VAN HOEK, M. 2016. El Arpa en el Arte Rupestre Andino. In: TRACCE - on-line Rock Art Bulletin.

Anuncio

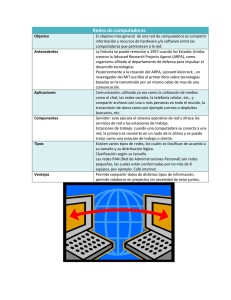

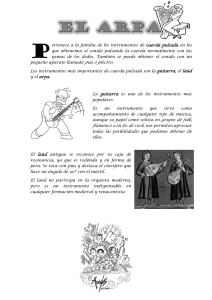

TRACCE - Online Rock Art Bulletin March 2016 - May 2016 Haga Clic aqui (Ctrl+clic) para leer la versión Inglés Click the link above to read the English version El Arpa en el Arte Rupestre Andino Maarten van Hoek - [email protected] Si se desea, es posible escuchar música de arpa de los Andes haciendo clic en este dibujo: If you wish, you can listen to Andean harp music by clicking on the figure below: Introducción En general es bastante raro encontrar imágenes de instrumentos musicales en el arte rupestre. Lo más comúnmente representados son tipos de instrumentos de viento, especialmente flautas u objetos que parecen ser flautas en el arte rupestre América del Norte y América del Sur. Imágenes de instrumentos de cuerda como violines y guitarras son aún más excepcional y representaciones de las liras y/o arpas están casi ausentes en el arte rupestre mundial. En este documento se describen tres (quizas cuatro) petroglifos de arpas que se han grabado en una pared en el Desierto de Atacama de América del Sur. Sorprendentemente, hasta ahora parecen representar las únicas imágenes de arpas en el arte rupestre en esta parte del mundo. La Historia del Arpa en el Arte Rupestre Una vez en la prehistoria alguien descubrió que el cuerda de un arco - cuando desplumado era capaz de producir un sonido específico que estaba relacionado con las propiedades combinadas de la cuerda y el arco. Por lo tanto, es comúnmente aceptado que el arpa y todos los demás instrumentos de cuerda relacionados originaron a partir del arco. Imagenes de arpas son muy antiguos. Una figura biomórfica pintada en una cueva llamada la ‘Grotte des Trois Maarten van Hoek - 2016 1 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Frères’, Ariège, Francia, se dice que representa la primera representación de un arpista (la fecha de esta pintura rupestre es de alrededor de 15.000 años antes de Cristo), pero me parece que la interpretación de dos simples líneas unidas ‘sostenido’ por el biomorfo es demasiado ambiguo. Sin embargo es un hecho que el arpa y el arpista son temas bastante común en el arte del antiguo Egipto. Parece ser, por ejemplo, esculpido en las paredes de los templos egipcios, como Karnak (Figura 1), que data de 2065 a 1785 B.C.. Las pinturas en las paredes de antiguas tumbas egipcias que datan desde el año 3000 aC mostran un instrumento que se asemeja mucho al arco de un cazador, sin embargo sin el columna que nos encontramos en arpas modernas. Otros personas afirman que el primer ejemplo de una verdadera arpa se encuentra como un grabado de línea fina en una de las muchas piso-piedras decoradas en Tell el-Mutesellim (Mediggo) en el Valle de Jezreel en el norte de Israel (Braun 2002: 59, Fig. II.6). Esos grabados Mediggo se cree que datan de alrededor de 3300 a 3000 B.C.. Figura 1. Bajo relieve en piedra caliza (que data del Imperio Medio) cerca de la Capilla Blanca de Karnak, Luxor, Egipto. Fotografía © de Maarten van Hoek. Aunque en muchas partes del mundo personas tocan el arpa, las representaciones inequívocas del arpa en el arte rupestre son extremadamente raras. Sin embargo, algunos ejemplos han sido registrados. Lo que parecía ser un arpa greco-romano (Rao 1986: 51) se encontró en una pintura rupestre en Nimbubhoj, Pachmarhi, India central, donde una persona delgada (probablemente un hombre, aunque también las mujeres han representado tocando el arpa en la India también) parece estar sentado y tocando un arpa con una caja de resonancia cuadrada (Figura 2.A). La hilera de puntos se cierne sobre la caja puede representar los sonidos emergentes. Petroglifos de arpa - dice que datan de alrededor del año 2000 aC - también se ha registrado en el Desierto de Negev en Israel (Braun 2002: 73-74; Fig. III.1a). David Coulson fotografió una pequeña arpista que está pintado en una pared de roca en la Meseta de Ennedi en Chad, en el corazón del Sahara (Figura 2.B). Jorge de Torres (2015) observó que sólo muy pocos (cinco!) representaciones de arpistas hasta el momento se han registrado en el arte rupestre del Sahara y, además, que se encuentran concentrados en una zona bastante pequeña (Ennedi) y parecen estar ausente en el resto del Desierto del Sahara. Polly Schaafsma (1997: Fig. 12) incluye un dibujo de un violín y un arpa pintado en líneas negras finas en una pared de una cueva llamada Las Cuevas de las Monas (Chih-2), Chihuahua, en el norte de México (Figura 2.C ). Hasta el momento - y por lo que yo sé - el ejemplo en Chihuahua fue la única representación de un arpa registrado en el arte rupestre de las Américas. Sin embargo, un sitio de arte rupestre en el Desierto de Atacama en América del Sur demostró para contener tres petroglifos posthispano que son inequívocas de arpas y un ejemplo dudoso. Lo más probable es que esos tres (o cuatro) petroglifos de arpas son únicos. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 2 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figura 2. A: Pintura de la roca en Nimbubhoj, Pachmarhi, India. Basado en una fotografía en Nagaraja Rao 1986: Lámina 42. B: Pintura rupestre en Ennedi, Chad. Basado en una fotografía de David Coulson 1996; TARA. C: Pintura rupestre en el Las Cuevas de las Monas, Chihuahua, México. Basado un dibujo de Polly Schaafsma 1997: fig. 12. Todos los dibujos de Maarten van Hoek. Descripción del Sitio Aproximadamente 70 km desde el Océano Pacífico, en un río coriente NE-SO, que ha tallada un valle en en los depósitos volcánicos más suaves, hay un extenso sitio de arte rupestre. Como parte del Desierto de Atacama, el desierto más seco del mundo, casi nunca llueve en esta área, y la agricultura en este estrecho valle principalmente depende del agua de escorrentía desde los Andes. En un punto en el valle que tiene una altitud de 1880 m, y en el lado norte se encuentra un abanico aluvial triangular con una pendiente empinada en la zona de pie cortada por el río. El abanico fue construido por un río (mayormente seco) (quebrada seca) que se ejecuta a la SE a través de un estrecho abismo (Figura 3). A unos 80 m NW del fondo del abanico a ambos lados de la quebrada seca y cerca la zona de cabecera del abanico son dos grandes paredes, gran parte de afloramiento fragmentadas de un tipo de roca más duro y de color marrón-rojizo. Casi todos los paneles de la pared occidental, así como varios bloques (colapsos), contienen petroglifos. El panel que es el foco en este trabajo se encuentra en el lado occidental de la quebrada (marcado ‘1’ en las Figuras 3 y 4) a una altitud de aproximadamente 1907 m (todas las altitudes y distancias en este documento se basan en Google Earth). Panel 1 también se encuentra a unos 1070 m SSE de la llanta de la Pampa Alta, que se ubica a 2282 m. Los nombres del lugar y del valle no serán revelados aquí con el fin de proteger las imágenes de arpa únicas. Figura 3. Localización de Panel 1 con los petroglifos de arpa. Dibujo © de Maarten van Hoek, basado en Google Earth. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 3 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figura 4. Localización de Panel 1 con los petroglifos de arpa, mirando al NO desde el lado opuesto del valle. Las flechas amarilla y azules: quebrada y río. Dibujo © de Maarten Van Hoek, basado en una fotografía de R. M. Cuesta. Descripción del Panel 1 Panel 1 es parte de la gran pared de roca en el lado oeste del abanico y está situado muy cerca de la zona de cabecera del abanico (Figura 5). El panel casi vertical mira al Nor-Este y se encuentra en la base de una afloramiento grande, de la que la parte superior tiene una cavidad grande y - por encima de que - algunos petroglifos, incluyendo un pájaro. El panel fracturado y parcialmente desmenuzado cubre un plano de aproximadamente 2.5 metros de alto por 2 m de ancho. Panel 1 (Figura 6) contiene petroglifos de diferentes épocas, incluyendo bioformas y símbolos solares obviamente desde la época precolombina y algunos petroglifos que claramente son del período posthispano. Este último grupo incluye una gran estrella de cinco puntas (pentágrama) que apunta hacia abajo y (hay un petroglifo similar en Cabracancha, Bolivia), lo más importante, las imágenes de arpas. Debido a las varias fases de la actividad rupestre y la erosión en especialmente la parte inferior del panel (probablemente por abrasión eólica), varias imágenes son visible solamente con dificultad. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 4 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figura 5. Localización de Panel 1 en la afloramiento occidental. Zona enmarcada: ubicación de los petroglifos de arpa. Dibujo © de Maarten Van Hoek, basado en una fotografía de R. M. Cuesta. g: algunos otros paneles con arte rupestre. Figura 6. Panel 1, que muestra los tres petroglifos de arpa A, B y C. P: Pentágrama. D: Posible arpa. Dibujo © de Maarten van Hoek, basado en una fotografía de R. M. Cuesta. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 5 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Los Petroglifos de los Arpas Por lo general el arte rupestre Andino del período posthispanica contiene imágenes de jinetes (Van Hoek 2013), iglesias, escenas de batalla con armas de fuego y - sobre todo - cruces, ya sea aisladas o cruces de calvario. Los instrumentos musicales son excepcionalmente raros en el arte rupestre posthispano y incluso los instrumentos musicales en el arte rupestre prehispano son escasos y principalmente comprenden instrumentos de viento (Van Hoek 2005) y (posiblemente) los tambores. Además, imágenes de ‘flautistas’ son a menudo bastante ambigua (Van Hoek 2010). Por lo tanto, es una sorpresa encontrar imágenes inequívocas de arpas en un farellón de roca en el Desierto de Atacama. Hay un total de cuatro imágenes de un arpa triangular en el Panel 1, denominados A, B, C y D en la Figura 6. Todos los petroglifos, incluyendo las cuerdas, han sido picoteado (con una roca más dura), aunque no hubiera habido ningún problema para tallar en especial las cuerdas en la roca volcánica bastante suave. Por debajo de una grieta hay una hilera de dos figuras antropomórficas tocandas el arpa (A y B) y abajo de arpa A, arpa D. A la izquierda y por encima de la misma grieta hay una imagen aislada de solo un arpa (C). Arp C (Figura 7) ha sido superpuesto sobre un petroglifo Pre-Colombino de un zoomorfo (probablemente un camélido). A su izquierda parece estar conectado a un par de líneas rectas que pueden formar parte de la composición. El arpista está claramente ausente en esta composición. Sólo algunas de las cuerdas del arpa son visibles. Arpa D (Figura 6) es dudosa y sin arpista. Figura 7. Petroglifo de arpa C en Panel. Dibujo © de Maarten van Hoek, basado en una fotografía de R. M. Cuesta. Arpa B (Figura 8) cuenta con un arpista indistinta a la derecha del instrumento. El arpista parece estar sentado en una pequeña silla (S en Figura 8). Las cuerdas de esto arpa sólo son visibles en la parte superior, como la parte inferior del Panel 1 (incluyendo partes de la caja de resonancia) son deteriorado por la intemperie. Lo más importante es que desde la consola del arpa emerge una cabeza zoomorfa más distintiva. Es más probable que representa la cabeza de un ave (un cóndor, tal vez?). Maarten van Hoek - 2016 6 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figura 8. Petroglifos de arpas A y B en el Panel 1. Dibujo © de Maarten van Hoek, basado en una fotografía de R. M. Cuesta. S: Silla. El arpa A (Figura 8) es el conjunto mejor conservado. El arpa tiene una forma claramente triangular y también la caja de resonancia está perfectamente indicado. Desde la consola emerge una cabeza zoomorfa; más claramente ornitomorfo (un cóndor?). Se enfrenta a otro apéndice - menos claramente zoomorfo - en el lado opuesto del clavija - en la parte superior de la columna. Las cuerdas son claramente visibles, aunque parte de las cuerdas se ha superpuesto por un gran área picoteado, más o menos circular. Elementos circulares similares se encuentran a la derecha de el arpista (ver Figuras 6 y 8). Un elemento puede ocultar parte de su brazo, mientras que otros elementos se han superpuesto en la silla - que es todavía claramente visible - sobre el que se asienta el arpista. Sus pies (zapatos?) y las piernas dobladas son claramente visibles. También la cabeza del arpista A es muy clara. Se encuentra frente al observador y cuenta con una boca y dos ojos que están conectados al contorno de la cabeza. Se lleva claramente un sombrero de copa abombada que es típico de los trajes posthispano. Petroglifos de figuras antropomórficas que llevan los sombreros similares ocurren en Santa Bárbara (Río Loa, Chile) e incluyen una hilera de camélidos conducidas por tres personas y una persona aparentemente montando un camélido (Berenguer, 1999: 47). Se han reportado representaciones de jinetes con sombreros de ‘copa y ala’, por ejemplo, en Chirapaca, Bolivia (Taboada Téllez 1992; Arenas Campos 2011: la figura 32.a). Por lo tanto, es posible que - al igual que con la flauta andina - sólo los hombres se les permite tocar el arpa en el período hispano (temprano). Además Arenas Campos señala que ‘La representación de sombreros abombados en las representaciones rupestres ha venido siendo interpretada como un icono de autoridad social en el nuevo contexto de dominación colonial’ (2011: 147). Por lo tanto, el arpista ‘A’ puede representar una persona de importancia también. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 7 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Discusión En primer lugar, hay que destacar que cuatro imágenes de arpas aparecen en un panel en un valle remoto en el áspero Desierto de Atacama. El valle está, además, muy poco poblada; menos de 1300 personas viven en toda la zona. Además, no hay grandes ciudades o aldeas en el valle y la ciudad más grande cercana está ubicada a 200 km. Sólo una carretera conduce en el valle. Por otra parte, el pueblo más grande en el valle - de sólo 400 habitantes - se ubica a 13 km NE desde el sitio de arte rupestre. Cerca del sitio hay pequeñas chacras. Es obvio que la zona nunca adquirió alguna importancia y siguió siendo un distrito Aymara durante todo el período colonial, como el área de tierras agrícolas adecuadas más bien limitado nunca atraído suficientes colonizadores españoles. Sin embargo, cuatro petroglifos de arpas y dos arpistas se han registrado en este valle. Esas imágenes deben ser de la época posthispana. El arpa - y posiblemente todos los demás instrumentos de cuerda - eran desconocidos para los Aymaras indígenas antes de la conquista española de América del Sur. Está claro que el arpa fue introducida en América del Sur, muy probablemente por los misioneros jesuitas. En el Desierto de Atacama esto probablemente ocurrió después 1600 dC y los registros más antiguos de una capilla católica en el valle - que data de 1613 dC - parecen confirmar esto. Por lo tanto, es casi seguro que los petroglifos de los cuatro arpas datan de después de 1600 dC. Sin embargo, los petroglifos de los arpas definitivamente no son recientes. Los petroglifos son bastante deteriorados y patinados y indican que las imágenes datan del período hispano (temprano). Además, ciertamente no son ejemplos de graffitis reciente; son petroglifos reales. Aunque que sin duda las gentes indígenas de América del Sur estaban fascinados con el instrumento, hizo cambios en él y lo adoptó como parte de sus propias culturas, es cierto que en este valle remoto el arpa nunca se convirtió en un instrumento de uso común. En ceremonias locales, fiestas y rituales se tocan principalmente grandes flautas, trompetas, tambores grandes utilizado por los varones, antaras (flautas de pan) y a veces todavía se tocan guitarras. Sin embargo, hay festividades que incluyen el arpa, como el Wayñu, un género musical y danza popular andino originario a la época colonial, especialmente en el Perú. Algunos elementos de la Wayñu se originan en la música de los Andes Precolombino, especialmente en el área del antiguo Imperio Inca. El Wayñu todavía se practica, también por las gentes Aymaras. Por lo tanto, posiblemente los cuatro petroglifos de arpa se relacionan de un festival Wayñu, que se llevó a cabo algún día en algún lugar del Desierto de Atacama, posiblemente en el propio valle. Es notable que no había - hasta ahora - ningún registro de esas cuatro petroglifos de arpa. Ellos son tan únicas que cualquier investigador inmediatamente habría mencionado el descubrimiento de los petroglifos en una publicación. Sin embargo, en lo que yo pueda verificar, publicaciones sobre el arte rupestre de la época colonial en los Andes (por ejemplo Hostnig 2007; Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008; Arenas Campos 2011; González Jiménez 2014) no describen o mencionan o no se refieren a las imágenes de arpas en el Desierto de Atacama desierto (o más allá). Incluso una publicación que trata específicamente del arte rupestre colonial de esta parte del Desierto de Atacama no menciona los arpas (esta publicación no se especifica aquí con el fin de no revelar la ubicación del sitio). Esto es lo más extraño porque el sitio donde se encuentran los petroglifos de los arpas también tiene un petroglifo posthispano de un antropomorfo que llevaba un sombrero (con cruz latina en la parte superior) y al menos dos petroglifos posthispanos muy claros de barcos; no las pequeñas Maarten van Hoek - 2016 8 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino balsas que son bastante comunes en el arte rupestre prehispana del Desierto de Atacama, pero grandes barcos a vela con mástiles, posiblemente españolas, que son - por cierto - también excepcionalmente raros en el arte rupestre del Desierto de Atacama (Berenguer, 1999: 49; Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008: 233; 255; Parte V - Fig. 19). Por último, uno de los elementos de dos de los petroglifos de arpa es tan evidente que se requiere una explicación adicional. Tanto arpa A como arpa B tienen un cabeza de un pájaro muy claro que emerge desde la consola. Esto puede indicar que los cuatro arpas no se han utilizado con fines religiosos en el que - en el contexto de América del Sur en general - la forma y el uso de arpas fueron muy restringidos de acuerdo a las normas oficiales. Es más probable que los arpas fueron utilizados en un contexto popular en que el arpa evolucionó rápidamente de acuerdo a la estética de los constructores de arpa u arpistas. Muchas veces esta autonomía es más evidente en la decoración del arpa en que cabezas esculpidas de felinos y / o aves (a menudo opuestos) son más sobresalientes. Incluso hasta la fecha arpas ya sea con una sola cabeza de ave o con dos cabezas opuestas existen y se reproducen en los Andes. Conclusión En un remoto valle del Desierto de Atacama extremadamente seco, un panel de roca demostró que soportar tres (quizas cuatro) petroglifos inequívocos de arpas posthispanos, dos de los cuales son tocados - silenciosamente - por arpistas. El conjunto más visible comprende un arpa (A) con una cabeza de un pájaro en la parte superior, mientras que el arpista lleva un sombrero colonial de copa abombada. Aunque en tiempos prehistóricos también las mujeres definitivamente tocaban el arpa - por ejemplo en el antiguo Egipto - lo más probable es que los dos petroglifos de arpistas en el Desierto de Atacama representan los varones, posiblemente involucrados en alguna fiesta, por ejemplo el Wayñu. Es cierto que esos cuatro petroglifos de arpas son únicos y deben ser protegidos para el futuro. Agradecimientos y fuentes y fuentes Agradezco a Dennis Slifer por su ayuda en la búsqueda de instrumentos musicales en el arte rupestre de América del Norte. Los dibujos de las Figuras 4 a 8 son basados en fotografías hechas por R. M. Cuesta (el nombre completo del autor no está mencionado aquí, con el fin de evitar la búsqueda en el Internet para encontrar la ubicación del sitio). El mapa de la Figura 3 se basa en Google Earth (2013). Traducido con Google Translate TRACCE (ISSN 2281-972X) Online Rock Rock Art Bulletin è edito dalla Cooperativa Archeologica Le Orme dell'Uomo, anche indicata come Footsteps of Man e che ha sede in Valcamonica (piazza Donatori di Sangue 1, Cerveno, BS - I). TRACCE (ISSN 2281-972X), an Italian word for “Tracks", since 1996 is the first online Rock Art Bulletin. It is maintained by Footsteps of Man archaeological society (Valcamonica - I). Maarten van Hoek - 2016 9 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino TRACCE - Online Rock Art Bulletin March 2016 - May 2016 The Harp in Andean Rock Art Maarten van Hoek - [email protected] Introduction In general it is rather rare to find musical instruments depicted in rock art. Most commonly depicted are all sorts of wind instruments, especially flutes or flute-like objects in the rock art of North and South America. Images of string-instruments like violins and guitars are even more exceptional and depictions of lyres and/or harps are almost absent in global rock art. This paper describes three (perhaps four) petroglyphs of harps that have been recorded on a rock wall in the Atacama Desert of South America. Surprisingly, up to now they seem to represent the only rock art images of harps in this part of the world. The History of the Harp in Rock Art One time in prehistory someone discovered that the cord of a bow - when plucked -was able to produce a specific sound that was related to the combined properties of the cord and the bow. Therefore, it is commonly accepted that the harp and all other related string-instruments originated from the bow. Images of harps are very old. A biomorphic figure painted in a cave named the ‘Grotte des Trois Frères’, Ariège, France, is said to represent the earliest depiction of a harp-player (the rock painting dates from around 15000 B.C.), but I find the interpretation of the two simple joined lines ‘held’ by the biomorph too ambiguous. It is a fact however that the harp and the harp-player are rather common themes in ancient Egyptian art. It appears for instance sculptured on the walls of Egyptian temples, like Karnak (Figure 1), which dates from 2065 to1785 B.C.. Paintings on the walls of ancient Egyptian tombs dating from as early as 3000 B.C. show an instrument that closely resembles the hunter's bow, without, however, the pillar that we find in modern harps. Others claim that the very first illustration of a true harp is found as a fine-line etching on one of the many decorated floor-stones at Tell elMutesellim (Megiddo) in the Valley of Jezreel in northern Israel (Braun 2002: 59, Fig. II.6). Those Megiddo etchings are thought to date from around 3300 to 3000 B.C.. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 10 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figure 1. Limestone bas-relief (dating from the Middle Kingdom) near the White Chapel of Karnak, Luxor, Egypt. Photograph © by Maarten van Hoek. Although in many parts of the world people play the harp, unambiguous representations of the harp in rock art are extremely rare. Yet, some examples have been recorded. What appeared to be a Graeco-Roman harp (Rao 1986: 51) was found in a rock painting at Nimbubhoj, Pachmarhi, Central India, where a slender person (probably a man, although also females have been depicted to play the harp in India as well) seems to be seated and playing a harp with a square soundbox (Figure 2.A). The row of dots hovering over the box may represent the sounds emerging. Harp-like petroglyphs - said to date from around 2000 B.C. - have also been reported from the Negev Desert in Israel (Braun 2002: 73-74; Fig. III.1a). David Coulson photographed a small harp-player that is painted on a rock wall on the Ennedi Plateau in Chad, in the heart of the Sahara (Figure 2.B). Jorge de Torres (2015) remarked that only very few (five!) representations of harp-players have so far been recorded in Saharan rock art and moreover that they are found concentrated in a rather small area (the Ennedi Plateau) and seem to be absent in the rest of the Sahara Desert. Polly Schaafsma (1997: Fig. 12) included a drawing of a violin and harp painted in thin black lines on a wall of a cave called Las Cuevas de las Monas (Chih-2), Chihuahua, in northern Mexico (Figure 2.C). So far - and as far as I know - the Chihuahua example was the only depiction of a harp recorded in the rock art of the Americas. However, one rock art site in the Atacama Desert of South America proved to house three unambiguous petroglyphs of Post-Columbian harps and one doubtful one. Most likely those three (or four) harp petroglyphs are unique. Figure 2. A: Rock painting at Nimbubhoj, Pachmarhi, India. Based on a photograph in Nagaraja Rao 1986: Plate 42. B: Rock painting of the Ennedi Plateau, Chad. Based on a photograph by David Coulson 1996; TARA. C: Rock painting at the Las Cuevas de las Monas, Chihuahua, Mexico. Based on a drawing by Polly Schaafsma 1997: Fig. 12. All drawings by Maarten van Hoek. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 11 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Site Description About 70 km inland from the Pacific Ocean, in a NE-SW running river, which has cut a gorge-like valley in the rather soft volcanic deposits, is an extensive rock art site. Being part of the Atacama, the driest desert on earth, it hardly ever rains in this area and agriculture in the narrow valley mainly relies on run-off water from the High Andes. At a point where the valley floor has an altitude of about 1880 m and on the north side is a triangular alluvial fan with a steeper scarp where cut by the river. The fan was built by a (mostly dry) river (quebrada) that runs to the SE through a narrow chasm (Figure 3). At about 80 m NW of the valley floor on both sides of the quebrada and near the apex of the fan are two large, much fragmented outcrop walls of a harder type of red-brown rock. Almost every panel of the western wall, as well as several (detached) boulders, bears petroglyphs. The panel that is the focus in this paper is found on the western side of the quebrada (marked ‘1’ in Figures 3 and 4) at an altitude of about 1907 m (all altitudes and distances in this paper are based on Google Earth). Panel 1 is also located about 1070 m SSE of the rim of the High Pampa, which is at 2282 m. The names of the site and of the valley will not be revealed here in order to protect the unique harp images. Figure 3. Location of Panel 1 with the harp petroglyphs. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on Google Earth. Figure 4. Location of Panel 1 with the harp petroglyphs, looking NW from the opposite side of the valley. Yellow and blue arrows: stream and river. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by R. M. Cuesta. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 12 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Description of Panel 1 Panel 1 is part of the large rock wall on the west side of the alluvial fan and is located rather near the apex of the fan (Figure 5). The almost vertical panel faces NE and is found at the base of a large outcrop part, of which the upper part has a large cavity and - above that - some petroglyphs, including a bird. The fractured and partially flaked panel measures approximately 2.5 meters in height and 2 m in width. Panel 1 (Figure 6) is covered with petroglyphs from different eras, including biomorphs and solar symbols obviously from the Pre-Columbian Period and a few petroglyphs that clearly are from the Post-Columbian Period. This latter group includes a large downward pointing pentagram (there is a similar petroglyph at Cabracancha, Bolivia) and, most importantly, the images of harps. Because of the several layers of petroglyph production and the weathering of especially the lower part of the panel (probably by eolian abrasion), several images are only visible with difficulty. Figure 5. Location of Panel 1 on the western outcrop wall. Framed area: location of the harp petroglyphs. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by R. M. Cuesta. g: some other rock art panels. The Harp Petroglyphs Post-Columbian rock art of the Andes usually comprises images of horsemen (Van Hoek 2013), churches, gun-fights and - above all - crosses, either isolated or on altars. Musical instruments are exceptionally rare in Post-Columbian rock art and even Pre-Columbian images of musical instruments are scarce and mainly comprise wind-instruments (Van Hoek 2005) and (possibly) drums. Moreover, images of ‘flute-players’ are often rather ambiguous (Van Hoek 2010). It is therefore a surprise to find unambiguous images of harps on a rock wall in the Atacama Desert. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 13 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figure 6. Panel 1 showing the three harp petroglyphs A, B and C. P: Pentagram. D: Possible harp. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by Mrs. Cuesta (see acknowledgements). There are altogether four images of a triangular harp on Panel 1, which have been labelled A, B, C and D in Figure 6. All petroglyphs, including the strings, have been pecked (with a harder type of rock), although it would not have been any problem to incise especially the string-elements in the rather soft volcanic rock. Below a crack is a row of two anthropomorphic figures that are playing the harp (A and B) and, below harp A, harp D. To the left and above the same crack is the isolated image of just a harp (C). Harp C (Figure 7) has been superimposed upon a Pre-Columbian petroglyph of a zoomorph (probably a camelid). To its left it seems to be connected to a few straight lines that may be part of the composition. The harp-player is clearly absent in this composition. Only some of the strings of the harp are visible. Harp D (Figure 6) is somewhat doubtful and without a harpist. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 14 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Figure 7. Harp petroglyph C on Panel 1. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by R. M. Cuesta. Harp B (Figure 8) features an indistinct harp-player to the right of the instrument. The harpplayer seems to be seated on a small stool (S in Figure 8). The strings of this harp are only visible in the upper part, as the lower part of Panel 1 (including parts of the soundbox) is weathered. Most importantly, from the shoulder of the harp a most distinct zoomorph head emerges. It most probably depicts a bird’s head (a condor perhaps?). Figure 8. Harp petroglyphs A and B on Panel 1. Drawing by Maarten van Hoek, based on a photograph by R. M. Cuesta. S: Stool. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 15 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Harp A (Figure 8) is the best preserved ensemble. The harp has a clearly triangular shape and also the soundbox is perfectly developed. From the shoulder emerges a zoomorphic head; again clearly ornitomorphic (a condor?). It faces another appendage - less clearly zoomorphic - on the opposite side of the neck - on top of the pillar. The strings are clearly visible, although part of the strings has been superimposed by a large - roughly circular - pecked element. Similar circular elements are found to the right of the harp-player (see Figures 6 and 8). One element may hide part of his arm, while other elements have been superimposed upon the still clearly visible stool upon which the harp-player is seated. His feet (shoes?) and curved legs are clearly visible. Also the head of the harp-player A is remarkably clear. It faces the observer and features a mouth and two eyes that are connected to the outline of the head. It clearly wears a widebrimmed, outlined hat that is typical for Post-Columbian outfits. Petroglyphs of anthropomorphic figures wearing similar hats occur at Santa Barbara (Río Loa, Chile) and include three persons herding camelids and one apparently riding a camelid (Berenguer 1999: 47). Representations of horsemen with dome-shaped hats have been reported, for instance at Chirapaca, Bolivia (Taboada Téllez 1992; Arenas Campos 2011: Fig. 32.a). It is therefore possible that - like with the Andean flute - only males were allowed to play the harp in (early) colonial times. Arenas Campos moreover remarks that ‘La representación de sombreros abombados en las representaciones rupestres ha venido siendo interpretada como un icono de autoridad social en el nuevo contexto de dominación colonial’ (2011: 147). The harpplayer may therefore represent an important person as well. Discussion First of all, it is remarkable that four images of harps occur on one panel in a remote valley in the harsh Atacama Desert. The valley is moreover very sparsely populated; less than 1300 people live in the whole area. Also, there are no major towns or villages in the valley and the nearest large town is 200 km away. Only one road leads into the valley. Moreover, the largest village in the valley - of only 400 inhabitants - is found 13 km NE of the rock art site. Near the site are small farm buildings. It is obvious that the area never acquired any importance and remained an Aymara district throughout the Colonial Period, as the rather limited area of suitable agricultural land never attracted sufficient Spanish settlers. Yet, four petroglyphs of harps and two harp-players have been recorded in this valley. Those images must be Post-Columbian. The harp - and possibly all other string-instruments - were unknown to the indigenous Aymara people before the Spanish Conquest of South America. It is clear that the harp was introduced to South America, most likely by Jesuit missionaries. In the Atacama this probably happened after A.D. 1600 and the oldest records of a Catholic chapel in the valley - dating from A.D. 1613 - seem to confirm this. Therefore it is almost certain that the petroglyphs of the four harps date from after A.D. 1600. Yet, the harp petroglyphs are definitely not recent. The petroglyphs are rather weathered and patinated and indicate that the images date from the (early) Colonial Period. Moreover, they certainly are not examples of recent graffiti; they are real petroglyphs. Although the indigenous peoples in South America no doubt were fascinated with the instrument, made changes to it and adopted it as part of their own cultures, it is certain that in this remote valley the harp never became a commonly used instrument. In local ceremonies, festivities and rituals, mainly flutes, trumpets, large tambourines used by men, antaras (panflutes) and sometimes guitars are still played. Maarten van Hoek - 2016 16 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Yet there are festivities that include the harp, like the Wayñu, a genre of popular Andean music and dance dating back to the Colonial Period, especially in Peru. Some elements of the Wayñu originate in the music of the Pre-Columbian Andes, especially in the area of the former Inca Empire. The Wayñu is still practiced, also by Aymara peoples. Thus, possibly the four harp petroglyphs relate of a Wayñu festival, held some day somewhere in the Atacama, possibly in the valley itself. It is remarkable that there was - so far - no record of those four harp petroglyphs. They are so unique that any researcher would immediately have mentioned the discovery of the petroglyphs in a publication. Yet, as far as I could check, publications dealing with rock art from the Post-Columbian Period in the Andes (for instance Hostnig 2007; Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008; Arenas Campos 2011; González Jiménez 2014) do not describe or mention or refer to images of harps in the Atacama Desert (or beyond). Even a publication specifically dealing with the colonial rock art of this part of the Atacama does not mention the harps (this publication is not specified here in order not to reveal the location of the site). This is the more strange as the site where the harp petroglyphs are found also has a Post-Columbian petroglyph of an anthropomorph wearing a hat (with Latin cross on top) and at least two very clear Post-Columbian petroglyphs of ships; not the small rafts that are rather common in the ancient rock art of the Atacama, but large, possibly Spanish sailing ships with masts that are by the way - also exceptionally rare in the rock art of the Atacama (Berenguer 1999: 49; Aguayo Sepúlveda 2008: 233; 255; Parte V - Fig. 19). Finally, one element of two of harp petroglyphs is so conspicuous that it needs further explanation. Both harp A and harp B have a very clear bird-head emerging from the shoulder. This may indicate that all four harps have not been used for religious purposes in which - in general South American context - the shape and use of harps were much restricted according to official standards. It is more likely that the harps were used in a popular context in which they could rapidly evolve according to the aesthetics of the harp builders/players. This autonomy is often most obvious in the decoration of the harp, in which the (often opposing) carved heads of felines and/or birds are most eye-catching. Even today harps with either a single bird-head or with two opposing heads exist and are played in the Andes. Conclusion In a remote valley of the extremely dry Atacama Desert a rock panel proved to bear three (perhaps four) unambiguous Post-Columbian petroglyphs of harps, two of which are played silently - by harp-players. The most conspicuous ensemble comprises a harp (A) with a birdhead on top, while the harp-player is wearing a wide-brimmed colonial hat. Although in prehistoric times also women definitely played the harp - for example in ancient Egypt - it is most likely that the two petroglyphs of harp-players in the Atacama Desert represent males, possibly involved in some festivity, like the Wayñu. It is certain that those four harp petroglyphs are unique and must be protected for the future. Acknowledgements and sources I am grateful to Dennis Slifer for his assistance in searching for musical instruments in North American rock art. The drawings of Figures 4 to 8 are based on photographs made by R. M. Cuesta (the full name of the author is not provided here, in order to prevent searching the internet for the site location). The map of Figure 3 is based on Google Earth (2013). Maarten van Hoek - 2016 17 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino Referencias - References Aguayo Sepúlveda, E. E. 2008. Símbolos y Sacralidad en el Arte Rupestre de la Provincia del Loa: del siglo X al XXI. Memoria para optar al título de Arqueólogo. Universidad de Chile. Arenas Campos, M. A. 2011. Representaciones Rupestres en los Andes Coloniales. Un Mirada al Sitio Rupestre Toro Muerto (Comuna de la Higuera, IV Región de Coquimbo - Chile). Tesis para optar al título de antropológo. Universidad Academia. Santiago de Chile. Braun, J. 2002. Music in Ancient Israel/Palestine: Archaeological, Written and Comparative Sources. Eerdmans. Berenguer, J. 1999. El Evanescente Lenguaje del Arte Rupestre en los Andes Atacameños. In: Arte Rupestre en los Andes de Capricornio. Eds. José Berenguer and Francisco Gallardo. M.Ch.A.P. Santiago de Chile. De Torres, J. 2015. Instruments of community: lyres, harps and society in ancient north-east Africa. The British Museum Blog, London. González Jiménez, B. 2014. Discurso en el paisaje Andino Colonial: reflexiones en torno a la distribución de sitios con arte rupestre colonial en Tarapacá. Diálogo Andino. Vol. 44; pp. 75 - 87. Hostnig, R. 2007. Arte rupestre post-colombino en una provincia alta del Cusco, Perú. In: Rupestreweb, Rao, N. 1986. Indian Archaeology; 1983-84, a review. New Dehli, India. Taboada Téllez, F. 1992. El Arte Rupestre Indígena de Chirapaca, Depto. de La Paz, Bolivia. In: Arte rupestre colonial y republicano de Boliovia y paises vecinos. Contribuciones al Estudio del Arte Rupestre Sudamericano . Editor: Roy Quejerazu Lewis. SIARB, Vol. 3; pp. 111 - 167. La Paz, Bolivia. Van Hoek, M. 2010. Mogollon Rock Art and the Status of the ‘Flute Player’. In: Proceedings of the XV world congress UISPP. Lisbon. BAR International Series. Vol. 2108; pp. 161 - 173. Archaeopress, Oxford, England. Van Hoek, M. 2005. Biomorphs ‘playing a wind instrument’ in Andean rock art. Rock Art Research. Vol. 22-1; pp. 23 - 34. Melbourne, Australia. Van Hoek, M. 2013. The Horseman of Alto de Pitis, Peru: A Post-Columbian Outsider in a Pre-Columbian Landscape. Andean Rock Art Paper 1. Oisterwijk, the Netherlands. * TRACCE (ISSN 2281-972X) Online Rock Rock Art Bulletin è edito dalla Cooperativa Archeologica Le Orme dell'Uomo, anche indicata come Footsteps of Man e che ha sede in Valcamonica (piazza Donatori di Sangue 1, Cerveno, BS - I). TRACCE (ISSN 2281-972X), an Italian word for “Tracks", since 1996 is the first online Rock Art Bulletin. It is maintained by Footsteps of Man archaeological society (Valcamonica - I). Maarten van Hoek - 2016 18 TRACCE: El Arpa Andino