for vasa previa. Fetus developed hydrops. SHAMSHIRSAZ TABLE 4 291 ET AL. Obstetrical outcomes in the study subjects Case GA at presentation Polyhydramnios Amnioreduction (number) GA at EXIT Emergency EXIT Maternal EBL, mL 1 32w4d Y ‐ 33w3d Y 900aa 3 34w5d Y 1500a b c 2 20w1d Y 3 34w0d N ‐ 38w0d NF 1200 4 26w3d N ‐ 38w0d N 500 5 22w1d N ‐ 37w2d N NF 6 23w2d Y ‐ 36w0d N 800 7 28w1d Y 2 30w1d Y NF 8 27w5d Y ‐ 37w1d N 750 9 26w1d Y 2 36w3d N 1000 10 31w3d Y ‐ 37w2d N 700 Abbreviations: EXIT, ex utero intrapartum treatment; GA, gestational age; N, no; NF, not found in medical record; Y, yes; (‐) indicates amniocentesis was not performed. a Required transfusion. b Mother with fetoscopic repair of vasa previa. c Fetus developed hydrops. TABLE 5 Neonatal outcomes of the study subjects Case GA at EXIT Survival Permanent trach Pulmonary hypoplasia Gastrostomy tube LOS Postdelivery 1 33w3da Y ‐ ‐ ‐ 38 2 34w5d Y Y ‐ Y 128 3 38w0d Y ‐ ‐ Y 152 4 38w0d Y ‐ ‐ Y 74 5 37w2d Y ‐ ‐ ‐ 9 6 36w0d Y ‐ ‐ Y 90 7 30w1da ‐ ‐ Y NF NF b a 8 37w1d Y ‐ Y Y 148 9 36w3d Y Y ‐ Y 34 10 37w2d Y Y ‐ Y 54 Abbreviations: EXIT, ex utero intrapartum treatment; GA, gestational age; LOS, length of stay; NF, not found; Y, yes; (‐), no. a Emergency EXIT. b Mother with fetoscopic repair for vasa previa. In our study, mortality was 10%, with 33% of our live patients outcome, the majority of infants did experience significant morbidity requiring permanent tracheostomy. In a previous study, Laje et al eval- from lymphatic malformations after delivery. Almost all infants had uated EXIT for delivery of babies with cervical lymphatic malformation subsequent gastroesophageal dysfunction, and 78% required a and reported a mortality of 23% and a 38% rate of children requiring a gastrostomy tube. Despite some speech delay and gross motor impair- permanent tracheostomy (median follow‐up = 11 y).16 In our study, a ment of the neck related to lymphatic malformation, the majority of combination of prenatal diagnostic imaging and clinical features were these children had normal milestones. Residual lymphatic malforma- observed more in those with poor outcomes, especially the need for tion, also, is not uncommon. Avoiding EXIT in cases where there is uncertainty as to the degree tracheostomy. The morbidity related to neurodevelopmental outcomes were of airway obstruction may be an option using an innovative approach. studied, and this information is important for counseling. Recently, After opening the abdomen, fetoscopic evaluation of the larynx and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), issued a warning on trachea can be performed, and if patency is confirmed, a routine cesar- the repeated or lengthy (greater than 3 hr) use of anesthetic and seda- ean section can be done without any further intervention.19 tion drugs, which may affect the later brain development. Although we There are several limitations to this study, the foremost being the never used more than 3 hours of anesthesia in our cohort, given the small sample size, which may affect the accuracy of the calculated possibility of repeated surgical procedures, it is recommended to dis- rates. Other limitations included the difficulty in obtaining retrospec- 17,18 cuss the risk/benefit in these cases. While the NICU length of stay tive data from the patient records, and this required imputation using was very variable and did not appear to be directly related to the population data for some measures. Additionally, there was variable 292 SHAMSHIRSAZ length of follow‐up, which made assessment of neurodevelopment and language/motor development more difficult. Cervical lymphatic malformations pose unique risks at the time of delivery and in the neonatal period. The addition of an experienced multidisciplinary team is a key factor for an effective approach to the obstructed fetal airway in cervical lymphatic malformation. This paper provides further information for parents to consider during counseling regarding the safety of EXIT procedure for mother and child versus the difficulties such children may experience later in life. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We are indebted to each of the study participants. Acknowledgments are also due to Mr Sohum C. Shah for participation in data gathering and members of the multidisciplinary team, Sundeep G. Keswani, MD; James Fisher, MD; and Carolyn A. Altman, MD, for their involvement in patient care and their contribution in design of the work, interpretation of the data, drafting, and critically reviewing the manuscript. AUTHORSHI P Each author has indicated that he or she has met the journal's requirements for authorship. FUND ING SOURCES This study was supported by the Baylor College of Medicine. CONF LICT S OF INTE R ES T None declared. ORCID Alireza A. Shamshirsaz Hadi Erfani https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6333-3177 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1655-6877 Shaine A. Morris https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8056-0934 Magdalena Sanz Cortes https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0265-9859 ET AL. 6. Teksam M, Ozyer U, McKinney A, Kirbas I. MR imaging and ultrasound of fetal cervical cystic lymphangioma: utility in antepartum treatment planning. Diagn Interv Radioly (Ankara, Turkey). 2005;11(2):87‐89. 7. Gaddikeri S, Vattoth S, Gaddikeri RS, et al. Congenital cystic neck masses: embryology and imaging appearances, with clinicopathological correlation. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2014;43(2):55‐67. 8. Farrell PT. Prenatal diagnosis and intrapartum management of neck masses causing airway obstruction. Paediatr Anaesth. 2004;14(1): 48‐52. 9. Garcia PJ, Olutoye OO, Ivey RT, Olutoye OA. Case scenario: anesthesia for maternal‐fetal surgery: the ex utero intrapartum therapy (EXIT) procedure. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(6):1446‐1452. 10. Olutoye OO, Olutoye OA. EXIT procedure for fetal neck masses. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24(3):386‐393. 11. Hedrick HL, Flake AW, Crombleholme TM, et al. The ex utero intrapartum therapy procedure for high‐risk fetal lung lesions. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(6):1038‐1043. discussion 44 12. Hosseinzadeh P, Shamshirsaz AA, Cass DL, et al. Fetoscopic laser ablation of vasa previa in pregnancy complicated by giant fetal cervical lymphatic malformation. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;46(4): 507‐508. 13. Erfani H, Nassr AA, Espinoza J, Lee TC, Shamshirsaz AA. A novel approach to ex‐utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) in a case with complete anterior placenta. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;228:335‐336. 14. Lazar DA, Olutoye OO, Moise KJ Jr, et al. Ex‐utero intrapartum treatment procedure for giant neck masses—fetal and maternal outcomes. J Pediatr Surg. 2011;46(5):817‐822. 15. Noah MM, Norton ME, Sandberg P, Esakoff T, Farrell J, Albanese CT. Short‐term maternal outcomes that are associated with the EXIT procedure, as compared with cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(4):773‐777. 16. Laje P, Peranteau WH, Hedrick HL, et al. Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) in the management of cervical lymphatic malformation. J Pediatr Surg. 2015;50(2):311‐314. 17. Olutoye OA, Baker BW, Belfort MA, Olutoye OO. Food and Drug Administration warning on anesthesia and brain development: implications for obstetric and fetal surgery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218(1):98‐102. 1. de Serres LM, Sie KC, Richardson MA. Lymphatic malformations of the head and neck. A proposal for staging. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121(5):577‐582. 18. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA review results in new warnings about using general anesthetics and sedation drugs in young children and pregnant women: United States Food and Drug Administration.; [cited 2018 June 21, 2018]. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/ Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532356.htm. 2. Liechty KW, Crombleholme TM, Flake AW, et al. Intrapartum airway management for giant fetal neck masses: the EXIT (ex utero intrapartum treatment) procedure. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(4): 870‐874. 19. Shamshirsaz AA, Nassr AA, Erfani H, et al. Fetoscopic laryngo‐ tracheoscopy: a novel diagnostic modality to avoid unnecessary ex‐utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) in cases with suspected fetal airway compromise. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2018. RE FE R ENC E S 3. Shamshirsaz AA, Belfort MA, Ball R. Fetal surgery. In: Apuzzio J, Vintzileos AM, Iffy L, eds. Operative Obstetrics. 4th ed. USA: Taylor & Francis; 2016:163‐179. 4. Marwan A, Crombleholme TM. The EXIT procedure: principles, pitfalls, and progress. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2006;15(2):107‐115. 5. Lazar DA, Cassady CI, Olutoye OO, et al. Tracheoesophageal displacement index and predictors of airway obstruction for fetuses with neck masses. J Pediatr Surg. 2012;47(1):46‐50. How to cite this article: Shamshirsaz AA, Stewart KA, Erfani H, et al. Cervical lymphatic malformations: Prenatal characteristics and ex utero intrapartum treatment. Prenatal Diagnosis. 2019;39:287–292. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.5428