- Ninguna Categoria

Making of the Citizen: Equality & Inequality

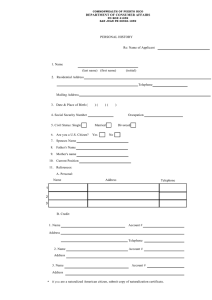

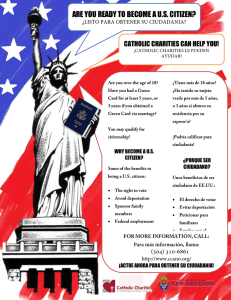

Anuncio