Modulating-the-Flavor-Profile-of-Coffee-One-Roaster-s-Manifesto

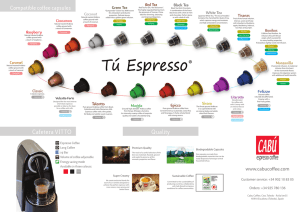

Anuncio