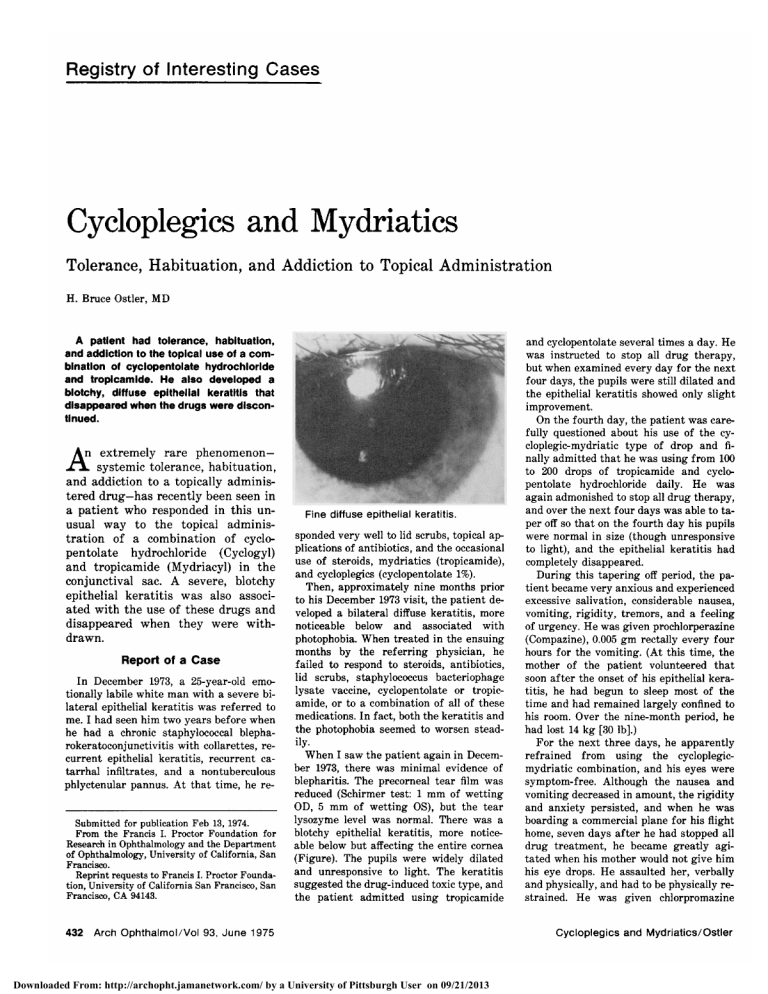

Cycloplegics Mydriatics and Tolerance, Habituation, and Addiction to Topical Administration H. Bruce Ostler, MD A patient had tolerance, habituation, and addiction to the topical use of a combination of cyclopentolate hydrochloride and tropicamide. He also developed a blotchy, diffuse epithelial keratitis that disappeared when the drugs were discontinued. An extremely rare phenomenon— systemic tolerance, habituation, and addiction to a topically adminis¬ tered drug—has recently been seen in a patient who responded in this un¬ usual way to the topical adminis¬ tration of a combination of cyclo¬ pentolate hydrochloride (Cyclogyl) and tropicamide (Mydriacyl) in the conjunctival sac. A severe, blotchy epithelial keratitis was also associ¬ ated with the use of these drugs and disappeared when they were with¬ .¿A. drawn. Report of a Case In December 1973, a 25-year-old emo¬ tionally labile white man with a severe bi¬ lateral epithelial keratitis was referred to I had seen him two years before when he had a chronic staphylococcal blepharokeratoconjunctivitis with collarettes, re¬ me. epithelial keratitis, recurrent catarrhal infiltrates, and a nontuberculous phlyctenular pannus. At that time, he recurrent Submitted for publication Feb 13, 1974. From the Francis I. Proctor Foundation for Research in Ophthalmology and the Department of Ophthalmology, University of California, San Francisco. Reprint requests to Francis I. Proctor Foundation, University of California San Francisco, San Francisco, CA 94143. cyclopentolate several times a day. He instructed to stop all drug therapy, but when examined every day for the next four days, the pupils were still dilated and the epithelial keratitis showed only slight improvement. On the fourth day, the patient was care¬ fully questioned about his use of the cycloplegic-mydriatic type of drop and fi¬ nally admitted that he was using from 100 to 200 drops of tropicamide and cyclo¬ pentolate hydrochloride daily. He was again admonished to stop all drug therapy, and over the next four days was able to ta¬ per off so that on the fourth day his pupils were normal in size (though unresponsive to light), and the epithelial keratitis had completely disappeared. During this tapering off period, the pa¬ tient became very anxious and experienced and was Fine diffuse epithelial keratitis. sponded very well to lid scrubs, topical ap¬ plications of antibiotics, and the occasional use of steroids, mydriatics (tropicamide), and cycloplegics (cyclopentolate 1%). Then, approximately nine months prior to his December 1973 visit, the patient de¬ veloped a bilateral diffuse keratitis, more noticeable below and associated with photophobia. When treated in the ensuing months by the referring physician, he failed to respond to steroids, antibiotics, lid scrubs, staphylococcus bacteriophage lysate vaccine, cyclopentolate or tropicamide, or to a combination of all of these medications. In fact, both the keratitis and the photophobia seemed to worsen stead- iiy. When I saw the patient again in Decem¬ ber 1973, there was minimal evidence of blepharitis. The precorneal tear film was reduced (Schirmer test: 1 mm of wetting OD, 5 mm of wetting OS), but the tear lysozyme level was normal. There was a blotchy epithelial keratitis, more notice¬ able below but affecting the entire cornea (Figure). The pupils were widely dilated and unresponsive to light. The keratitis suggested the drug-induced toxic type, and the patient admitted using tropicamide Downloaded From: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Pittsburgh User on 09/21/2013 excessive salivation, considerable nausea, vomiting, rigidity, tremors, and a feeling of urgency. He was given prochlorperazine (Compazine), 0.005 gm rectally every four hours for the vomiting. (At this time, the mother of the patient volunteered that soon after the onset of his epithelial kera¬ titis, he had begun to sleep most of the time and had remained largely confined to his room. Over the nine-month period, he had lost 14 kg [30 lb].) For the next three days, he apparently refrained from using the cycloplegicmydriatic combination, and his eyes were symptom-free. Although the nausea and vomiting decreased in amount, the rigidity and anxiety persisted, and when he was boarding a commercial plane for his flight home, seven days after he had stopped all drug treatment, he became greatly agi¬ tated when his mother would not give him his eye drops. He assaulted her, verbally and physically, and had to be physically re¬ strained. He was given chlorpromazine (Thorazine), hospitalized, and placed on "crisis observation." The following day, under medication with chlorpromazine, he was able to fly home without incident. Comment A limited degree of tolerance to the belladonna alkaloids has been ob¬ served in man,1 but since they can be absorbed directly from the conjuncti¬ val sac to only a limited extent, and since it is impossible to calculate the amount that can reach the nasal mu¬ cosa and gastrointestinal tract for absorption, an estimate of the total amount that can be absorbed is a matter of guesswork. We do know, however, that delirium and psychosis have occurred in children receiving only two drops of cyclopentolate hy¬ drochloride 2%2; and several adult patients of mine have complained of dryness of the mouth and a "strange, unreal feeling" after the instillation of cyclopentolate 2% for refractive purposes. However, the patient de¬ scribed in this report used more than 25 drops at a time of either tropic¬ amide 1%, cyclopentolate hydrochlo¬ ride 1%, or both, without side effects, suggesting that he had developed a considerable degree of tolerance. Although vomiting, malaise, sweat¬ ing, and excessive salivation have been noted in patients with Parkin¬ son disease when belladonna drugs have been suddenly withdrawn, habit¬ uation and addiction have not been thought to occur.1 Nevertheless, in our patient's case, withdrawal was ac¬ companied by increased anxiety, ex¬ cessive salivation, rigidity, tremors, and severe nausea and vomiting, all of which persisted for more than a week after the drugs had been with¬ drawn. This certainly suggested physical habituation. In addition, his compulsive use of the medications, with overdosing, profound psycholog- ical involvement, and the aggression shown by the attack on his mother in his effort to obtain the drops, all sug¬ gested true addiction. The patient had to be frequently reassured that he was responding to treatment as he should. His mother stated that at the onset of his eye problem, he began taking four drops every two hours instead of two drops every four hours as instructed. Then, when not relieved of the photophobia for which the medication had been prescribed, he gradually increased the dosage. The patient is an only child living dominant mother and an alcoholic father. His means of han¬ dling his anxiety and conflicts by pas¬ sive avoidance (as suggested by his withdrawal from society while on the medication), and his physical abuse of his mother only when his anxiety reached a high peak, suggest the be¬ havior of a narcotic addict3 rather than an alcoholic.4 The prognosis for cure of his addiction, and the pre¬ vention of other types of addiction, depend on whether both the patient and his parents take the psychia¬ trist's advice that each of them begin intensive individual psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. One can only speculate on the cause of the epithelial keratitis. Was it in¬ duced by the preservative (benzalkonium [Zephiran] chloride 1:10,000 in cyclopentolate or phenylmercuric ni¬ trate 0.002% in tropicamide), or by the drugs themselves—one or the other or in combination? The diminished tear¬ ing, as manifested by the drop in the Schirmer reading, interfered with normal dilution of the drugs when they were instilled into the eye, and this of course provided a higher than normal concentration of both the drug and the preservative to act on the epithelial surface. To this extent, at home with a mydriatic played at least a sec¬ ondary role in the production of the keratitis. It was interesting, however, that the tears that were produced contained the normal amount of lythe sozyme so that the modification was in quantity only and not in quality. Benzalkonium has been known to induce epithelial keratitis in dilutions of 1:3,500 and 1:1,000,5 but not in a di¬ lution of 1:10,000. Phenylmercuric ni¬ trate has apparently never been known to cause epithelial keratitis, but it must be borne in mind that in the case reported here, the amount of medication that reached the corneal epithelium daily What effect such was an astronomical. amount of either nitrate or ben¬ zalkonium could have on the epithe¬ lium can of course only be conjec¬ tured. phenylmercuric Key Words.—Tolerance; habituation; ad¬ diction; cycloplegics; mydriaties; epithelial keratitis; preservatives. Names and Trademarks of Drugs Nonproprietary Tropicamide-Mydriacyl. Chlorpromazine-CAfor-Pz, Cromedazine, Thorazine. References 1. Goodman LS, Gilman A: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. New York, Macmillan Co, 1965, p 530. 2. Binkhorst RD, et al: Psychotic reaction induced by cyclopentolate (Cyclogyl): Results of pilot study and a double-blind study. Am J Ophthalmol 55:1243-1245, 1963. 3. Zimmering P, et al: Drug addiction in relation to problem of adolescence. Am J Psychiatry 109:272-278, 1952. 4. Zwerling I, Rosenbaum M: Alcoholic addiction and personality (nonpsychotic condition), in Arieti S (ed): American Handbook of Psychiatry. New York, Basic Books Inc, Vol 1, 1951, pp 623\x=req-\ 644. 5. Swan KC: Reactivity of the ocular tissues to wetting agents. Am J Ophthalmol 27:1118-1122, 1944. Downloaded From: http://archopht.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of Pittsburgh User on 09/21/2013