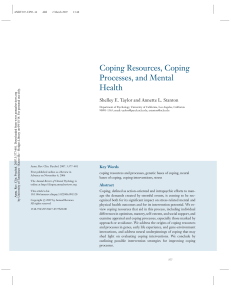

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/271536919 Familial Impact and Coping with Child Heart Disease: A Systematic Review Article in Pediatric Cardiology · January 2015 DOI: 10.1007/s00246-015-1121-9 · Source: PubMed CITATIONS READS 40 276 5 authors, including: Alun Jackson Erica Frydenberg Australian Centre for Heart Health University of Melbourne 151 PUBLICATIONS 2,018 CITATIONS 143 PUBLICATIONS 2,883 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Rachel P-T Liang Rosemary Olive Higgins University of Melbourne Heart Research Centre 22 PUBLICATIONS 80 CITATIONS 53 PUBLICATIONS 741 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Heart Kids View project Posttraumatic growth after a cardiac event View project All content following this page was uploaded by Erica Frydenberg on 03 February 2016. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. SEE PROFILE Familial Impact and Coping with Child Heart Disease: A Systematic Review Alun C. Jackson, Erica Frydenberg, Rachel P.-T. Liang, Rosemary O. Higgins & Barbara M. Murphy Pediatric Cardiology ISSN 0172-0643 Pediatr Cardiol DOI 10.1007/s00246-015-1121-9 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Science +Business Media New York. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be selfarchived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol DOI 10.1007/s00246-015-1121-9 REVIEW ARTICLE Familial Impact and Coping with Child Heart Disease: A Systematic Review Alun C. Jackson • Erica Frydenberg • Rachel P.-T. Liang • Rosemary O. Higgins Barbara M. Murphy • Received: 13 July 2014 / Accepted: 16 January 2015 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 A. C. Jackson (&) R. P.-T. Liang R. O. Higgins B. M. Murphy Heart Research Centre, 14-20 Blackwood Street, North Melbourne, VIC 3051, Australia e-mail: [email protected] enhance family coping. Twenty-five studies were selected for inclusion, using the PRISMA guidelines. Thematic analysis identified a number of themes including psychological distress and well-being, gender differences in parental coping, and variable parenting practices and a number of subthemes. There is general agreement in the literature that families who have fewer psychosocial resources and lower levels of support may be at risk of higher psychological distress and lower well-being over time, for both parent and the child. Moreover, familial factors such as cohesiveness and adaptive parental coping strategies are necessary for successful parental adaptation to CHD in their child. The experiences, needs and ways of coping in families of children with CHD are diverse and multi-faceted. A holistic approach to early psychosocial intervention should target improved adaptive coping and enhanced productive parenting practices in this population. This should lay a strong foundation for these families to successfully cope with future uncertainties and challenges at various phases in the trajectory of the child’s condition. A. C. Jackson E. Frydenberg R. P.-T. Liang Melbourne Graduate School of Education, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia Keywords Child heart disease Familial impact Parenting Coping Social support A. C. Jackson Centre on Behavioural Health, University of Hong Kong, 2/F The Hong Kong Jockey Club Building for Interdisciplinary Research, 5 Sassoon Road, Pokfulam, Hong Kong Introduction Abstract Families of children with congenital heart disease (CHD) cope differently depending on individual and familial factors beyond the severity of the child’s condition. Recent research has shifted from an emphasis on the psychopathology of family functioning to a focus on the resilience of families in coping with the challenges presented by a young child’s condition. The increasing number of studies on the relationship between psychological adaptation, parental coping and parenting practices and quality of life in families of children with CHD necessitates an in-depth re-exploration. The present study reviews published literature in this area over the past 25 years to generate evidence to inform clinical practice, particularly to better target parent and family interventions designed to R. O. Higgins Department of Physiotherapy, Faculty of Medicine, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia B. M. Murphy Faculty of Medicine, School of Psychological Sciences, Dentistry and Health Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC 3010, Australia Several studies have reported that the presence of chronic conditions in children places the well-being of the entire family at risk as the burden of care increases vulnerability to major psychological and social disturbances [25, 40, 61]. Diagnosis is recognised as a particular point of vulnerability [54, 56]. Graetz et al. [20] note the range of new familial adjustment tasks post-diagnosis, whilst others [51] go further in identifying diagnosis, the commencement of 123 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol treatment, transition from hospital to home and relapse as all being potential points of elevated stress, even in families who are otherwise coping well, which is the majority of families [50]. Two decades of research into family coping with childhood illness, including behavioural issues [16], has seen a welcome shift away from the psychopathology of family functioning to a focus on family resilience in coping with the challenges associated with their child’s illness [30, 34]. Coping has been defined [35] as the ability to understand the meaning of the illness and its treatment; manage emotional reactions and continue to undertake necessary actions; fulfil responsibilities; and provide support. Coping also refers to the process of managing stressful demands [23]. The majority of studies on families’ response to childhood conditions suggest that overall, most families adjust well [31, 35, 36, 51]. However, a significant subset of parents of children with CHD (PCCHD) has difficulty coping in the short and long term [21, 35, 36]. Parental coping has been demonstrated to be a significant predictor of coping and adjustment in children with conditions including epilepsy [47], sickle cell disease [59] and childhood leukaemia [35, 36, 48]. PCCHD are not always able to make the best use of informational, practical and emotional support provided at the point of diagnosis or at the site of ongoing treatment. They often express a need for time and space to process emotions such as grief, fear and loss and to assimilate the new situation into their repertoire of existing coping patterns as well as learning enhanced coping skills [26–28]. These emotional, well-being and coping enhancement needs have been recognised as relevant to child heart disease families at various phases of the child’s illness trajectory [22, 52, 58]. For example, acute stress disorder in parents after their infant’s cardiac surgery has been identified [15], as have issues in paternal attachment to their infant at the time of surgery [4]. The purpose of this systematic review was to examine evidence of how child heart disease families are impacted by the challenges presented by a young child’s condition, in order to better target parent and family interventions designed to enhance the coping capacity of these families. Method Procedure Multi-database Boolean searches were conducted in EBSCOhost, CSA Illumina and JSTOR using the search term ‘family coping’ AND ‘child heart disease’. The database search was limited to English-language scholarly articles of peer-reviewed journals published from January 1990 onwards. The top 225 results were selected by relevance 123 from the 53,506 populated results and imported into EndNote X7. An initial sort of the titles and abstracts resulted in 82 articles being rejected as either they were duplicates or there was no full-text report available. An additional 42 studies were identified from manual searches of the reference lists of key studies identified. The resulting 185 articles were subjected to detailed assessment based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria: Sample Studies were considered for the current review if they met the following inclusion criteria: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. The study sample comprised families with dependent children aged under 21 years with clearly identified congenital heart disease (CHD) (not acquired) No comorbidity or other presenting chronic illness in the study group although these may be present in control groups Studies focused on the familial impact of child heart disease and family coping and impact on, and coping by, parents of children with CHD (PCCHD) Explicit methodological design (qualitative, quantitative and/or observational) with clear measurement instruments and study design reported Full-text report was available in English. Studies were excluded if: 1. 2. 3. The articles were reviews, editorials or commentaries They either comprised a single case study or had a sample size \10 They were not deemed relevant to the primary focus on the association between child heart disease and family coping. Data Extraction Two authors independently evaluated and extracted the data. The accuracy of extraction of each study was assessed against the original document by a third author. The following data were extracted from included studies: (a) study characteristics, including authors, date, the jurisdiction where data were collected, characteristics of the children and sample size; (b) method, including measurement instruments, data sources and study design; (c) statistical analysis employed; and (d) statistical data related to the association between child heart disease and family coping. Results The review covers 25 studies with about half from European countries (N = 13) and the other half from the USA Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol and Canada (N = 9) and one each from Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Israel. All studies were conducted with families of children with various forms of congenital heart disease (CHD), ranging from mild to severe. Some studies included comparison groups of families of children with other minor illness and/or healthy children, whilst other studies compared families of children with mild CHD to those with more complex or severe CHD. A PRISMA flow diagram [44] shows the selection of papers for inclusion and exclusion (Fig. 1) [42]. A majority of the studies employed quantitative measures (N = 17) with the use of control or comparison groups. Four qualitative studies involved an exploratory inquiry using semi-structured interviews and four utilised both quantitative and qualitative methods. All quantitative studies used at least one validated tool to measure various factors pertaining to the familial impact of children with CHD on parents. Details of studies examined are presented in Table 1. Discussion Following a thematic analysis of the many factors that the 25 studies examined in relation to familial impact of child heart disease and family coping, three major themes (along with subthemes) were identified: Fig. 1 PRISMA flow diagram [44] of study selection process I. II. III. Impact on family: psychological distress and wellbeing; family functioning; quality of life Coping: Psychological functioning; gender and age differences Parenting: parenting stress; parenting practices/style; the role of attachment styles Impact on Family Psychological Distress and Well-being The main findings on mental health outcomes for parents of children with CHD (PCCHD) as compared to parents of healthy children or children with other diseases generally showed a higher incidence and severity of anger, anxiety, distress, depression, hopelessness and/or somatisation symptoms [11, 38, 39]. The severity of the child’s heart lesion at diagnosis was related to parental distress levels where PCCHD with more severe lesions showed higher levels of psychological distress [6]. Higher psychological distress was also associated with poorer understanding of the diagnosis and poorer cohesiveness in the family [13]. Gender differences were observed for PCCHD, with mothers reporting higher state anxiety [60], significantly more somatic symptoms [55] and greater prevalence of clinically significant psychological distress and hopelessness compared to fathers [13, 38]. Articles identified through multiple databases search (n = 53, 506) Articles screened by relevance (n = 225) Articles rejected at title/abstract or duplicates (n = 82) Additional records identified (n = 42) Full text articles retrieved for detailed evaluation (n = 143) Studies rejected (n = 160) with reasons: 1. 2. 3. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria 4. (n = 25) 5. Review or editorials (n = 11) Small sample size or single case studies (n=5) Sample does not include families with CHD patients under 14 (n =22) Sample with other chronic illness or conditions (n=25) Studies with other focuses such as impact of CHD on child rather than family, service provision, measurement tools or program evaluations (n =97) 123 Study Social impact on families of children with complex CHD Quality of life among PCCHD Mothers’ attachment style, their mental health, and their children’s emotional vulnerabilities: a 7-year study of children with CHD References Almesned et al. [1] Arafa et al. [2] 123 Berant et al. [3] Children with heart diseases (67.5 % CHD ? 32.5 % rheumatic heart disease) of mean age 73.2 months Children diagnosed with mild and severe forms of CHD during their first year of life N = 63 Mothers/Israel 20 children with simple CHD and 21 children with complex CHD managed in the univentricular tract N = 41/Saudi Arabia N = 400 ? 400 as comparison group (parents of children with minor illness)/Egypt Child’s characteristics Sample size/country T3 (7 years post-diagnosis)—MHI and marital satisfaction plus children’s reported self-concept and Children’s Apperception Test T2 (1 year post-diagnosis)—MHI and marital satisfaction (50-item ENRICH) T1 (diagnosis)—self-report attachment style and Mental Health Inventory (MHI) A 7-year longitudinal study with data collected on three occasions with various measures: Quantitative ? Qualitative SF-36 V1 to assess health-related quality of life (HRQL) on the domains of physical functioning, physical role, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, emotional role and mental health Structured questionnaire—sociodemographic characteristics, CHD-related data, family-related risk data; Quantitative Implications: Worthwhile considering the role of parental attachment in shaping children’s self-image and emotional wellbeing Mothers’ attachment insecurities (both anxiety and avoidance) at T1 were associated with their children’s increased emotional problems and poor selfimage 7 years later Parametric tests, including correlations and hierarchical regression analyses, revealed that maternal avoidant attachment at T1 was the best predictor of deterioration in the mothers’ mental health and marital satisfaction over the 7-year period, especially in a subgroup whose children had severe CHD Implications: Psychological status, social support and reassurance of the parents to address parental HRQOL should be considered when making treatment decision for their children Factors found to have a significant impact of HRQOL: severity of illness, type of heart disease, age of child, having multiple children, financial situation and presence of comorbid condition. For example, lowest mean scores for younger age, rheumatic heart disease and female children MANOVA results revealed that parents of children with heart diseases reported significantly poorer HRQOL compared with parents of children with minor illness, except for the pain subscale, with most significant differences on the domains of general health, vitality and physical role Two-sample t test analyses revealed that families of children with complex CHD who underwent univentricular tract repair had significantly higher IFS (61.3 vs. 52.0) mean scores than families with simple CHD, particularly in the domain of familial burden, followed by mastery, financial burden and personal strain Quantitative Cross-sectional survey using the 24-item Impact on Family Scale (IFS) administered to the two groups of families. The IFS has four subscales (on 4-point Likert scale) assessing perceived 1. financial burden; 2. familial/ social impact; 3. personal strain; and 4. mastery Key findings Method/measures Table 1 Details of studies that met the inclusion criteria for examining the relationship between congenital child heart disease and family impact and coping Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol Study Psychosocial outcomes for preschool children and families after surgery for complex CHD Psychological distress in PCCHD: the impact of prenatal versus post-natal diagnosis References Brosig et al. [5] Brosig et al. [6] Child’s characteristics Preschool-aged children (ages 3–6 years) with CHD, namely hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS; N = 13) and transposition of the great arteries (TGA; N = 13) Ten infants prenatally diagnosed and seven infants post-natally diagnosed with severe CHD Sample size/country N = 31 parents/USA N = 17 parents/USA The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)—completed at the time of diagnosis, at the time of birth and 6 months after birth. Prenatal and post-natal groups were compared to each other and to BSI norms Quantitative Psychometric test scores were compared to population norms using z scores Child Behaviour Checklist Parent Behaviour Checklist Parenting Stress Index IFS Paediatric quality of life inventory Implication: need to provide parents with psychological support, regardless of the timing of diagnosis. Parents of children with more severe lesions are at risk of higher levels of psychological distress, particularly over time The severity of the child’s heart lesion at diagnosis was related to parental distress levels; parents with children with more severe lesions had higher BSI scores (81 vs. 33 % with scores in the clinically significant range) Six months after birth, the post-natal group scores on the BSI did not differ from test norms, but the prenatal group scores remained significantly higher than test norms Results using independent-sample t tests revealed that both prenatal and post-natal groups did not differ significantly from each other on the BSI. Both groups’ BSI was significantly higher than test norms at the time of diagnosis Implications: Importance of the examination of parental stress, family functioning, and behavioural expectations for the child in the context of routine medical/cardiac follow-up Children with HLHS had higher rates of attention (23 vs. 0 %) and externalising behaviour problems (15 vs. 10 %) in the clinical range than children with TGA Parents of children with HLHS reported greater parenting stress and more negative impact of the child’s illness on the family than parents of children with TGA PCCHD were more permissive in their parenting style than parents of healthy controls Quality of life scores of PCCHD did not differ from those of healthy controls T tests and Mann–Whitney tests results revealed: Quantitative Parents completed the following measures: Key findings Method/measures Table 1 Details of studies that met the inclusion criteria for examining the relationship between congenital child heart disease and family impact and coping Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 123 Study Mothers’ lived experiences of support when living with young children with CHD Maternal factors related to parenting young children with congenital heart disease The Meaning of Cost for Families of Children With CHD References Bruce et al. [7] Carey et al. [8] Connor et al. [10] Table 1 continued Child’s characteristics Children of 3–12 years old diagnosed with CHD Children (aged 2–5 years) with moderate to severe CHD Children (aged 1 day to 5 years) with various degrees of CHD complexity, currently admitted for congenital heart surgery Sample size/country N = 10 mothers/Sweden 123 N = 30 ? 30 as control (all mothers)/USA N = 20 parents/USA Exploratory inquiry using semi-structured interviews (6 open-ended questions) focused on identifying the meaning of ‘cost’ as experienced by the parents and their perception of the social impact of these costs on the family Qualitative Home visit by researchers to collect information on family demographics, observation of parent–child interaction and responses to a qualitative semistructured interview focusing on parenting expectations, social support and help seeking Quantitative ? Qualitative ? Observational? Adopted a phenomenological-hermeneutic method (naı̈ve understanding ? thematic structural analysis ? comprehensive understanding) for interpretation of the transcribed narrative responses to a semi-structured interview format. Interview length ranges from 50 min to 2 h long Qualitative Method/measures Implication: Early intervention to brief parents on additional stressors, e.g. finances to be considered in overall preparation Complexity of the child’s disease and parents’ SES was linked to higher levels of stress experienced in the domains identified Thematic analysis revealed two major categories of parents’ perceptions of the cost burden associated with having a child with CHD:(1) Lifestyle Changes and (2) Uncertainty—across three domains: financial, emotional and family Implications: importance of promoting normalisation among mothers of children with CHD and ensuring a sufficient support system Qualitative data revealed mothers of CHD children reporting high levels of vigilance with their children Quantitative (MANOVA) and parent–child interaction results show similarity between mothers of children with CHD and controls in terms of parenting practices and in their experiences of parental stress related to childrearing issues. Reported child behaviour was similar across the two groups Implications: mothers receiving personcentred and family-centred care feel more supported and are more likely to adapt to the stresses of parenting a child with CHD Mothers who feel supported were more likely to adapt to the stresses of parenting a child with CHD Mothers receiving person-centred and family-centred care reported feeling more supported Perception that improved coordination of care and greater privacy would be supportive Need for practical support to overcome limitations in daily life Key themes identified in the qualitative analysis included: Key findings Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol Child’s characteristics Infants with mild (N = 92), moderate (N = 50) or severe CHD (N = 70) Children with CHD (various severity levels) aged 9 days–13.6 years (M = 1.7 years) Infants with significant CHD Sample size/country N = 212 mothers/Norway N = 52 mothers/USA N = 70 parents/UK Study Mothers of infants with CHD: well-being from pregnancy through the child’s first 6 months Psychological Adaptation and Adjustment of Mothers of Children With CHD: Stress, Coping, and Family Functioning Predictors of psychological functioning in mothers and fathers of infants born with severe CHD References Dale et al. [11] Davis et al. [12] Doherty et al. [13] Table 1 continued The 60-item situational version of COPE (The Carver, Scheier and Weintraub’s multidimensional coping inventory) The 53-item BSI (general severity index score); Quantitative Cognitive processes (maternal appraisal of stress, expectations, methods of coping, family functioning and maternal psychological adjustment (Derogatis’ BSI)) Illness variables (15 prevalent types of heart defects) Self- report inventories and a brief structured interview that measure: Quantitative ? Qualitative Maternal mental health was predicted by (1) maternal coping skills (:behavioural disengagement : psychological distress); (2) understanding of the diagnosis (;understanding : psychological distress); and (3) the degree of cohesive family functioning (;cohesiveness : psychological distress) Mann–Whitney between-group comparisons revealed elevated levels of clinically significant psychological distress in mothers, compared to fathers, and differences between parents in coping styles were found using MANCOVA Regression analyses showed after controlling for maternal education and defect severity, daily hassles and method of coping accounted for a significant amount of variance in maternal adjustment scores. In contrast, family supportiveness accounted for\1 % of the remaining variance. All five variables accounted for approximately 38 % of the variance in maternal adjustment scores Bivariate correlations reveal poorer maternal adjustment (BSI scores) was associated with high levels of daily stress and palliative coping techniques and was not significantly associated with severity of the cardiac defect Implication: The resilience of families is underscored by this study. Need to explore whether there is a risk of future longer-term stressors in relation to the child with CHD that will wear out individual resources after the initial period of mobilisation of forces to achieve adaptation Mothers of children with severe CHD reported significantly more anger at 6 months post-partum Parametric analyses revealed that mothers of children with CHD showed a similar level of satisfaction with life and feelings of joy as mothers of children without CHD both during pregnancy and when the child was 6 months old Quantitative Longitudinal case-cohort design mothers completed mailed questionnaires with assessment points at gestation week 30 (T1) and at child’s age of 6 months (T2). Subjective well-being was measured by The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS), The Joy and Anger scales (from Differential Emotions Scale) and a single item on social support Key findings Method/measures Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 123 Study Parent stress levels during children’s hospital recovery after congenital heart surgery Quality of Life in Families of Children with CHD References Franck et al. [14] Goldbeck and Melches [17] Table 1 continued 123 N = 69 patients and their caregivers/Germany N = 211 parents/UK Sample size/country Children aged 7–20 years of age with CHD Children 1 day–16 years of age admitted for elective open and closed heart surgery at a London hospital Child’s characteristics Parents’ perceptions of their children’s illness severity correlated with an objective measure of post-operative morbidity Measures: ULQIE for parental QL LQ-KID-E for patient’s proxyreported QL completed by parents 27-item LQ-KID for patients selfreported QL Quality of Life (QL)—assessment: Quantitative Implication: Psychosocial interventions should be family-focused and provide support for patients’ and their caregivers’ QL Significant interaction effect of parental QL and patients’ self-reported QL in predicting parental proxy reports on their children’s QL. Parents with low own QL agree significantly more with their children than parents with high QL Parental QL was correlated with both the children’s self-rated QL and children’s parent-rated QL Children’s self-rated and proxy-rated QL correlated moderately, with the highest intra-class correlation on the subscale psychological well-being/functioning Paired Pearson correlations and regression analyses revealed: Implications: Better identification of parents at risk of high stress and specific interventions to improve parental support and coping are needed pre- and postoperatively Parents in more deprived communities and mothers born outside the UK had higher stress scores Few differences between mothers’ and fathers’ stress or their perceptions of their children’s illness Parental stress remained moderate to high throughout their children’s hospitalisation regardless of the severity of illness 22-item self-report Parent Stressor Scale: Infant Hospitalisation (PSS-IH) Parametric or nonparametric tests revealed Parents completed questionnaires and structured interviews preoperatively and on postoperative days 3, 5, 8 and 15 Paternal mental health difficulties were linked to the psychological factors of worry and maladaptive coping strategies such as disengagement through alcohol use Key findings Quantitative Method/measures Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol CHD, parental stress and infant– mother relationships Predictors of Parental Quality of Life after Child Open-Heart Surgery: A 6-Month Prospective Study Goldberg et al. [19] Landolt et al. [37] Infants with CHD Children (aged 0 to 16 years) with CHD who had undergone openheart surgery N = 42 ? 46 as control (all mothers)/ Canada N = 232 (135 mothers and 97 fathers)/ Switzerland Questionnaire-based data were collected at two occasions: T1—discharge and T2—six months after surgery. Measures included: SF36 to measure parent’s HRQoL; German version of the 26-item Post-Traumatic Distress Scale to assess surgery-related posttraumatic stress symptoms; 15-item Revised Impact on Family Scale (IOS) to measure the impact of the child’s disease on the family Quantitative Chi-square tests to compare data on measures between CHD and healthy group. These include: Infant–mother attachment assessment using the strange situation to classify dyads according to three major patterns: secure dyad, insecure–avoidant dyad and insecure–resistant dyad; Parenting stress Index (120-item); Rutter Health Questionnaire (24-item symptom checklist); and child medical status Quantitative ? Observational Assessment Social risk factors—defined as single-parent status, ethnic minority status, unfinished parental education or professional training, and/or unemployment Ulm Inventory for Parents which measures physical and daily functioning, satisfaction with the situation in the family, emotional stability, self-development and well-being Symptoms of PTSD at discharge and a high IOS score at 6 months were associated with lower mental component scores on HRQoL in both parents All impaired domains of parental HRQoL at discharge significantly improved over time and were within or above population norms 6 months later Mothers had lower HRQoL than fathers Both mothers and father showed lower levels of HRQoL at discharge in domains such as role limitations due to physical and emotional problems A range of statistical analyses were performed including Chi-square analyses for nominal variables comparisons; one-sample Student’s t tests for testing between-group differences; and Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank tests to compare scores at T1 vs. T2 Securely attached infants showed more subsequent improvement in health than insecurely attached infants showed No significant differences between the secure and insecure infants with CHD on parental stress or well-being measure Chi-square tests indicated that infants with CHD were less likely to be securely attached to their mothers than the healthy group. More avoidant babies were identified in the CHD group Implication: Programmes providing psychosocial support for children with CHD and their caregivers should consider risk factors which are both medical and social A significant interaction effect indicated a cumulative negative impact of disease severity and social disadvantage on the quality of life of the patients Significant effects of social disadvantage on the quality of life of both the children and their parents Significant effects of disease severity on children’s’ quality of life Three measures were employed: *Severity of the disease was evaluated by the responsible paediatrician ANOVA results demonstrated: Quantitative Children with various severities* of CHD with ages ranged from 0 to 21 years N = 132 families of children with CHD/ Germany The impact of the severity of disease and social disadvantage on quality of life in families with CHD. Goldbeck and Melches [18] Ulm Inventory for Children which measures physical well-being, psychological wellbeing, disease- and therapy-related distress, family relations and general quality of life perception Key findings Method/measures Child’s characteristics Sample size/country Study References Table 1 continued Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 123 Study Distress and hopelessness among PCCHD and parents of children with other diseases, and parents of healthy children Psychosocial morbidity among PCCHD: A prospective longitudinal study References Lawoko and Soares [38] Lawoko and Soares [39] Table 1 continued 123 Quantitative Children born with CHD between 0 and 20 years of age who were living at home, with parents with responsible for their care or in close contact with them during the survey Children between 0 and 20 years of age with CHD N = 1092 PCCHD ? 112 parents of children with other diseases (PCOD) ? 293 randomised healthy control group (PHC)/ Sweden N = 632 parents/Sweden Longitudinal quantitative design, data collected twice, a year apart. Repeated measures covering (1) children’s demographic and clinical characteristics; (2) Caregiving time/burden (use of Symptom Check List- Revised (SCL-90-R) and Hopelessness Scale to assess psychosocial morbidity); (3) 12-item Schedule for Social interaction; (4)15-item Pyramid Patient Questionnaire and 8-item Client Satisfaction Questionnaire; (5) Parental financial situation Cross-sectional questionnaire administration in a 20-day period with measures on distress (SCL90-R) and hopelessness (20-item Hopelessness Scale) Method/measures Child’s characteristics Sample size/country Long-standing psychosocial morbidity (at both T1 and T2) was also relatively high (7–22 %) Univariate analyses including independentsample t test, paired-sample t test, and Chisquare test plus blockwise logistic regression analyses were performed. High point prevalence of depression, anxiety, somatisation, and hopelessness symptoms among PCCHD both at T1 (14–31 %) and T2 (15–38 %); Higher severity of symptoms reported by mothers than fathers Implications: Programme interventions should be targeted at parents, in particular PCCHD who are at risk of developing psychosocial problems Variables such as employment status and financial situation explained more of the variation in distress and hopelessness among parents than the diseases of their children There were no differences in distress and hopelessness between PCOD and PHC Fathers of children with CHD had higher distress than fathers belonging to the other groups Mothers within all parent groups had higher levels of distress and hopelessness than fathers, with the highest levels among mothers of children with CHD compared to mothers in the other groups PCCHD had higher scores on distress and hopelessness than PCOD and PHC. A significant number of parents, in particular PCCHD, reported levels of distress and hopelessness within/above psychiatric outpatients and depressed people, respectively Parametric and nonparametric tests (ANOVAs, Chi-square tests, t tests, Dunn’s/Bonferroni post hoc tests and blockwise logistic regression analyses) results revealed: Implications: Parents in whom the child’s CHD has a high impact on the family are at increased risk of persistent low mental HRQoL Key findings Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol N = 53 (25 parents ? 28 grandparents)/Canada Facets of Parenting a Child with HLHS. Patients with univentricular heart in early childhood: parenting stress and child behaviour Rempel et al. [45] Sarajuuri et al. [49] N = 37 parents of newborns with CHD ? 46 parents of healthy control (gender-matched newborns)/Finland Children age 6 months–4.5 years who had undergone surgery for CHD (N = 15) N = 53 (25 parents ? 28 grandparents)/Canada Parenting under Pressure: a grounded theory of parenting young children with lifethreatening CHD Rempel et al. [46] 23 newborns with HLHS and 14 newborns with univentricular heart defects (UVH) Children age 6 months–4.5 years who had undergone surgery for HLHS. (N = 15) Child’s characteristics Sample size/country Study References Table 1 continued Parenting Stress Index (PSI) Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL) Measures: Quantitative A review of descriptive and intervention studies in CHD Knowledge from clinical practice in nursing children with HLHS Conceptual memos written by the researchers as part of the analytic process, Transcriptions ? audio recordings, and field notes of the 53 previously conducted interviews, Four data sources were used to conceptualise the parenting needs for young children with CHD: Qualitative and Observational (Secondary analysis of data from Study 19) Telephone and in-person recorded interviews were conducted. Participants were asked to recount experiences from the time of the child’s diagnosis to the present Using a constructive grounded theory study design, data collection and data analysis occurred simultaneously (using NVivo 8) to capture a full range of parenting experiences from multiple family members and from each stage of the surgical trajectory. Qualitative Method/measures Parents of children with HLHS reported significantly more total and internalising behaviour problems than the controls. For the syndrome scales, a significant difference was only found in somatic complaints Statistical analyses using independent- and paired-sample t tests revealed significantly higher PSI mean score among the mothers and fathers of children with HLHS compared to controls Supported parenting (We did what we could do to help) Uncertain parenting (We didn’t know what to expect) Expert parenting (She became a nurse) ‘Hands-off’ parenting (There’s nothing we could do) Survival parenting (It will test you to the utmost) Interpretation of the data led to the conceptualisation of a model of five facets of parenting of children with CHD. Each facet constitutes a critical component for educational or psychosocial intervention for parents: Implications: Interventions that focus on helping carers to move through the four phases may help them safeguard the survival of their children, and their own survival as parents as they manage multiple demands (4) encountering new challenges (3) watching for and accommodating the unexpected; and (2) becoming increasingly attached; (1) realising and adjusting to the inconceivable; Qualitative analysis revealed four overlapping and re-emerging phases: Implication: Psychosocial intervention may be beneficial Higher psychosocial morbidity associated with parental caregiving burden, dissatisfaction with care, social isolation, and financial instability rather than children’s clinical severity Key findings Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 123 123 Children under age 12 with newly diagnosed CHD (within the last 3–4 months of the study) N = 92 two-parent families/USA Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s CHD Tak and McCubbin [57] The Coping Health Inventory for Parents (CHIP) Personal Resources Questionnaire (PRQ-85) Implications: Interventions developed for PCCHD need to focus on building resilience through social support Child and family characteristics (such as child’s age and family stress) were significant predictors of perceived social support and parental coping Perceived social support operated as a resiliency factor between family stress and both parental and family coping The Family Inventory of Life Events (FILE) Regression Analyses revealed: Both parents independently completed instruments on: Mothers also appeared to seek social support more often compared to fathers PCCHD showed weaker tendency to use styles of coping such as reassuring thoughts and less often expressed negative emotions (anger, annoyance) compared to the reference group as measured by UCL Statistical analyses performed using onesample t tests and univariate analyses of (co)variance. Results showed parents of children treated for CHD had lower levels of distress, manifested as lower levels of somatic symptoms, anxiety and sleeplessness and serious depression compared with reference group. Favourable long-term outcomes may be due to the good to excellent prognosis of the CHD conditions that this sample had. The authors did highlight that overall this sample did not require further reinterventions or reoperations and hence the results may not be considered representative for parents of patients with complex malformations. Mothers of children with CHD reported significantly more somatic symptoms than fathers Implications: The stress reported by parents indicates the need for early psychosocial support for the families of these seriously ill patients The parents of patients with UVH did not differ from the controls in terms of PSI score or reported CBCL scores Key findings Quantitative The Utrecht Coping List (UCL) (7-scales) The 28-item version of General Health Questionnaire (assess levels of psychological distress); Quantitative Children and adolescents aged from 7 to 15 years who underwent invasive treatment for CHD N = 109 (52 sets of both parents; 48 mothers and 9 fathers)/Netherlands Long-term psychological distress, and styles of coping, in parents of children and adolescents who underwent invasive treatment for CHD Spijkerboer et al. [55] Method/measures Child’s characteristics Sample size/country Study References Table 1 continued Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol Child’s characteristics Children who underwent openheart surgery over the period 2002 through 2007 with mean age at assessment of 45.3 months. Children aged from birth to 16.9 years Sample size/country N = 114 mothers ? 82 fathers/Netherlands N = 3 groups of parents of 75 children who—(1. undergone surgery for CHD (PCCHD); 2. transplantation of bone marrow (PCOD); 3. healthy (PHC))/UK Study A multi-centric study of diseaserelated stress, and perceived vulnerability, in parents of children with CHD Psychological functioning in parents of children undergoing elective cardiac surgery References VrijmoetWiersma et al. [60] Wray and Sensky [62] Table 1 continued Utrecht coping list Dyadic adjustment scale General health questionnaire Measures: Parents of the children undergoing cardiac surgery or transplantation of bone marrow were assessed before the procedure and again 12 months after these procedures, whilst the healthy group were assessed on two occasions, 12 months apart. Quantitative Child Vulnerability Scale. State-Trait Anxiety Index Parental Stress Index-Short Form General Health Questionnaire The Paediatric Inventory for Parents (short form) Few differences between any of the groups on the other parameters, and the evaluated indexes showed stability over time Following treatment, there was a significant reduction in the levels of distress in PCCHD and PCOD PCCHD and PCOD both had significantly higher rates of distress prior to the surgical procedures than did PHC Results using combination of parametric and nonparametric tests revealed: Implications: Psychosocial screening of parents of children with CHD is important in order to provide appropriate counselling to those parents most in need Severity of the lesion did not influence parental levels of stress, but parents of children with HLHS reported higher levels of stress than other parents Risk factors for increased anxiety and perceived vulnerability included number of surgical procedures, time since the last procedure, and ethnicity PCCHD reported significantly higher rates of perceived vulnerability than did parents of healthy children State anxiety levels were higher in mothers of children with CHD. Parents of children with CHD did not report higher generic nor disease-related stress scores, and parenting levels of stress were also comparable to reference groups Statistical analysis using independent t tests, ANOVA and forced entered regression analyses were performed to compare parental responses with the reference groups on the instruments used and to determine the predictors of perceived vulnerability and parenting stress. Analyses showed: Quantitative Cross-sectional study using both generic and disease-related measures for assessment: Key findings Method/measures Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 123 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol The timing of diagnosis and treatment also seemed to play a role in the findings reported. For example, Wray and Sensky [62] found that following CHD treatment, there was a significant reduction in the levels of distress in PCCHD. Moreover, prenatal versus post-natal diagnosis of CHD seems to impact on the psychological distress in PCCHD. Contrary to their hypothesis, Brosig et al. [6] found that the level of distress for parents in the prenatal group remained significantly higher than test norms from diagnosis to 6 months after birth. Considering the financial burden placed on families of children with CHD, Connor et al. [10] in their qualitative study noted that prenatal diagnosis could trigger financial uncertainty in family members and often resulted in altered personal spending prior to birth. In terms of mental health outcomes for PCCHD, Dale et al., [11] reported a somewhat different pattern of findings. Using measures of subjective well-being rather than clinical psychological assessment tools, the study found similar levels of life satisfaction and positive emotions such as feelings of joy in mothers of children with and without CHD, both during pregnancy and at 6 months postpartum. Family Functioning Complexity of the child’s disease and parents’ socioeconomic status were linked to higher levels of family uncertainty and more drastic changes in lifestyles where the impact on family functioning went beyond monetary issues. Families of children with more severe CHD (e.g. hypoplastic left heart syndrome—HLHS) reported more negative impact than families of children with milder forms of CHD, particularly in the domains of familial burden (including more problems with siblings), social relationships, mastery, financial burden and personal strain [1, 5, 10]. Nevertheless, parental caregiving burden, dissatisfaction with care, social isolation and financial instability may be more important for PCCHD’s psychosocial experiences than the sole presence and severity of CHD in children [39]. For example, according to some studies, socioeconomic stressors such as unemployment and financial strain explained more of the variation in psychosocial experiences among PCCHD than the diseases of their children [14, 18, 38]. Quality of Life Research on the quality of life (QoL) of PCCHD (i.e. individual’s subjective perception of physical, psychological and social functioning) produced contrasting findings where different approaches and measurement tools were used with different samples. For example, similar QoL scores were found between parents of different CHD diagnostic groups (HLHS vs. TGA) and healthy controls using the Paediatric 123 Quality of Life Inventory [5]. Another study, however, using Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) revealed that PCCHD (particularly for parents with younger age, rheumatic heart disease and female children) reported significantly poorer health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The most significant differences were found in the domains of general health, vitality and physical role limitation [2]. Some QoL studies have utilised multi-informant strategies including proxy and self-reports to integrate different viewpoints which allows a more comprehensive assessment of QoL of the whole family over time. Landolt et al. [37] found that mothers showed lower HRQoL than fathers at discharge. At 6 months after surgery, a higher impact of the child’s disease on family life was a risk factor for a low mental HRQoL in both mothers and fathers. Parents’ selfreported QoL is also shown to be associated with children’s self-reported HRQoL [17]. Coping Psychological Functioning In the literature reviewed, several studies used the transactional stress and coping model to better understand the psychological functioning of families and coping at different stages of the diagnosis/treatment and in both mothers and fathers. A lower degree of maternal health and adjustment was found to be associated with maladaptive coping strategies (e.g. avoidance/behavioural disengagement, denial/wishful thinking) but was unrelated to the severity of heart defects [12, 13]. Perceived social support was found to be an important factor that positively related to individual parental coping [57]. Gender and Age Differences Gender and age differences were found between styles of coping in PCCHD. Mothers appeared to ‘vent’ more about the situation, seek more social support (both instrumental and emotional) and avail themselves of more spiritual and religious support compared to fathers, who used alcohol significantly more than mothers [13, 55]. Younger mothers reported more helpful coping related to family integration, cooperation and optimism, whereas for younger fathers helpful coping was related to maintaining social support, self-esteem and psychological stability [57]. Parenting Parenting Stress One study employing the Parent Stressor Scale: Infant Hospitalisation found that the stress levels of PCCHD Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol remained moderate to high throughout their children’s hospitalisation regardless of the severity of illness [14]. The general consensus of the parental stress studies was that parent stress levels related to child rearing more generally, as distinct from the specific period of hospitalisation, did not differ between PCCHD and healthy controls. However, within the CHD group, parents of children with HLHS reported more parenting stress than parents of children with minor forms of heart defect (e.g. TGA) [33, 36, 50, 53]. Parenting children with HLHS who are at risk of mortality and morbidity explained the high levels of pressure and stress that this group of parents experienced as they have to constantly watch for and accommodate the uncertainties and challenges that arise in their parenting journey [45]. Parenting Practices/Style Contrasting findings in parenting styles using the Parent Behaviour Checklist (PBC) were reported in the studies reviewed. Some reported more permissive styles of parenting in PCCHD than in the parents of healthy controls [5], whereas others showed similarity in nurturing and discipline practices by mothers in both the CHD and healthy control groups. The contrasting findings are consistent with Rempel et al. [45] 5-facet parenting practices model which articulates the diverse and multi-faceted experiences and needs of PCCHD. The Role of Attachment Style The studies also identified the protective role of attachment security for both the parent raising a child with CHD and the child themselves. More instances of avoidant attachment style were identified in the CHD group as compared to the healthy control group. Those infants who were securely attached to their mothers showed more subsequent improvement in health than insecurely attached infants [19]. Avoidant mothers of CHD children, particularly those with severe levels of CHD, were found to experience the greatest deterioration in mental health and marital satisfaction over time with impacts on their children’s emotional issues and self-image [3]. These studies highlight the importance of supporting mothers living with young children with CHD by providing person-centred and familycentred care, reinforcing the findings of Bruce et al. [7]. Conclusion and Implications for Clinical Practice This review of the familial impact of CHD and parenting practices of PCCHD did not yield conclusive results. However, there was a consensus that PCCHD who have fewer psychosocial resources and less support may be at risk of higher psychological distress and lower well-being, for both the parent and the child and that this impact may persist over time. This review generally supports the assertion by Jackson et al. [26] that the psychosocial impacts on families of children with complex conditions may be determined by individual and family factors beyond the severity of the child’s condition. Parenting coping programmes for children with HLHS were indicated, however. The findings on familial coping were consistent with previous findings on the importance of helping families to identify existing coping patterns and parenting practices particularly at the diagnostic stage [24, 28]. Familial factors such as cohesiveness and adaptive parental coping strategies appear to be paramount for successful parental adaptation to CHD in their child, which in turn plays a significant role in parents’ and children’s long-term well-being. The resilience of families of children with CHD is underscored, although normalising parental anxiety and developing interventions to manage this anxiety is highlighted, along with the need to monitor familial impacts and coping over time to identify those parents who may need continuing or renewed support. Assessment of familial impact may be achieved through the use of a psychosocial assessment measure, in recognition of the multiplicity of factors determining impact and coping. A useful example of such a measure is the Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.0), developed for use with families of paediatric cancer patients [43]. This tool, which appears to be modifiable for CHD families, assesses psychosocial risk within a number of domains: family structure and resources, family social support, family problems, parent stress reactions, family beliefs, child problems and sibling problems. Such a measure could be administered at prenatal or post-natal diagnosis, at first or subsequent major surgeries, and post-psychosocial intervention. The review implies a holistic approach in the paediatric care of CHD children and their families through understanding and addressing the diverse and multi-faceted experiences and needs of PCCHD. Early psychosocial intervention programmes for PCCHD should go beyond the examination of parental stress and family functioning to include specific interventions targeting improved adaptive coping and enhanced productive parenting practices. These interventions should also be aimed at reducing structural or systemic contributors to impaired coping and poorer attachment outcomes. Interventions to promote coping should target promotion of maternal attachment in the immediate post-diagnosis period, particularly where children have severe CHD. Monitoring of familial impact and parental coping over time, through the use of a CHD version of the PAT 2.0, or similar tool is warranted. Added to this is monitoring of 123 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol how parents cope in the hospital environment, a factor known to be important in familial adjustment to serious childhood medical conditions [27]. The four-phase model [46] which suggests that parents need to realise and adjust to the inconceivable; become increasingly attached; watch for and accommodate the unexpected; and encounter and deal with new challenges provides a useful guide for health professionals working with PCCHD in gauging the capacity of parents to adjust and cope. The use of a validated psychosocial risk screen for all PCCHD would enable the early identification of those parents and families who are at risk, and their allocation to the most relevant psychosocial intervention protocol, based on a framework such as the pediatric psychosocial preventative health model (PPPHM) [29, 33]. This model builds on the assumption that most families can cope with their child’s condition, but that some will need assistance to deal with their distress and to possibly learn new coping and parenting skills. Using public health concepts, the PPPHM, based on a validated risk assessment, will allocate families who are transiently distressed but basically resilient, to universal services, such as psycho-education; families with acute distress and other risk factors, such as avoidant forms of coping, to targeted services; and families with multiple original or escalating risk factors, to clinical services [9]. This screening and differential diagnosis of level of psychosocial risk can streamline allocation of services and enhance the specificity of service provision in health services with limited resources. As with acute care, the severity of psychosocial risk demands a proportional response in terms of number and composition of a multidisciplinary team to provide the appropriate intervention [53]. In paediatric cancer settings, universal care typically involves the medical team with access to allied health, for example, on request [41]. In a PPPHM-oriented service, targeted and clinical interventions may involve a paediatric nephrologist, nurse clinician, dietician, social worker and psychologist [41]. A paediatric cardiac multidisciplinary team, in addition to the cardiologist, may include the same range of allied health professionals, with adjustments according to the level of risk. In some cases, universal interventions may require a health psychologist, targeted interventions may require a neuropsychologist, whilst some clinical interventions may require a clinical psychologist or family therapist, especially if dealing with pre-existing comorbidities in parents and family members or dealing with acute distress with dysfunctional familial coping patterns or dysfunctional parenting style. The approach suggested here of universal screening and selective multidisciplinary intervention requires a strong organisational commitment, rather than just an individual clinician or departmental commitment. It can be justified, 123 however, in terms of its contribution to secondary prevention and increased family and child well-being. Acknowledgments This review was undertaken as part of a larger study, the Heart Child Family Project, conducted by the Heart Research Centre (HRC) and the Melbourne Graduate School of Education, University of Melbourne, funded by HeartKids Australia under the 2014 Grants-in-Aid program. References 1. Almesned S, Al-Akhfash A, Mesned AA (2013) Social impact on families of children with complex congenital heart disease. Ann Saudi Med 33(2):140 2. Arafa MA, Zaher SR, El-Dowaty AA, Moneeb DE (2008) Quality of life among parents of children with heart disease. Health Qual Life Outcomes 6:91. doi:10.1186/1477-7525-6-91 3. Berant E, Mikulincer M, Shaver PR (2008) Mothers’ attachment style, their mental health, and their children’s emotional vulnerabilities: a 7-year study of children with congenital heart disease. J Personal 76(1):31–65. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00479.x 4. Bright MA, Franich-Ray C, Anderson V, Northam E, Cochrane A, Menahem S, Jordan B (2013) Infant cardiac surgery and the father–infant relationship: feelings of strength, strain, and caution. Early Hum Dev 89(8):593–599. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev. 2013.03.001 5. Brosig CL, Mussatto KA, Kuhn EM, Tweddell JS (2007) Psychosocial outcomes for preschool children and families after surgery for complex congenital heart disease. Pediatr Cardiol 28(4):255–262 6. Brosig CL, Whitstone BN, Frommelt MA, Frisbee SJ, Leuthner SR (2007) Psychological distress in parents of children with severe congenital heart disease: the impact of prenatal versus postnatal diagnosis. J Perinatol 27(11):687–692. doi:10.1038/sj. jp.7211807 7. Bruce E, Lilja C, Sundin K (2014) Mothers’ lived experiences of support when living with young children with congenital heart defects. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 19(1):54–67. doi:10.1111/jspn.12049 8. Carey LK, Nicholson BC, Fox RA (2002) Maternal factors related to parenting young children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Nurs 17(3):174–183. doi:10.1053/jpdn.2002.124111 9. Committee on Health and Behavior: Research, Practice, and Policy, Board on Neuroscience and Behavioral Health (2001) Health and behavior: The interplay of biological, behavioral and societal influences Washington: National Academies Press 10. Connor JA, Kline NE, Mott S, Harris SK, Jenkins KJ (2010) The meaning of cost for families of children with congenital heart disease. J Pediatr Health Care 24(5):318–325. doi:10.1016/j. pedhc.2009.09.002 11. Dale M, Solberg Ø, Holmstrøm H, Landolt M, Eskedal L, Vollrath M (2012) Mothers of infants with congenital heart defects: well-being from pregnancy through the child’s first six months. Qual Life Res 21(1):115–122. doi:10.1007/s11136-0119920-9 12. Davis CC, Brown RT, Bakeman R, Campbell R (1998) Psychological adaptation and adjustment of mothers of children with congenital heart disease: stress, coping, and family functioning. J Pediatr Psychol 23(4):219–228 13. Doherty N, McCusker CG, Molloy B, Mulholland C, Rooney N, Craig B, Sands A, Stewart M, Casey F (2009) Predictors of psychological functioning in mothers and fathers of infants born with severe congenital heart disease. J Reprod Infant Psychol 27(4):390–400. doi:10.1080/02646830903190920 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 14. Franck LS, McQuillan A, Wray J, Grocott MPW, Goldman A (2010) Parent stress levels during children’s hospital recovery after congenital heart surgery. Pediatr Cardiol 31(7):961–968. doi:10.1007/s00246-010-9726-5 15. Franich-Ray C, Bright MA, Anderson V, Northam E, Cochrane A, Menahem S, Jordan B (2013) Trauma reactions in mothers and fathers after their infant’s cardiac surgery. J Pediatr Psychol 38(5):494–505. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jst015 16. Frydenberg E, Deans E (2012) The early years coping project: building a shared language of coping. In: Molinelli B, Grimaldo V (eds) Handbook of psychology of Coping: New Research. Nova Publishers, New York, pp 225–242 17. Goldbeck L, Melches J (2005) Quality of life in families of children with congenital heart disease. Qual Life Res 14(8):1915–1924. doi:10.1007/s11136-005-4327-0 18. Goldbeck L, Melches J (2006) The impact of the severity of disease and social disadvantage on quality of life in families with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young 16(1):67–75 19. Goldberg S, Simmons RJ, Newman J, Campbell K, Fowler RS (1991) Congenital heart disease, parental stress, and infantmother relationships. J Pediatr 119(4):661–666. doi:10.1016/ S0022-3476(05)82425-4 20. Graetz BW, Shute RH, Sawyer MG (2000) An Australian study of adolescents with cystic fibrosis: perceived supportive and nonsupportive behaviours from family and friends and psychological adjustment. J Adolesc Health 26:64–67 21. Graf A, Landolt MA, Mori AC, Boltshauser E (2006) Quality of life and psychological adjustment in children and adolescents with neurofibromatosis type 1. J Pediatr 149:348–353 22. Green A, Meaux J, Huett A, Ainley K (2009) Constantly responsible, constantly worried, constantly blessed: parenting after pediatric heart transplant. Prog Transpl 19(2):122–127 23. Grootenhuis MA, Last BF (1995) Adjustment and coping by parents of children with cancer: a review of the literature. Support Care Cancer 5:466–484 24. Hiscock H, Williams L, Incledon E, Flowers A (2012) Supporting mental health, resilience and wellbeing in families experiencing a childhood chronic illness: A synthesis of evidence to support the Childhood Illness Resilience Program. Prepared for the Hunter Institute of Mental Health. Melbourne: Centre for Community Child Health & Murdoch Children’s Research Institute 25. Hoddap R, Dykens E, Masino L (1997) Families of children with Prader-Willi syndrome—stress-support and relations to child characteristics. J Autism Dev Disord 27(1):11–24 26. Jackson AC, Tsantefski M, Goodman H, Johnson B, Rosenfeld J (2003) The Psychosocial impacts on families of low-incidence, complex conditions in children: the case of craniopharyngioma. Soc Work Health Care 38(1):81–107 27. Jackson AC, Stewart H, O’Toole M, Tokatlian N, Enderby K, Miller J, Ashley D (2007) Pediatric brain tumour patients: their parents’ perceptions of the hospital experience. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 24(2):95–105 28. Jackson AC, Enderby K, O’Toole M, Thomas SA, Ashley D, Rosenfeld JV, Simos E, Tokatlian N, Gedye R (2009) The role of social support in families coping with childhood brain tumour. J Psychosoc Oncol 27(1):1–24 29. Kazak AE (2006) Pediatric psychosocial preventative health model (PPPHM): research, practice and collaboration in pediatric family systems medicine. Fam Syst Health 24:381–395 30. Kazak AE, Nachman GS (1991) Family research on childhood chronic illness: pediatric oncology as an example. J Fam Psychol 4(4):462–483 31. Kazak AE, Barakat LP, Meeske K, Christakis D, Meadows AT, Casey R et al (1997) Posttraumatic stress, family functioning and social support in survivors of childhood leukaemia and their mothers and fathers. J Consult Clin Psychol 65:120–129 32. Kazak AE, Cant MC, Jensen M, McSherry M, Rourke M, Hwang W-T et al (2003) Identifying psychosocial risk indicative of subsequent resource utilization in families of newly diagnosed pediatric oncology patients. J Clin Oncol 21:3220–3225 33. Kazak AE, Rourke MT, Alderfer MA, Pai ALH, Reilly AF, Meadows AT (2007) Evidence-based assessment, intervention and psychosocial care in pediatric oncology: a blueprint for comprehensive services across treatment. J Pediatr Psychol 32(9):1099–1110 34. Kupst M (1992) Long-term family coping with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. In: La Greca AM, Siegel LJ, Wallander JL, Walker CE (eds) Stress and coping in child health. The Guilford Press, New York 35. Kupst M, Shulman JL (1988) Long-term coping with pediatric leukemia: a six-year follow-up study. J Pediatr Psychol 13(1):7–22 36. Kupst M, Natta MB, Richardson CC, Sculman JL, Lavigne JV, Das L (1995) Family coping with pediatric leukemia: ten years after treatment. J Pediatr Psychol 20(5):601–617 37. Landolt MA, Buechel EV, Latal B (2011) Predictors of parental quality of life after child open heart surgery: a 6-month prospective study. J Pediatr 158(1):37–43. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2010. 06.037 38. Lawoko S, Soares JJF (2002) Distress and hopelessness among parents of children with congenital heart disease, parents of children with other diseases, and parents of healthy children. J Psychosom Res 52(4):193–208. doi:10.1016/S00223999(02)00301-X 39. Lawoko S, Soares JJF (2006) Psychosocial morbidity among parents of children with congenital heart disease: a prospective longitudinal study. Heart Lung: J Acute Crit Care 35(5):301–314. doi:10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.01.004 40. Martin C, Nisa M (1996) Meeting the needs of children and families in chronic illness and disease: a greater role for the G.P.? Aust Fam Physician 25(8):1273–1281 41. Menon S, Valentini RP, Kapur G, Layfield S, Mattoo TK (2009) Effectiveness of a multidisciplinary clinic in managing children with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4(7):1170–1175 42. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269. doi:10. 7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135 43. Pai ALH, Patino-Fernandez AM, McSherry M, Beele D, Alderfer MA, Reilly AT, Hwang W-T, Kazak AE (2008) The Psychosocial Assessment Tool (PAT2.) psychometric properties of a screener for psychosocial distress in families of children newly diagnosed with cancer. J Pediatr Psychol 33(1):50–62 44. PRISMA. (2012). PRISMA endorsers. Retrieved from: http:// www.prisma-statement.org/statement.htm 45. Rempel GR, Rogers LG, Ravindran V, Magill-Evans J (2012) Facets of parenting a child with hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Nurs Res Pract. doi:10.1155/2012/714178 46. Rempel GR, Ravindran V, Rogers LG, Magill-Evans J (2013) Parenting under pressure: a grounded theory of parenting young children with life-threatening congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs 69(3):619–630. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06044.x 47. Rodenburg R, Marle Meijer A, Dekovic M, Aldenkamp AP (2006) Family predictors of psychopathology in children with epilepsy. Epilepsia 47:601–614 48. Sanger MS, Copeland DR, Davidson ER (1991) Psychosocial adjustment among paediatric cancer patients: a multidimensional assessment. J Paediatr Psychol 16:463–474 49. Sarajuuri A, Lönnqvist T, Schmitt F, Almqvist F, Jokinen E (2012) Patients with univentricular heart in early childhood: parenting stress and child behaviour. Acta Paediatr 101(3):252–257. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2011.02509.x 123 Author's personal copy Pediatr Cardiol 50. Sawyer M, Spurrier N (1996) Families, parents and chronic childhood illness. Family Matters 44:12–15 51. Sawyer M, Antoniou G, Toogood I, Rice M (1997) Childhood cancer: a two-year prospective study of the psychological adjustment of children and parents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 36(12):1736–1743 52. Scholler G, Kasparian N, Winlaw D (2011) How to treat: congenital heart disease. Australian Doctor, 21st October. http:// www.australiandoctor.com.au/cmspages/getfile.aspx?guid=e534f 9bb-15fe-4691-8f3e-71d9007f4e1c 53. Scott I, Vaughan L, Bell D (2009) Effectiveness of acute medical units in hospital: a systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care 21(6):397–407 54. Sloper P (1996) Needs and responses of parents following the diagnosis of childhood cancer. Child: Care Health Dev 22(3):187–202 55. Spijkerboer AW, Helbing WA, Bogers AJJC, Van Domburg RT, Verhulst FC, Utens EMWJ (2007) Long-term psychological distress, and styles of coping, in parents of children and adolescents who underwent invasive treatment for congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young 17(6):638–645 56. Swallow VM, Jacoby A (2001) Mother’s coping with childhood chronic illness: the effect of presymptomatic diagnosis of vesicoureric reflux. J Adv Nurs 33(1):69–78 123 View publication stats 57. Tak YR, McCubbin M (2002) Family stress, perceived social support and coping following the diagnosis of a child’s congenital heart disease. J Adv Nurs 39(2):190–198. doi:10.1046/j.13652648.2002.02259.x 58. Theofanidis D (2007) Chronic illness in childhood: psychosocial adaptation and nursing support for the child and family. Health Sci J 1(2). http://www.hsj.gr/index.files/VOLUME1_2.htm 59. Thompson RJ Jr, Armstrong FD, Link CL, Pegelow CH, Moser F, Wang WC (2003) A prospective study of the relationship over time of behavior problems, intellectual functioning, and family functioning in children with sickle cell disease: a report from the cooperative study of sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Psychol 28:59–65 60. Vrijmoet-Wiersma CMJ, Ottenkamp J, van Roozendaal M, Grootenhuis MA, Koopman HM (2009) A multicentric study of disease-related stress, and perceived vulnerability, in parents of children with congenital cardiac disease. Cardiol Young 19(6):608–614. doi:10.1017/S1047951109991831 61. Woods NF, Haberman MR, Packard NJ (1993) Demands of illness and individual, dyadic, and family adaptation in chronic illness. West J Nurs Res 15(1):10–30 62. Wray J, Sensky T (2004) Psychological functioning in parents of children undergoing elective cardiac surgery. Cardiol Young 14(2):131–139