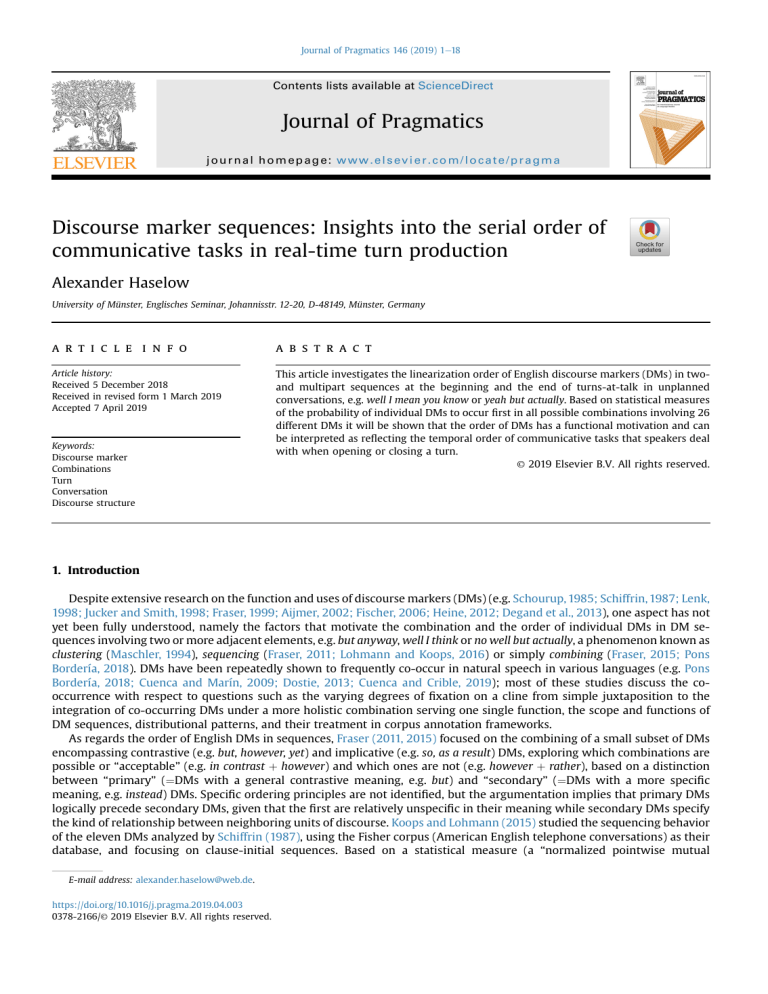

Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Pragmatics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/pragma Discourse marker sequences: Insights into the serial order of communicative tasks in real-time turn production Alexander Haselow University of Münster, Englisches Seminar, Johannisstr. 12-20, D-48149, Münster, Germany a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Received 5 December 2018 Received in revised form 1 March 2019 Accepted 7 April 2019 This article investigates the linearization order of English discourse markers (DMs) in twoand multipart sequences at the beginning and the end of turns-at-talk in unplanned conversations, e.g. well I mean you know or yeah but actually. Based on statistical measures of the probability of individual DMs to occur first in all possible combinations involving 26 different DMs it will be shown that the order of DMs has a functional motivation and can be interpreted as reflecting the temporal order of communicative tasks that speakers deal with when opening or closing a turn. © 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Discourse marker Combinations Turn Conversation Discourse structure 1. Introduction Despite extensive research on the function and uses of discourse markers (DMs) (e.g. Schourup, 1985; Schiffrin, 1987; Lenk, 1998; Jucker and Smith, 1998; Fraser, 1999; Aijmer, 2002; Fischer, 2006; Heine, 2012; Degand et al., 2013), one aspect has not yet been fully understood, namely the factors that motivate the combination and the order of individual DMs in DM sequences involving two or more adjacent elements, e.g. but anyway, well I think or no well but actually, a phenomenon known as clustering (Maschler, 1994), sequencing (Fraser, 2011; Lohmann and Koops, 2016) or simply combining (Fraser, 2015; Pons Bordería, 2018). DMs have been repeatedly shown to frequently co-occur in natural speech in various languages (e.g. Pons Bordería, 2018; Cuenca and Marín, 2009; Dostie, 2013; Cuenca and Crible, 2019); most of these studies discuss the cooccurrence with respect to questions such as the varying degrees of fixation on a cline from simple juxtaposition to the integration of co-occurring DMs under a more holistic combination serving one single function, the scope and functions of DM sequences, distributional patterns, and their treatment in corpus annotation frameworks. As regards the order of English DMs in sequences, Fraser (2011, 2015) focused on the combining of a small subset of DMs encompassing contrastive (e.g. but, however, yet) and implicative (e.g. so, as a result) DMs, exploring which combinations are possible or “acceptable” (e.g. in contrast þ however) and which ones are not (e.g. however þ rather), based on a distinction between “primary” (¼DMs with a general contrastive meaning, e.g. but) and “secondary” (¼DMs with a more specific meaning, e.g. instead) DMs. Specific ordering principles are not identified, but the argumentation implies that primary DMs logically precede secondary DMs, given that the first are relatively unspecific in their meaning while secondary DMs specify the kind of relationship between neighboring units of discourse. Koops and Lohmann (2015) studied the sequencing behavior of the eleven DMs analyzed by Schiffrin (1987), using the Fisher corpus (American English telephone conversations) as their database, and focusing on clause-initial sequences. Based on a statistical measure (a “normalized pointwise mutual E-mail address: [email protected]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2019.04.003 0378-2166/© 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 2 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 information score”) of what they call the “association strength” of each two-part DM combination the authors propose an “optimal sequencing hierarchy for DM sequences” in their set, which is as follows: oh > well> and > so > or > but > because > then > you know > now > I mean (also Lohmann and Koops, 2016). Crible (2017) studied the combination or clustering of different types of DMs with other markers of (dis)fluency, so-called “fluencemes” (e.g. filled and unfilled pauses, repetitions, or truncations), across different registers in a contrastive corpus-based study of spoken English and French. Her study provided insights into the co-occurrence, position and distribution of DMs in combinations with other kinds of fluencemes. Crible finds that the most frequent patterns of combination are various configurations of DMs with filled and unfilled pauses, such as ‘DM þ pause’, of which more than ten specific configurations are attested (e.g. ‘filled pause þ DM’ or ‘unfilled pause þ DM þ filled pause’). Recently, Cuenca and Crible (2019) provided a qualitative analysis of formal and functional features of DM sequences in conversational English, discussing the different degrees of integration of DMs in such sequences, which range from free juxtaposition to fixed composition and several ambiguous and in-between cases. This paper takes a different perspective, looking at DM sequences at the beginning and the end of conversational turns from a more general cognitive and theoretical-linguistic point of view, based on conversational data deriving from spoken English. As regards cognitive aspects, the linear order within DM sequences might reflect the order of communicative tasks to which speakers are cognitively oriented at turn-beginnings and -endings, an idea which I will refer to as the DM Sequencing Hypothesis. This assumption rests upon the fact that DMs express a broad range of procedural meanings (Blakemore, 2002) that provide processing cues for utterance interpretation. With respect to theory building in linguistics, DM sequences provide important empirical evidence relevant for grammatical modeling, given that regularities in the linear order of different functional types of DMs are indicative of functionalegrammatical linearization principles involving linguistic forms that are used as “extra-clausal constituents” (Dik, 1997) outside clause-internal dependency relations. The aim of this article is to offer an empirical investigation of the sequencing behavior of a larger set of turn-initial and -final DMs in spoken English in order to identify general patterns that determine the linear order of DMs, to examine the possible functional motivations behind the linearization principles observed, and to derive general principles that have the potential to converge into a processing-based communicative grammar of structural units produced in real time. The structure is as follows: Section 2 provides a brief description of the approach to DMs and DM sequences taken in this study, Section 3 is devoted to a discussion of turn-beginnings and -endings as communicatively sensitive moments in turn production at which speakers need to deal with a broad range of communicative tasks. The database and method are presented in Section 4, empirical data are provided in Sections 5 and 6 and discussed in Section 7. The article ends with a conclusion and an outlook on further research (Section 8). 2. Discourse markers and discourse marker sequences 2.1. Discourse markers In this study a DM is defined as a lexical expression with particular formal and functional features, which were systematically applied as operational criteria to data deriving from natural speech. Formally, DMs are characterized by syntactic optionality (they can be omitted without affecting grammaticality because they are outside morphosyntactic and semantic dependency relationships holding between clausal constituents), lack of semantic content, and non-truth conditionality (Schourup, 1999). DMs convey procedural rather than lexicaleconceptual meaning (Blakemore, 2002), providing a processing cue on how the unit they accompany is to be understood or interpreted within a given communicative context. Moreover, they exhibit a high degree of conventionalization or grammaticalization (see Crible, 2017). Functionally, DMs situate an utterance within the communicative context in which it is produced in a wider sense, which is congruent with Schiffrin's (1987) description of DMs on five different “planes of talk” (information state, participation framework, ideational structure, action structure, and exchange structure), and Redeker's (2006) definition of discourse operators as expressions that relate a discourse unit to the immediate “discourse context”, whose nature is not restricted to the linguistic context, but also pertaining to relations between nonlinguistic, nonpropositional aspects of discourse (also Diewald, 2013). For instance, DMs may establish relations between action sequences across larger stretches of discourse (see Crible and Cuenca, 2017: 153), as illustrated in (1). (1) 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 B: C: B: C: B: Caroline are you coming to the pub tonight? no I'm not coming to the pub tonight. [I'm going to Birkbeck.] [why not? ] you SWOT. <laugh> oh yes I know. (.) I have to swot. I'm not clever like you lot. (..) anyway listen so when are we going together then to do this revision. [ICE-GB S1A-090] A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 3 As a DM, anyway expresses a shift away from the prior discourse sequence consisting of a teasing action and initiates the beginning of a new interactional sequence, for which B then requests the addressee's attention (listen). The DM so that follows establishes an inferential relationship between prior and upcoming discourse (if C has to swot he will not have time to get together with B and “do the revision”). Such examples show how DMs establish structures in different domains of spoken interaction, e.g. between conversational actions, episodes, or between explicit and implied meanings (see also Hansen, 2006; Gonz alez, 2005; Crible, 2017). As cues for discourse processing, DMs contribute to the development of a coherent mental model of ongoing interaction and discourse by integrating single units of discourse into a unified whole. Given that ‘discourse’, loosely defined as what is said (or written) in a particular communicative context, involves (i) different speakers who need to structure their interaction, (ii) (spoken) text and thus textual relations that require overall coherence in order for emergent discourse to be perceivable as an organized whole, as well as (iii) different minds involved in the processing of emergent discourse that coordinate the processing of all aspects related to interaction, we can distinguish three basic functional domains that form the communicative “matrix” of discourse and within which DMs operate in order to establish structural relations: (i) INTERACTION, (ii) DISCOURSE STRUCTURE, and (iii) COGNITION, as shown in Table 1.1 Note that a single DM may serve a broader set of functions in different contexts (e.g. Fischer, 2000; Crible, 2017; Crible and Cuenca, 2017), but mostly DMs can be related to core domains in which they prototypically operate. Table 1 Functional domains of discourse markers. Domain General Function Examples (i) INTERACTION listen, …isn't it? (ii) DISCOURSE STRUCTURE (iii) COGNITION organizing turn-taking and interaction (e.g. setting up the conditions for successful uptake of an upcoming message) indicating the type of (local, global) relationship between discourse units or between a discourse unit and implied meanings or inferences providing a cue for utterance-interpretation and, anyway, but, so I think, you know The domain INTERACTION (i) includes all functions related to the management of speakereaddressee interaction and the structuration of the periodic change of speaker roles in interaction. DISCOURSE STRUCTURE (ii) refers to the relationship between discourse units, which encompasses ideational (semantic) relations (e.g. contrast, concession), rhetorical relations (meta-comments on the nature of an upcoming unit, e.g. an inference or a reformulation), and topical aspects (e.g. topic shift, lez, 2005; Redeker, 2006; Crible, 2017). The third domain COGNITION (iii) encompasses DM topic resumption) (see also Gonza functions relating to the alignment of the co-participant's cognitive states and thus serves structuration in terms of jointly constructed mental representations of emergent discourse. For instance, DMs may refer to (presumed) shared background knowledge, inferential abilities, or provide a cue as to how a message is to be interpreted and integrated into the common ground (the set of shared knowledge, beliefs and background assumptions, Stalnaker, 2002), e.g. as expressing an opinion rather than a fact (I think). The DM you know, for instance, invites the addressee to recognize the implications and “sequential relevance” of an assertion or an expression (Schourup, 1985: 105), as illustrated in (2). (2) 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 B: A: B: A: B: A: so uhm (..) so (.) are you still on call (.) at work you know¿ (.) no. no. what do you mean on call. you know uhm tran- uhm transplant. transplant call. yes we are […] [ICE-GB S1A-099] As a DM, you know in line 44 indicates that the question implies more than a mere reference to A's current task at work, based on the fact that speaker and addressee share relevant knowledge, thus inviting B to specify or elaborate on his current work. This also holds for the use of you know in line 48, which accompanies a reference that lacks expressive precision (transplant) and marks it as being linked to what is already shared and thus related to additional implications (see Jucker and Smith, 1998: 191e197). Based on these considerations, the term ‘discourse marker’ as it is used here encompasses a broader range of expressions often referred to under specific categorical labels in the literature, such as interjections (e.g. oh), linking adverbials/final particles (e.g. final then or though), general extenders (e.g. and stuff), parentheticals/comment clauses (e.g. I think), or tag 1 A similar distinction is made by Maschler (2009: 117), who categorizes DMs into three classes: textual, interpersonal, and cognitive. 4 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 questions (e.g. isn't it?), all of which fulfil the formal criteria given above and serve the integration of a message into the communicative context in which it is produced. 2.2. Discourse marker sequences ‘DM sequences’ are defined as a combination of two or more non-identical, immediately adjacent DMs (thus excluding discontinuous co-occurrences of two DMs), provided that each DM is also used outside such sequences as an independent form. Sequences of identical markers may functionally differ from the single use of the DM (e.g. oh oh vs. oh or well well vs. well), and thus be more likely to trigger holistic processing under a different, non-compositional idiosyncratic meaning. The problem of compositionality also refers to sequences of DMs that are not identical, given that some DMs occur frequently together and have developed some degree of idiomaticity as a result of their strong mutual association (Cuenca and Marín, 2009; Cuenca and Crible, 2019). For instance, Schourup (2001: 1031) finds that oh well has become “conventionalized” to “indicate resignation”. The difference between more or less idiomatic and thus non-compositional uses of DM sequences and free, serial combinations, is a gradual one and difficult to determine in many cases. Since all of the DMs analyzed in the present study are regularly in use as autonomous lexemes and since all of the combinations allow for compositional readings they will all be treated as representing free, serial configurations. Several proposals have been made as regards the motivation behind DM sequencing, which can be referred to as (i) floorholding, (ii) functional specification, and (iii) functional complementation. The first proposal assumes that DMs often co-occur for no specific function as a device to hold the floor and bridge a gap during a cognitive planning pause, the DMs having little function themselves (Aijmer, 2004: 186). Under this view, sequences such as okay so or well you know would have to be analyzed as largely redundant and merely serving as a communicative strategy to bridge disfluencies during real-time speech processing. (ii) assumes that DMs occur in sequences because one DM specifies the function of the one with which it co-occurs. Examples are usually provided for DMs expressing a contrastive relationship (Oates, 2000; Fraser, 2015): sequences such as but nevertheless are explained as being motivated by combining the vague meaning of but, which indicates some kind of contrast in a general way, with the more specific meaning of nevertheless, which indicates a concessive relation. Under the third proposal (iii) it is assumed that DMs co-occur because the speaker combines different communicative functions (e.g. Cuenca and Marín, 2009), which would account for the large number of cases where the DMs involved clearly have separate functional values as they indicate relations on different planes of talk, e.g. the textual (e.g. but, so) and the interpersonal plane (e.g. you know, actually). Pons Bordería (2018), using a classification of DMs based on textual, interpersonal, and modal functions for the study of DM combinations in spoken Spanish, observed that DMs with textual functions are preferred in such combinations. 3. Discourse markers at turn-beginnings and -endings: functional aspects In the present study the focus will be on DM sequences at turn boundaries, i.e. at the beginning and end of turns, which means that other positions and factors motivating the use of DM sequences are not explicitly dealt with here. This choice is motivated by the fact that at turn boundaries speakers need to deal with a large set of generic communicative tasks, given that these points represent periodically arising transitional points as regards speaker roles, ideas (expressed by different speakers), and actions, and are thus crucial for the development of discourse. Hence, the need for maintaining order at all levels of the communicative system is very high at such points. An example for the preferred uses of DMs and DM sequences in such contexts is given in (3). (3) 186 187 188 A: 189 190 191 192 193 A: B: A: B: B: yeah. well I was only there for a week so it wasn't as if I was going to get anything. no but actually you weren't supposed- you were advised not to drink water in Leningrad because they they have this special bug (.) that's only found there and in Wolverhampton. it's amoeba isn't it? amoebic. amoebic dysentery yeah. but it did happen. Warren Martin got it from our group […] [ICE-GB S1A-014] At turn-beginnings, both speakers deal with different tasks that can be assigned to the three functional domains given in Table 1, such as acknowledging prior talk (yeah), which refers to structuration in the domain of INTERACTION, or various discourse-structuring tasks such as projecting a shift away from what the prior speaker said (no, see also Lee-Goldman, 2011) toward a new focus (but in line 188) that is potentially unexpected for the addressee (actually), or a contrast to what has just been said (but in line 192). At the end of a turn, a different set of communicative tasks becomes relevant, such as eliciting addressee response (isn't it?) or retrospectively marking what has just been said as coinciding with a prior speaker's assertion (yeah), both of which refer to interaction management. The strong tendency for DM sequences to occur at turn-beginnings and -endings has also been observed in other studies (Cuenca and Marín, 2009; Pons Bordería, 2018). A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 5 A ‘turn’ is defined here in conversation-analytic terms as a stretch of speech occupied by a single speaker who is recognizably claiming the conversational floor. This definition excludes two cases: (i) in cases of overlaps and interruptions, a turn is only analyzed as such if at least one third of it (measured in words) is produced “in the clear”; (ii) excluded are utterances that serve merely backchanneling functions (McCarthy, 2003; Rühlemann, 2017), i.e. that are produced during or after another speaker's turn and not followed by more talk (e.g. mhm, yeah or that's right), since these are “not construed as full turns, but rather pass up the opportunity to take a turn” (Levinson and Torreira, 2015: 8). They serve a supportive function as “go-on signals” or displays of attention, involvement, comprehension and encouragement, but not as recognizable attempts to adopt the speaker role. However, if a backchannel item is followed by more talk it is included in the present study as part of a turn, as illustrated in (4), where the speaker clearly contributes more content to emergent discourse after an initial backchanneling device (yeah). (4) 39 40 A: B: you could commission prints of yourself. yeah but I can't afford that kind of thing. [ICE-GB S1A-015] In (4), yeah is used as brief reception token expressing a “pro-forma” agreement (Schegloff, 2007) and preparing the ground for upcoming talk after speaker transition. Table 2 Provides an overview of the generic tasks that speakers are faced with at turn-beginnings, which correspond to the three domains discussed above and many of which have been discussed in the literature (e.g. Auer, 1996; Deppermann, 2013; Heritage, 2013; Haselow, 2017: Ch. 4). Table 2 Communicative tasks relevant at turn-beginnings. Domain Communicative tasks INTERACTION DISCOURSE STRUCTURE COGNITION getting/claiming the attention of the addressee dealing with turn-taking issues; indicating entitlement to take the turn responding to prior talk (e.g. signaling uptake, understanding, acknowledgment) indicating the kind of relation to prior talk (ideational, rhetorical, topical) initiating a new conversational action providing interpretive cues for an upcoming message indicating how to integrate an upcoming message into the common ground At turn-beginnings, speakers mainly deal with linking upcoming talk back to prior talk, and with projections, i.e. with the task of pointing into the discursive future in terms of what will follow in upcoming talk and how this is to be processed or interpreted. The preliminary end of a turn is a second crucial moment in ongoing discourse production in so far as it allows speakers to deal with various communicative tasks before potential turn transition (see Table 3). Table 3 Communicative tasks relevant at turn-endings. Domain Communicative tasks INTERACTION DISCOURSE STRUCTURE COGNITION facilitating addressee-response addressing different aspects of the relationship to the addressee (e.g. backchanneling) marking a transition-relevance place and thus legitimizing turn transition retrospective integration of a turn into ongoing discourse (indication of the kind of relation to prior talk) providing a last interpretive cue before potential turn transition interpretive fine-tuning of a message just produced (e.g. in terms of epistemic value, illocutionary force, canceling possible implicatures) The beginning and end of a turn are thus two crucial moments in the linear production of a unit of talk as they “shape the organization of turns-at-talk” (Schegloff, 1996: 54) in a recurrent way. They correlate with DM use since these represent a routinized communicative resource by which speakers deal with the dense network of recurrent generic tasks. As regards DM sequences it appears plausible that in such contexts these tasks follow a particular temporalelogical order, which would explain possible ordering principles underlying the use of DMs in sequences. This assumption derives from the fact that speakers are forced into the temporal emergence of linear structure, i.e. they can deal with only one single task at a time, which requires sequential ordering (which is, of course, highly automated and thus intuitive) that must be based on directionality in the sense that some tasks need to be addressed earlier (basically those that are oriented backward in discourse) than others (e.g. those that are forward-oriented). 6 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 Based on these considerations, the motivation behind DM sequences and the ways in which DMs are ordered in such sequences can be formulated by way of the following hypothesis: Discourse Marker Sequencing Hypothesis The sequential order of discourse markers reflects the temporal logics of communicative tasks to be performed at a particular moment in turn production. This hypothesis forms the background of the empirical study on the linearization order of DMs in sequences presented here. 4. Database and method 4.1. Database The data related to DM sequences are based on the spoken section of the British component of the International Corpus of English (ICE-GB, sections S1AeS2B), which is based on 1,193 speakers who produced 637,682 words. The ICE-GB offers transcripts of spontaneous (unscripted) speech in private and public contexts (e.g. conversations, broadcast discussions, business transactions), and thus comparatively rich material for DM sequences, which are most frequent in unplanned realtime speech produced in interactive contexts. Each single occurrence of a DM sequence had to be inspected manually after a computerized search. Manual inspection was required for two reasons: (i) to separate all instances of DM sequencing occurring at turn-beginnings and -endings from all other contexts in which such sequences often occur and where they may serve other functions (e.g. within turns), and (ii) to eliminate all cases in which the computerized search delivered results that are clearly not interpretable as DM sequences, e.g. when then is used as a time adverb rather than as a DM in a sequence, when because is followed by of (e.g. well because of…) and thus clearly a preposition, or when you know is followed by a complement clause and thus not used as a DM, but as a matrix clause. 4.2. Method: transitional probabilities The relative position of an individual DM x in various possible turn-initial and -final sequences xy involving any other DM y from a set of DMs was measured on the basis of direct transitional probabilities (DTPs, Gregory et al., 1999; Kapatsinski, 2005) between x and all ys. DTP is a probabilistic measure developed for bigrams that rates the likelihood of a given word to be followed by another word, and thus of the association strength between two consecutive words. The measure was applied here to each individual, two-part DM combination in order to determine the likelihood of a given DM to be followed by other DMs. DTP is defined as the frequency of an individual DM sequence xy divided by the frequency of the first DM x in all turninitial or -final sequences (whether as first or as second element), as shown in (5). Thus, DTP as used here does not measure the overall probability of x to be followed by y in the corpus, but only the probability of x to be followed by y in sequences of DMs (bigrams) at the beginning or the end of turns. (5) DTP ¼ FrequenySequence xy FrequencyDM x in all sequences at turnbeginnings or endings For instance, well co-occurs with I think and is the first element in the combination well I think at the beginning of turns 49 times in the ICE-GB. Generally, well occurs 296 times as part of a combination with any of the 15 turn-initial DMs included in the present study (see section 5.1), either as a first or a second element. Thus, the DTP for the combination well I think is 49/296 ¼ .1655, i.e. the probability of well being the first element followed by I think at turn-beginnings is .1655. The reverse order, I think well, is attested only once among the 110 tokens with I think as the first element in all DM sequences, resulting in a DTP of .009. Thus, the order well I think is more likely than I think well, i.e. in this DM combination well has the tendency to precede I think. If we aggregate all bigram DTPs for a single DM in all possible two-part combinations including this DM, we arrive at a general DTP value for an individual DM that indicates its overall probability to be followed or preceded by other DMs. A high overall DTP would thus indicate a high probability for x to precede all ys in sequences, i.e. such DMs are more likely to occur first in DM sequences. All DTP values are distributed over a [0,1] interval, with values close to 1 indicating high probability. Note that in order to reach highest accuracy all DTPs are based on token frequencies rather than on normalized frequencies (especially since some sequences are very rare, and yet indicative of what speakers do). A particular sequence xy may be part of an even longer sequence xyz (e.g. well I think actually) or wxyz (e.g. yeah well I think you know), but in any case the direct transitional probabilities measured for x in all xy combinations would be indicative of x's probability (e.g. that of well) to precede or follow any other DM y. Thus, the DTPs for a single DM in two-part sequences lead to a general DTP value that indicates the probability of a DM x to be followed (or not) by any DM y from the list in Table 4 for sequences of any size. A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 7 5. The frequency of discourse markers at turn-beginnings and -endings 5.1. Turn-initial discourse markers Table 4 shows the DMs that were inspected for their use in sequences, indicating the token frequency at turn-beginnings and their overall token frequency in the corpus. All in all 16 DMs were included as these were the DMs that occurred frequently enough to be part of turn-initial DM sequences at least with some regularity in the ICE-GB and with occurrences that were frequent enough for significance tests. Table 4 Frequency of turn-initial DMs in the ICE-GB (spoken sections). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Form Frequency turn-initial Overall frequency yeah yes so oh well I mean no but I think OK because and anyway then actually you know 2,520 2,149 1,848 1,596 1,518 1,013 701 567 542 452 446 322 134 109 98 49 2,746 2,531 3,474 1,623 2,955 1,409 2,472 4,134 1,022 558 1,535 12,586 269 1,629 956 1,005 The low figures for some DMs such as and and but in Table 4 may be surprising, given their high overall frequency in speech. However, at turn-beginnings they tend to be less frequent than within turns, which suggests that they are more frequently used to link different turn-constructional units into a coherent turn rather than to initiate a new turn. An example for turn-initial uses of but in sequences is given in (6), where it is used as a device to reshift the focus of the conversation. The talk is a classroom conversation at UCL. B is a student asking the instructor A whether there is a possibility to attend a tutorial in the upcoming term. (6) 018 019 020 A: B: A: you know I think it's not going to be possible actually to to do that next term unfortunately. but I mean if I if I need some help could I still come? yeah but I don't think there'll be formal tutorials. [ICE-GB S1B-015] B uses but to indicate a move away from A's assertion that attenting a tutoral will not be possible, given that B is interested in getting to know whether he might ask for some help in general. After the production of but he adds a second DM (I mean), which indicates that he is about to specify his point. After weakly confirming B's request (yeah), A indicates a mild contrast to a possible implicature in B's turn, which is that the “help” requested might go beyond occasional, specific questions and thus require the formal setting of a tutorial, which cannot be offered. And is usually used to indicate that the upcoming turn continues a prior action or topic, as shown in (7), i.e. it serves as a functionally generalized device to signal continuation in discourse, e.g. the continuation of a story after a brief intervention by the co-participant. It is often combined with so, which indicates a conclusion or result. In (7), A tells B how she and her friend Leo each invented a language that the other one cannot fully understand. (7) 201 202 198 199 200 201 B: A: B: A: B: A: how do you know how to write him. uhm (.) well I've learnt it. from him. yeah. right. and uhm so I've I've written a few short texts in it like the Lord's prayer I've translated. [ICE-GB S1A-015] A second speaker may also use and to continue or add to a prior speaker's utterance, as in (8), where speaker A combines and with so, which in this case signals that the turn expresses an inference drawn from B's utterance that requires confirmation. 8 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 (8) 23 24 25 B: A: B: and it it faces south and it has big rooms and it's a nice house (.) and, and so the sun comes in. oh yes (..) yes mm. [ICE-GB S1A-031] The figures in Table 4 suggest that the most frequent turn-beginning devices are INTERACTION markers with a transitional function (yeah, yes, no, oh) and markers operating in the domain of DISCOURSE STRUCTURE, indicating a particular kind of progression in discourse, e.g. a continuation or a conclusion (and, so). 5.2. Turn-final discourse markers The forms available for use at the potential end of a turn as attested in the ICE-GB can be categorized into six formal categories: (i) Final particles (FPs) (Haselow, 2012, 2013; Hancil et al., 2015): actually, anyway, then, though (only in final position, where they serve functions that are clearly distinct from their uses in other positions); (ii) General Extenders (GEs) (Overstreet, 1999, 2014; Pichler and Levey, 2011): and stuff, and that, and everything, and so on, or whatever, or something, and all, and all…that sort of thing/…that nonsense/…sorts/…that stuff/…this/ …that); (iii) If-chunks (Brinton, 2008: 163e166): if you like, if I may, if I may say so, if you want, if you don't mind me saying, if you know what I mean; , 2014): I think, you know; (iv) Parentheticals (Dehe (v) Tag questions (Tottie and Hoffmann, 2006, 2009): based on the positive and negative forms of be, can, could, do, have, may, should, and would plus a personal pronoun (e.g. isn't it?, shouldn't he?); (vi) Strengtheners (Haselow, 2017: 183e184): yeah. Table 5 shows the frequency of turn-final DMs from the six categories in the spoken sections of the ICE-GB. Note that for FPs the frequency of all single forms is given since, in contrast to individual forms in all other categories, they are frequent enough to be statistically relevant. Table 5 Frequency of turn-final DMs in the ICE-GB (spoken sections). 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. Tags GEs then though anyway actually I think you know if-chunks yeah Frequency turn-final Overall frequency 405 302 191 162 135 144 95 53 35 23 447 316 1,629 319 269 956 1,022 1,005 35 2,746 An example for DM sequences at turn-endings is (9), where speaker C combines a GE with a tag question. (9) 40 41 42 C: B: well when it came when he came back from America just didn't seem as as though he was, (..) I mean he's got he's got a lot of problems at work and with the gypsies and everything hasn't he. yeah. [ICE-GB S1A-049] The GE and everything marks the turn as providing incomplete, potentially expandible information on the “problems at work”, where “with the gypsies” is only one example from a larger set. The tag question hasn't he serves as a device to elicit a response by the addressee, who is involved into ongoing talk by being invited to contribute. A further example is (10). (10) 174 175 176 A: B: A: Vicky's not awfully good on time. we should maybe just leave a message here saying head over. (.) she won't bother coming then though. [ICE-GB S1A 039] A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 9 Here, speaker A combines two FPs, then indicating that the prior message is inferentially related to B's utterance, though indicating that the content expressed in the turn goes against the implication of B's proposal, which is that leaving a note and thus sanctioning Vicky's behavior would change anything. 6. Discourse marker sequences at turn-beginnings and -endings: empirical findings 6.1. Discourse marker sequences at turn-beginnings Table 6 shows the token frequency of each DM combination (upper figures) and the DTPs (lower figures). The table reads as follows: the DMs in the left column are the starting point for combinations with DMs from the horizontal axis, i.e. they form the first DMs x in sequences xy involving DMs of type y from the horizontal axis with the frequencies and DTPs indicated. When the data are read from the top to the bottom, the figures indicate the use of each of the DMs in the uppermost row as a second DM y in a sequence xy. Note that the overall frequency of each DM in Table 6 is much lower than its overall frequency at turn-beginnings (see Table 4), given that all DMs also occur e often much more frequently e as single DMs in this position, and thus outside sequences. Since DTP considers only the frequency of a DM in sequences at turn-beginnings, we are able to level the considerable differences in overall frequency between the different DMs to some extent. This, in turn, accounts more realistically for the psychological effects of DM clustering: combinability and ordering principles should, in principle, be unrelated to the overall frequency of individual DMs in the corpus, but related to the degree to which particular DMs tend to co-occur with other DMs relative to their overall occurrence in combinations. The sums in the rightmost column are aggregated DTPs and thus indicate the probability of a DM x to be used in all xy P sequences as the first element (rightmost column: ‘ [1st]’), that is, to precede all other DMs. The sums in the bottom row P indicate the aggregated DTPs for x not being the first element in a DM sequence (bottom row: ‘ [s1st]’) in the data. The respective cells also show the ratio of occurrences in first (right column)/not first position (bottom row) and the overall occurrence of the respective DM in sequences at turn-beginnings. The data indicate that some DMs have a stronger mutual attraction than others as they enter into combinations more frequently. Some DMs appear to be less combination-friendly (e.g. you know, which co-occurred only with and) than others, and some are much more frequent as first elements (e.g. oh, well) than others (e.g. I think). Almost all two-part combinations show a bias toward a specific serial order as one order (e.g. xy) statistically always predominates over another (e.g. yx). For example, when well and actually are combined, well is only attested as the first element (11 tokens, DTP ¼ .0371), whereas the reverse order (actually well) is unattested. The same holds e.g. for the combination of but and I mean: but I mean is attested with 21 tokens (DTP ¼ .1372), whereas I mean but did not occur in the data. This suggests that there are strong preferences for some DMs to precede and for others to follow the DMs with which they are combined, an observation that is congruent with the findings by Lohmann and Koops (2016) for utterance-initial DMs in a corpus of telephone conversations in English, who state that “it is only rarely the case that a certain ordering and its reversal are both statistically associated combinations” (439). The aggregated probabilities of a DM x to occur as the first element in all possible combinations considered here allow us to rank all DMs according to their likelihood of preceding other DMs in two- or multiple-part combinations. In other words, DMs with a higher aggregated DTP are more likely to be followed by other DMs, and thus more often occurring as the first element in DM sequences than those with lower DTPs. Fig. 1 indicates the aggregated DTPs for each DM as the first element in a turn-initial sequence, showing a positional hierarchy that reflects the probability of any given DM to occur first in a sequence of DMs relative to all other DMs. The asterisks indicate the significance level deriving from a chi-square test, based on observed and expected position-based frequencies in turn-initial sequences.2 Oh has the highest aggregated DTP value (.9593), which means that it occurs almost exclusively as the first element in a sequence of DMs. At the opposite (lower) end we find then, which never occurs as the first element in a sequence of DMs at turn-beginnings. These extreme ends correspond to Lohmann and Koops' (2016) observations: in their ‘network model’, which reflects the co-occurrence and directionality of DMs in a chosen set of two-part sequences, oh always prefers initial position whereas then has the strongest tendency to occur in second position in collocating sequences. The data also show strong similarities to the “optimal sequencing hierarchy for DM sequences” in Koops and Lohmann's (2015) set since those DMs that rank highest, thus having a high probability to precede other DMs, are oh and well, followed by and > so > [or >] but > because, and then and you know forming the lower end. However, given that the authors operate with a smaller set of DMs, further comparisons cannot be made. A look at the upper end of the scale suffices to see that those DMs with the highest probability to occur first serve functions in the INTERACTION domain as they structure the transition from one speaker to another. These DMs are oh, well, OK, yeah, and yes, which express an immediate reaction to prior talk, such as acknowledgement and receipt of information (yeah, okay, yes), change of knowledge state (oh), or that the response options made relevant by a prior turn are inadequate (well, Schiffrin, 2 * ¼ p < .05, ** ¼ p < .01, *** ¼ p < .001. No indication of the significance level is given in those cases where the frequency in one or more of the cells is too low to yield statistically reliable values (which, however, does not necessarily mean that the relation between DTP and relative position in a sequence is insignificant). 10 Table 6 Frequency of DMs in turn-initial sequences and DTPs. 2nd Y 1st / actually actually anyway because but I mean I think no oh OK so then well yeah yes you know 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 .0196 0 1 .0196 0 7 .1372 0 2 .0645 1 .0196 0 0 2 .0392 1 .0666 0 1 .0322 1 .0196 0 0 6 .1176 1 .0666 0 0 0 3 .0588 2 .1333 0 2 .0645 0 0 0 1 .0322 3 .0588 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 .0088 0 1 .0088 0 1 .0065 3 .0265 0 0 2 .0134 3 .0125 4 .0754 1 .0067 39 .1625 0 4 .0261 6 .0530 1 .009 1 .0067 3 .0125 0 1 .0175 0 3 .0526 0 32 .1081 9 .0388 11 .0371 1 .0043 0 and 0 anyway 0 0 because 0 0 0 but 0 I mean 3 .0196 0 0 6 .0392 0 I think 0 0 0 no 1 .0067 5 .0208 0 2 .0134 0 0 oh OK so then well yeah yes you know ∑ (≠1st) 3 .0526 0 11 .0371 1 .0043 1 .0056 0 25:31 .8064 1 .0188 0 0 1 .0033 9 .0388 12 .067 1 .0303 26:51 .5098 0 0 2 .0177 0 21 .1372 0 0 1 .009 8 .0537 2 .0083 0 7 .0469 7 .0291 0 4 .0701 0 0 7 .0469 0 0 0 2 .035 0 0 28 .1879 7 .0291 6 .1132 0 0 0 5 .0877 0 0 7 .0236 2 .0086 3 .0167 0 3 .0101 36 .1551 22 .1229 0 27 .0912 13 .0560 8 .0446 0 10:15 .6666 21:25 .8400 102:153 .6666 90:113 .7964 2 .0067 0 0 3 .12 7 .0457 8 .0708 1 .0666 0 2 .0130 1 .0088 0 0 1 .0067 45 .1875 0 6 .025 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 49 .1655 5 .0216 12 .067 0 37 .125 0 0 0 2 .0086 0 2 .0067 10 .0431 0 0 0 0 3 .0101 8 .0345 9 .0502 0 106:110 .9636 88:149 .5906 4:240 .0166 20:53 .3773 37:57 .6491 1 .04 5 .0327 0 0 0 0 12 .2264 1 .0175 0 0 1 .0065 0 1 .009 3 .0201 47 .1958 9 .1698 0 0 0 0 1 .0065 1 .0088 1 .009 0 72 .3 1 .0188 1 .0175 0 17 .0574 0 24 .1034 9 .0502 0 15 .0837 0 0 26:26 1.0 94:296 .3175 112:232 .4827 88:179 .4916 0 32:33 .9696 P (1st) 6:31 .1935 25:51 .4901 5:15 .3333 4:25 .1600 51:153 .3333 23:113 .2035 4:110 .0363 61:149 .4093 236:240 .9833 33:53 .6226 20:57 .3508 0 0 202:296 .6824 120:232 .5172 91:179 .5083 1:33 .0303 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 and A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 11 Fig. 1. Aggregated DTPs showing the probability of turn-initial DMs to be the first element in a DM sequence. 1987: 103), i.e. when the speaker cannot fully endorse the content or implied meanings conveyed in the preceding turn. All these DMs are primarily backward-oriented in the sense that they indicate how the speaker relates to prior talk, e.g. weakly or strongly dis/agreeing or acknowledging receipt of information, before continuing with a conversational “next”. The next group of DMs serve the organization of discourse as they integrate turns into a coherent whole, i.e. they operate in the domain of DISCOURSE STRUCTURE. This holds for most forms referred to a “discourse markers” in the literature (Schiffrin, 1987; Fraser, 1999) and for the lexemes and, actually, anyway, because, but, I mean, no and so in the present study. These DMs are oriented toward an upcoming, new move in ongoing discourse, e.g. a topical shift or contrast (but), a conclusion (so), a move into a different topical direction (no), or the continuation with a new aspect (and).3 In their function of signaling a new move in discourse, they indicate how an upcoming turn is related to the prior turn or a non-verbalized, inferrable meaning deriving from prior talk, marking a boundary between both. The two DMs on the lower end of the scale, I think and you know, indicate how the upcoming turn is to be interpreted, namely as expressing the speaker's epistemic stance when prospectively marking a turn as conveying an opinion rather than a fact (I think) or as inviting the addressee to recognize both the relevance and the implications of the upcoming turn in a given sequential context (you know), i.e. as referring to meta-informational status. These functions clearly belong to the domain labeled COGNITION in Section 2. Based on these observations, the hierarchical organization of DMs according to their tendency to occur first in a sequence shown in Fig. 1 appears to correspond to a particular serialization order of the conversational functions they serve at the beginning of a turn. Table 7 shows the distribution of turn-initial DMs according to their functional domain and ranked according to their DTPs in decreasing order. Table 7 The serial order of turn-initial DMs. INTERACTION > DISCOURSE STRUCTURE > COGNITION backward-orientation forward-orientation forward-orientation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. and 7. no 8. so 9. but 10. anyway 11. I mean 12. actually 13. because 14. I think 15. you know 16. *then oh well OK yeah yes The model predicts that when several communicative tasks are given expression to at the beginning of a turn, the linearization order corresponds to a particular temporal logics: interaction management (turn-taking, transition from one speaker to another) is logically more relevant at a point in turn production that is closest to the prior turn, namely immediately adjacent, and thus having priority over signaling the kind of continuation, given that backward-orientation to prior talk should occur before going on with any kind of conversational ‘next’. Indicating the type of continuation in discourse (e.g. with a conclusion) relative to the preceding talk, in turn, is more relevant before providing information on how the turn itself 3 Note that no may serve as a DM to express immediate disagreement, but that in DM sequences it is almost exclusively used as a device to indicate a shift on the textual level from what has been expressed or implied before into a different direction, thus serving discourse structure (see example 3). 12 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 is to be understood (e.g. as expressing an opinion, as with I think): the first indicates how the speaker will continue, thus framing the upcoming turn in terms of discourse contingency, whereas the latter provides an interpretive cue as to the character of the turn itself, fine-tuning the addressee's orientation in preparation of the message. There is one clear exception to what looks like a fairly robust tendency, namely the distribution of the DM then. The DTP for then, which clearly has a text-linking function as it creates a relation between two turns based on logicaleargumentative sequentiality (Schiffrin, 1987: Ch. 8), is lower than that of all other DMs operating in the domain of DISCOURSE STRUCTURE and even lower than that of DMs serving functions in the domain of COGNITION, thus following all DMs in DM sequences (e.g. OK then, but then). A possible reason is that the occurrence of then as a DM is very low and perhaps bound to cooccurring DMs in order to distinguish it from the uses as a time adverb, which structures events on a time scale. Generally, the model in Table 7 predicts that those DMs that rank higher (due to higher DTPs) within a particular functional category statistically precede those that rank lower (resulting in sequences such as oh well yeah or but anyway). Note that in this model each of the three functional slots is optional and thus depending on the actual communicativeesequential context in which the production of an upcoming turn is embedded. It does therefore not predict or imply that any turn in spoken English is preceded by three DMs, or by any DM at all. However, it predicts what a DM sequence is most likely to look like when speakers produce at least two DMs in a series. Also note that the model does not indicate what the longest sequence of DMs may be as this depends on the kinds of communicative tasks a speaker wishes to give expression to at the beginning of a turn. A weakness of the model is that it makes predictions on combinations that are not or only rarely attested, e.g. OK you know. This is an effect deriving from the method of ranking DMs in terms of their aggregated DTPs, which generalize over all possible sequences and do not exclude unattested sequences (as these are simply corresponding to a zero value). Likewise, the schema does not account for some patterns that do occur in speech even though they deviate somewhat from the order that derives from the DTPs, such as no I mean so actually you know (ICE-GB S1A-029, 158-159). This is natural, given that the ranking order is based on probability measurements, i.e. it indicates a linearization order that is most probable, based on the combination of the 16 DMs. Probabilities only express what is most likely rather than representing fixed rules that exclude other linearization patterns. 6.2. Discourse marker sequences at the end of turns While turn-beginnings have received much attention in the literature as regards the use of DMs, turn-endings have only recently been subjected to a systematic investigation (e.g. Haselow, 2016, 2017: Ch. 4; Traugott, 2016; Degand and van Bergen, 2018). The study of DM sequences and possible ordering principles of DMs at the end of turns is still untilled soil. Table 8 indicates the frequency and the DTPs of each single DM combination at the end of turns attested in the ICE-GB, based on the set of DMs presented in Section 5. Table 8 Frequency of DMs in turn-final sequences and DTPs. 2nd Y 1st / then then though 0 anyway 0 actually though anyway actually tags GEs I think if-chunks yeah you know 1 .05 0 0 0 0 0 3 .15 0 0 0 7 .35 0 0 0 9 .45 13 .8125 2 .4 0 0 0 0 1 .3333 0 0 0 0 0 1 .3333 0 1 .0434 0 1 .0434 0 3 .1304 0 0 0 0 1 .2 0 0 0 tags 0 0 0 0 GEs 0 0 0 0 I think 0 0 0 ifchunks yeah 0 0 0 you know ∑ (≠1st) 2 .4 0 0 0 0 1 .2 0 9 .3913 2 .4 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0:20 0 2:16 .125 0:5 0 1:3 .3333 35:35 1.0 9:23 .3913 2:5 .4 0:0 0 4:4 1.0 0 1 .0625 0 0 P (1st) 20:20 1.0 14:16 .875 5:5 1.0 2:3 .6666 0:35 0 14:23 .6086 3:5 .6000 0:0 0 0:4 0 0:5 0 5:5 1.0 The data allow for the following conclusions. First, DM sequences are relatively rare at turn-endings, i.e. speakers are less likely to combine different DMs at the end of a turn, compared to turn-beginnings. One group of DMs e if-chunks e is even entirely unattested in sequences, i.e. if-chunks always occurred on their own in the ICE-GB. Secondly, some types of DMs A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 13 appear to close a turn for further DM production as they are not followed by any other DM (at least they are attested as turnfinal elements in the ICE-GB), namely tag questions, you know and yeah, whereas other DMs are often followed by further DMs, such as FPs and GEs. Fig. 2 shows the order of single DMs according to their likelihood of being followed by a further DM in descending order. Final then and anyway are most likely to be followed by other DMs if they occur in a sequence, given that their likelihood of being the first element in a sequence at turn-endings is highest, whereas e.g. tag questions are not followed by other DMs (hence their probability to be the first element in a sequence is zero). Note that if-chunks were excluded as they were not attested in turn-final sequences. Fig. 2. Aggregated DTPs showing the probability of turn-final DMs to be the first element in a DM sequence. Considering the functional domains within which the different DMs operate we can identify the following pattern. Final then, anyway, though, and actually clearly serve the organization of discourse as they have a retrospective connecting function in the sense that they establish a relation between two adjacent turns. This relational function has been defined as the most important class-defining functional feature of FPs in the literature (Haselow, 2012, 2013; Hancil et al., 2015), which are also referred to as “linking adverbials” (Biber et al., 1999: 889e892): FPs link the turn they accompany to an aspect of the preceding turn and mark the first as being motivated by the latter, hence they operate in the domain of DISCOURSE STRUCTURE. Final then, for instance, typically marks a turn as diverging from the speaker's expectations and as expressing an inference drawn from a preceding turn or discourse segment, as shown in (11). (11) 08 09 10 11 B: A: B: my grandmother was really uhm (.) helpful. who wasyou told her all about it then. yeah I di:d. [ICE-GB S1A-049] The information provided by speaker B leads A to infer that the state of affairs expressed in the turn (“you told her all about it”) is likely to be true. A thus treats B's utterance as a conditional protasis whose truth-value is, however, not hypothetical, but taken as a premise since B said it (‘if, as you say, p, q then?’). Final then establishes a conditionaleinferential link to the preceding turn (Haselow, 2012: 402e404). A second functional class comprises DMs that indicate how the turn just produced, or an aspect of it, is to be interpreted e not in relation to preceding talk, but as to the kind of utterance is represents. Their functional domain is COGNITION. This class includes GEs, the parenthetical I think, and you know. GEs may be used with two functions that can be labeled “referential” and “pragmatic” (Overstreet, 2014). In referential function, they serve as an interpretive cue expressing that there is potentially more to say, i.e. the speaker refers to a set of extra-linguistic entities denoted by the antecedent/s, typically “marking the preceding element as a member of a set” and instructing the listener to interpret this element “as an illustrative example of some more general case” (Dines, 1980: 22e23). Cognitively, they evoke a mental abstraction process leading to a , 2018). The “pragmatic” meanings of GEs are that of a contextually relevant ad hoc category (Barsalou, 1983; Mauri and Sanso hedge on informativeness and that of a “turn-punctor” (Cheshire, 2007; Overstreet, 1999: 103e104, 2014: 112): GEs indicate that a higher degree of precision is not required or intended at a particular point in discourse, and they signal that the turn is to interpreted as potentially complete in spite of informational incompleteness (Overstreet, 2014: 20). I think retrospectively marks an utterance as epistemically weak (Thompson and Mulac, 1991), usually as an opinion, and thus retrospectively changes the interpretation mode of an utterance e.g. from a fact to an opinion or an assumption. The DM is thus used as a hedging device, weakening or mitigating the force of a claim or a comment in such a way that it “leaves room for intervention by the interaction partner” (Nuyts, 2001: 165). The DM you know serves as a device to express the speaker's assumption that, based on shared knowledge or experience, his/her line of thinking or expressing a state of affairs is comprehensible for the addressee, that the latter is able to grasp the implications of a message just produced, and that there is no significant discrepancy between the mental world of the speaker and that of the addressee (Schourup, 1985: 102). 14 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 A third functional category comprises DMs that relate a turn to different aspects of the interaction between the speaker and the addressee. Tag questions facilitate addressee responses in that they offer the addressee to engage in ongoing interaction by eliciting a minimal affirmative response (e.g. hmm, yeah), that is, they invite the addressee to contribute to the discourse (Holmes, 1983; Tottie and Hoffmann, 2009: 146). Other tags are “attitudinal” (Tottie and Hoffmann, 2009: 145) in that they indicate the speaker's attitude, such as disapproval or solidarity, and they may be pragmatically challenging, softening, hortatory, or emphatic (e.g. I've told you not to touch it haven't I?). In both uses, the speaker implies a particular expectation on the side of the speaker, namely that the addressee will agree. Final yeah reconfirms the content of the prior speaker's utterance or an implied meaning, thus providing support for another speaker's utterance and marking a transitionrelevance place. In both cases, the DMs clearly target the addressee and prepare a next step in conversational interaction, potentially opening the floor for next-speaker contribution. If we rank-order the single DMs based on the DTPs in Table 8 and consider their functional value, we arrive at the linearization order shown in Table 9. Table 9 The serial order of turn-final DMs. DISCOURSE STRUCTURE > COGNITION > INTERACTION backward orientation backward-orientation forward-orientation 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. GEs 6. I think 7. you know 8. yeah 9. tag questions anyway then though actually This linearization pattern can, again, be explained with the temporal logics of communicative tasks to be performed at the moment in which they are produced. Discourse-structuring DMs should logically be (and are) closest to the current turn, and thus occur first in a sequence of DMs as they do not prepare a conversational “next”, but relate the turn to prior discourse. They provide a retrospective processing cue helping the addressee to integrate the turn into a mental model of discourse. Once the message has been allocated in ongoing discourse as being related to a preceding turn in a particular way, tasks relating to turn-interpretation or the interpretation of a part of it may e and often do e become relevant, which involves DMs operating the domain of COGNITION. Finally, speakers deal with tasks relating to a conversational ‘next’, i.e. which prepare an upcoming interactional step. Such interactional DMs are usually not followed by other DMs at turn-endings as they serve as the strongest indicators of a transitionrelevance place and are thus maximally relevant for interaction management, more precisely the distribution of speaker roles. 7. Discussion The analysis of the 26 DMs has shown that there is a strong bias toward specific orders when DMs occur in sequences at turnbeginnings and -endings. This suggests that turn-beginnings and -endings as “extra-clausal” parts of an utterance have a syntax of their own, which provides evidence for the existence of a component of grammar that encompasses forms that are not involved in clause-internal dependency relationships and that serve the structuration of language on a macrolevel. Such a grammar could be referred to as macrogrammar (Haselow, 2016, 2017) and be described in terms of linear (rather than linearehierarchical) ordering principles, based on the time course of communicative tasks to be performed in real-time speech production. The sequentiality of such tasks predicts that any given DM from a particular functional domain serving task x precedes a DM from a functional domain serving task y if giving expression to x is logically more relevant before expressing y. For the 26 DMs analyzed above, the temporalelinear order of communicative tasks at turn-beginnings and -endings that accounts for the highest probability of DM ordering is as shown in Fig. 3. The direction of the arrows indicates the main orientation of the respective tasks, which are either oriented backward (to a prior turn or a message just produced) or forward (to an upcoming turn or a next speaker). Fig. 3. Sequentiality of communicative tasks underlying the linear order of DMs. The order reflects a functional motivation underlying a speaker's cognitive orientation in discourse processing, and thus lends support to the DM Sequencing Hypothesis: the extreme ends of a turn (i.e. the very initial and very final slot) tend to serve the production of DMs that display orientation to the preceding or upcoming speaker and serve functions in the domain of INTERACTION. The slots following (at turn-beginnings) or preceding (at turn-endings) these DMs functionally serve tasks oriented toward the turn itself, namely its integration in surrounding discourse (within the functional domain of DISCOURSE STRUCTURE) and its interpretation, e.g. in terms of epistemic certainty (¼COGNITION). In this sense, the order of DMs within A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 15 sequences at turn-beginnings and -endings is, in some way, analogous: tasks related to another speaker's turn or participation are dealt with in the transition zones from one turn to another and from one speaker to another whereas tasks referring to the turn itself are closer to the message expressed in a turn if the full spectrum of different DMs is used. However, note that discourse (textual) organization follows interaction-related activities at the beginning of turns, but precedes all other functions at the end of turns, where the DMs serving this function occur first and thus closest to the turn just produced. A possible explanation is that since textual linking has an important framing function as it situates a turn in discourse-so-far, it occurs earliest (after backwardoriented tasks) when an upcoming turn is supposed to be established in order to provide an early processing cue, and earliest after the message of a turn has been produced (at the end of turns) in order to allow for the immediate integration of the turn into surrounding discourse. Finally, what is relevant for interpreting a turn itself follows discourse-organizing tasks. Coming back to the linearization principles discussed above we can now relate the conclusions deriving from the present study to the three main proposals concerning the motivation behind DM clustering that have been made in the literature (see Section 2.2). First, it has become clear that DM sequences are not merely strings of functionally similar DMs with a floor-holding function and “little function in themselves” (e.g. Aijmer, 2002: 31, 2004: 186). Given that DMs serve specific communicative functions, especially at turn-beginnings and -endings where speakers need to deal with a large set of generic tasks, the idea that DM sequences are merely a strategy to stall for time and to hold the floor and thus largely devoid of a particular function is untenable, even though occasional uses of DM sequences as a device to bridge a disfluency are, of course, possible. The data also make clear that co-occurrence in two- or multiple-part sequences does not only affect DMs of the same functional type (although such co-occurrences exist). Thus, sequencing is not merely motivated by one DM specifying or strengthening the meaning of the one with which it co-occurs, as has been suggested before e.g. by Oates (2000) or Fraser (2015). Most of the combinations studied here defy this explanation, given that the highest DTPs are attested with DMs that are functionally dissimilar (consider e.g. the high DTPs for sequences such as yeah I think or yeah but). In view of these observations, it appears more promising to translate the frequencies of co-occurrence and the ordering principles of DMs into empirical predictions on the types of communicative tasks that are often executed together at turnbeginnings and -endings, and their linearetemporal order. As shown above, it appears that these tasks are linearized according to their relation to surrounding discourse: what is relevant for structuring interaction (e.g. turn taking) occurs at the fringe of turns, interpretive cues for understanding the type of turn and its link to prior discourse are produced in close vicinity to the message itself. It is important to note that (i) the expression of the different communicative tasks described above is not required in all contexts and that (ii) DMs are not the only means to deal with these tasks, which explains why the extent to which speakers make use of DMs is always subject to contextual conditions. For instance, where the explicit indication of turn reception or of the link between turns is irrelevant, no use is made of DMs from these categories, e.g. when speakers complete another speaker's turn, as in line 15 in (12). (12) 12 13 14 15 16 17 / A: B: A: B: D: I I met her and <<unclear words>> you PIcked her up and DROPPed her did you . picked her up and dropped her yeah. only to pick her up again¼ ¼ I hope. (.) oh well if you've got her telephone number you picked her up. [ICE-GB S1A-020] It goes without saying that the functional categories for the DMs investigated in the present studies are rather broad. However, a more fine-grained differentiation is fraught with difficulties. The reason is that many DMs are used with subtle functional differences so that the categorical frame must necessarily be relatively gross. For instance, many DMs indicating the type of textual link between two turns do so on different dimensions, e.g. in terms of propositional or discursiveerhetorical relations. The DM but, for example, can be used to introduce a contrast to what has been expressed or implied in the prior turn, and thus to indicate a relationship on the propositional level, but it is also used on the discourseorganizing level to introduce a shift in discourse, e.g. a shift away from what has been discussed thus far (Bell, 1998). This is the case in (13): speaker D seeks to close a topic as he has no further information to contribute, rather than expressing a contrast to the content expressed in the preceding turn(s). (13) 104 105 106: 107 108 B: C: B: D: she's doing a PGCE.4 yes. [pathetic.] [sorry, ] but that's all I know about it really. [ICE-GB S1A-040] 4 PGCE ¼ Post-graduate certificate in education. 16 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 A further discourse-organizing use of but is that of a topic shift, as illustrated in (14), where the speaker does not produce a counterview, but seeks to shift the addressee's focus of attention to a different aspect of a topic under discussion. The speakers talk about reading books, D saying that he can hardly stop reading books once he has started a new one. (14) 237 238 239 240 A: D: A: I share your view but I just wonder why you think that's good. well I s- I suppose it's the writer (.) [that uh] [gets you so involved.] [yeah ] [but what you- ] what are you getting out of it. (.) [ICE-GB S1A-016] Again, the contrast projected by turn-initial but is to be found on the discourse rather than the propositional level as the speaker does not argue against D's assertion, but focuses on a different aspect (the general benefit or gain resulting from binch reading). So given the subtle functional differences of single DMs, which may act on several “planes of talk” (Schiffrin, 1987), the functional categorization suggested in this paper is only a gross simplification. Yet, the rather general categorical system yielded interesting results on the systematic ways in which DM are serialized and can thus serve as the basis for more finegrained analyses. 8. Conclusions and outlook The empirical analysis of DM sequences has shown that there is a strong tendency toward a particular serial order when DMs occur in sequences at the beginning and the end of turns. The order of DMs appears to reflect the temporal order of communicative tasks that are relevant for speakers at a given moment in interactive speech production, and thus offer insights into minute (perhaps serialized) cognitive processes involved in speech processing. The findings thus provide evidence for the DM Sequencing Hypothesis formulated earlier in this article. A promising step in finding further evidence for this hypothesis would be to expand the number of functional categories, based on a more fine-grained categorial system of DM functions, in order to sharpen our understanding of the serialization order of certain communicative functions and subfunctions in real-time speech production (see e.g. Crible, 2018, who annotated DMs in English and French following a fine-grained taxonomy). Furthermore, more data from comparative, crosslinguistic research are needed to explore the possible existence of more general cognitive processes underlying the stepby-step production of turns, independent of individual language systems. Given that conversation is interactive and, as far as we know, organized in adjacent turns in any language (Levinson, 2015), it is not unlikely that the communicative tasks that speakers need to deal with at turn-beginnings and -endings, as well as the serial order in which they are addressed, form some kind of “communicative universal” underlying human spoken interaction. Transcription conventions [] ¼ (.) (2.0) :,:: rea(hh)lly ABsolutely really word . , ? ¿ overlap and simultaneous talk latching micropause measured pause segmental lengthening according to duration laugh particles within talk strong, primary stress via loudness stress via pitch or amplitude produced softer than surrounding talk falling intonation (terminal pitch) continuing intonation rising intonation a rise stronger than mid-level but weaker than high-terminal pitch References Aijmer, Karin, 2002. English Discourse Particles. Evidence from a Corpus. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. Aijmer, Karin, 2004. Pragmatic markers in spoken interlanguage. Nordic Journal of English Studies 3 (1), 173e190. Auer, Peter, 1996. The pre-front field in spoken German and its relevance as a grammaticalization position. Pragmatics 6 (3), 295e322. Barsalou, Lawrence W., 1983. Ad hoc categories. Mem. Cognit. 11 (3), 211e227. Bell, David, 1998. Cancellative discourse markers: a core/periphery approach. Pragmatics 8 (4), 515e542. Biber, Douglas, Johansson, Stig, Leech, Geoffrey, Conrad, Susan, Finegan, Edward, 1999. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Pearson Education, Harlow. Blakemore, Diane, 2002. Relevance and Linguistic Meaning: the Semantics and Pragmatics of Discourse Markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Brinton, Laurel J., 2008. The Comment Clause in English: Syntactic Origins and Pragmatic Development. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Cheshire, Jenny, 2007. Discourse variation, grammaticalisation and stuff like that. J. SocioLinguistics 11 (2), 155e193. A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 17 Crible, Ludivine, 2017. Discourse markers and (dis)fluencies in English and French: variation and combination in the DisFrEn corpus. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 22 (2), 242e269. Crible, Ludivine, 2018. Discourse Markers and (Dis)fluency. Forms and Functions across Languages and Registers. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. Crible, Ludivine, Cuenca, María-Josep, 2017. Discourse markers in speech: characteristics and challenges for corpus annotation. Dialogue and Discourse 8 (2), 149e166. Cuenca, Maria Josep, Marín, Maria Josep, 2009. Co-occurrence of discourse markers in Catalan and Spanish oral narrative. J. Pragmat. 41, 899e914. Cuenca, María Josep, Crible, Ludivine, 2019. Co-occurrence of discourse markers in English: from juxtaposition to composition. J. Pragmat. 140, 171e184. Degand, Liesbeth, van Bergen, Geertje, 2018. Discourse markers as turn-transition devices: evidence from speech and instant messaging. Discourse Process 55 (1), 47e71. Degand, Liesbeth, Cornillie, Bert, Pietrandrea, Paola (Eds.), 2013. Discourse Markers and Modal Particles. Categorization and Description. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. , Nicole, 2014. Parentheticals in Spoken English: the Syntax-Prosody Relation. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Dehe Deppermann, Arnulf, 2013. Turn-design at turn-beginnings: multimodal resources to deal with tasks of turn-construction in German. J. Pragmat. 46 (1), 91e121. Diewald, Gabriele, 2013. ‘Same same but different’ e modal particles, discourse markers and the art (and purpose) of categorization. In: Degand, Liesbeth, Pietrandrea, Paola, Cornillie, Bert (Eds.), Discourse Markers and Modal Particles. Categorization and Description. John Benjamins, Amsterdam & Philadelphia, pp. 19e46. Dik, Simon C., 1997. The Theory of Functional Grammar. Part 2. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin. Dines, Elizabeth R., 1980. Variation in discourse e ‘and stuff like that’. Lang. Soc. 9 (1), 13e31. tane, 2013. Les associations de marqueurs discursifs. De la cooccurrence libre a la collocation. Linguist. Online 62 (5), 15e45 special issue on Dostie, Gae “Forms and Functions of Formulatic Construction Units in Authentic Conversation”. Fischer, Kerstin, 2000. From Cognitive Semantics to Lexical Pragmatics: the Functional Polysemy of Discourse Particles. Mouton de Gruyter, Berlin. Fischer, Kerstin (Ed.), 2006. Approaches to Discourse Particles. Elsevier, Amsterdam. Fraser, Bruce, 1999. What are discourse markers? J. Pragmat. 31 (7), 931e952. Fraser, Bruce, 2011. The sequencing of contrastive discourse markers in English. Int. Rev. Pragmat. 1 (2), 293e320. Fraser, Bruce, 2015. The combining of discourse markers e a beginning. J. Pragmat. 86, 48e53. lez, M., 2005. Pragmatic markers and discourse coherence relations in English and Catalan oral narrative. Discourse Stud. 77 (1), 53e86. Gonza Gregory, Michelle L., Raymond, William D., Bell, Alan, Fosler-Lussier, Eric, Jurafsky, Daniel, 1999. The effects of collocational strength and contextual predictability in lexical production. CLS 35, 151e166. Hancil, Sylvie, Haselow, Alexander, Post, Margje (Eds.), 2015. Final Particles. De Gruyter Mouton, Berlin. Hansen, Maj-Britt Mosegaard, 2006. A dynamic polysemy approach to the lexical semantics of discourse markers (with an exemplary analysis of French toujours). In: Fischer, Kerstin (Ed.), Approaches to Discourse Particles. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 21e41. Haselow, Alexander, 2012. Subjectivity, intersubjectivity and the negotiation of common ground in spoken discourse: final particles in English. Lang. Commun. 32 (3), 182e204. Haselow, Alexander, 2013. Arguing for a wide conception of grammar: the case of final particles in spoken discourse. Folia Linguist. 47 (2), 375e424. Haselow, Alexander, 2016. A processual view on grammar: macrogrammar and the final field in spoken syntax. Lang. Sci. 54, 77e101. Haselow, Alexander, 2017. Spontaneous Spoken English. An Integrated Approach to the Emergent Grammar of Speech. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Heine, Bernd, 2012. On discourse markers: grammaticalization, pragmaticalization, or something else? Linguistics 51 (6), 1205e1247. Heritage, John, 2013. Turn-initial position and some of its occupants. J. Pragmat. 57, 331e337. Holmes, Janet, 1983. The functions of tag questions. English Language Research Journal 3, 40e65. Jucker, Andreas H., Smith, Sara W., 1998. And people just you know like ‘wow’ e discourse markers as negotiating strategies. In: Jucker, Andreas H., Ziv, Yael (Eds.), Discourse Markers. Theory and Descriptions. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 171e201. Kapatsinski, Vsevolod M., 2005. Measuring the relationship of structure to use: determinants of the extent of recycle in repetition repair. Berkeley Linguistics Society 30, 481e492. Koops, Christian, Lohmann, Arne, 2015. A quantitative approach to the grammaticalization of discourse markers. Evidence from their sequencing behavior. Int. J. Corpus Linguist. 20 (2), 232e259. Lee-Goldman, Russel, 2011. No as a discourse marker. J. Pragmat. 43 (10), 2627e2649. Lenk, Uta, 1998. Marking Discourse Coherence: Functions of Discourse Markers in Spoken English. Narr, Tübingen. Levinson, Stephen, 2015. Turn-taking in human communication e origins and implications for language processing. Trends Cognit. Sci. 20 (1), 6e14. Levinson, Stephen C., Torreira, Francisco, 2015. Timing in turn-taking and its implications for processing models of language. In: Holler, Judith, Kendrick, Kobin, Casillas, Marisa, Levinson, Stephen (Eds.), Turn-Taking in Human Communicative Interaction. Frontiers Media, Lausanne, pp. 10e26. €ck, Lohmann, Arne, Koops, Christian, 2016. Aspects of discourse marker sequencing: empirical challenges and theoretical implications. In: Gunther, Kaltenbo Keizer, Evelien, Lohmann, Arne (Eds.), Outside the Clause. Form and Function of Extra-clausal Constituents. John Benjamins, Amsterdam, pp. 417e445. Maschler, Yael, 1994. Metalanguaging and discourse markers in bilingual conversation. Lang. Soc. 23, 325e366. Maschler, Yael, 2009. Metalanguage in Interaction: Hebrew Discourse Markers. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. , Andrea, 2018. Linguistic strategies for ad hoc categorization: theoretical assessment and cross-linguistic variation. Folia Linguist. 52, Mauri, Caterina, Sanso 1e35. McCarthy, Michael, 2003. Talking back: ‘Small’ interactional response tokens in everyday conversation. Res. Lang. Soc. Interact. 36 (1), 33e63. Nuyts, Jan, 2001. Epistemic Modality, Language and Conceptualization: A Cognitive-Pragmatic Perspective. John Benjamins, Amsterdam. Oates, Sarah Louise, 2000. Multiple discourse marker occurrence: creating hierarchies for natural language. In: Proceedings of the 3rd CLUK Colloquium, Brighton, pp. 41e45. Overstreet, Maryann, 1999. Whales, Candlelight, and Stuff like that. General Extenders in English Discourse. Oxford University Press, New York. Overstreet, Maryann, 2014. The Role of Pragmatic Function in the Grammaticalization of English General Extenders. Pragmatics vol. 24 (1), 105e129. Pichler, Heike, Levey, Stephen, 2011. In search of grammaticalization in synchronic dialect data: general extenders in Northeast England. Engl. Lang. Linguist. 15 (3), 441e471. Pons Bordería, Salvador, 2018. The combination of discourse markers in spontaneous conversations: keys to undo a gordian knot. Rev. Romane 53 (1), 121e158. Redeker, Gisela, 2006. Discourse markers as attentional cues at discourse transitions. In: Fischer, Kerstin (Ed.), Approaches to Discourse Particles. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp. 339e358. Rühlemann, Christoph, 2017. Integrating corpus-linguistic and conversation-analytic transcriptions in XML: the case of backchannels and overlap in storytelling interaction. Corpus Pragmatics 1, 201e232. Schegloff, Emanuel A., 1996. Turn organization: one intersection of grammar and interaction. In: Ochs, Elinor, Schegloff, Emanuel A., Thompson, Sandra A. (Eds.), Interaction and Grammar. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp. 52e133. Schegloff, Emanuel A., 2007. Sequence Organization in Interaction: A Primer in Conversation Analysis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Schiffrin, Deborah, 1987. Discourse Markers. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Schourup, Lawrence, 1985. Common Discourse Particles in English Conversation. Garland, New York. Schourup, Lawrence, 1999. Discourse markers. Lingua 107, 227e265. Schourup, Lawrence, 2001. Rethinking well. J. Pragmat. 33, 1025e1060. 18 A. Haselow / Journal of Pragmatics 146 (2019) 1e18 Stalnaker, Robert, 2002. Common ground. Ling. Philos. 25 (5e6), 701e721. Thompson, Sandra A., Mulac, Anthony J., 1991. The discourse conditions for the use of the complementizer ‘that’ in conversational English. J. Pragmat. 15, 237e251. Tottie, Gunnel, Hoffmann, Sebastian, 2006. Tag questions in British and American English. J. Engl. Linguist. 34 (4), 283e311. Tottie, Gunnel, Hoffmann, Sebastian, 2009. Tag questions in English e the first century. J. Engl. Linguist. 37, 130e161. Traugott, Elizabeth C., 2016. On the rise of types of clause-final pragmatic markers in English. J. Hist. Pragmat. 17 (1), 26e54. Alexander Haselow is Assistant Professor of English Linguistics at the University of Münster. His current research focuses on the cognitive, dialogic and neural mechanisms underlying the production and perception of speech in real time, and how these can be integrated into a usage-based model of speech production. He is the author of Spontaneous Spoken English (Cambridge, 2017), co-editor of Final Particles (De Gruyter Mouton, 2015), and he has published various articles on structural and cognitive aspects of spontaneous speech in international, peer-reviewed journals.