- Ninguna Categoria

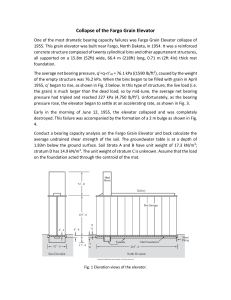

Manufacturing Engineering & Technology Textbook

Anuncio