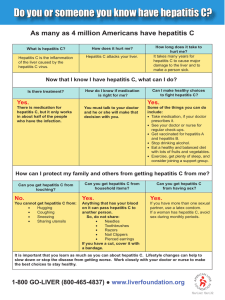

The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital Founded by Richard C. Cabot Eric S. Rosenberg, M.D., Editor Virginia M. Pierce, M.D., David M. Dudzinski, M.D., Meridale V. Baggett, M.D., Dennis C. Sgroi, M.D., Jo‑Anne O. Shepard, M.D., Associate Editors Alyssa Y. Castillo, M.D., Case Records Editorial Fellow Emily K. McDonald, Sally H. Ebeling, Production Editors Case 15-2019: A 55-Year-Old Man with Jaundice Esperance A. Schaefer, M.D., M.P.H., Mark A. Anderson, M.D., Arthur Y. Kim, M.D., and Maroun M. Sfeir, M.D. Pr e sen tat ion of C a se Dr. Joseph D. Planer (Medicine): A 55-year-old man with a history of opioid use disorder and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection presented to this hospital with jaundice. Four months before the current presentation, the patient was released from prison after a 2-year incarceration. After he left prison, he resumed injecting heroin and had three episodes of overdose. He was evaluated at another hospital for symptoms of depression and was admitted for psychiatric treatment. During that admission, sublingual buprenorphine–naloxone therapy was initiated, and the patient was discharged. One day after discharge and 5 weeks before the current presentation, headache, body aches, sweats, diarrhea, and nausea developed. The patient presented to a clinic for substance use disorder that is affiliated with the other hospital and reported that he had been unable to obtain sublingual buprenorphine–naloxone from a pharmacy after discharge. The temperature was 36.6°C, the pulse 70 beats per minute, and the blood pressure 100/68 mm Hg. The weight was 72 kg. He appeared to be restless, but the remainder of the physical examination was normal. Urine toxicologic screening was positive for buprenorphine, norbuprenorphine, and norfentanyl; buprenorphine–naloxone therapy was resumed. Three weeks before the current presentation, dark urine and light-headedness developed and did not improve with increased fluid consumption. The patient also noticed slow thinking and arthralgias in the hands, wrists, and elbows. He was evaluated by a new primary care provider. The temperature was 36.7°C, the pulse 53 beats per minute, and the blood pressure 104/66 mm Hg. The joints of the hands, wrists, and elbows were normal. The neurologic examination was normal, as was the remainder of the physical examination. Blood levels of electrolytes and glucose were normal, as were the complete blood count, differential count, and results of renal-function tests. Urinalysis revealed clear, dark-yellow urine, with a specific gravity of 1.020 (reference range, 1.00 to 1.030), a pH of 7.5 (reference range, 5.0 to 9.0), trace ketones (reference value, negative), and 2+ urobilinogen n engl j med 380;20 nejm.org From the Departments of Medicine (E.A.S., A.Y.K.), Radiology (M.A.A.), and Pathology (M.M.S.), Massachusetts General Hospital, and the Departments of Medicine (E.A.S., A.Y.K.), Radiology (M.A.A.), and Pathology (M.M.S.), Har‑ vard Medical School — both in Boston. N Engl J Med 2019;380:1955-63. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcpc1900592 Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 1955 The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l of m e dic i n e Table 1. Laboratory Data. Variable Reference Range* Prothrombin time (sec) 11.5–14.5 20.0 0.9–1.1 1.7 Prothrombin-time international normalized ratio 3 Wk before Presentation On Presentation Alanine aminotransferase (U/liter) 10–55 1299 2698 Aspartate aminotransferase (U/liter) 10–40 779 2869 0.0–1.0 1.7 21.6 Bilirubin (mg/dl)† Total Direct 0–0.4 Alkaline phosphatase (U/liter) 18.6 45–115 213 150 Total 6.0–8.3 6.7 5.4 Albumin 3.3–5.0 4.0 3.4 Globulin 1.9–4.1 2.7 2.0 Negative Positive Positive <15 68,172 <15 Protein (g/dl) C-reactive protein (mg/liter) <8.0 Hepatitis C virus antibody Hepatitis C virus RNA (IU/ml) Human immunodeficiency virus p24 antigen and type 1 and type 2 antibodies 31.5 Negative Negative *Reference values are affected by many variables, including the patient population and the laboratory methods used. The ranges used at Massachusetts General Hospital are for adults who are not pregnant and do not have medical conditions that could affect the results. They may therefore not be appropriate for all patients. †To convert the values for bilirubin to micromoles per liter, multiply by 17.1. (reference value, negative). Other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. One week before the current presentation, the patient noticed yellowing of the eyes and skin. One week later, he was seen by his primary care provider and was immediately transported by ambulance to the emergency department of this hospital for evaluation. On evaluation, the patient reported 2 weeks of anorexia, malaise, nausea with dark-brown emesis, profuse nonbloody watery diarrhea, intermittent abdominal cramping, poor sleep, blurry vision, and episodes of forgetfulness and loss of concentration. He had no fevers, chills, bleeding, or pulmonary or genitourinary symptoms and had no sick contacts. There was a history of osteoarthritis, depression, and anxiety. HCV infection had been diagnosed but not treated while the patient was incarcerated. He reported that when he used intravenous heroin, he did not reuse, share, or lick needles. Allergies included penicillin, aspirin, and sulfonamide-containing 1956 n engl j med 380;20 antibiotic agents. The only medication was sublingual buprenorphine–naloxone. The patient was divorced and had no children. He had not been sexually active in 2 years. He was born in the northeastern United States and had not traveled outside the country. Since his release from prison, he was unemployed, homeless, and sleeping in a shelter. He had no known exposure to rodents or rodent excreta. He smoked cigarettes daily and had done so for 20 years. He had previously consumed 2 liters of vodka daily but had quit 6 years earlier. His parents were deceased; he was estranged from his siblings, and their medical history was unknown. On physical examination, the temperature was 36.3°C, the pulse 57 beats per minute, the blood pressure 113/72 mm Hg, the respiratory rate 18 breaths per minute, and the oxygen saturation 97% while the patient was breathing ambient air. The weight was 68 kg. The patient appeared jaundiced and had marked scleral icterus. The mucous membranes were moist, and there nejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Case Records of the Massachuset ts Gener al Hospital was no cervical lymphadenopathy. The abdomen was soft and nondistended, with no evidence of ascites. There was mild tenderness on palpation of the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, with no hepatosplenomegaly. The patient had no gynecomastia, caput medusae, or spider angiomas. He was alert and fully oriented and had no asterixis. There was no rash or leg edema. The remainder of the physical examination was normal. Blood levels of electrolytes, glucose, and lipase were normal, as were the complete blood count, differential count, and results of renal-function tests. Serum toxicologic screening did not detect acetaminophen, salicylates, tricyclics, or ethanol. Other laboratory test results are shown in Table 1. Dr. Mark A. Anderson: Limited ultrasonography of the right upper quadrant (Fig. 1) revealed no bile-duct dilatation, a patent main portal vein with hepatopetal flow, and normal hepatic parenchymal echotexture. Diffuse, hypoechoic gallbladder-wall thickening was present, without gallbladder distention, cholelithiasis, or pericholecystic fluid. Murphy’s sign was negative. There was trace perihepatic ascites. Dr. Planer: Additional diagnostic tests were performed. Differ en t i a l Di agnosis Dr. Esperance A. Schaefer: The first question to address in the assessment of this patient is whether his syndrome is due to acute liver injury or acute-on-chronic liver failure in the presence of established cirrhosis.1 The patient had a history of heavy alcohol use and HCV infection. In patients with chronic HCV infection, fibrosis can progress slowly, with cirrhosis developing after 20 years in 16%; however, the progression of fibrosis is influenced by host and environmental factors and is accelerated by alcohol use.2 Clinical clues that point away from cirrhosis in this case include the absence of gynecomastia and spider angioma on physical examination, the normal platelet count, and the absence of nodular liver contour and splenomegaly on ultrasonography.3 The magnitude of his elevated alanine aminotransferase level also argues against advanced liver disease, because it suggests the presence of a substantial volume of viable hepatocytes that are susceptible to injury, a feature that is uncommonly seen in cirrhosis. n engl j med 380;20 In the absence of underlying cirrhosis, it is critical to rule out acute liver failure. In adults, the diagnosis of acute liver failure requires synthetic dysfunction with an international normalized ratio of more than 1.5, as well as a disease duration of less than 26 weeks and the presence of hepatic encephalopathy. This patient reported mild cognitive change, but his examination did not reveal hepatic encephalopathy. Thus, his clinical diagnosis at presentation is most consistent with severe acute liver injury, rather than acute liver failure. A long-held dogma regarding the differential diagnosis of severe acute liver injury is that most cases are due to vascular, viral, or toxic causes. A recent multicenter study examined the causes of severe acute liver injury in patients with an aspartate aminotransferase or alanine aminotransferase level of more than 1000 U per liter and confirmed the leading causes to be ischemic hepatitis, pancreaticobiliary disease, drug-induced liver injury, and viral hepatitis.4 Ischemic Hepatitis Does this patient have a vascular or ischemic process that is causing acute liver injury? Ische­ mic hepatitis is defined as a decrease in hepatic blood flow that results in hepatocyte death and necrosis. This condition is commonly seen in critically ill patients, and in many cases, a clear hypotensive episode is not documented, which suggests that the insulting event may be fleeting or subclinical.5 Recent data further suggest that elevated central venous pressure and cardiac pressures on the right side are important predisposing factors.6 The elevation in aminotransferase levels tends to be dramatic but brisk, with the rise and fall occurring over a period of 24 to 48 hours, and it is usually followed by a rise in the bilirubin level. This patient does not have ischemic injury, given the sustained and persistent rise in the alanine aminotransferase level over a period of several weeks. Pancreaticobiliary Disease The absence of bile-duct dilatation, gallstones, and pancreatic abnormality on ultrasonography provides evidence against a pancreaticobiliary cause of this patient’s liver injury. The magnitude of hyperbilirubinemia and the kinetics of elevation in aminotransferase levels are also not nejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 1957 The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l A of m e dic i n e B D C Liver FF E 1958 F n engl j med 380;20 nejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Case Records of the Massachuset ts Gener al Hospital Figure 1 (facing page). Abdominal Ultrasound Images. Grayscale images (Panels A, B, E, and F) and color Doppler images (Panels C and D) of the right upper quadrant show no intrahepatic or extrahepatic bileduct dilatation (Panels A and B), a patent main portal vein with flow in the correct direction (Panel C, arrow), trace perihepatic ascites (Panel D, arrows), and a col‑ lapsed gallbladder with diffuse, hypoechoic wall thicken‑ ing (Panels E and F, plus signs). FF denotes free fluid. suggestive of biliary disease; the alanine aminotransferase level tends to rise and fall rapidly, and it is uncommon to have a peak bilirubin level of more than 10 mg per deciliter (171 μmol per liter).7 Drug-Induced Liver Injury Drug-induced liver injury must be considered in all cases of severe acute liver injury or failure; studies have determined it to be the most common cause of acute liver failure in the United States and most of Europe.8 In a large study that involved patients with this condition, severe hepatocellular disease was common, with a mean alanine aminotransferase level of 1200 U per liter and a mean international normalized ratio of 1.6. The leading offending agents were antibiotics and herbal and dietary supplements.9 In this case, the only new medication was buprenorphine– naloxone, which is an exceedingly rare cause of drug-induced liver injury. One report identified buprenorphine–naloxone as the cause of severe liver injury in two patients with chronic HCV infection; the drug had been injected at high doses, and symptomatic hepatitis had occurred within 4 days after the injection.10 In this patient, there is no reported history of use of injection buprenorphine–naloxone, and the symptoms had appeared just 1 day after initiation of the medication. Viral Hepatitis This patient’s clinical presentation is strongly suggestive of acute viral hepatitis. The acute viral infections that most commonly cause severe liver injury are HCV infection (in 8.0% of cases) and hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection (in 2.1% of cases). Hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis delta virus (HDV), Epstein–Barr virus, and cytomega- n engl j med 380;20 lovirus infections are much less common causes (in 0.3% of cases combined).4 These findings are in keeping with 2016 data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which showed 41,000 new cases of HCV infection, 20,900 new cases of HBV infection, and 4000 new cases of HAV infection.11 Acute HCV Infection Symptoms associated with acute HCV infection occur approximately 9 weeks after exposure. There is a very low level of viremia in the first 2 months after infection, followed by a brisk and exponential increase in viremia over a period of 8 to 10 days. In the subsequent phase, the host immune system responds to the viremia: the aminotransferase levels rise, the HCV RNA viral load plateaus, and symptoms develop.12 Symptoms include fatigue, abdominal pain, jaundice, muscle and joint aches, mood disturbances, and diarrhea.13 During this phase, the viral load and alanine aminotransferase level fluctuate. The viral load may be intermittently or persistently negative. It is common for the alanine aminotransferase level to be more than 10 times the upper limit of the normal range, but marked hyperbilirubinemia and an elevated prothrombin time are rare.14 Could this patient have acute HCV infection? Although he reportedly had a history of HCV infection, we have not seen an HCV viral load obtained before this presentation. A positive test for HCV antibodies alone suggests previous exposure but does not confirm a chronic infection. An estimated 25% of persons with exposure to HCV have successful viral clearance; female sex, symptomatic infection, and favorable host genetic factors are associated with spontaneous clearance.15 A landmark finding in the understanding of the immune response to HCV was the identification of single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the IL28B gene that are strongly associated with both interferon response16-18 and spontaneous viral clearance.19-21 Such favorable singlenucleotide polymorphisms have also been shown to increase the clearance of repeat infection. In the absence of chronic HCV infection, many of the features in this case are strongly suggestive of acute HCV infection. The patient reported that nejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 1959 The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l he had not shared needles, but sharing of flushes, cooking apparatus, or other elements during injection may pose a risk of exposure. The time frame from presumed exposure, the diffuse symptom complex, and the fluctuating viral load would support a diagnosis of acute HCV infection; however, the degree of hyperbilirubinemia and the coagulopathy are not characteristic of this diagnosis.14 Acute HBV Infection The clinical presentation and outcome of acute HBV infection are strongly influenced by the patient’s age; in neonates, viral clearance is exceedingly rare, occurring in less than 5% of cases, whereas in adults, the infection is successfully controlled in more than 95% of cases.22 The virus itself is noncytopathic, and the symptoms and liver injury are consequences of the host immune response. Liver failure is rare but occurs in approximately 1% of cases. Even in the absence of liver failure, liver injury can be severe; in one case series, the mean alanine aminotransferase level was 1419 U per liter, and the mean bilirubin level 6.5 mg per deciliter (111 μmol per liter).23 In classic cases of HBV infection, there is a subacute rise and fall in the alanine aminotransferase level, occurring over a period of 2 to 8 weeks, with the viral DNA and surface antigen levels falling after the alanine aminotransferase level has peaked. The hallmark serologic test for acute HBV infection is the test for IgM antibodies to HBV core antigen, which can remain positive for up to 6 months after exposure. If the patient’s status regarding previous exposure to HBV is unknown, it can be challenging to distinguish reactivation of chronic HBV infection from new acute HBV infection. Reactivation occurs when the virus transitions from a state of low viral replication to a period of increased replication that is accompanied by a vigorous immune response and is clinically manifested by jaundice or decompensated liver disease. Peak alanine aminotransferase and bilirubin levels tend to be lower in patients with reactivation than in patients with primary infection, and IgM antibodies to HBV core antigen are present in less than half of patients with reactivation.24 In this patient, hepatitis was more severe than is commonly seen in persons with acute HBV infection, and this finding raises the question of whether additional factors contributed to 1960 n engl j med 380;20 of m e dic i n e his condition. Underlying HCV infection can precipitate a more severe clinical presentation of HBV infection; in one small case series, severe hepatitis was observed in 34.5% of the patients with HCV and HBV coinfection, as compared with 6.9% of the patients with acute HBV infection alone.25 All the patients with preexisting HCV infection had an undetectable HCV viral load 3 to 6 weeks after the onset of symptoms, a finding that suggests that infection with another hepatotropic virus may prompt a strong anti-HCV immune response that results in viral clearance.26,27 The clinically significant decline in this patient’s HCV viremia supports the possibility of a superinfection with a second virus. However, it does not provide insight into which viral agent may be involved. Acute HDV Infection What other factors could explain this patient’s severe acute liver injury? HDV infection is dependent on and exacerbates HBV infection. There are two clinical patterns of infection with HDV: coinfection, in which exposure to HDV and to HBV are simultaneous; and superinfection, in which acute HDV infection occurs in a person with established chronic HBV infection. In cases of coinfection, HDV infection relies on the successful development of HBV infection, which is uncommon in adults, and thus chronic coinfection is rare. The clinical presentation of acute coinfection varies in severity. Superinfection is most likely to be clinically severe and is thought to be a major cause of acute liver failure in patients with chronic HBV infection. In cases of superinfection, chronic coinfection is commonly established. As with acute HBV infection, the diagnosis of HDV infection is made with the use of serologic tests. In patients with acute coinfection, tests for IgM antibodies to both HDV and HBV core antigen are positive. The HBV DNA level is more commonly elevated in patients with acute coinfection than in patients with superinfection, in whom the HBV DNA level can be quite low because of an anti-HDV immune response.28 HDV infection remains rare in the United States. Among the persons who participated in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) from 1999 to 2012 and had positive tests for HBV core antibodies and surface antigen, the estimated overall prevalence of HDV infection was 0.02%.29 NHANES data obnejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Case Records of the Massachuset ts Gener al Hospital tained from 2011 to 2016 showed a slightly higher prevalence of HDV infection, of 0.11%.30 However, the NHANES did not include several highrisk populations, such as homeless and incarcerated persons. In addition, the prevalence of HDV infection may be higher among persons who inject drugs. In one cohort of persons who inject drugs, testing for HDV antibodies and RNA was performed in participants who had a positive test for HBV surface antigen, and HDV infection was identified in 35.6% of the participants with chronic HBV infection.31 Thus, although the overall prevalence of HDV infection is very low, the rate may be higher in certain high-risk cohorts. HAV Infection HAV infection is a classic cause of severe acute viral hepatitis. Similar to HBV infection, HAV infection has a clinical presentation that varies according to the patient’s age; children are often asymptomatic, whereas more than 70% of adults have symptoms, such as fever, malaise, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort, that last 2 to 8 weeks. Jaundice is usually short-lived, occurring over a period of less than 2 weeks, but a small fraction of patients may have a relapsing course.32 Before 2017, only 1600 cases of HAV infection were reported annually, due in large part to a highly effective vaccine. However, since 2017, a multistate outbreak of HAV infection has led to a sharp rise in the number of cases, with 7000 cases reported in 12 states33 and 350 outbreak-associated cases reported in the state of Massachusetts by early 2019. Of the patients who had these outbreak-associated cases, 48% were homeless, 90% were engaged in illicit drug use, and 63% had HCV coinfection.34 In light of this epidemic, HAV infection is an important consideration in this case. However, in this patient, jaundice had progressed over a period of 5 weeks, whereas in patients with HAV infection, icteric hepatitis lasts less than 2 weeks. Summary The diagnosis in this case will depend entirely on the results of serologic tests. In the presence of severe acute liver injury and probable viral hepatitis, a biopsy is unlikely to yield additional information.35 This patient probably has chronic HCV infection. However, the severity and duration of the acute icteric hepatitis are most consistent with acute HBV infection, which, superimposed n engl j med 380;20 on chronic HCV infection, can lead to severe hepatitis. Because the patient’s presumed exposure was injection drug use, HDV coinfection should be considered; however, since it occurs rarely, it is unlikely in this case. Dr . E sper a nce A . Sch a efer’s Di agnosis Acute hepatitis B virus infection in the presence of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Pathol o gic a l Discussion Dr. Maroun M. Sfeir: This patient was tested for HAV and hepatitis E virus. Both tests were negative, ruling out these two causes of acute viral hepatitis. Testing for HBV was also performed. The patient’s blood tests were negative for HBV surface antibodies and positive for HBV surface antigen, IgM antibodies to HBV core antigen, and HBV e antigen. These test results, in conjunction with a plasma HBV DNA level of 999,000 IU per milliliter, are diagnostic of acute HBV infection. A negative test for HBV surface antibodies is expected in cases of acute HBV infection. Finally, because HDV relies on HBV for replication, a test for HBV surface antigen, which constitutes the protein coat of the defective virus, would be positive during HDV infection.36 As noted previously, HBV and HDV coinfection occurs when a patient becomes infected with the two viruses simultaneously. HDV antibodies are detectable 3 months after exposure in 85% of patients with coinfection and decline to undetectable levels after the infection resolves, as reflected by a rise in the level of HBV surface antibodies.36,37 Serum HDV RNA is detected early but is transient during HBV and HDV coinfection. This patient’s blood tests were positive for HDV RNA viremia, confirming the diagnosis of acute HDV infection. Taken together, these results are diagnostic of acute HBV and HDV coinfection. Discussion of M a nagemen t a nd Fol l ow-up Dr. Arthur Y. Kim: Daily measurements of the alanine aminotransferase level and prothrombin time revealed a steady decline. In immunocompetent adults, acute HBV infection typically renejm.org May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 1961 The n e w e ng l a n d j o u r na l solves spontaneously, and antiviral treatment is usually not given during this stage.38 However, because this patient had ongoing symptoms and a markedly elevated HBV viremia and there were concerns regarding the rapid progression of liver disease due to multiple viral infections, therapy with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate was initiated on hospital day 4. The bilirubin level peaked at 24.6 mg per deciliter (421 μmol per liter) on hospital day 6; the patient felt better and was discharged. One month after presentation, the alanine aminotransferase level had normalized. Six months after discharge, the patient continued to receive tenofovir, and the HBV DNA level had declined to 462 IU per milliliter. The HCV RNA viral load rebounded to 76,200 IU per milliliter. The patient therefore had triple infection with HBV, HCV, and HDV. Currently in the United States, particularly in the northeast region, there is a “syndemic” (synergistic epidemic) of opioid use and associated infectious diseases, with each overlapping epidemic further exacerbating the prognosis and burden of disease.39 Unstable housing is an additional factor, as observed in this case. HCV infection is common in persons who inject drugs, whereas HBV infection is more rare. Exposure to HDV in persons with chronic HBV infection is an increasing concern,30,31 and as mentioned previously, the prevalence of HDV is particularly high among persons with HBV infection who inject drugs.31 Moreover, the rates of bacterial infections, HAV infection, and human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection have been rising in this population.34,40 Responses to such a syndemic are multipronged and include addressing social factors such as homelessness, preventing certain infectious diseases (e.g., HAV and HBV) by means of vaccination, and enhancing access to opioidagonist therapy and syringe-services programs. References 1. Hernaez R, Solà E, Moreau R, Ginès P. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: an update. Gut 2017;66:541-53. 2. Westbrook RH, Dusheiko G. Natural history of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2014;61: Suppl:S58-S68. 3. Udell JA, Wang CS, Tinmouth J, et al. Does this patient with liver disease have cirrhosis? JAMA 2012;307:832-42. 4. Breu AC, Patwardhan VR, Nayor J, et al. A multicenter study into causes of severe 1962 of m e dic i n e Although the interactions of all three viruses in this patient are complex, treatment should be considered for all three, because each chronic infection contributes to the risk of future complications, such as cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. HCV is considered to be curable with safe and effective combination antiviral therapies that are typically administered for 8 or 12 weeks. Trials of such agents in patients with a recent history of intravenous drug use have shown excellent cure rates and relatively low reinfection rates.41,42 HDV is a defective virus that depends on the presence of HBV. The patient’s antiviral therapy directed against HBV should therefore be continued, but it is unlikely to resolve the HDV. Available therapies for HDV are based on interferonalfa but are associated with substantial side effects and have had varied results. New experimental agents, such as prenylation inhibitors and entry inhibitors, show promise but are not yet approved for use.43 Ten months after presentation, the patient’s housing had stabilized, he was no longer using injection drugs, and he was employed. He continued to be adherent to the tenofovir and buprenorphine–naloxone regimens. He had yet to be treated specifically for either HCV or HDV infection. Fina l Di agnosis Acute hepatitis B virus and hepatitis delta virus coinfection in the presence of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. This case was presented at the Medical Case Conference. Dr. Kim reports receiving consulting fees from BioMarin. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. acute liver injury. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018 August 10 (Epub ahead of print). 5. Tapper EB, Sengupta N, Bonder A. The incidence and outcomes of ischemic hepatitis: a systematic review with metaanalysis. Am J Med 2015;128:1314-21. 6. Lightsey JM, Rockey DC. Current concepts in ischemic hepatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2017;33:158-63. 7. Bangaru S, Thiele D, Sreenarasim- n engl j med 380;20 nejm.org haiah J, Agrawal D. Severe elevation of liver tests in choledocholithiasis: an uncommon occurrence with important clinical implications. J Clin Gastroenterol 2017;51:728-33. 8. Hadem J, Tacke F, Bruns T, et al. Etiologies and outcomes of acute liver failure in Germany. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10(6):664-669.e2. 9. Chalasani N, Bonkovsky HL, Fontana R, et al. Features and outcomes of 899 pa- May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. Case Records of the Massachuset ts Gener al Hospital tients with drug-induced liver injury: the DILIN prospective study. Gastroenterology 2015;148(7):1340-1352.e7. 10. Peyrière H, Tatem L, Bories C, Pageaux GP, Blayac JP, Larrey D. Hepatitis after intravenous injection of sublingual buprenorphine in acute hepatitis C carriers: report of two cases of disappearance of viral replication after acute hepatitis. Ann Pharmacother 2009;43:973-7. 11. Viral hepatitis:2016 surveillance. Atlanta:Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016 (https://www.cdc.gov/ hepatitis/statistics/2016surveillance/index .htm). 12. Sharma SA, Feld JJ. Acute hepatitis C: management in the rapidly evolving world of HCV. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2014;16: 371. 13. Santantonio T, Sinisi E, Guastadi­ segni A, et al. Natural course of acute hepatitis C: a long-term prospective study. Dig Liver Dis 2003;35:104-13. 14. Loomba R, Rivera MM, McBurney R, et al. The natural history of acute hepatitis C: clinical presentation, laboratory findings and treatment outcomes. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2011;33:559-65. 15. Grebely J, Page K, Sacks-Davis R, et al. The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology 2014;59:109-20. 16. Ge D, Fellay J, Thompson AJ, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B predicts hepatitis C treatment-induced viral clearance. Nature 2009;461:399-401. 17. Suppiah V, Moldovan M, Ahlenstiel G, et al. IL28B is associated with response to chronic hepatitis C interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy. Nat Genet 2009; 41: 1100-4. 18. Tanaka Y, Nishida N, Sugiyama M, et al. Genome-wide association of IL28B with response to pegylated interferon-alpha and ribavirin therapy for chronic hepatitis C. Nat Genet 2009;41:1105-9. 19. Page K, Mirzazadeh A, Rice TM, et al. Interferon lambda 4 genotype is associated with jaundice and elevated aminotransferase levels during acute hepatitis C virus infection: findings from the InC3 Collaborative. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3(1):ofw024. 20. Thomas DL, Thio CL, Martin MP, et al. Genetic variation in IL28B and spontaneous clearance of hepatitis C virus. Nature 2009;461:798-801. 21. Tillmann HL, Thompson AJ, Patel K, et al. A polymorphism near IL28B is associated with spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus and jaundice. Gastroenterology 2010;139(5):1586-92, 1592.e1. 22. Trépo C, Chan HL, Lok A. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet 2014;384:2053-63. 23. Du X, Liu Y, Ma L, et al. Virological and serological features of acute hepatitis B in adults. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017; 96(7):e6088. 24. Kunnathuparambil SG, Vinayakumar KR, Varma MR, Thomas R, Narayanan P, Sreesh S. Bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase and platelet count score: a novel score for differentiating patients with chronic hepatitis B with acute flare from acute hepatitis B. Ann Gastroenterol 2014; 27:60-4. 25. Sagnelli E, Coppola N, Pisaturo M, et al. HBV superinfection in HCV chronic carriers: a disease that is frequently severe but associated with the eradication of HCV. Hepatology 2009;49:1090-7. 26. Shin EC, Sung PS, Park SH. Immune responses and immunopathology in acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16:509-23. 27. Coffin CS, Mulrooney-Cousins PM, Lee SS, Michalak TI, Swain MG. Profound suppression of chronic hepatitis C following superinfection with hepatitis B virus. Liver Int 2007;27:722-6. 28. Genesca J, Jardi R, Buti M, et al. Hepatitis B virus replication in acute hepatitis B, acute hepatitis B virus-hepatitis delta virus coinfection and acute hepatitis delta superinfection. Hepatology 1987;7:569-72. 29. Njei B, Do A, Lim JK. Prevalence of hepatitis delta infection in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2012. Hepatology 2016;64:681-2. 30. Patel EU, Thio CL, Boon D, Thomas DL, Tobian AAR. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus infections in the United States, 2011-2016. Clin Infect Dis 2019 January 3 (Epub ahead of print). 31. Mahale P, Aka PV, Chen X, et al. Hepatitis D viremia among injection drug users in San Francisco. J Infect Dis 2018;217: 1902-6. n engl j med 380;20 nejm.org 32. Shin EC, Jeong SH. Natural history, clinical manifestations, and pathogenesis of hepatitis A. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2018;8(9):a031708. 33. Foster M, Ramachandran S, Myatt K, et al. Hepatitis A virus outbreaks associated with drug use and homelessness — California, Kentucky, Michigan, and Utah, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018; 67:1208-10. 34. Current hepatitis A outbreak. Boston: Public Health Commission, Massachusetts Department of Public Health, 2019 (https:// www.mass.gov/info-­details/current-­hepatitis -­a-­outbreak). 35. Fyfe B, Zaldana F, Liu C. The pathology of acute liver failure. Clin Liver Dis 2018;22:257-68. 36. Hughes SA, Wedemeyer H, Harrison PM. Hepatitis delta virus. Lancet 2011; 378:73-85. 37. Olivero A, Smedile A. Hepatitis delta virus diagnosis. Semin Liver Dis 2012;32: 220-7. 38. Kumar M, Satapathy S, Monga R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of lamivudine to treat acute hepatitis B. Hepatology 2007;45:97-101. 39. Valdiserri R, Khalsa J, Dan C, et al. Confronting the emerging epidemic of HCV infection among young injection drug users. Am J Public Health 2014;104: 816-21. 40. Cranston K, Alpren C, John B, et al. Notes from the field: HIV diagnoses among persons who inject drugs — Northeastern Massachusetts, 2015-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68: 253-4. 41. Dore GJ, Altice F, Litwin AH, et al. Elbasvir-grazoprevir to treat hepatitis C virus infection in persons receiving opioid agonist therapy: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2016;165:625-34. 42. Grebely J, Feld JJ, Wyles D, et al. Sofosbuvir-based direct-acting antiviral therapies for HCV in people receiving opioid substitution therapy: an analysis of phase 3 studies. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018; 5(2):ofy001. 43. Koh C, Heller T, Glenn JS. Pathogenesis of and new therapies for hepatitis D. Gastroenterology 2019;156(2):461-476.e1. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. May 16, 2019 The New England Journal of Medicine Downloaded from nejm.org at IDAHO STATE UNIVERSITY on July 16, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission. Copyright © 2019 Massachusetts Medical Society. All rights reserved. 1963