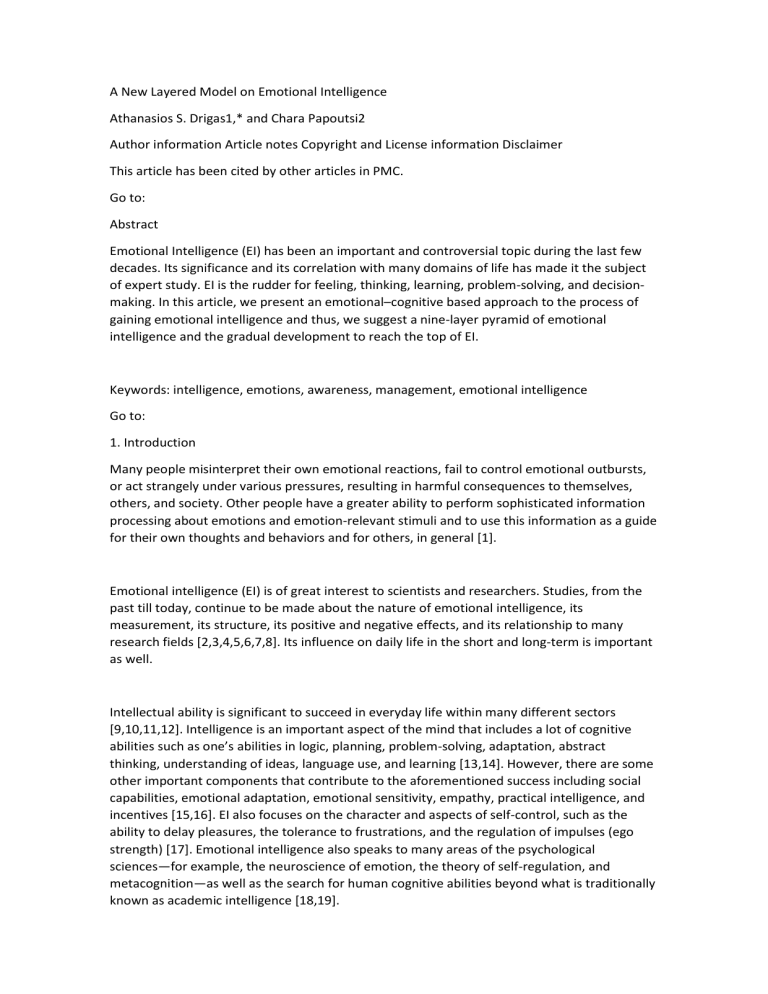

A New Layered Model on Emotional Intelligence Athanasios S. Drigas1,* and Chara Papoutsi2 Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer This article has been cited by other articles in PMC. Go to: Abstract Emotional Intelligence (EI) has been an important and controversial topic during the last few decades. Its significance and its correlation with many domains of life has made it the subject of expert study. EI is the rudder for feeling, thinking, learning, problem-solving, and decisionmaking. In this article, we present an emotional–cognitive based approach to the process of gaining emotional intelligence and thus, we suggest a nine-layer pyramid of emotional intelligence and the gradual development to reach the top of EI. Keywords: intelligence, emotions, awareness, management, emotional intelligence Go to: 1. Introduction Many people misinterpret their own emotional reactions, fail to control emotional outbursts, or act strangely under various pressures, resulting in harmful consequences to themselves, others, and society. Other people have a greater ability to perform sophisticated information processing about emotions and emotion-relevant stimuli and to use this information as a guide for their own thoughts and behaviors and for others, in general [1]. Emotional intelligence (EI) is of great interest to scientists and researchers. Studies, from the past till today, continue to be made about the nature of emotional intelligence, its measurement, its structure, its positive and negative effects, and its relationship to many research fields [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Its influence on daily life in the short and long-term is important as well. Intellectual ability is significant to succeed in everyday life within many different sectors [9,10,11,12]. Intelligence is an important aspect of the mind that includes a lot of cognitive abilities such as one’s abilities in logic, planning, problem-solving, adaptation, abstract thinking, understanding of ideas, language use, and learning [13,14]. However, there are some other important components that contribute to the aforementioned success including social capabilities, emotional adaptation, emotional sensitivity, empathy, practical intelligence, and incentives [15,16]. EI also focuses on the character and aspects of self-control, such as the ability to delay pleasures, the tolerance to frustrations, and the regulation of impulses (ego strength) [17]. Emotional intelligence also speaks to many areas of the psychological sciences—for example, the neuroscience of emotion, the theory of self-regulation, and metacognition—as well as the search for human cognitive abilities beyond what is traditionally known as academic intelligence [18,19]. In this paper, we are going to present the most discussed theories of intelligence, of emotions, and of emotional intelligence. We then present the construction of a 9-layer model (pyramid) of emotional intelligence which aims to show the levels a human must pass in order to reach the upper level of EI—emotional unity. The stratification of the pyramid of emotional intelligence is in tune with the pyramid of the functions of general intelligence [20]. Go to: 2. Research Findings 2.1. Theories of Intelligence The structure, nature, and characteristics of human intelligence have been discussed and have been the subject of debate since the time of Plato and Aristotle, at least a thousand years ago. Plato defined intelligence as a “learning tune” [21,22]. Under this concept, Plato and Aristotle put forth the three components of mind and soul: intellect, sentiment, and will [23]. The word “intelligence” comes from two Latin words: intellegentia and ingenium. The first word, considered in the way Cicero used the term, means “understanding” and “knowledge”. The second word means “natural predisposition” or “ability” [24]. At various points in recent history, researchers have proposed different definitions to explain the nature of intelligence [22]. The following are some of the most important theories of intelligence that have emerged over the last 100 years. Charles Spearman [25] developed the theory of the two factors of intelligence using data factor analysis (a statistical method) to show that the positive correlations between mental examinations resulted from a common underlying agent. Spearman suggested that the twofactor theory had two components. The first was general intelligence, g, which affected one’s performance in all mental tasks and supported all intellectual tasks and intellectual abilities [25,26]. Spearman believed that the results in all trials correlated positively, underlying the importance of general intelligence [25,27]. The second agent Spearman found was the specific factor, s. The specific factor was associated with any unique capabilities that a particular test required, so it differed from test to test [25,26]. Regarding g, Spearman saw that individuals had more or less general intelligence, while s varied from person to person in a job [28]. Spearman and his followers gave much more importance to general intelligence than to the specific agent [25,29]. In 1938, American psychologist Louis L. Thurstone suggested that intelligence was not a general factor, but a small set of independent factors that were of equal importance. Thurstone formulated a model of intelligence that centered on “Primary Mental Abilities” (PMAs), which were independent groups of intelligence that different individuals possessed in varying degrees. To detect these abilities, Thurstone and his wife, Thelma, thought up of a total of 56 exams. They passed the test bundle to 240 students and analyzed the scores obtained from the tests with new methods of Thurstone’s method of analysis. Thurstone recognized seven primary cognitive abilities: (1) verbal understanding, the ability to understand the notions of words; (2) verbal flexibility, the speed with which verbal material is handled, such as in the production of rhymes; (3) number, the arithmetic capacity; (4) memory, the ability to remember words, letters, numbers, and images; (5) perceptual speed, the ability to quickly discern and distinguish visual details, and the ability to perceive the similarities and the differences between displayed objects; (6) inductive reasoning, the extraction of general ideas and rules from specific information; and (7) spatial visualization, the ability to visualize with the mind and handle objects in three dimensions [30,31]. Joy Paul Guilford extended Thurstone’s work and devoted his life to create the model for the structure of intelligence. SI (Structure of Intellect theory, 1955) contains three dimensions: thought functions, thought content, and thought products. Guilford described 120 different kinds of intelligence and 150 possible combinations. He also discovered the important distinction between convergent and divergent thought. The convergent ability results in how well one follows the instructions, adheres to rules, and tries. The divergent ability decreases depending on whether or not one follows the instructions or if one has a lot of questions, and it usually means that one is doing the standard tests badly [32,33]. The Cattell-Horn Gf-Gc and the Carroll Three-Stratum models are consensual psychometric models that help us understand the construction of human intelligence. They apply new methods of analysis and according to these analyses, there are two basic types of general intelligence: fluid intelligence (gf) and crystallized intelligence (gc). Fluid intelligence represents the biological basis of intelligence. How fast someone thinks and how well they remember are elements of fluid intelligence. These figures increase in adulthood but as we grow older they decrease. Fluid intelligence enables a person to think and act quickly, to solve new problems, and to encode short-term memories. Crystallized intelligence, on the other hand, is the knowledge and skills acquired through the learning process and through experience. Crystallized abilities come from learning and reading and are reflected in knowledge trials, general information, language use (vocabulary), and a wide variety of skills. As long as learning opportunities are available, crystallized intelligence may increase indefinitely during a person’s life [14,34]. In the 1980s, the American psychologist Robert Sternberg proposed an intelligence theory with which he tried to extend the traditional notion of intelligence. Sternberg observed that the mental tests that people are subjected to for various intelligence measurements are often inaccurate and sometimes inadequate to predict the actual performance or success. There are people who do well on the tests but not so well in real situations. Likewise, the opposite occurred as well. According to Sternberg’s triarchic (three-part) theory of intelligence, intelligence consists of three main parts: analytical intelligence, creative intelligence, and practical intelligence. Analytical intelligence refers to problem-solving skills, creative intelligence includes the ability to handle new situations using past experiences and current skills, and practical intelligence refers to the ability to adapt to new situations and environments [35,36]. In 1983, psychologist Howard Gardner introduced his theory of Multiple Intelligences (MI), which, at that time, was a fundamental issue in education and a controversial topic among psychologists. According to Gardner, the notion of intelligence as defined through the various mental tests was limited and did not depict the real dimensions of intelligence nor all the areas in which a person can excel and succeed. Gardner argued that there is not only one kind of general intelligence, but rather that there are multiple intelligences and each one is part of an independent system in the brain. The theory outlines eight types of “smart”: Linguistic intelligence (“word smart”), Logical–mathematical intelligence (“number/reasoning smart”), Spatial intelligence (“picture smart”), Bodily–Kinesthetic intelligence (“body smart”), Musical intelligence (“music smart”), Interpersonal intelligence (“people smart”), Intrapersonal intelligence (“self smart”), and Naturalist intelligence (“nature smart”) [37,38]. 2.2. Emotions According to Darwin, all people, irrespective of their race or culture, express emotions using their face and body with a similar way as part of our evolutionary heritage [39,40]. Emotion is often defined as a complex feeling which results in physical and psychological changes affecting thought and behavior. Emotions include feeling, thought, nervous system activation, physiological changes, and behavioral changes such as facial expressions. Emotions seem to dominate many aspects of our lives as we have to recognize and to respond to important events related to survival and/or the maintenance of prosperity and, therefore, emotions serve various functions [41]. Emotions are also recognized as one of the three or four fundamental categories of mental operations. These categories include motivation, emotion, cognition, and consciousness [42]. Most major theories of emotion agree that cognitive processes are a very important source of emotions and that feelings comprise a powerful motivational system that significantly influences perception, cognition, confrontation, and creativity [43]. Researchers have been studying how and why people feel emotion for a long time so various theories have been proposed. These include evolutionary theories [44,45], the James-Lange Theory [46,47], the Cannon-Bard Theory [48], Schacter and Singer’s two-factor theory [49,50], and cognitive appraisal [51]. 2.3. Emotional Intelligence Anyone can become angry-that is easy. But to be angry with the right person, to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way-this is not easy. —Aristotle, The Nicomachean Ethics Thorough research has indicated the important role that emotions play in our lives in many fields [52,53,54,55]. Researchers have found that Emotional Intelligence is equal to or sometimes much more important than I.Q [56,57,58,59,60]. Emotion and intelligence are heavily linked [61,62,63]. If you are aware of your own and others’ feelings, this will help you manage behaviors and relationships and predict success in many sectors [64,65,66]. Emotional Intelligence is the ability to identify, understand, and use emotions positively to manage anxiety, communicate well, empathize, overcome issues, solve problems, and manage conflicts. According to the Ability EI model, it is the perception, evaluation, and management of emotions in yourself and others [67]. Emotional Intelligence (EI), or the ability to perceive, use, understand, and regulate emotions, is a relatively new concept that attempts to connect both emotion and cognition [68]. Emotional Intelligence first appeared in the concept of Thorndike’s “social intelligence” in 1920 and later from the psychologist Howard Gardner who, in 1983, recommended the theory of multiple intelligence, arguing that intelligence includes eight forms. American psychologists Peter Salovey and John Mayer, who together introduced the concept in 1990 [69], define emotional intelligence “as the ability to monitor one’s own and other’s emotions, to discriminate among them, and to use the information to guide one’s thinking and actions”. People who have developed their emotional intelligence have the ability to use their emotions to direct thoughts and behavior and to understand their own feelings and others’ feelings accurately. Daniel Goleman, an American writer, psychologist, and science journalist, disclosed the EI concept in his book named “Emotional Intelligence” [58,59,60]. He extended the concept to include general social competence. Goleman suggested that EI is indispensable for the success of one’s life. Mayer and Salovey suggested that EI is a cognitive ability, which is separate but also associated with general intelligence. Specifically, Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, and Sitarenios [70] suggested that emotional intelligence consists of four skill dimensions: (1) perceiving emotion (i.e., the ability to detect emotions in faces, pictures, music, etc.); (2) facilitating thought with emotion (i.e., the ability to harness emotional information in one’s thinking); (3) understanding emotions (i.e., the ability to understand emotional information); and (4) managing emotions (i.e., the ability to manage emotions for personal and interpersonal development). These skills are arranged hierarchically so that the perceptual emotion has a key role facilitating thinking, understanding emotions, and managing emotions. These branches are arising from higher order basic skills, which are evolved as a person matures [67,71]. According to Bar-On emotional-social intelligence is composed of emotional and social abilities, skills and facilitators. All these elements are interrelated and work together. They play a key role in how effectively we understand ourselves and others, how easily we express ourselves, but also in how we deal with daily demands [72]. Daniel Goleman (1998) defines Emotional Intelligence/Quotient as the ability to recognize our own feelings and those of others, to motivate ourselves, and to handle our emotions well to have the best for ourselves and for our relationships. Emotional Intelligence describes capacities different from, but supplementary to, academic intelligence. The same author introduced the concept of emotional intelligence and pointed out that it is composed of twenty-five elements which were subsequently compiled into five clusters: Self Awareness, Self-Regulation, Motivation, Empathy, and Social Skills [61,73]. Petrides and Furnham (2001) developed the Trait Emotional Intelligence model which is a combination of emotionally-related self-perceived abilities and moods that are found at the lowest levels of personality hierarchy and are evaluated through questionnaires and rating scales [74]. The trait EI essentially concerns our perceptions of our inner emotional world. An alternative tag for the same construct is trait emotional self-efficacy. People with high EI rankings believe that they are “in touch” with their feelings and can regulate them in a way that promotes prosperity. These people may enjoy higher levels of happiness. The trait EI feature sampling domain aims to provide complete coverage of emotional aspects of personality. Trait EI rejects the idea that emotions can be artificially objectified in order to be graded accurately along the IQ lines [75]. The adult sampling domain of trait EI contains 15 facets: Adaptability, Assertiveness, Emotion perception (self and others), Emotion expression, Emotion management (others’), Emotion regulation, Impulsiveness (low), Relationships, Selfesteem, Self-motivation, Social awareness, Stress management, Trait empathy, Trait happiness, and Trait optimism [76]. Research on emotional intelligence has been divided into two distinct areas of perspectives in terms of conceptualizing emotional competencies and their measurements. There is the ability EI model [77] and the trait EI [74]. Research evidence has consistently supported this distinction by revealing low correlations between the two [64,78,79,80,81]. EI refers to a set of emotional abilities that are supposed to foretell success in the real world above and beyond general intelligence [82,83]. Some findings have shown that high EI leads to better social relationships for children [84], better social relations for adults [85], and more positive perception of individuals from others [85]. High EI appears to influence familial relationships, intimate relationships [86], and academic achievement positively [87,88]. Furthermore, EI consistently seems to predict better social relations during work performance and in negotiations [89,90] and a better psychological well-being [91]. Go to: 3. The Pyramid of Emotional Intelligence: The Nine-Layer Model Τaking into consideration all the theories of the past concerning pyramids and layer models dealing with EI, we analyze the levels of our pyramid step by step (Figure 1), their characteristics, and the course of their development so as to conquer the upper levels, transcendence and emotional unity, as well as pointing out the significance of EI. Our model includes features from both constructions (the Ability EI and the Trait EI model) in a more hierarchical structure. The ability level refers to awareness (self and social) and to management. The level of trait refers to the mood associated with emotions and the tendency to behave in a certain way in emotional states considering other important elements that this construction includes as well. The EI pyramid is also based on the concepts of intrapersonal and interpersonal intelligences of Gardner [92,93]. An external file that holds a picture, illustration, etc. Object name is behavsci-08-00045-g001.jpg Figure 1 The emotional intelligence pyramid (9-layer model). 3.1. Emotional Stimuli Every day we receive a lot of information-stimuli from our environment. We need to incorporate this information and the various stimuli into categories because they help us to understand the world and the people that surround us better [94]. The direct stimulus of emotions is the result of the sensorial stimulus processing by the cognitive mechanisms [95,96,97]. When an event occurs, sensorial stimuli are received by the agent. The cognitive mechanisms process this stimulus and produce the emotional stimuli for each of the emotions that will be affected [98]. Emotional stimuli are processed by a cognitive mechanism that determines what emotion to feel and subsequently produce an emotional reaction which may influence the occurrence of the behavior. Emotional stimuli are generally prioritized in perception, are detected more quickly, and gain access to conscious awareness [99,100]. The emotional stimuli constitute the base of the pyramid of emotional intelligence pointing to the upper levels of it. 3.2. Emotion Recognition The next level of the pyramid after the emotional stimuli is the recognition of emotions simultaneously expressed at times. Accuracy is higher when emotions are both expressed and recognized. Emotion recognition includes the ability to accurately decode the expressions of others’ feelings, usually transmitted through non-verbal channels (i.e., the face, body, and voice). This ability is positively linked to social ability and interaction, as non-verbal behavior is a reliable source of information on the emotional states of others [101]. Elfenbein and Ambady commented that emotion recognition is the most “reliably validated component of emotional intelligence” linked to a variety of positive organizational outcomes [102]. The ability to express and recognize emotions in others is an important part of the daily human interaction and interpersonal relationships as it is a representation of a critical component of human socio-cognitive capacities [103]. 3.3. Self-Awareness Socrates mentions in his guiding principle, “know thyself”. Aristotle also mentioned “knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom”. These two ancient Greek aphorisms encompass the concept of self-awareness, a cognitive capacity, which is the following step in our pyramid after having conquered the previous two. Self-Awareness is having a clear perception of your personality, including your strengths, weaknesses, thoughts, beliefs, motives, and feelings [104]. As you develop self-awareness, you are able to change your thoughts which, in turn, allow you to change your emotions and eventually change your actions. Crisp and Turner [105] described self-awareness as a psychological situation in which people know their traits, feelings, and behaviors. Alternatively, it can be defined as the realization of oneself as an individual entity. Developing self-awareness is the first step to develop your EI. The lack of selfawareness in terms of understanding ourselves and having a sense of ourselves that has roots in our own values impedes our ability to self-manage and it is difficult, if not impossible, to know and to respond to the others’ feelings [61]. Daniel Goleman [106,107] recognized selfawareness as emotional consciousness, accurate self-esteem, and self-confidence. Knowing yourself means having the ability to understand your feelings, having an accurate selfassessment of your own strengths and weaknesses, and showing self-confidence. According to Goleman, self-awareness must be ahead of social awareness, self-management, and relationship management which are important factors of EI. 3.4. Self-Management Once you have clarified your emotions and the way they can affect the situations and other people, you are ready to move to the EQ area of self-management. Self-management allows you to control your reactions so that you are not driven by impulsive behaviors and feelings. With self-management, you become more flexible, more extroverted, and receptive, and at the same time less critical on situations and less reactionary to people’s attitudes. Moreover, you know more about what to do. When you have recognized your feelings and have accepted them, you are then able to manage them much better. The more you learn on the way to manage your emotions, the greater your ability will be to articulate them in a productive way when need be [108]. This does not mean that you must crush your negative emotions, but if you realize them, you can amend your behavior and make small or big changes to the way you react and manage your feelings even if the latter is negative. The second emotional intelligence (EQ) quadrant of self-management consists of nine key components: (1) emotional self-control; (2) integrity; (3) innovation and creativity; (4) initiative and prejudice to action; (5) resilience; (6) achievement guide; (7) stress management; (8) realistic optimism and (9) intentionality [80,106,107,109]. 3.5. Social Awareness—Empathy—The Discrimination of Emotions Since you have cultivated the ability to understand and control your own emotions, you are ready to move on to the next step of recognizing and understanding the emotions of people around you. Self-Management is a prerequisite for Social-Awareness. It is an expansion of your emotional awareness. Social Awareness refers to the way people handle relationships and awareness of others’ feelings, needs, and concerns [110]. The Social Awareness cluster contains three competencies: Empathy, Organizational Awareness, Service Orientation [107]. Being socially aware means that you understand how you react to different social situations, and effectively modify your interactions with other people so that you achieve the best results. Empathy is the most important and essential EQ component of social awareness and is directly related to self-awareness. It is the ability to put oneself in another’s place (or “shoes”), to understand him as a person, to feel him and to take into account this perspective related to this person or with any person at a time. With empathy, we can understand the feelings and thoughts of others from their own perspective and have an active role in their concerns [111]. The net result of social awareness is the ongoing development of social skills and a personal continuous improvement process [107,112,113]. Discrimination of emotions belongs to that level of the pyramid because it is a rather intellectual ability that gives people the capacity to discriminate with accuracy between different emotions and label them appropriately. The latter in relation to the other cognitive functions contributes to guide thinking and behavior [77]. 3.6. Social Skills—Expertise After having developed social awareness, the next level in the pyramid of emotional intelligence that helps raising our EQ is that of social skills. In emotional intelligence, the term social skills refers to the skills needed to handle and influence other people’s emotions effectively to manage interactions successfully. These abilities range from being able to tune into another person’s feelings and understand how they feel and think about things, to be a great collaborator and team player, to expertise at emotions of others and at negotiations. It is all about the ability to get the best out of others, to inspire and to influence them, to communicate and to build bonds with them, and to help them change, grow, develop, and resolve conflict [114,115,116]. Social skills under the branch of emotional intelligence can include Influence, Leadership, Developing Others, Communication, Change Catalyst, Conflict Management, Building Bonds, Teamwork, and Collaboration [61]. Expertise in emotions could be characterized as the ability to increase sensitivity to emotional parameters and the ability not only to accurately determine the relevance of emotional dynamics to negotiation but also the ability to strategically expose the emotions of the individual and respond to emotions stemming from others [117]. 3.7. Self-Actualization—Universality of Emotions As soon as all six of these levels have been met, the individual has reached the top of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs; Self-Actualization. Every person is capable and must have the will to move up to the level of self-actualization. Self-Actualization, according to Maslow [118,119,120], is the realization of personal potential, self-fulfillment, pursuing personal development and peak experiences. It is important to note that self-actualization is a continual process of becoming, rather than a perfect state one reaches such as a ‘happy ever after” [121]. Carl Rogers [122,123] also created a theory that included a “growth potential” whose purpose was to incorporate in the same way the “real self” and the “ideal self”, thereby cultivating the appearance of the “fully functioning person”. Self-actualization is one of the most important EI skills. It is a measure of your sense that you have a substantial personal commitment to life and that you are offering the gifts to your world that are most important for you. Reuven BarOn [124] illustrates the close relationship between emotional intelligence and selfactualization. His research led him to conclude that “you can actualize your potential capacity for personal growth only after you are socially and emotionally effective in meeting your needs and dealing with life in general”. Self-actualizers feel empathy and kinship towards humanity as a whole and therefore, that cultivates the universality of emotions, so that those they have emotional intelligence in one culture probably have emotional intelligence in another culture too and they have the ability to understand the difference of emotions and their meanings despite the fact that sometimes emotions are culturally dependent [125,126]. 3.8. Transcendence Maslow also proposed that people who have reached self-actualization will sometimes experience a state he referred to as “transcendence”. In the level of Transcendence, one helps others to self-actualize, find self-fulfillment, and realize their potential [127,128]. The emotional quotient is strong and those who have reached that level try to help other people understand and manage their own and others’ emotions too. Transcendence refers to the much higher and more comprehensive or holistic levels of human consciousness, by behaving and associating, as ends rather than as means, to ourselves, to important others, to human in general, to other species, to nature, and to the world [129]. Transcendence is strongly correlated with self-esteem, emotional well-being and global empathy. Self-transcendence is the experience of seeing yourself and the world in a way that is not impeded by the limits of one’s ego identity. It involves an increased sense of meaning and relevance to others and to the world [130,131]. In his perception of transcendence Plato affirmed the existence of absolute goodness that he characterized as something that cannot be described and it is only known through intuition. His ideas are divine objects that are transcendent of the world. Plato also speaks of gods, of God, of the cosmos, of the human soul, and of that which is real in material things as transcendental [132]. Self-transcendence can be expressed in various ways, behaviors and perspectives like the exchange of wisdom and emotions with others, the integration of physical/natural changes of aging, the acceptance of death as part of life, the interest in helping others and learning about the world, the ability to leave your losses behind, and the finding of spiritual significance in life [133]. 3.9. Emotional Unity Emotional unity is the final level in our pyramid of emotional intelligence. It is an intentionally positive oriented dynamic, in a sense that it aims towards reaching and keeping a dominance of emotions, which inform the subject that he or she is controlling the situation or the setting in an accepted shape. This reached level of emotional unity in the subject can be interpreted as an outcome of emotional intelligence [134]. The emotional unity is an internal harmony. In emotional unity one feels intense joy, peace, prosperity, and a consciousness of ultimate truth and the unity of all things. In a symbiotic world, what you do for yourself, you ultimately do for another. It all starts with our love for ourselves, so that we can then channel this important feeling to everything that exists around us [135]. Not only in human beings, but also in animals, plants, oceans, rocks, and so forth. All it takes is to see the spark of life and miracle in everything and be more optimistic. The point is that somehow, we are all interconnected, and the more we delve deeper our heart and follow it, the less likely it will be for us to do things that can harm others or the planet in general [136]. The others are not separate from us. Emotional unity emanates humility and empathy that bears with the imperfections of the other. Plato in Parmenides also talks about unity [137], Being, and One. As Parmenides writes: “Being is ungenerated and indestructible, whole, of one kind and unwavering, and complete. Nor was it, nor will it be, since now it is, all together, one, continuous…” [138,139]. Go to: 4. Cognitive and Metacognitive Processes in the Emotional Intelligence Pyramid Cognition encompasses processes such as attention, memory, evaluation, problem-solving language, and perception [140,141]. Cognitive processes use existing knowledge and generate new knowledge. Metacognition is defined as the ability to monitor and reflect upon one’s own performance and capabilities [142,143]. It is the ability of individuals to know their own cognitive functions in order to monitor and to control their learning process [144,145]. The idea of meta-cognition relies on the distinction between two types of cognitions: primary and secondary [146]. Metacognition includes a variety of elements and skills such as Metamemory, Self-Awareness, Self-Regulation, and Self-Monitoring [144,147]. Metacognition in Emotional Intelligence means that an individual perceives his/her emotional skills [148,149]. Its processes involve emotional-cognitive strategies such as awareness, monitoring, and self-regulation [150]. Apart from the primary emotion, a person can experience direct thoughts that accompany this emotion as people may have additional cognitive functions that monitor a given emotional situation [151], they may evaluate the relationship between emotion and judgment [152], and they may try to manage their emotional reaction [153] for the improvement of their own personality and that will motivate them to help other people for better interpersonal interactions. Applying the meta-knowledge to socio-emotional contexts should lead to the opportunity to learn to correct one’s emotional errors and to promote the future possibility of a proper response to the situation while maintaining and cultivating the relationship [154]. In the pyramid of Emotional Intelligence, to move from one layer to another, cognitive and metacognitive processes are occurred (Figure 2). An external file that holds a picture, illustration, etc. Object name is behavsci-08-00045-g002.jpg Figure 2 The cognitive and metacognitive processes to move from a layer to another. Go to: 5. Discussion & Conclusions Emotional Intelligence is a very important concept that has come back to the fore in the last decades and has been the subject of serious discussions and studies by many experts. The importance of general intelligence is neither underestimated nor changed, and this has been proven through many surveys and studies. On the other hand, however, we must also give emotional intelligence the place it deserves. The cultivation of emotional intelligence can contribute to and provide many positive benefits to people’s lives in accordance with studies, surveys, and with what has been already mentioned. When it comes to happiness and success in life, emotional intelligence (EQ) matters just as much as intellectual ability (IQ) [60]. Furthermore, it should be noted that despite the various discussions about emotional intelligence, studies have shown that emotional abilities that make up emotional intelligence are very important for the personal and social functioning of humans [83]. A core network of brain regions such as the amygdala and ventromedial prefrontal cortex is the key to a range of emotional abilities and plays a crucial role for human lesions [155]. Specific Emotional Intelligence components (Understanding Emotions and Managing Emotions) are directly related to the structural microarchitecture of major axial pathways [156]. With emotional intelligence you acknowledge, accept, and control your emotions and emotional reactions as well as those of other people. You learn about yourself and move on to the understanding of other people’s self. You learn to coexist better, which is very important since we are not alone in this world and because when we want to advance ourselves, and society as a whole, there must be cooperation and harmony. With emotional intelligence, you learn to insist, to control your impulses, to survive despite adversities and difficulties, to hope for and to have empathy. Emotional Intelligence provides you with a better inner world to cope with the outside world according to Trait EI [157]. It involves and engages higher cognitive functions such as attention, memory, regulation, reasoning, awareness, monitoring, and decision-making. The results show that negative mood and anticipated fear are two factors of the relationship between trait EI and risk-taking in decision-making processes among adults [158]. Research has also shown this positive correlation between emotional intelligence and cognitive processes and this demonstrates the important role that emotional intelligence plays with emotion and cognition, thus, empowering individuals and their personality and benefitting the whole society [159,160,161,162,163,164]. Αs we rise through the levels of the pyramid of emotional intelligence that we have presented, we step closer to its development to the fullest extent, to the universality of emotions, to emotional unity. The human being is good at trying to reach the last level of the pyramid because at each level he cultivates significant emotional, cognitive, and metacognitive skills that are important resources for the successes in one’s personal life, professional life, interpersonal relationships, and in life in general. Emotional intelligence is a skill that can be learned and developed [165,166]. The model of emotional intelligence has been created with a better distinct classification. It is a more structured evaluation and intervention model with hierarchical levels to indicate each level of emotional intelligence that everyone is at and with operating procedures to contribute to the strengthening of that level and progressive development of the individual to the next levels of emotional intelligence. It is a methodology for the further development and evolution of the individual. This model can have practical applications as an evaluation, assessment, and training tool in any aspect of life such as interpersonal relationships, work, health, special education, general education, and academic success. Researchers claim that an emotional mind is important for a good life as much as an intelligent mind and, in certain cases, it matters more [167]. The ultimate goal should be to develop Emotional Intelligence, do further research on the benefits of such an important capacity and the correlations between the layered Emotional Intelligence model and other variables. In this paper, we presented the pyramid of Emotional Intelligence as an attempt to create a new layer model based on emotional, cognitive, and metacognitive skills. In essence, each higher level of the pyramid is an improvement toward one’s personal growth and a higher state of self-regulation, self-organization, awareness, consciousness, attention, and motivation. Go to: Author Contributions A.S.D. and C.P. contributed equally in the conception, development, writing, editing, and analysis of this manuscript. The authors approved the final draft of the manuscript. Go to: Funding This research received no external funding. Go to: Conflicts of Interest The authors declare no conflict of interest. Go to: References 1. Mayer J.D., Salovey P., Caruso D.R. Emotional intelligence: New ability or eclectic traits? Am. Psychol. 2008;63:503–517. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.6.503. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 2. Cabello R., Sorrel M.A., Fernandez-Pinto I., Extremera N., Fernandez-Berrocal P. Age and gender differences in ability emotional intelligence in adults: A cross-sectional study. Dev. Psychol. 2016;52:1486–1492. doi: 10.1037/dev0000191. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 3. Costa A., Faria L. The impact of emotional intelligence on academic achievement: A longitudinal study in Portuguese secondary school. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2015;37:38–47. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2014.11.011. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 4. García-Sancho E., Salguero J.M., Fernández-Berrocal P. Relationship between emotional intelligence and aggression: Asystematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2014;19:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.007. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 5. Mayer J.D., Caruso D.R., Salovey P. The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emot. Rev. 2016;8:290–300. doi: 10.1177/1754073916639667. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 6. Naseem K. Job Stress and Employee Creativity: The mediating role of Emotional Intelligence. Int. J. Manag. Excell. 2017;9:1050–1058. doi: 10.17722/ijme.v9i2.340. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 7. Petrides K.V., Mikolajczak M., Mavroveli S., Sanchez-Ruiz M., Furnham A., Pérez-González J.C. Developments in trait emotional intelligence research. Emot. Rev. 2016;8:335–341. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650493. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 8. Smith K.B., Profetto-McGrath J., Cummings G.G. Emotional intelligence and nursing: An integrative literature review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2009;46:1624–1636. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.05.024. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 9. Busato V.V., Prins F.J., Elshout J.J., Hamaker C. Intellectual ability, learning style, personality, achievement motivation and academic success of psychology students in higher education. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2000;29:1057–1068. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00253-6. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 10. Kanazawa S. General intelligence as a domain-specific adaptation. Psychol. Rev. 2004;111:512–523. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.512. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 11. Sternberg R.J. The concept of intelligence and its role in lifelong learning and success. Am. Psychol. 1997;52:1030–1037. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.10.1030. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 12. Strenze T. Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research. Intelligence. 2007;35:401–426. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 13. Carroll J.B. Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1993. [Google Scholar] 14. McGrew K.S. CHC theory and the human cognitive abilities project: Standing on the shoulders of the giants of psychometric intelligence research. Intelligence. 2009;37:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2008.08.004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 15. Di Fabio A. Emotional Intelligence: New Perspectives and Applications. InTech; Rijeka, Croatia: 2011. [Google Scholar] 16. Gendron B. Why Emotional Capital Matters in Education and in Labour? Toward an Optimal Exploitation of Human Capital and Knowledge Management. Pantheon-Sorbonne University; Paris, France: 2004. [Google Scholar] 17. Matthews G., Zeidner M., Roberts R.D. Emotional Intelligence: Science and Myth. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA, USA: 2004. [Google Scholar] 18. Immordino-Yang M.H., Damasio A. We feel, therefore we learn: The relevance of affective and social neuroscience to education. Mind Brain Educ. 2007;1:3–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1751228X.2007.00004.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 19. Sale Z. Ph.D. Thesis. University of South Africa; Nov, 2014. The Relationship between Personality, Cognition and Emotional Intelligence. Master of Commerce in Industrial and Organisational Psychology. [Google Scholar] 20. Drigas A.S., Pappas M.A. The Consciousness-Intelligence-Knowledge Pyramid: An 8 × 8 Layer Model. Int. J. Recent Contrib. Eng. Sci. IT. 2017;5:14–25. doi: 10.3991/ijes.v5i3.7680. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 21. Heim M. The design of virtual reality. Body Soc. 1995;1:65–77. doi: 10.1177/1357034X95001003004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 22. Mackintosh N.J. IQ and Human Intelligence. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2011. [Google Scholar] 23. Sternberg R.J. Handbook of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar] 24. Eysenck H. Intelligence: A New Look. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 2018. [Google Scholar] 25. Spearman C. General Intelligence, Objectively Determined and Measured. Am. J. Psychol. 1904;15:201–292. doi: 10.2307/1412107. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 26. Spearman C. The theory of two factors. Psychol. Rev. 1914;21:101–115. doi: 10.1037/h0070799. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 27. Duncan J., Seitz R.J., Kolodny J., Bor D., Herzog H., Ahmed A., Newell F.N., Emslie H. A neural basis for general intelligence. Science. 2000;289:457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5478.457. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 28. Spearman C. The measurement of intelligence. Nature. 1927;120:577–578. doi: 10.1038/120577a0. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 29. Horn J.L., McArdle J.J. Understanding Human Intelligence since Spearman. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ, USA: 2007. pp. 205–249. [Google Scholar] 30. Thurstone L.L. The vectors of mind. Psychol. Rev. 1934;41:1–32. doi: 10.1037/h0075959. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 31. Thurstone L.L. Multiple-Factor Analysis. University of Chicago Press; Chicago, IL, USA: 1947. [Google Scholar] 32. Guilford J.P. The Nature of Human Intelligence. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 1967. [Google Scholar] 33. Richards R. Millennium as opportunity: Chaos, creativity, and Guilford’s Structure of Intellect Model. Creativity Res. J. 2001;13:249–265. doi: 10.1207/S15326934CRJ1334_03. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 34. Kvist A.V., Gustafsson J.E. The relation between fluid intelligence and the general factor as a function of cultural background: A test of Cattell’s investment theory. Intelligence. 2008;36:422–436. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2007.08.004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 35. Sternberg R.J. Beyond IQ: A Triarchic Theory of Human Intelligence. CUP Archive; Cambridge, UK: 1985. [Google Scholar] 36. Sternberg R.J. The theory of successful intelligence. Interam. J. Psychol. 2005;39:4–21. [Google Scholar] 37. Gardner H., Hatch T. Educational implications of the theory of multiple intelligences. Educ. Res. 1989;18:4–10. doi: 10.3102/0013189X018008004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 38. Morgan H. An analysis of Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligence. Roeper Rev. 1996;18:263–269. doi: 10.1080/02783199609553756. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 39. Darwin C., Prodger P. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Oxford University Press; New York, NY, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar] 40. Matsumoto D., Keltner D., Shiota M.N., O’Sullivan M., Frank M. Facial expressions of emotion. In: Lewis M., Haviland-Jones J.M., Barrett L.F., editors. Handbook of Emotions. Guilford; New York, NY, USA: 2008. pp. 211–234. [Google Scholar] 41. Farb N.A., Chapman H.A., Anderson A.K. Emotions: Form follows function. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2013;23:393–398. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2013.01.015. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 42. Bain A. Review of the Senses and the Intellect. Thoemmes Press; London, NY, USA: 1894. [Google Scholar] 43. Izard C.E. Four systems for emotion activation: Cognitive and noncognitive processes. Psychol. Rev. 1993;100:68–90. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.100.1.68. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 44. Hammond M. Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions. Springer; Boston, MA, USA: 2006. Evolutionary theory and emotions; pp. 368–385. [Google Scholar] 45. Nesse R.M. Evolutionary explanations of emotions. Hum. Nat. 1990;1:261–289. doi: 10.1007/BF02733986. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 46. Cannon W.B. The James-Lange theory of emotions: A critical examination and an alternative theory. Am. J. Psychol. 1927;39:106–124. doi: 10.2307/1415404. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 47. Lang P.J. The varieties of emotional experience: A meditation on James-Lange theory. Psychol. Rev. 1994;101:211–221. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.101.2.211. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 48. Dalgleish T. The emotional brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2004;5:583–589. doi: 10.1038/nrn1432. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 49. Reisenzein R. The Schachter theory of emotion: Two decades later. Psychol. Bull. 1983;94:239–264. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.94.2.239. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 50. Schachter S., Singer J. Cognitive, social, and physiological determinants of emotional state. Psychol. Rev. 1962;69:379–399. doi: 10.1037/h0046234. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 51. Smith C.A., Ellsworth P.C. Patterns of cognitive appraisal in emotion. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1985;48:813–838. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.48.4.813. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 52. Cohn M.A., Fredrickson B.L., Brown S.L., Mikels J.A., Conway A.M. Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion. 2009;9:361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0015952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 53. Fredrickson B.L. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-andbuild theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 2001;56:218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003066X.56.3.218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 54. Pekrun R., Muis K.R., Frenzel A.C., Götz T. Emotions at School. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 2017. [Google Scholar] 55. Ruvalcaba-Romero N.A., Fernández-Berrocal P., Salazar-Estrada J.G., Gallegos-Guajardo J. Positive emotions, self-esteem, interpersonal relationships and social support as mediators between emotional intelligence and life satisfaction. J. Behav. Health Soc. Issues. 2017;9:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jbhsi.2017.08.001. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 56. Ciarrochi J., Forgas J.P., Mayer J.D. Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life: A Scientific Inquiry. Psychology Press; London, UK: 2001. [Google Scholar] 57. Coetzer G.H. Emotional versus Cognitive Intelligence: Which is the better predictor of Efficacy for Working in Teams? J. Behav. Appl. Manag. 2016;16:116–133. [Google Scholar] 58. Kunnanatt J.T. Emotional intelligence: The new science of interpersonal effectiveness. Hum. Resour. Dev. Q. 2004;15:489–495. doi: 10.1002/hrdq.1117. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 59. Goleman D. Emotional intelligence: Issues in paradigm building In The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, Measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in Individuals, Groups, and Organizations. Volume 13. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2001. p. 26. [Google Scholar] 60. Goleman D.P. Emotional Intelligence: Why it Can Matter More than IQ for Character, Health and Lifelong Achievement. Bantam Books; New York, NY, USA: 1995. [Google Scholar] 61. Boyatzis R.E., Goleman D., Rhee K. Clustering competence in emotional intelligence: Insights from the Emotional Competence Inventory (ECI) In: Bar-On R., Parker J.D.A., editors. Handbook of Emotional Intelligence. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco, CA, USA: 2000. pp. 343–362. [Google Scholar] 62. Mayer J.D., Salovey P., Caruso D.R., Sitarenios G. Emotional intelligence as a standard intelligence. Emotion. 2001;1:232–242. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.1.3.232. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 63. Mestre J.M., MacCann C., Guil R., Roberts R.D. Models of cognitive ability and emotion can better inform contemporary emotional intelligence frameworks. Emot. Rev. 2016;8:322–330. doi: 10.1177/1754073916650497. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 64. Brackett M.A., Rivers S.E., Salovey P. Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass. 2011;5:88–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00334.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 65. Libbrecht N., Lievens F., Carette B., Côté S. Emotional intelligence predicts success in medical school. Emotion. 2014;14:64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0034392. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 66. Rezvani A., Chang A., Wiewiora A., Ashkanasy N.M., Jordan P.J., Zolin R. Manager emotional intelligence and project success: The mediating role of job satisfaction and trust. Int. J. Proj. Manag. 2016;34:1112–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.05.012. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 67. Mayer J.D., Roberts R.D., Barsade S.G. Human abilities: Emotional intelligence. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2008;59:507–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093646. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 68. Gutiérrez-Cobo M.J., Cabello R., Fernández-Berrocal P. The relationship between emotional intelligence and cool and hot cognitive processes: A systematic review. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2016;10:101. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2016.00101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 69. Salovey P., Mayer J.D. Emotional intelligence. Imagin. Cogn. Personal. 1990;9:185–211. doi: 10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 70. Mayer J.D., Salovey P., Caruso D.R., Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2. 0. Emotion. 2003;3:97–105. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.3.1.97. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 71. Mayer J.D. Emotion, intelligence, and emotional intelligence. In: Forgas J.P., editor. Handbook of Affect and Social Cognition. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ, USA: 2000. pp. 410–431. [Google Scholar] 72. Bar-On R. The Bar-On model of emotional-social intelligence (ESI) Psicothema. 2006;18:1– 28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] 73. Goleman D. Working with Emotional Intelligence. Bantam; New York, NY, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar] 74. Petrides K.V., Furnham A. Trait emotional intelligence: Psychometric investigation with reference to established trait taxonomies. Eur. J. Personal. 2001;15:425–448. doi: 10.1002/per.416. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 75. Petrides K.V., Pita R., Kokkinaki F. The location of trait emotional intelligence in personality factor space. Br. J. Psychol. 2007;98:273–289. doi: 10.1348/000712606X120618. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 76. Petrides K.V. Trait emotional intelligence theory. Ind. Organ. Psychol. 2010;3:136–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01213.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 77. Mayer J.D., Salovey P. Emotional intelligence and the construction and regulation of feelings. Appl. Prev. Psychol. 1995;4:197–208. doi: 10.1016/S0962-1849(05)80058-7. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 78. Mikolajczak M., Luminet O., Menil C. Predicting resistance to stress: Incremental validity of trait emotional intelligence over alexithymia and optimism. Psicothema. 2006;18:79–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] 79. O’Connor R.M., Jr., Little I.S. Revisiting the predictive validity of emotional intelligence: Self-report versus ability-based measures. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2003;35:1893–1902. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00038-2. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 80. Pérez J.C., Petrides K.V., Furnham A. Emotional Intelligence: An International Handbook. Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; Ashland, OH, USA: 2005. Measuring trait emotional intelligence; pp. 181–201. [Google Scholar] 81. Warwick J., Nettelbeck T. Emotional intelligence is …? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2004;37:1091–1100. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2003.12.003. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 82. Bar-On R. Emotional intelligence: An integral part of positive psychology. S. Afr. J. Psychol. 2010;40:54–62. doi: 10.1177/008124631004000106. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 83. Hogeveen J., Salvi C., Grafman J. ‘Emotional Intelligence’: Lessons from Lesions. Trends Neurosci. 2016;39:694–705. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.08.007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 84. Eisenberg N., Fabes R.A., Guthrie I.K., Reiser M. Dispositional emotionality and regulation: Their role in predicting quality of social functioning. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 2000;78:136– 157. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.1.136. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 85. Lopes P.N., Brackett M.A., Nezlek J.B., Schütz A., Sellin I., Salovey P. Emotional intelligence and social interaction. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2004;30:1018–1034. doi: 10.1177/0146167204264762. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 86. Brackett M.A., Warner R.M., Bosco J.S. Emotional intelligence and relationship quality among couples. Pers. Relationsh. 2005;12:197–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1350-4126.2005.00111.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 87. Aki O. Is emotional intelligence or mental intelligence more important in language learning. J. Appl. Sci. 2006;6:66–70. [Google Scholar] 88. Barchard K.A. Does emotional intelligence assist in the prediction of academic success? Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003;63:840–858. doi: 10.1177/0013164403251333. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 89. Elfenbein H.A., Der Foo M., White J., Tan H.H., Aik V.C. Reading your counterpart: The benefit of emotion recognition accuracy for effectiveness in negotiation. J. Nonverbal Behav. 2007;31:205–223. doi: 10.1007/s10919-007-0033-7. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 90. Rosete D., Ciarrochi J. Emotional intelligence and its relationship to workplace performance outcomes of leadership effectiveness. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2005;26:388–399. doi: 10.1108/01437730510607871. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 91. Gohm C.L., Corser G.C., Dalsky D.J. Emotional intelligence under stress: Useful, unnecessary, or irrelevant? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2005;39:1017–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.03.018. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 92. Gardner H.E. Intelligence Reframed: Multiple Intelligences for the 21st Century. Hachette UK; London, UK: 2000. [Google Scholar] 93. Gardner H. Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. Basic Books; New York, NY, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar] 94. Brosch T., Pourtois G., Sander D. The perception and categorisation of emotional stimuli: A review. Cogn. Emot. 2010;24:377–400. doi: 10.1080/02699930902975754. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 95. Mayer J.D., DiPaolo M., Salovey P. Perceiving affective content in ambiguous visual stimuli: A component of emotional intelligence. J. Personal. Assess. 1990;54:772–781. doi: 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674037. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 96. Isomura T., Nakano T. Automatic facial mimicry in response to dynamic emotional stimuli in five-month-old infants. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2016;283 doi: 10.1098/rspb.2016.1948. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 97. Vuilleumier P. How brains beware: Neural mechanisms of emotional attention. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2005;9:585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.10.011. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 98. Moors A. Cognition and Emotion. Psychology Press; London, UK: 2010. Theories of emotion causation: A review; pp. 11–47. [Google Scholar] 99. Mitchell D.G., Greening S.G. Conscious perception of emotional stimuli: Brain mechanisms. Neuroscientist. 2012;18:386–398. doi: 10.1177/1073858411416515. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 100. Okon-Singer H., Lichtenstein-Vidne L., Cohen N. Dynamic modulation of emotional processing. Biol. Psychol. 2013;92:480–491. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.05.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 101. Rubin R.S., Munz D.C., Bommer W.H. Leading from within: The effects of emotion recognition and personality on transformational leadership behavior. Acad. Manag. J. 2005;48:845–858. doi: 10.5465/AMJ.2005.18803926. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 102. Elfenbein H.A., Ambady N. On the universality and cultural specificity of emotion recognition: A meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2002;128:203–235. doi: 10.1037/00332909.128.2.203. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 103. Lewis G.J., Lefevre C.E., Young A.W. Functional architecture of visual emotion recognition ability: A latent variable approach. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2016;145:589–602. doi: 10.1037/xge0000160. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 104. Ferrari M.D., Sternberg R.J. Self-Awareness: Its Nature and Development. Guilford Press; New York, NY, USA: 1998. [Google Scholar] 105. Crisp R.J., Turner R.N. Essential Social Psychology. Sage; Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: 2014. [Google Scholar] 106. Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence: Why it Can Matter More Than IQ. Bloomsbury Publishing; London, UK: 1996. [Google Scholar] 107. Goleman D. The Emotionally Intelligent Workplace: How to Select for, Measure, and Improve Emotional Intelligence in Individuals, Groups, and Organizations. Volume 1. John Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2001. An EI-based theory of performance; pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar] 108. Sunindijo R.Y., Hadikusumo B.H., Ogunlana S. Emotional intelligence and leadership styles in construction project management. J. Manag. Eng. 2007;23:166–170. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0742-597X(2007)23:4(166). [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 109. Fernández-Berrocal P., Extremera N. Emotional intelligence: A theoretical and empirical review of its first 15 years of history. Psicothema. 2006;18:7–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] 110. Boyatzis R.E. Competencies as a behavioral approach to emotional intelligence. J. Manag. Dev. 2009;28:749–770. doi: 10.1108/02621710910987647. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 111. Ioannidou F., Konstantikaki V. Empathy and emotional intelligence: What is really about? Int. J. Caring Sci. 2008;1:118. [Google Scholar] 112. Bradberry T., Greaves J. Emotional Intelligence 2.0. TalentSmart; San Diego, CA, USA: 2009. [Google Scholar] 113. Zeidner M., Matthews G., Roberts R.D. Emotional intelligence in the workplace: A critical review. Appl. Psychol. 2004;53:371–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2004.00176.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 114. Adkins J.H. Master’s Theses. University of Nevada; Las Vegas, Nevada: 2004. Investigating Emotional Intelligence and Social Skills in Home Schooled Students. [Google Scholar] 115. Gresham F.M., Elliott S.N., Vance M.J., Cook C.R. Comparability of the Social Skills Rating System to the Social Skills Improvement System: Content and psychometric comparisons across elementary and secondary age levels. Sch. Psychol. Q. 2011;26:27–44. doi: 10.1037/a0022662. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 116. Schutte N.S., Malouff J.M., Bobik C., Coston T.D., Greeson C., Jedlicka C., Rhodes E., Wendorf G. Emotional intelligence and interpersonal relations. J. Soc. Psychol. 2001;141:523– 536. doi: 10.1080/00224540109600569. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 117. Potworowski G., Kopelman S. Developing evidence-based expertise in emotion management: Strategically displaying and responding to emotions in negotiations. Negot. Confl. Manag. Res. 2007;1:333–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-4716.2008.00020.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 118. Maslow A.H. A Theory of Human Motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943;50:370–396. doi: 10.1037/h0054346. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 119. Maslow A.H. Motivation and Personality. Harper and Row; New York, NY, USA: 1954. [Google Scholar] 120. Maslow A.H. Perceiving, Behaving, Becoming: A New Focus for Education. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development; Washington, DC, USA: 1962. Some basic propositions of a growth and self-actualization psychology; pp. 34–49. [Google Scholar] 121. Hoffman E. In: The Right to be Human: A Biography of Abraham Maslow. Jeremy P., editor. Tarcher, Inc.; New York, NY, USA: 1988. [Google Scholar] 122. Rogers C. Client-Centered Therapy: Its Current Practice, Implications and Theory. Constable; London, UK: 1951. [Google Scholar] 123. Rogers C. A Theory of Therapy, Personality and Interpersonal Relationships as Developed in the Client-Centered Framework. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY, USA: 1959. [Google Scholar] 124. Bar-On R. Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life: A Scientific Inquiry. Psychology Press; London, UK: 2001. Emotional intelligence and self-actualization; pp. 82–97. [Google Scholar] 125. Elfenbein H.A., Ambady N. Predicting workplace outcomes from the ability to eavesdrop on feelings. J. Appl. Psychol. 2002;87:963–971. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.87.5.963. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 126. Lutz C., White G.M. The anthropology of emotions. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 1986;15:405– 436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.15.100186.002201. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 127. Huitt W. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University; Valdosta, GA, USA: 2001. Motivation to learn: An overview; p. 12. [Google Scholar] 128. Huitt W. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta State University; Valdosta, GA, USA: 2004. [(accessed on 24 April 2006)]. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Available online: http://chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/regsys/maslow.html. [Google Scholar] 129. Maslow A.H. The Farther Reaches of Human Nature. Arkana/Penguin Books; New York, NY, USA: 1971. [Google Scholar] 130. Van Cappellen P., Rimé B. Religion, Personality, and Social Behavior. Taylor and Francis; Abingdon, UK: 2014. Positive emotions and self-transcendence; pp. 123–145. [Google Scholar] 131. Venter H.J. Self-Transcendence: Maslow’s Answer to Cultural Closeness. J. Innov. Manag. 2017;4:3–7. [Google Scholar] 132. Gregory M.J. Myth and Transcendence in Plato. Thought. 1968;43:273–296. doi: 10.5840/thought196843220. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 133. Levenson M.R., Jennings P.A., Aldwin C.M., Shiraishi R.W. Self-transcendence: Conceptualization and measurement. Int. J. Aging Hum. Dev. 2005;60:127–143. doi: 10.2190/XRXM-FYRA-7U0X-GRC0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 134. Biela A. Paradigm of Unity as a Prospect for Research and Treatment in Psychology. J. Perspect. Econ. Political Soc. Integr. 2014;19:207–227. doi: 10.2478/v10241-012-0018-2. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 135. Kristjánsson K. Aristotle, Emotions, and Education. Routledge; Abingdon, UK: 2016. [Google Scholar] 136. Bateson G. Mind and Nature: A Necessary Unity. Dutton; New York, NY, USA: 1979. p. 238. [Google Scholar] 137. Brown E. Plato and the Divided Self. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2012. The Unity of the Soul in Plato’s Republic; pp. 53–73. [Google Scholar] 138. Burnet J. Early Greek Philosophy. Kessinger Publishing; Whitefish, MT, USA: 1908. [Google Scholar] 139. Cornford F.M. Plato and Parmenides: Parmenides’ Way of Truth and Plato’s Parmenides. The Bobbs-Merrill Company, Inc.; Indianapolis, IN, USA: 1939. [Google Scholar] 140. Best J.B. Cognitive Psychology. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; Belmont, CA, USA: 1999. [Google Scholar] 141. Coren S. Sensation and Perception. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; Hoboken, NJ, USA: 2003. [Google Scholar] 142. Dunlosky J., Metcalfe J. Metacognition. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: 2008. [Google Scholar] 143. Flavell J.H. Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: A new area of cognitive– developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 1979;34:906–911. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 144. Caro Pineres M.F., Jimenez Builes J.A. Analysis of models and metacognitive architectures in intelligent systems. Dyna. 2013;80:50–59. [Google Scholar] 145. Cox M.T. Field review: Metacognition in computation: A selected research review. Artif. Intell. 2005;169:104–141. doi: 10.1016/j.artint.2005.10.009. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 146. McGuire C.V., McGuire W.J. The Content, Structure, and Operation of Thought Systems. Psychology Press; London, UK: 2014. The content, structure, and operation of thought systems; pp. 9–86. [Google Scholar] 147. Vockell E. Educational Psychology: A Practical Approach. Allyn & Bacon; Boston, MA, USA: 2009. Zetacognitive skills. [Google Scholar] 148. Briñol P., Petty R.E., Rucker D.D. The role of meta-cognitive processes in emotional intelligence. Psicothema. 2006;18:26–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] 149. Elipe P., Mora-Merchán J.A., Ortega-Ruiz R., Casas J.A. Perceived emotional intelligence as a moderator variable between cybervictimization and its emotional impact. Front. Psychol. 2015;6:486. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00486. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 150. Wheaton A. Metacognition and emotional intelligence. Aust. Educ. Lead. 2012;34:38–41. [Google Scholar] 151. Scheier M.F., Carver C.S. Self-consciousness, outcome expectancy, and persistence. J. Res. Personal. 1982;16:409–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-6566(82)90002-2. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 152. Mayer J.D., Volanth A.J. Cognitive involvement in the mood response system. Motiv. Emot. 1985;9:261–275. doi: 10.1007/BF00991831. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 153. Isen A.M. Toward Understanding the Role of Affect in Cognition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ, USA: 1984. [Google Scholar] 154. Kelly K.J., Metcalfe J. Metacognition of emotional face recognition. Emotion. 2011;11:896–906. doi: 10.1037/a0023746. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 155. Operskalski J.T., Paul E.J., Colom R., Barbey A.K., Grafman J.H. Lesion mapping the fourfactor structure of emotional intelligence. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015;9:649. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 156. Pisner D.A., Smith R., Alkozei A., Klimova A., Killgore W.D. Highways of the emotional intellect: White matter microstructural correlates of an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence. Soc. Neurosci. 2017;12:253–267. doi: 10.1080/17470919.2016.1176600. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 157. Szczygieł D., Mikolajczak M. Why are people high in emotional intelligence happier? They make the most of their positive emotions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017;117:177–181. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.05.051. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 158. Panno A., Anna Donati M., Chiesi F., Primi C. Trait emotional intelligence is related to risktaking through negative mood and anticipated fear. Soc. Psychol. 2015;46:361–367. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000247. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 159. Killgore W.D., Yurgelun-Todd D.A. Neural correlates of emotional intelligence in adolescent children. Cogn.Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2007;7:140–151. doi: 10.3758/CABN.7.2.140. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 160. Megías A., Gutiérrez-Cobo M.J., Gómez-Leal R., Cabello R., Fernández-Berrocal P. Performance on emotional tasks engaging cognitive control depends on emotional intelligence abilities: An ERP study. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16446. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16657-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 161. Mitchell R.L., Phillips L.H. The overlapping relationship between emotion perception and theory of mind. Neuropsychologia. 2015;70:1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.02.018. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 162. Panno A. Trait emotional intelligence is related to risk taking when adolescents make deliberative decisions. Games. 2016;7:23. doi: 10.3390/g7030023. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 163. Rezaeian M., Abdollahi M., Shahgholian M. The Role of Reading Mind from Eyes, Mental Culture and Emotional Intelligence in Social Decision-Making. Int. J. Behav. Sci. 2017;11:90–95. [Google Scholar] 164. Sevdalis N., Petrides K.V., Harvey N. Trait emotional intelligence and decision-related emotions. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2007;42:1347–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.012. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 165. Brackett M.A., Rivers S.E., Reyes M.R., Salovey P. Using emotional literacy to improve classroom social-emotional processes; Proceedings of the William T. Grant Foundation/Spencer Foundation Grantees Meeting; Washington, DC, USA. 2010. [Google Scholar] 166. Nelis D., Quoidbach J., Mikolajczak M., Hansenne M. Increasing emotional intelligence: (How) is it possible? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2009;47:36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.046. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] 167. Nelson D., Nelson K., Low G. Proceedings of the World Conference on Children’s Rights and Education in the 21st Century. Texas A&M University; Corpus Christi, TX, USA: 2006. Emotional intelligence: Educating the right mind for the 21st century. [Google Scholar] Un nuevo modelo en capas sobre la inteligencia emocional Athanasios S. Drigas1, * y Chara Papoutsi2 Información del autor Notas del artículo Información de derechos de autor y de licencia Exención de responsabilidad Este artículo ha sido citado por otros artículos en PMC. Ir: Resumen La inteligencia emocional (IE) ha sido un tema importante y controvertido en las últimas décadas. Su importancia y su correlación con muchos dominios de la vida lo han convertido en un tema de estudio experto. La IE es el timón para sentir, pensar, aprender, resolver problemas y tomar decisiones. En este artículo, presentamos un enfoque emocional-cognitivo basado en el proceso de obtención de inteligencia emocional y, por lo tanto, sugerimos una pirámide de inteligencia emocional de nueve capas y el desarrollo gradual para alcanzar la cima de la IE. Palabras clave: inteligencia, emociones, conciencia, gestión, inteligencia emocional. Ir: 1. Introducción Muchas personas malinterpretan sus propias reacciones emocionales, no controlan los arrebatos emocionales o actúan de manera extraña bajo diversas presiones, lo que resulta en consecuencias perjudiciales para ellos mismos, para los demás y para la sociedad. Otras personas tienen una mayor capacidad para realizar un procesamiento sofisticado de información sobre emociones y estímulos relevantes para la emoción y para usar esta información como una guía para sus propios pensamientos y comportamientos y para otros, en general [1]. La inteligencia emocional (IE) es de gran interés para los científicos e investigadores. Se siguen realizando estudios, desde el pasado hasta hoy, sobre la naturaleza de la inteligencia emocional, su medida, su estructura, sus efectos positivos y negativos y su relación con muchos campos de investigación [2,3,4,5,6,7 , 8]. Su influencia en la vida diaria a corto y largo plazo también es importante Ir: 2. Hallazgos de la investigación 2.1. Teorias de la inteligencia La estructura, la naturaleza y las características de la inteligencia humana han sido discutidas y han sido objeto de debate desde los tiempos de Platón y Aristóteles, hace al menos mil años. Platón definió la inteligencia como una "melodía de aprendizaje" [21,22]. Bajo este concepto, Platón y Aristóteles exponen los tres componentes de mente y alma: intelecto, sentimiento y voluntad [23]. La palabra "inteligencia" viene de dos palabras latinas: intellegentia e ingenium. La primera palabra, considerada en la forma en que Cicerón usó el término, significa "comprensión" y "conocimiento". La segunda palabra significa "predisposición natural" o "habilidad" [24]. En varios puntos de la historia reciente, los investigadores han propuesto diferentes definiciones para explicar la naturaleza de la inteligencia [22]. Las siguientes son algunas de las teorías de inteligencia más importantes que han surgido en los últimos 100 años. Charles Spearman [25] desarrolló la teoría de los dos factores de la inteligencia utilizando un análisis factorial de datos (un método estadístico) para mostrar que las correlaciones positivas entre los exámenes mentales se debían a un agente subyacente común. Spearman sugirió que la teoría de los dos factores tenía dos componentes. El primero fue la inteligencia general, g, que afectó el desempeño de una persona en todas las tareas mentales y apoyó todas las tareas intelectuales y las capacidades intelectuales [25,26]. Spearman creía que los resultados en todos los ensayos se correlacionaban positivamente, lo que subyace a la importancia de la inteligencia general [25, 27]. El segundo agente que Spearman encontró fue el factor específico, s. El factor específico se asoció con las capacidades únicas que requería una prueba en particular, por lo que difería de una prueba a otra [25, 26]. Con respecto a g, Spearman vio que los individuos tenían una inteligencia más o menos general, mientras que s variaba de persona a persona en un trabajo [28]. Spearman y sus seguidores dieron mucha más importancia a la inteligencia general que al agente específico [25, 29]. En 1938, el psicólogo estadounidense Louis L. Thurstone sugirió que la inteligencia no era un factor general, sino un pequeño conjunto de factores independientes que tenían igual importancia. Thurstone formuló un modelo de inteligencia centrado en las "Habilidades mentales primarias" (PMA), que eran grupos independientes de inteligencia que diferentes individuos poseían en diversos grados. Para detectar estas habilidades, Thurstone y su esposa, Thelma, pensaron en un total de 56 exámenes. Pasaron el paquete de pruebas a 240 estudiantes y analizaron los puntajes obtenidos de las pruebas con nuevos métodos del método de análisis de Thurstone. Thurstone reconoció siete habilidades cognitivas primarias: (1) comprensión verbal, la capacidad de entender las nociones de las palabras; (2) flexibilidad verbal, la velocidad con la que se maneja el material verbal, como en la producción de rimas; (3) número, la capacidad aritmética; (4) memoria, la capacidad de recordar palabras, letras, números e imágenes; (5) la velocidad perceptiva, la capacidad de discernir y distinguir rápidamente los detalles visuales y la capacidad de percibir las similitudes y las diferencias entre los objetos mostrados; (6) el razonamiento inductivo, la extracción de ideas generales y reglas de información específica; y (7) visualización espacial, la capacidad de visualizar con la mente y manejar objetos en tres dimensiones [30,31] Joy Paul Guilford extendió el trabajo de Thurstone y dedicó su vida a crear el modelo para la estructura de la inteligencia. SI (Estructura de la teoría del intelecto, 1955) contiene tres dimensiones: funciones del pensamiento, contenido del pensamiento y productos del pensamiento. Guilford describió 120 tipos diferentes de inteligencia y 150 combinaciones posibles. También descubrió la importante distinción entre pensamiento convergente y divergente. La habilidad convergente da como resultado lo bien que uno sigue las instrucciones, se adhiere a las reglas y lo intenta. La habilidad divergente disminuye dependiendo de si uno sigue o no las instrucciones o si tiene muchas preguntas, y generalmente significa que uno está haciendo mal las pruebas estándar [32,33]. Los modelos Cattell-Horn Gf-Gc y Carroll Three-Stratum son modelos psicométricos consensuales que nos ayudan a comprender la construcción de la inteligencia humana. Aplican nuevos métodos de análisis y, según estos análisis, hay dos tipos básicos de inteligencia general: inteligencia fluida (gf) e inteligencia cristalizada (gc). La inteligencia fluida representa la base biológica de la inteligencia. La rapidez con que alguien piensa y lo bien que recuerda son elementos de inteligencia fluida. Estas cifras aumentan en la edad adulta, pero a medida que envejecemos, disminuyen. La inteligencia fluida permite a una persona pensar y actuar rápidamente, resolver nuevos problemas y codificar memorias a corto plazo. La inteligencia cristalizada, por otro lado, es el conocimiento y las habilidades adquiridas a través del proceso de aprendizaje y la experiencia. Las habilidades cristalizadas provienen del aprendizaje y la lectura y se reflejan en pruebas de conocimiento, información general, uso del lenguaje (vocabulario) y una amplia variedad de habilidades. Mientras las oportunidades de aprendizaje estén disponibles, la inteligencia cristalizada puede aumentar indefinidamente durante la vida de una persona [14,34]. En la década de 1980, el psicólogo estadounidense Robert Sternberg propuso una teoría de la inteligencia con la que trató de extender la noción tradicional de inteligencia. Sternberg observó que las pruebas mentales a las que se someten las personas para diversas mediciones de inteligencia a menudo son inexactas y, en ocasiones, inadecuadas para predecir el rendimiento o el éxito real. Hay personas que obtienen buenos resultados en las pruebas pero no tan bien en situaciones reales. Igualmente, ocurrió lo contrario. De acuerdo con la teoría de la inteligencia triarchic (en tres partes) de Sternberg, la inteligencia consta de tres partes principales: inteligencia analítica, inteligencia creativa e inteligencia práctica. La inteligencia analítica se refiere a las habilidades de resolución de problemas, la inteligencia creativa incluye la capacidad de manejar nuevas situaciones utilizando experiencias pasadas y habilidades actuales, y la inteligencia práctica se refiere a la capacidad de adaptarse a nuevas situaciones y entornos [35,36] En 1983, el psicólogo Howard Gardner presentó su teoría de las inteligencias múltiples (MI), que en ese momento era un tema fundamental en la educación y un tema controvertido entre los psicólogos. Según Gardner, la noción de inteligencia definida a través de varias pruebas mentales era limitada y no representaba las dimensiones reales de la inteligencia ni todas las áreas en las que una persona puede sobresalir y tener éxito. Gardner argumentó que no solo hay un tipo de inteligencia general, sino que existen inteligencias múltiples y cada una es parte de un sistema independiente en el cerebro. La teoría describe ocho tipos de "inteligente": inteligencia lingüística ("palabra inteligente"), inteligencia lógica-matemática ("número / razonamiento inteligente"), inteligencia espacial ("imagen inteligente"), inteligencia corporal-cinestésica ("cuerpo inteligente" ), Inteligencia musical ("música inteligente"), Inteligencia interpersonal ("gente inteligente"), Inteligencia intrapersonal ("auto inteligente") e Inteligencia naturalista ("naturaleza inteligente") [37,38]. 2.2. Emociones Según Darwin, todas las personas, independientemente de su raza o cultura, expresan emociones utilizando su rostro y cuerpo de una manera similar como parte de nuestra herencia evolutiva [39, 40]. La emoción a menudo se define como un sentimiento complejo que resulta en cambios físicos y psicológicos que afectan el pensamiento y el comportamiento. Las emociones incluyen sentimientos, pensamientos, activación del sistema nervioso, cambios fisiológicos y cambios de comportamiento, como las expresiones faciales. Las emociones parecen dominar muchos aspectos de nuestras vidas, ya que tenemos que reconocer y responder a eventos importantes relacionados con la supervivencia y / o el mantenimiento de la prosperidad y, por lo tanto, las emociones cumplen varias funciones [41]. Las emociones también son reconocidas como una de las tres o cuatro categorías fundamentales de operaciones mentales. Estas categorías incluyen motivación, emoción, cognición y conciencia [42]. La mayoría de las principales teorías de la emoción están de acuerdo en que los procesos cognitivos son una fuente muy importante de emociones y que los sentimientos comprenden un poderoso sistema motivacional que influye significativamente en la percepción, la cognición, la confrontación y la creatividad [43]. Los investigadores han estado estudiando cómo y por qué las personas sienten emociones durante mucho tiempo, por lo que se han propuesto varias teorías. Estas incluyen teorías evolutivas [44,45], la Teoría de James-Lange [46,47], Teoría de Cannon-Bard [48], Teoría de los dos factores de Schacter and Singer [49,50] y Evaluación cognitiva [51]. 2.3. Inteligencia emocional Cualquiera puede enojarse, eso es fácil. Pero estar enojado con la persona correcta, en el grado correcto, en el momento adecuado, con el propósito correcto y de la manera correcta, esto no es fácil. —Aristotle, La Ética a Nicómaco Una investigación exhaustiva ha indicado el importante papel que desempeñan las emociones en nuestras vidas en muchos campos [52,53,54,55]. Los investigadores han encontrado que la Inteligencia Emocional es igual o, a veces, mucho más importante que I.Q [56,57,58,59,60]. La emoción y la inteligencia están fuertemente vinculadas [61,62,63]. Si está al tanto de sus propios sentimientos y los de los demás, esto lo ayudará a manejar los comportamientos y las relaciones y predecir el éxito en muchos sectores [64,65,66]. La inteligencia emocional es la capacidad de identificar, comprender y usar emociones de manera positiva para manejar la ansiedad, comunicarse bien, empatizar, superar problemas, resolver problemas y manejar conflictos. De acuerdo con el modelo Ability EI, es la percepción, evaluación y manejo de las emociones en uno mismo y en los demás [67]. La Inteligencia Emocional (EI), o la capacidad de percibir, usar, comprender y regular las emociones, es un concepto relativamente nuevo que intenta conectar la emoción y la cognición [68]. La inteligencia emocional apareció por primera vez en el concepto de "inteligencia social" de Thorndike en 1920 y luego del psicólogo Howard Gardner, quien en 1983 recomendó la teoría de la inteligencia múltiple, argumentando que la inteligencia incluye ocho formas. Los psicólogos estadounidenses Peter Salovey y John Mayer, quienes juntos presentaron el concepto en 1990 [69], definen la inteligencia emocional "como la capacidad de controlar las emociones propias y ajenas, de discriminar entre ellas y de utilizar la información para guiar el pensamiento y las acciones. ". Las personas que han desarrollado su inteligencia emocional tienen la capacidad de usar sus emociones para dirigir los pensamientos y el comportamiento y para comprender sus propios sentimientos y los de los demás con precisión. Daniel Goleman, un escritor estadounidense, psicólogo y periodista científico, reveló el concepto de IE en su libro titulado "Inteligencia emocional" [58,59,60]. Extendió el concepto para incluir la competencia social general. Goleman sugirió que la IE es indispensable para el éxito de la vida. Mayer y Salovey sugirieron que la IE es una capacidad cognitiva, que está separada pero también asociada con la inteligencia general. Específicamente, Mayer, Salovey, Caruso y Sitarenios [70] sugirieron que la inteligencia emocional consiste en cuatro dimensiones de habilidad: (1) percepción de la emoción (es decir, la capacidad de detectar emociones en caras, imágenes, música, etc.); (2) facilitar el pensamiento con la emoción (es decir, la capacidad de aprovechar la información emocional en el pensamiento de uno); (3) comprensión de las emociones (es decir, la capacidad de comprender información emocional); y (4) manejar las emociones (es decir, la capacidad de manejar las emociones para el desarrollo personal e interpersonal). Estas habilidades están organizadas jerárquicamente para que la emoción perceptiva tenga un papel clave que facilite el pensamiento, la comprensión de las emociones y el manejo de las emociones. Estas ramas surgen de habilidades básicas de orden superior, que se desarrollan a medida que una persona madura [67,71]. Según Bar-On, la inteligencia emocional y social está compuesta por habilidades, habilidades y facilitadores sociales y emocionales. Todos estos elementos están interrelacionados y trabajan juntos. Desempeñan un papel clave en la eficacia con la que nos entendemos a nosotros mismos y a los demás, a la facilidad con que nos expresamos, pero también a la forma en que abordamos las demandas diarias [72]. Daniel Goleman (1998) define la Inteligencia Emocional / Cociente como la capacidad de reconocer nuestros propios sentimientos y los de los demás, de motivarnos y de manejar nuestras emociones para tener lo mejor para nosotros y para nuestras relaciones. La inteligencia emocional describe capacidades diferentes, pero complementarias, de la inteligencia académica. El mismo autor introdujo el concepto de inteligencia emocional y señaló que se compone de veinticinco elementos que posteriormente se compilaron en cinco grupos: autoconciencia, autorregulación, motivación, empatía y habilidades sociales [61,73]. Petrides y Furnham (2001) desarrollaron el modelo de Inteligencia Emocional del Rasgo, que es una combinación de habilidades y estados de ánimo auto-percibidos relacionados emocionalmente que se encuentran en los niveles más bajos de la jerarquía de la personalidad y se evalúan a través de cuestionarios y escalas de calificación [74]. El rasgo de la IE se refiere esencialmente a nuestras percepciones de nuestro mundo emocional interno. Una etiqueta alternativa para el mismo constructo es el rasgo de autoeficacia emocional. Las personas con altos rangos de la IE creen que están "en contacto" con sus sentimientos y pueden regularlos de una manera que promueva la prosperidad. Estas personas pueden disfrutar de niveles más altos de felicidad. El rasgo del dominio de muestreo de características de la IE tiene como objetivo proporcionar una cobertura completa de los aspectos emocionales de la personalidad. El Rasgo EI rechaza la idea de que las emociones pueden ser objetivadas artificialmente para ser clasificadas con precisión a lo largo de las líneas de CI [75]. El dominio de muestreo adulto del rasgo EI contiene 15 facetas: Adaptabilidad, Asertividad, Percepción de la emoción (uno mismo y otros), Expresión de la emoción, Manejo de la emoción (de otros), Regulación de la emoción, Impulsividad (bajo), Relaciones, Autoestima, Auto-motivación. , Conciencia social, Manejo del estrés, Empatía del rasgo, Felicidad del rasgo y Optimismo del rasgo [76]. La investigación sobre inteligencia emocional se ha dividido en dos áreas distintas de perspectivas en términos de conceptualizar las competencias emocionales y sus medidas. Existe la habilidad del modelo EI [77] y el rasgo EI [74]. La evidencia de investigación ha apoyado de manera consistente esta distinción al revelar bajas correlaciones entre los dos [64,78,79,80,81]. La IE se refiere a un conjunto de habilidades emocionales que supuestamente predicen el éxito en el mundo real más allá de la inteligencia general [82,83]. Algunos hallazgos han demostrado que una alta IE conduce a mejores relaciones sociales para los niños [84], mejores relaciones sociales para los adultos [85] y una percepción más positiva de los individuos de los demás [85]. La alta IE parece influir positivamente en las relaciones familiares, las relaciones íntimas [86] y el rendimiento académico [87,88]. Además, la IE parece predecir consistentemente mejores relaciones sociales durante el desempeño laboral y en las negociaciones [89,90] y un mejor bienestar psicológico [91]. Ir: 3. La pirámide de la inteligencia emocional: el modelo de nueve capas Teniendo en cuenta todas las teorías del pasado concernientes a las pirámides y los modelos de capas que tratan con la IE, analizamos los niveles de nuestra pirámide paso a paso (Figura 1), sus características y el curso de su desarrollo para conquistar los niveles superiores. trascendencia y unidad emocional, además de señalar el significado de la IE. Nuestro modelo incluye características de ambas construcciones (el modelo Ability EI y el modelo Trait EI) en una estructura más jerárquica. El nivel de habilidad se refiere a la conciencia (auto y social) y a la gestión. El nivel de rasgo se refiere al estado de ánimo asociado con las emociones y la tendencia a comportarse de cierta manera en los estados emocionales, considerando otros elementos importantes que esta construcción también incluye. La pirámide de la IE también se basa en los conceptos de inteligencias intrapersonales e interpersonales de Gardner [92,93]. Un archivo externo que contiene una imagen, ilustración, etc. El nombre del objeto es behavsci-08-00045-g001.jpg Figura 1 La pirámide de la inteligencia emocional (modelo de 9 capas). 3.1. Estímulos emocionales Todos los días recibimos muchos estímulos informativos de nuestro entorno. Necesitamos incorporar esta información y los diversos estímulos en categorías porque nos ayudan a entender el mundo y las personas que nos rodean mejor [94]. El estímulo directo de las emociones es el resultado del procesamiento sensorial por los mecanismos cognitivos [95,96,97]. Cuando ocurre un evento, el agente recibe estímulos sensoriales. Los mecanismos cognitivos procesan este estímulo y producen los estímulos emocionales para cada una de las emociones que serán afectadas [98]. Los estímulos emocionales son procesados por un mecanismo cognitivo que determina qué emoción sentir y, posteriormente, produce una reacción emocional que puede influir en la aparición del comportamiento. Los estímulos emocionales generalmente tienen prioridad en la percepción, se detectan más rápidamente y obtienen acceso a la conciencia consciente [99,100]. Los estímulos emocionales constituyen la base de la pirámide de inteligencia emocional que apunta a los niveles superiores de la misma. 3.2. Reconocimiento de emociones El siguiente nivel de la pirámide después de los estímulos emocionales es el reconocimiento de las emociones que se expresan simultáneamente a veces. La precisión es mayor cuando las emociones se expresan y reconocen. El reconocimiento de emociones incluye la capacidad de decodificar con precisión las expresiones de los sentimientos de los demás, generalmente transmitidas a través de canales no verbales (es decir, la cara, el cuerpo y la voz). Esta capacidad está vinculada positivamente a la capacidad e interacción social, ya que el comportamiento no verbal es una fuente confiable de información sobre los estados emocionales de los demás [101]. Elfenbein y Ambady comentaron que el reconocimiento de las emociones es el "componente validado de manera más confiable de la inteligencia emocional" vinculado a una variedad de resultados organizacionales positivos [102]. La capacidad de expresar y reconocer emociones en otros es una parte importante de la interacción humana diaria y las relaciones interpersonales, ya que es una representación de un componente crítico de las capacidades sociocognitivas humanas [103] 3.3. Conciencia de sí mismo Sócrates menciona en su principio guía, "conócete a ti mismo". Aristóteles también mencionó que "conocerse a sí mismo es el comienzo de toda sabiduría". Estos dos antiguos aforismos griegos abarcan el concepto de autoconciencia, una capacidad cognitiva, que es el siguiente paso en nuestra pirámide después de haber conquistado los dos anteriores. La autoconciencia es tener una percepción clara de su personalidad, incluidas sus fortalezas, debilidades, pensamientos, creencias, motivos y sentimientos [104]. A medida que desarrollas conciencia de ti mismo, puedes cambiar tus pensamientos, lo que, a su vez, te permite cambiar tus emociones y eventualmente cambiar tus acciones. Crisp y Turner [105] describieron la autoconciencia como una situación psicológica en la que las personas conocen sus rasgos, sentimientos y comportamientos. Alternativamente, se puede definir como la realización de uno mismo como una entidad individual. Desarrollar la autoconciencia es el primer paso para desarrollar su IE. La falta de autoconciencia en términos de entendernos a nosotros mismos y tener un sentido de nosotros mismos que tiene raíces en nuestros propios valores impide nuestra capacidad de autogestión y es difícil, si no imposible, saber y responder a los sentimientos de los demás. [61]. Daniel Goleman [106,107] reconoció la autoconciencia como conciencia emocional, autoestima precisa y confianza en sí mismo. Conocerte a ti mismo significa tener la capacidad de comprender tus sentimientos, realizar una autoevaluación precisa de tus propias fortalezas y debilidades y mostrar confianza en ti mismo. Según Goleman, la autoconciencia debe estar por delante de la conciencia social, la autogestión y la gestión de las relaciones, que son factores importantes de la IE 3.4. Autogestión Una vez que haya aclarado sus emociones y la forma en que pueden afectar las situaciones y otras personas, está listo para pasar al área de EQ de autogestión. El autocontrol te permite controlar tus reacciones para que no te guíen por conductas y sentimientos impulsivos. Con la autogestión, se vuelve más flexible, más extrovertido y receptivo, y al mismo tiempo menos crítico en las situaciones y menos reaccionario a las actitudes de las personas. Además, sabes más sobre qué hacer. Cuando haya reconocido sus sentimientos y los haya aceptado, entonces podrá manejarlos mucho mejor. Cuanto más aprenda sobre cómo manejar sus emociones, mayor será su capacidad para articularlas de manera productiva cuando sea necesario [108]. Esto no significa que deba aplastar sus emociones negativas, pero si se da cuenta de ellas, puede modificar su comportamiento y hacer pequeños o grandes cambios en la forma en que reacciona y administrar sus sentimientos, incluso si esta última es negativa. El segundo cuadrante de autocuidado de inteligencia emocional (EQ) consta de nueve componentes clave: (1) autocontrol emocional; (2) integridad; (3) innovación y creatividad; (4) iniciativa y perjuicio a la acción; (5) resiliencia; (6) guía de logros; (7) manejo del estrés; (8) optimismo realista y (9) intencionalidad [80,106,107,109]. 3.5. Conciencia social, empatía, discriminación de las emociones Ya que ha cultivado la capacidad de comprender y controlar sus propias emociones, está listo para pasar al siguiente paso de reconocer y comprender las emociones de las personas que lo rodean. La autogestión es un requisito previo para la conciencia social. Es una expansión de tu conciencia emocional. La conciencia social se refiere a la forma en que las personas manejan las relaciones y la conciencia de los sentimientos, necesidades y preocupaciones de los demás [110]. El grupo de Conciencia social contiene tres competencias: empatía, conciencia organizativa, orientación al servicio [107]. Tener conciencia social significa que comprende cómo reacciona ante diferentes situaciones sociales y que modifica efectivamente sus interacciones con otras personas para lograr los mejores resultados. La empatía es el componente de EQ más importante y esencial de la conciencia social y está directamente relacionado con la autoconciencia. Es la capacidad de ponerse en el lugar de otro (o "zapatos"), entenderlo como persona, sentirlo y tener en cuenta esta perspectiva relacionada con esta persona o con cualquier persona a la vez. Con la empatía, podemos entender los sentimientos y pensamientos de los demás desde su propia perspectiva y tener un papel activo en sus preocupaciones [111]. El resultado neto de la conciencia social es el desarrollo continuo de habilidades sociales y un proceso de mejora continua personal [107,112,113]. La discriminación de las emociones pertenece a ese nivel de la pirámide porque es una habilidad más bien intelectual que otorga a las personas la capacidad de discriminar con precisión entre diferentes emociones y etiquetarlas adecuadamente. La última en relación con las otras funciones cognitivas contribuye a guiar el pensamiento y el comportamiento [77]. 3.6. Habilidades sociales - Experiencia Después de haber desarrollado la conciencia social, el siguiente nivel en la pirámide de inteligencia emocional que ayuda a elevar nuestro EQ es el de las habilidades sociales. En inteligencia emocional, el término habilidades sociales se refiere a las habilidades necesarias para manejar e influenciar las emociones de otras personas de manera efectiva para manejar las interacciones con éxito. Estas habilidades van desde poder sintonizar con los sentimientos de otra persona y comprender cómo se sienten y piensan sobre las cosas, hasta ser un gran colaborador y jugador de equipo, hasta la experiencia en las emociones de los demás y en las negociaciones. Se trata de la capacidad de obtener lo mejor de los demás, inspirarlos e influir en ellos, comunicarse y establecer vínculos con ellos, y ayudarlos a cambiar, crecer, desarrollarse y resolver conflictos [114,115,116]. Las habilidades sociales bajo la rama de la inteligencia emocional pueden incluir Influencia, Liderazgo, Desarrollo de otros, Comunicación, Catalizador de cambios, Gestión de conflictos, Creación de vínculos, Trabajo en equipo y Colaboración [61]. La experiencia en emociones podría caracterizarse como la capacidad de aumentar la sensibilidad a los parámetros emocionales y la capacidad no solo para determinar con precisión la relevancia de la dinámica emocional para la negociación, sino también para exponer estratégicamente las emociones del individuo y responder a las emociones derivadas de otros [ 117] 3.7. Auto-actualización — Universalidad de las emociones Tan pronto como se han alcanzado los seis niveles, el individuo ha alcanzado la cima de la jerarquía de necesidades de Maslow; Auto-actualización. Cada persona es capaz y debe tener la voluntad de avanzar hasta el nivel de auto-actualización. La autorrealización, según Maslow [118,119,120], es la realización del potencial personal, la realización personal, el desarrollo personal y la experiencia máxima. Es importante tener en cuenta que la autorrealización es un proceso continuo de devenir, en lugar de un estado perfecto al que uno llega, como un "feliz para siempre" [121]. Carl Rogers [122,123] también creó una teoría que incluía un "potencial de crecimiento" cuyo propósito era incorporar de la misma manera el "yo real" y el "yo ideal", cultivando así la apariencia de la "persona en pleno funcionamiento". La autorrealización es una de las habilidades más importantes de la IE. Es una medida de su percepción de que tiene un compromiso personal sustancial con la vida y que está ofreciendo los regalos a su mundo que son más importantes para usted. Reuven Bar-On [124] ilustra la estrecha relación entre la inteligencia emocional y la autorrealización. Su investigación lo llevó a concluir que "usted puede actualizar su capacidad potencial para el crecimiento personal solo después de que sea social y emocionalmente efectivo para satisfacer sus necesidades y tratar la vida en general". Los auto-actualizadores sienten empatía y parentesco hacia la humanidad en general y, por lo tanto, cultivan la universalidad de las emociones, de modo que aquellos que tienen inteligencia emocional en una cultura probablemente también tengan inteligencia emocional en otra cultura y tengan la capacidad de comprender la diferencia de Las emociones y sus significados a pesar del hecho de que a veces las emociones son culturalmente dependientes [125,126] Maslow también propuso que las personas que han alcanzado la autorrealización a veces experimentarán un estado al que se refiere como "trascendencia". En el nivel de la Trascendencia, uno ayuda a los demás a auto-actualizarse, encontrar la realización personal y realizar su potencial [127,128]. El cociente emocional es fuerte y aquellos que han alcanzado ese nivel intentan ayudar a otras personas a entender y manejar sus propias emociones y las de los demás. La trascendencia se refiere a niveles mucho más altos y más amplios u holísticos de la conciencia humana, al comportarse y asociarse, como fines y no como medios, para nosotros mismos, para otros importantes, para los humanos en general, para otras especies, para la naturaleza y para el mundo [129]. La trascendencia está fuertemente correlacionada con la autoestima, el bienestar emocional y la empatía global. La autotrascendencia es la experiencia de verte a ti mismo y al mundo de una manera que no está impedida por los límites de la identidad del ego. Implica un mayor sentido de significado y relevancia para los demás y para el mundo [130,131]. En su percepción de la trascendencia, Platón afirmó la existencia de la bondad absoluta que caracterizó como algo que no se puede describir y que solo se conoce a través de la intuición. Sus ideas son objetos divinos que son trascendentes del mundo. Platón también habla de los dioses, de Dios, del cosmos, del alma humana y de lo que es real en las cosas materiales como trascendental [132]. La autotrascendencia se puede expresar de diversas maneras, comportamientos y perspectivas, como el intercambio de sabiduría y emociones con otros, la integración de los cambios físicos / naturales del envejecimiento, la aceptación de la muerte como parte de la vida, el interés en ayudar a los demás y aprender sobre ellos. el mundo, la capacidad de dejar atrás sus pérdidas y el descubrimiento de un significado espiritual en la vida [133]. 3.9. Unidad emocional La unidad emocional es el nivel final en nuestra pirámide de inteligencia emocional. Es una dinámica orientada de manera positiva e intencional, en el sentido de que apunta a alcanzar y mantener un dominio de las emociones, lo que informa al sujeto que él o ella está controlando la situación o el entorno en una forma aceptada. Este nivel alcanzado de unidad emocional en el sujeto puede interpretarse como un resultado de la inteligencia emocional [134]. La unidad emocional es una armonía interna. En la unidad emocional uno siente una alegría intensa, paz, prosperidad y una conciencia de la verdad última y la unidad de todas las cosas. En un mundo simbiótico, lo que haces por ti mismo, en última instancia, lo haces por otro. Todo comienza con nuestro amor por nosotros mismos, para que luego podamos canalizar este importante sentimiento a todo lo que existe a nuestro alrededor [135]. No solo en los seres humanos, sino también en animales, plantas, océanos, rocas, etc. Todo lo que se necesita es ver la chispa de la vida y el milagro en todo y ser más optimista. El punto es que de alguna manera, todos estamos interconectados, y mientras más profundizamos en nuestro corazón y lo seguimos, menos probable será que hagamos cosas que puedan dañar a otros o al planeta en general [136]. Los demás no están separados de nosotros. La unidad emocional emana humildad y empatía que conlleva las imperfecciones del otro. Platón en Parménides también habla sobre unidad [137], Ser y Uno. Como escribe Parménides: “El ser no es generado e indestructible, completo, de una sola clase, inquebrantable y completo. Ni fue, ni será, ya que ahora es, todos juntos, uno, continuo ... "[138,139 Ir: 4. Procesos cognitivos y metacognitivos en la pirámide de inteligencia emocional La cognición abarca procesos como la atención, la memoria, la evaluación, el lenguaje de resolución de problemas y la percepción [140,141]. Los procesos cognitivos utilizan el conocimiento existente y generan nuevos conocimientos. La metacognición se define como la capacidad de monitorear y reflexionar sobre el rendimiento y las capacidades propias [142,143]. Es la capacidad de los individuos para conocer sus propias funciones cognitivas para monitorear y controlar su proceso de aprendizaje [144,145]. La idea de la metacognición se basa en la distinción entre dos tipos de cogniciones: primaria y secundaria [146]. La metacognición incluye una variedad de elementos y habilidades tales como Metamemoria, Autoconciencia, Autorregulación y Autocontrol [144,147] La metacognición en la inteligencia emocional significa que un individuo percibe sus habilidades emocionales [148,149]. Sus procesos involucran estrategias emocionales y cognitivas tales como conciencia, monitoreo y autorregulación [150]. Además de la emoción primaria, una persona puede experimentar pensamientos directos que acompañan a esta emoción, ya que las personas pueden tener funciones cognitivas adicionales que controlan una situación emocional determinada [151], pueden evaluar la relación entre la emoción y el juicio [152], y pueden intentar para manejar su reacción emocional [153] para mejorar su propia personalidad y eso los motivará a ayudar a otras personas para lograr mejores interacciones interpersonales. La aplicación del metaconocimiento en contextos socioemocionales debe brindar la oportunidad de aprender a corregir los errores emocionales y promover la posibilidad futura de una respuesta adecuada a la situación mientras se mantiene y cultiva la relación [154]. En la pirámide de la Inteligencia Emocional, para pasar de una capa a otra, se producen procesos cognitivos y metacognitivos (Figura 2). Un archivo externo que contiene una imagen, ilustración, etc. El nombre del objeto es behavsci-08-00045g002.jpg Figura 2 Los procesos cognitivos y metacognitivos para pasar de una capa a otra. Ir: 5. Discusión y Conclusiones. La inteligencia emocional es un concepto muy importante que se ha vuelto a destacar en las últimas décadas y ha sido objeto de serias discusiones y estudios por parte de muchos expertos. La importancia de la inteligencia general no se subestima ni cambia, y esto se ha demostrado a través de muchas encuestas y estudios. Por otro lado, sin embargo, también debemos dar a la inteligencia emocional el lugar que merece. El cultivo de la inteligencia emocional puede contribuir y proporcionar muchos beneficios positivos para la vida de las personas de acuerdo con los estudios, encuestas y con lo que ya se ha mencionado. Cuando se trata de la felicidad y el éxito en la vida, la inteligencia emocional (EQ) importa tanto como la capacidad intelectual (IQ) [60]. Además, debe observarse que a pesar de las diversas discusiones sobre la inteligencia emocional, los estudios han demostrado que las capacidades emocionales que componen la inteligencia emocional son muy importantes para el funcionamiento personal y social de los humanos [83]. Una red central de regiones cerebrales como la amígdala y la corteza prefrontal ventromedial es la clave para una gama de capacidades emocionales y desempeña un papel crucial para las lesiones humanas [155]. Los componentes específicos de la Inteligencia Emocional (Comprender las emociones y Manejar las emociones) están directamente relacionados con la microarquitectura estructural de las principales vías axiales [156]. Con la inteligencia emocional usted reconoce, acepta y controla sus emociones y reacciones emocionales, así como las de otras personas. Aprendes sobre ti mismo y pasas a la comprensión del yo de otras personas. Aprendes a coexistir mejor, lo cual es muy importante ya que no estamos solos en este mundo y porque cuando queremos avanzar, y la sociedad en su conjunto, debe haber cooperación y armonía. Con la inteligencia emocional, aprendes a insistir, a controlar tus impulsos, a sobrevivir a pesar de las adversidades y dificultades, a esperar ya tener empatía. La Inteligencia Emocional le proporciona un mejor mundo interior para hacer frente al mundo exterior según el Rasgo EI [157]. Implica e involucra funciones cognitivas superiores como atención, memoria, regulación, razonamiento, conciencia, monitoreo y toma de decisiones. Los resultados muestran que el estado de ánimo negativo y el miedo anticipado son dos factores de la relación entre la IE característica y la toma de riesgos en los procesos de toma de decisiones entre los adultos [158]. La investigación también ha demostrado esta correlación positiva entre la inteligencia emocional y los procesos cognitivos, lo que demuestra el importante papel que juega la inteligencia emocional con la emoción y la cognición, lo que fortalece a los individuos y su personalidad y beneficia a toda la sociedad [159,160,161,162,163,164]. A medida que nos elevamos a través de los niveles de la pirámide de inteligencia emocional que hemos presentado, nos acercamos más a su desarrollo en la mayor medida posible, a la universalidad de las emociones, a la unidad emocional. El ser humano es bueno al tratar de alcanzar el último nivel de la pirámide porque en cada nivel cultiva importantes habilidades emocionales, cognitivas y metacognitivas que son recursos importantes para el éxito en la vida personal, la vida profesional, las relaciones interpersonales y la vida. en general. La inteligencia emocional es una habilidad que puede aprenderse y desarrollarse [165,166]. El modelo de inteligencia emocional ha sido creado con una mejor clasificación distinta. Es un modelo de evaluación e intervención más estructurado con niveles jerárquicos para indicar cada nivel de inteligencia emocional en el que todos se encuentran y con los procedimientos operativos para contribuir al fortalecimiento de ese nivel y el desarrollo progresivo del individuo a los siguientes niveles de inteligencia emocional. Es una metodología para el posterior desarrollo y evolución del individuo. Este modelo puede tener aplicaciones prácticas como herramienta de evaluación, evaluación y capacitación en cualquier aspecto de la vida, como las relaciones interpersonales, el trabajo, la salud, la educación especial, la educación general y el éxito académico. Los investigadores afirman que una mente emocional es importante para una buena vida tanto como una mente inteligente y, en ciertos casos, es más importante [167]. El objetivo final debería ser desarrollar la Inteligencia Emocional, investigar más sobre los beneficios de una capacidad tan importante y las correlaciones entre el modelo de Inteligencia Emocional en capas y otras variables. En este documento, presentamos la pirámide de la Inteligencia Emocional como un intento de crear un nuevo modelo de capas basado en habilidades emocionales, cognitivas y metacognitivas. En esencia, cada nivel superior de la pirámide es una mejora hacia el crecimiento personal y un estado superior de autorregulación, autoorganización, conciencia, conciencia, atención y motivación. Ir: Contribuciones de autor A.S.D. y C.P. Contribuyó igualmente en la concepción, desarrollo, redacción, edición y análisis de este manuscrito. Los autores aprobaron el borrador final del manuscrito. Ir: Fondos Esta investigación no recibió financiación externa. Ir: Conflictos de interés Los autores declaran no tener conflicto de intereses. Ir: Referencias