1. Obladen M. Necrotizing enterocolitis -150 years of fruitless search for the cause. Neonatology.

Anuncio

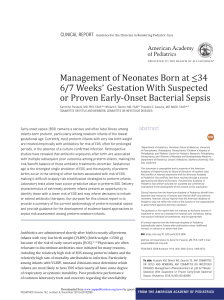

Sources of Neonatal Medicine Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 DOI: 10.1159/000215590 formerly Biology of the Neonate Received: January 12, 2009 Accepted after revision: January 22, 2009 Published online: April 29, 2009 Necrotizing Enterocolitis – 150 Years of Fruitless Search for the Cause Michael Obladen Department of Neonatology, Charité University Medicine, Berlin, Germany Abstract Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is not a new disease but one that has been reported since special care units began to house preterm infants. It was observed in foundling hospitals in Paris [Billard, 1828] and Vienna [Bednar, 1850] and, as it occurred in clusters, was regarded as a nosocomial infection in the infant hospitals of Zurich [Willi, 1944] and Berlin [Ylppö, 1931]. Clinical and patho-anatomic characterization was achieved by Schmidt and Quaiser in 1952. The unproven hypothesis of mesenteric hypoperfusion as a major etiological factor arose from animal models and analogous perforating disorders in term infants. Despite similarities between NEC and clostridial infections, few studies employed anaerobic culture techniques. The pathogenesis remains unclear and its distinction from related disorders uncertain. It is unlikely that strategies to prevent NEC will be successful unless the disease is better understood. Copyright © 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel © 2009 S. Karger AG, Basel 1661–7800/09/0964–0203$26.00/0 Fax +41 61 306 12 34 E-Mail [email protected] www.karger.com Accessible online at: www.karger.com/neo Introduction/Epidemiology Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an inflammatory disease of the gut with symptoms of abdominal distension, bilious vomiting, and bloody stools. It may proceed to septic shock, disseminated intravascular coagulation, peritonitis, and intestinal perforation. All parts of the gastrointestinal tracts may be involved, manifesting as multifocal hemorrhages, ulceration, and necroses. Almost exclusively a disorder of preterm infants, NEC was not recognized until special care units facilitated their survival. Presently, NEC has become the most common gastrointestinal emergency in neonates. This historic search focuses on the etiology and diagnosis of NEC in preterm infants and omits discussion of animal models as well as prevention and therapy. Early Reports Based on Postmortem Anatomy In 1823, the Paris Athénée de Médecine offered a scientific prize to ‘describe, following precise observations, the anatomic characteristics specific for inflammation of the gastrointestinal mucous membrane’ [1]. The prize was won by the 24-year-old intern Charles Billard for his book entitled ‘De la membrane muqueuse gastro-intestiProf. Dr. Michael Obladen Department of Neonatology, Charité University Medicine Augustenburger Platz 1 DE–13353 Berlin (Germany) Tel. +49 30 450 566 122, Fax +49 30 450 566 922, E-Mail [email protected] Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM Key Words Necrotizing enterocolitis ⴢ Etiology, necrotizing enterocolitis ⴢ History, necrotizing enterocolitis nale dans l’état sain et dans l’état inflammatoire’. At the Hôtel-Dieu of Angers he had not seen premature infants; the 81 observations in his 565-page book did not include neonatal NEC. But the prize, connected with membership to an academic society, allowed Billard to continue his medical training in Paris. He chose the Hôpital des Enfants Trouvés which, in 1826, admitted 5,392 foundlings [2], giving him ample opportunity for clinical and postmortem observations in neonates. His next book [3] described a neonatal disease which he termed ‘gangrenous enterocolitis’: ‘the mucosa of small and large intestines swollen, injected, in the colon often a large number of millet-sized dirty-dark red spots. ... In addition, the mucosa including the submucous tissue frequently corroded ... in many areas of the small intestine yellowgrey infiltrates with a tendency towards gangrene.’ ‘50th observation. Caroline Jossey, 9 days old, small and weak, is admitted to the ward for sick neonates on the 7th of November (1826). She shows generalized redness of the integuments and edematous extremities. The temperature of her skin is normal, her cry unaltered; her pulse irregular at a rate of 92/min. The infant has copious green-stained diarrhea. An intense perianal redness is noticed; the abdomen is swollen. On the 12th the green stool is mixed with streaks of blood. ... On the 14th the infant yields a large amount of blood with the stool; her face is thin, livid and entirely distorted; she vomits the administered liquids; her extremities are cold and livid, her belly is tense; the heartbeat extremely slow; finally she dies in the evening yielding a large quantity of black liquid blood through the anus. – When opening the body on the next morning ... the duodenum is in healthy state, the terminal ileum is intensely red and swollen, its mucosa friable and the surface covered with blood. When these fluids are removed, the membrane looks rough and bloody; its surface furrowed by numerous wrinkles between which there are deep and black lines with the aspect of being burned by nitric acid. In addition to these blackish furrows, there are a large number of spots or ecchymoses with the same appearance in different regions of the colon. On these spots the mucosa is so soft that it turns to mash when scraped with the fingernail ...’ Arvo Ylppö [6], later director of the Helsinki University Children’s Hospital, organized Germany’s first special care unit for preterm infants at the Berlin Kaiserin Auguste Victoria Haus from 1912 to 1920, and described NEC in 1931: ‘... a stomach gangrenous at its small curvature with a perforation the size of a silver penny, containing a green liquid which, as the large curvature was unharmed, had not leaked into the peritoneal cavity. Also the duodenum’s origin participated in the gangrenous metamorphosis. ... It deserves mention that both from the mother’s calculation and from the infant’s aspect the birth had occurred about 6 weeks too early.’ Among 597 neonates admitted to the Vienna hospital for foundlings from 1846 to 1847, its director, Alois Bednar [5], observed 25 infants with ‘entero-colitis’ of whom ‘8 were well nourished, 7 were premature and 10 were emaciated; 15 of them were between 3 and 10 days of age, 4 between 12 and 20 days, 5 between 22 and 30 days and 1 of 1 month and 22 days’. In 20 lethal cases, necropsy showed 204 Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 Systematic Observation in the First NICUs ‘The mucosal hemorrhages and ulcers in some cases lead to bean-shaped swellings in certain sections of the small intestine. These swellings originate from extensive necrosis of the intestinal wall which gives way to increased gas pressure within the gut. From these necrotic parts of the gut peritonitis easily arises, and therefore it is not at all rare that we find peritonitis with hemorrhagic or purulent exudation at postmortem examination of preterm infants. This is rarely diagnosed in vivo: It is so rapidly lethal that the clinical symptoms are unspecific (vomiting, meteoristic swelling of the abdomen without clear tension of the abdominal wall).’ In 1907, Switzerland’s first neonatal special care unit was founded – the Zurich Cantonal Infant Hospice Rosenberg. Heinrich Willi [7], its director since 1937, described 62 cases of ‘malignant’ enteritis occurring between 1941 and 1943: ‘The following case is characteristic: Sch., Anna Lilli (J.-Nr. 159/40), born June 10, 1940, birth weight 1,110 g, vital. On the 2nd day of life severe edema, spasmophilia, increasing icterus. On the 5th day asphyctic spell, recurring during the next day (heart malformation). At the beginning of July progressive pallor; stools become frequent, but did not raise concern as the infant nearly exclusively received wet nurses’ milk. On the July 8, vomiting; on the July 11, ballooned, tense abdomen, bilious vomiting, decay, finally fecal vomiting. Death on the July 12. Autopsy: Ulcerous and phlegmonous enteritis. Small intestine and coecum show numerous irregular round-oval defects with jagged and somewhat prominent margins, up to 8 mm in diameter. Enlarged mesenteric lymph glands. Fibrinous peritonitis. The heart shows hypoplasia of the tricuspid valve.’ Among Willi’s cases, 37 had a birth weight below 2,500 g; 12 were below 1,500 g. The disease occurred in clusters, as shown in figure 1c, and he assumed: ‘An indirect contact infection is most probable. ... Our prophylacObladen Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM Adam Elias von Siebold [4], director of the Obstetric Hospital of Berlin University since 1817, observed a preterm infant who had some but not all features of NEC: The critical scientist Bednar admitted: ‘If we refrain from pure speculation, we are without any knowledge of a specific cause’. Fig. 1. a Darmbrand in an adult and in an infant with jejunal perforation; from Hansen et al. [75]. b Localization of necrotic lesions in the cases of Schmidt and Quaiser [8, 9]. Black = Frequent; hatched = less frequent; x = rare. c Relation of occupancy in Willi’s ward and occurrence of ‘malignant’ enteritis [7]. White squares = Cases referred because of infection; hatched squares = in-house infection. tic measures had failed, due to the frequent overcrowding of our institution, which normally can provide for 44 infants.’ From 1948 to 1950, Kurt Schmidt [8] and Karl Quaiser [9] observed 85 mostly preterm infants in Graz, who died from a disease which they termed ‘enterocolitis ulcerosa necroticans’. All had been breast-fed: ‘Pathoanatomically it is an exceptionally characteristic enterocolitis predominantly in the ileocecum and the physiologic colon curvatures. It is frequently complicated by peritonitis due to transmigration or perforation. A specific pathogen could not be proven.’ The distribution of necrotic lesions is shown in figure 1b. Before the advent of modern neonatal intensive care, NEC remained rare, as did the survival of very immature infants. Schaffer’s 1965 issue of ‘Diseases of the Newborn’ did not mention it, and Beryl Corner, who in 1946 set up the preterm infants unit at Southmead Hospital in Bristol, emphasized [10]: ‘We never saw a case of NEC prior to 1967, and we know it did not exist, because of our very high postmortem rate and our very careful care of all babies. So we know it did not exist, and seemed to occur when we started fairly extensive catheterization, venous catheterization, for all sorts of different purposes.’ wide, affecting 7% of very-low-birth-weight infants in the US [11] and Canada [12] and killing approximately 500 infants per year in the US [13]. Diagnostic Criteria In 1899, Hahn [14] observed pneumatosis intestinalis during a laparotomy. In 1938, Botsford and Krakower [15] anatomically described it in 6 infants, among them a 4-week-old preterm infant. Ann Arbor radiologist Arthur Stiennon [16] saw pneumatosis on X-ray in 1951 and proposed: ‘From the mesenteric root gas can dissect, extend to the mesenteric insertion of the intestine and from here either dissect along the subserosal layers or, following the blood vessels ..., enter the submucosa.’ Pneumatosis portalis was described by Wolfe and Evans [17]; the whole spectrum of X-ray signs in NEC was characterized by Berdon et al. [18]. In 1978, Bell et al. [19] combined historical, clinical and radiographic data to define three stages, which were further subdivided by Walsh and Kliegman [20], whose classification gained widespread acceptance. Paracentesis and lavage were proposed by Kosloske and Lilly [21] to detect gangrene, peritonitis and perforation. History of Necrotizing Enterocolitis Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 205 Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM By the turn of the century, NEC had become the most important gastrointestinal emergency in infants world- Table 1. Clinical series on preterm infants since Willi, with major suggestions for the pathogenesis of NEC Proposed pathogenesis Year First author Site Cases n AC Ref. Nosocomial infection Air dissection at mesenteric root Endemic infection, probably virus 1944 1951 1952 Zurich Ann Arbor Graz, infants born 1948–1950 1953 1955 62 2 (85) 73 9 ? no no no Cluster within 53 days House endemy, viral Endemic, ischemia, Shwartzman reaction Noninfectious etiology, systemic hypoxemia Pseudomonas infection Reaction to endotoxin and deficient lysozyme; intestinal ischemia; injury + bacteria + feeds Willi Stiennon Schmidt, Quaiser Refinetti Köttgen no no [7] [16] [8] [9] [23] [24] 1959 1961 1963 1964 1965 1967 1975 1969 1969 1969 1970 1971 1971 1972 1974 1975 1975 1976 1976 1977 1978 1978 1981 1982 Rossier Singleton Waldhausen Berdon Mizrahi Touloukian Santulli Wilson Lloyd Stevenson Hopkins Stevenson Bell Stein Virnig Frantz Book Siassi Volsted Pedersen Book Bell Kosloske Nagaraj Lawrence Paris Hérold Houston Indianapolis New York Babies, four reports, infants born since 1955 15 10 6 (21) (18) (25) 64 16 87 (21) (13) (38) 43 11 21 54 16 1 13 74 48 17 21 2 no t.n.s. no no t.n.s. no t.n.s. t.n.s. no no t.n.s. no no no t.n.s. no no no yes no yes yes no no [25] [26] [27] [18] [28] [29] [30] [31] [32] [33] [34] [35] [36] [37] [38] [39] [40] [41] [42] [43] [19] [44] [45] [46] Mesenteric ischemia, DIC Circulation like reflex in diving mammals Decreased mesenteric flow, umbilical/aortic catheters create spasm Salmonella cluster Endemic in summer, no agent found Formula feeding, DIC, umbilical artery catheter Hyperosmolar feeding Patent ductus arteriosus Gas-gangrene due to Clostridium perfringens Clustering: enteric transmissible agent Etiology, pathophysiology unclear: staging Clostridia infection in most severe cases Indomethacin Intestinal flora changed by antibiotics São Paulo Mainz Los Angeles Children’s Detroit Seattle, four reports, infants born since 1962 Johannesburg St. Paul Minneapolis Salt Lake City Los Angeles USC Copenhagen Salt Lake City St. Louis Children’s Albuquerque Louisville Brisbane AC = Anaerobic culture from blood or peritoneal fluid; no = no cultures reported; t.n.s. = technique not stated; DIC = disseminated intravascular coagulation. A frustrating aspect of NEC is the continuing lack of understanding of its etiology, despite thoughtful and well-designed basic and clinical research for over a century. Clustering suggested nosocomial infection with a remarkable variation in incidence between hospitals [22]. An impressive list of etiologic proposals has been published, some of which are shown chronologically in table 1. The disease became widely known when it attacked New York Babies Hospital. A total of 64 neonates with NEC were observed from 1954 to 1974, prompting 10 206 Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 clinical papers from this institution. In addition to animal studies, they generated the hypothesis of mesenteric hypoperfusion as major pathogenetic factor [28]: ‘The noncontagious nature of the disease is evidenced by the lack of epidemics. ... All premature infants at Babies Hospital are fed cow’s milk formula.’ Santulli et al. [30] specified: ‘Indirect injury to the mucosa may result from selective circulatory ischemia. This is the most acceptable theory of pathogenesis. It is supported by our clinical and pathological data.’ Obladen Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM Putative Causes and Pathogenesis Asphyxial or hypoxic episode Selective circulatory ischemia of the gut wall Resuscitation Vascular congestion Increased capillary permeability and fragility Focal hemorrhage Focal necrosis, primarily mucosal Invasive bacterial proliferation Transmural inflammation Intestinal ileus and dilatation Medical Rx Recovery Related Disorders and Differential Diagnosis (1) NEC in term infants accounts for less than 10% of cases. The onset is earlier and more rapid than in preterm infants and predisposing disorders affecting the circulation are usually present. NEC in term infants has been linked to congenital heart disease and/or heart operation [48, 49], perinatal asphyxia, polycythemia [50], exchange transfusion [51–54], protracted diarrhea with dehydration, maternal cocaine abuse, and exposure to HIV or antiretroviral medication. (2) Appendicitis has long been feared as a rare severe disorder of preterm infants: Isaac Abt [55], pediatrician at Chicago Northwestern University, found 20 cases under 3 months of age published before 1917. Additional cases were reported by Wilson [56], Engstrom [57], Meyer [58], Walker [59], and Hardman and Bowerman [60]. It is likely that today this disease is perceived as NEC. (3) Focal intestinal perforation was proposed to be different from NEC by Aschner et al. [61]. Also a disease of immature infants, it does not present with pneumatosis and the localized perforation is surrounded by normal tissue. Its pathogenesis is unknown as is that of NEC [62]. In the peritoneal fluid at laparotomy, Coates et al. [63] found enterobacteriaceae more frequently in NEC than in focal intestinal perforation. (4) Meconium plug/fetal peritonitis: Several commentators on this disease, which is not specific for preterm infants, were falsely credited for the ‘first’ NEC description. Simpson [64] published 23 instances of fatal peritonitis which began in utero; 4 other cases were reported by Zillner [65] in 1884, and 5 more by the Prague pathologist History of Necrotizing Enterocolitis Perforation Transmural necrosis Operative Rx Sepsis, peritonitis Death Fig. 2. Pathogenesis of NEC as proposed by Touloukian et al. [47] in 1972. Arnold Paltauf [66] in 1888. Also in Anton Genersich’s [67] much cited case of 1891 the perforation of the terminal ileum had occurred long before birth, the intraperitoneal masses were calcified, organized and vascularized. In 1905, ileus due to thickened meconium was correctly related to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency by former blood group discoverer and later Nobel prize winner Karl Landsteiner [68] in Vienna. (5) Septicaemia with ileus: That neonatal sepsis may originate from the intestine was shown by Bonn obstetrician H. Cramer [69]. A pioneer in neonatology at Yale, Ethel Dunham showed that staphylococcal septicemia may lead to gastric perforation [70]. (6) Neonatal pseudomembranous colitis is a complication of antibiotic treatment resulting from disrupted bacterial flora, overgrowth of Clostridium difficile in the colon, and release of toxins leading to mucosal damage and inflammation [71]. The pathogen’s name alludes to painstaking culture techniques. (7) Darmbrand (fire bowel): In 1918, Rudolf Jaffé [72] described 7 cases of lethal necrotizing and ulcerizing inflammation of the small intestine he had seen in severely Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 207 Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM Most of the supposed pathogenetic factors featured in table 1 act during the first days of life; NEC, however, usually develops at 2 weeks of age and often catches by surprise infants who were postnatally stable and have left the intensive care unit when everyone believed the battle to be won. Monocausal explanations did not provide an accurate explanation of NEC’s pathogenesis, and most researchers took refuge in more or less complex multifactorial models, as shown in figure 2 [47]. Immaturity, formula feeding, bowel ischemia, diminished immune function, infection with enterotoxin-producing bacteria all played a role, but their interaction and sequence remained elusive. It is remarkable that despite NEC’s clinical similarity to clostridial infection, endemic occurrence, and different frequency among hospitals, only a few studies employed anaerobic culture techniques. undernourished Russian prisoners of war. Expulsed from his Berlin chair of pathology in 1933, the Jewish scientist Jaffé escaped the Holocaust by emigrating to Venezuela where he observed exactly the same necrotizing enteritis in cachectic natives in 1947 [73]. An epidemic of the same disease, termed ‘darmbrand’, was observed in northern Germany from 1946 to 1948, with 364 cases in Lübeck (among them 13 infants) and a high mortality [74–76]. It occurred in starved persons who had eaten a large meal. In 1948, Zeissler [77] found that darmbrand was due to Clostridium perfringens infection. (8) Pigbel (enteritis necroticans) is probably identical to darmbrand. It was published by Murrell et al. [78] to be the most frequent cause of death in children in the highlands of Papua New Guinea. Patchy enteral necrosis occurred after ritual pork feasts in protein-deprived persons who consumed sweet potatoes containing heat-stable trypsin inhibitors [79]. Given that the major source of defense against this toxin is adequate proteolysis in the gut, these children were specifically vulnerable to the toxins of C. perfringens contaminating the pork. The disease disappeared from New Guinea with -toxoid vaccination. Pigbel has been observed in many underdeveloped regions and rarely in developed countries among diabetics [80, 81] and vegetarians [82]. Volsted Pedersen [42] first called attention to the striking clinical, roentgenological, and morphological similarities between pigbel and NEC. Perspectives/Conclusions By 1978, most features of NEC had been described; however, despite extensive research no substantial progress has been made since then in understanding its pathogenesis. Surprisingly little effort has been made to distinguish NEC from other diseases and to elaborate its definition. Several related diseases are linked to enterotoxic clostridial infections, which were sometimes reported in NEC, but require anaerobic detection. NEC may be a pool of different disorders instead of a single entity. Although these disorders may lead to the same outcome, the underlying mechanisms vary greatly. It is unlikely that effective prevention will be established unless the disease is better understood. Acknowledgements The author thanks Karl-Heinz Leven, MD, PhD, Institut für Geschichte der Medizin, Freiburg, and Anneliese Rossak, Zentrum für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin, Freiburg, for giving him generous and guided access to their libraries; Gabi Völker, Department of Neonatology, Charité Berlin, for help with the artwork, and Sarah Lieber, National Institutes of Health, Washington, D.C., for language editing. References 208 6 Ylppö A: Pathologie der Frühgeborenen einschliesslich der ‘debilen’ und ‘lebensschwachen’ Kinder; in Pfaundler M, Schlossmann A (eds): Handbuch der Kinderheilkunde, ed 4. Berlin, Vogel, 1931, vol 1, p 598. 7 Willi H: Über eine bösartige Enteritis bei Säuglingen des ersten Trimenons. Ann Pediatr 1944;162:87–112. 8 Schmidt K: Über eine besonders schwer verlaufende Form von Enteritis beim Säugling, ‘Enterocolitis ulcerosa necroticans’. I. Pathologisch-anatomische Studien. Oesterr Z Kinderheilkd 1952;8:114–136. 9 Quaiser K: Über eine besonders schwer verlaufende Form von Enteritis beim Säugling, ‘Enterocolitis ulcerosa necroticans’. II. Klinische Studien. Oesterr Z Kinderheilkd 1952;8:136–152. 10 Christie DA, Tansey EM: Origins of neonatal intensive care in the UK; in: Wellcome Witnesses to Twentieth Century Medicine. London, Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2001, vol 9, p 24. Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 11 Guillet R, Stoll BJ, Cotten CM, Gantz M, McDonald S, Poole WK, Phelps DL: Association of H2-blocker therapy and higher incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 2006; 117:e137– e142. 12 Sankaran K, Puckett B, Lee DS, Seshia M, Boulton J, Qiu Z, Lee SK: Variations in incidence of necrotizing enterocolitis in Canadian neonatal intensive care units. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004; 39:366–372. 13 Holman RC, Stoll BJ, Clarke MJ, Glass RI: The epidemiology of necrotizing enterocolitis infant mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health 1997;87:2026–2031. 14 Hahn E: Über pneumatosis cystoides intestinorum hominis und einen durch Laparotomie behandelten Fall. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1899;25:657–660. 15 Botsford TW, Krakower C: Pneumatosis of the intestine in infancy. J Pediatr 1938; 18: 185–194. Obladen Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM 1 Billard CM: De la membrane muqueuse gastro-intestinale dans l’état sain et dans l’état inflammatoire ou recherches d’anatomie pathologique sur les divers aspects sains et morbides que peuvent présenter l’estomac et les intestins. Ouvrage couronné par l’Athénée de médecine de Paris. Paris, Gabon, 1825, p IX. 2 Dupoux A: Sur les pas de monsieur Vincent. Trois cents ans d’histoire parisienne de l’enfance abandonnée. Paris, Revue de l’assistance publique, 1958, Graph. A. 3 Billard CM: Traité des maladies des enfants nouveau-nés et à la mamelle. Paris, Baillière, 1928, Obs. 50. 4 Siebold AEv: Brand in der kleinen Curvatur des Magens eines atrophischen Kindes. J Geburtsh Frauenzimmer Kinderkrankh 1825; 5:3–4. 5 Bednar A: Die Krankheiten der Neugeborenen und Säuglinge vom clinischen und pathologisch-anatomischen Standpunkte bearbeitet. Wien, Gerold, 1850, pp 101–103. History of Necrotizing Enterocolitis 34 Hopkins GB, Gould VE, Stevenson JK, Oliver TK: Necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. A clinical and pathologic evaluation of autopsy material. Am J Dis Child 1970;120:229–232. 35 Stevenson JK , Oliver TK, Graham CB, Bell RS, Gould VE: Aggressive treatment of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg 1971;6:28–35. 36 Bell RS, Graham CB, Stevenson JK: Roentgenologic and clinical manifestations of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: experience with 43 cases. Am J Roentgenol 1971; 112: 123–134. 37 Stein H, Geck J, Solomon A, Schmaman A: Gastroenteritis with necrotizing enterocolitis in premature babies. Br Med J 1972;ii:616– 619. 38 Virnig NL, Reynolds JW: Epidemiological aspects of neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Am J Dis Child 1974;128:186–190. 39 Frantz ID 3rd, L’Heureux P, Engel R, Hunt CE: Necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr 1975; 86:259–263. 40 Book LS, Herbst JJ, Jung AL: Necrotizing enterocolitis in infants fed an elemental formula. J Pediatr 1975;87:602–605. 41 Siassi B, Blanco C: Patent ductus arteriosus. Pediatrics 1976;57:347–351. 42 Volsted Pedersen P, Hart Hansen F, Halveg AB, Christiansen ED, Justesen T, Hogh P: Necrotizing enterocolitis of the newborn – is it gas-gangrene of the bowel? Lancet 1976; 398:715–716. 43 Book LS, Overall JC, Herbst JJ, Britt MR, Epstein B, Jung AL: Clustering of necrotizing enterocolitis. Interruption by infection-control measures. N Engl J Med 1977; 297: 984– 986. 44 Kosloske AM, Ulrich JA, Hoffman H: Fulminant necrotising enterocolitis associated with clostridia. Lancet 1978;312:1014–1016. 45 Nagaraj HS, Sandhu AS, Cook LN, Buchino JJ, Groff DB: Gastrointestinal perforation following indomethacin therapy in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr Surg 1981; 16: 1003–1007. 46 Lawrence G, Bates J, Gaul A: Pathogenesis of neonatal necrotising enterocolitis. Lancet 1982;i:137–139. 47 Touloukian R, Posch J, Spencer R: The pathogenesis of ischemic gastroenterocolitis of the neonate: selective gut mucosal ischemia in asphyxiated neonatal piglets. J Pediatr Surg 1972;7:194–205. 48 Downing DF, Grotzinger PJ, Weller RW: Coarctation of the aorta; the syndrome of necrotizing arteritis of the small intestine following surgical therapy. AMA J Dis Child 1958;96:711–719. 49 Polin RA, Pollack PF, Barlow B, Wigger HJ, Slovis TL, Santulli TV, Heird WC: Necrotizing enterocolitis in term infants. J Pediatr 1976;89:460–462. 50 Gunn T, Outerbridge E: Polycythemia as a cause of necrotizing enterocolitis. Can Med Assoc J 1977;117:438. 51 Orme RLE, Eades SM: Perforation of the bowel in the newborn as a complication of exchange transfusion. Br Med J 1968;iv:349– 351. 52 Corkery JJ, Dubowitz, Lister J, Moosa A: Colonic perforation after exchange transfusion. Br Med J 1968;iv:345–349. 53 De Sa DJ, Mucklow ES, Gough MH: Neonatal gut infarction. J Pediatr Surg 1970;5:454– 459. 54 Friedman AB, Abellera RM, Lidsky I, Lubert M: Perforation of the colon after exchange transfusion in the newborn. N Engl J Med 1970;282:796–797. 55 Abt IA: Acute appendicitis in infancy. Arch Pediatr 1917;34:641. 56 Wilson WE: Appendicitis in the newborn. Proc R Soc Med 1945;38:186–187. 57 Engstrom CQ: Acute appendicitis in a premature infant aged 3 weeks. Acta Paediatr 1949;37:355–358. 58 Meyer JF: Acute gangrenous appendicitis in a preterm infant. J Pediatr 1952;41:343–345. 59 Walker RH: Appendicitis in the newborn infant. J Pediatr 1957;51:429–434. 60 Hardman RP, Bowerman D: Appendicitis in the newborn. Am J Dis Child 1963; 105: 99– 101. 61 Aschner JL, Deluga KS, Metlay LA, Emmens RW, Hendricks-Munoz KD: Spontaneous focal gastrointestinal perforation in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 1988;113:364– 367. 62 Mintz AC, Applebaum H: Focal gastrointestinal perforations not associated with necrotizing enterocolitis in very low birth weight neonates. J Pediatr Surg 1993;28:857–860. 63 Coates EW, Karlowicz MG, Croitoru DP, Buescher ES: Distinctive distribution of pathogens associated with peritonitis in neonates with focal intestinal perforation compared with necrotizing enterocolitis. Pediatrics 2005;116:e241–e246. 64 Simpson J: Notices of cases of peritonitis in the foetus in utero. Edinburgh Med Surg J 1838;15:390–414. 65 Zillner E: Ruptura flexurae sigmoidis neonati inter partum. Virchows Arch Path Anat 1884;96:307–318. 66 Paltauf A: Die spontane Dickdarmruptur der Neugeborenen. Virchows Arch Path Anat 1888;111:461–474. 67 Genersich A: Bauchfellentzündung bei Neugeborenen in Folge von Perforation des Ileums. Virchows Arch Path Anat 1891; 126: 485–493. 68 Landsteiner K: Darmverschluss durch eingedicktes Meconium. Pankreatitis Centralbl Allg. Path Path Anat 1905; 16: 903– 907. 69 Cramer H: Gibt es vom Darm ausgehende septische septische Infektionen bei Neugeborenen? Arch Kinderheilk 1905; 42: 321– 327. Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 209 Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM 16 Stiennon OA: Pneumatosis intestinalis in the newborn. Am J Dis Child 1951; 81: 651– 663. 17 Wolfe JN, Evans WA: Gas in the portal vein of the liver in infants. Am J Roentgenol 1955; 74:486–489. 18 Berdon WE, Grossman H, Baker DH, Mizrahi A, Barlow O, Blanc WA: Necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. Radiology 1964;83:879–887. 19 Bell MJ, Ternberg JL, Feigin RD, Keating JP, Marshall R, Barton L, Brotherton T: Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. Therapeutic decisions based upon clinical staging. Ann Surg 1978;187:1–7. 20 Walsh MC, Kliegman RM: Necrotizing enterocolitis: treatment based on staging criteria. Pediatr Clin North Am 1986; 33: 179– 201. 21 Kosloske AM, Lilly JR: Paracentesis and lavage for diagnosis of intestinal gangrene in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis. J Pediatr Surg 1978;13:315–320. 22 Brown EG, Sweet AY: Neonatal Necrotizing Enterocolitis. New York, Grune & Stratton, 1980, p 14. 23 Refinetti P, De Carvalho Pinto VA, Morales R de V: Perfuracao intestinal em recém-nascidos prematuros. Pediatr Prat (São Paulo) 1953;24:219–230. 24 Köttgen N, Braun E, Wengler G: Endemische ulzeröse Enteritis bei Frühgeborenen. Mschr Kinderhk 1955;103:226–230. 25 Rossier A, Sarrut S, Delplanque J: L’enterocolite ulcéro-nécrotique du prématuré. Ann Pédiatr 1959;35:1428–1436. 26 Singleton EB, Rosenberg HM, Samper L: Radiologic considerations of the perinatal distress syndrome. Radiology 1961; 76: 200– 212. 27 Waldhausen JA, Herendeen T, King H: Necrotizing colitis of the newborn: common cause of perforation of the colon. Surgery 1963;54:365–372. 28 Mizrahi A, Barlow O, Berdon WE, Blanc WA, Silverman WA: Necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants. J Pediatr 1965; 66: 697–705. 29 Touloukian RJ, Berdon WE, Amoury RA, Santulli TV: Surgical experience with necrotizing enterocolitis in the infant. J Pediatr Surg 1967; 2:389–401. 30 Santulli TV, Schullinger JN, Heird WC, Gongaware RD, Wigger J, Barlow B, Blanc WA, Berdon WE: Acute necrotizing enterocolitis in infancy: a review of 64 cases. Pediatrics 1975;55:376–387. 31 Wilson SE, Woolley MM: Primary necrotizing enterocolitis in infants. Arch Surg 1969; 99:563–566. 32 Lloyd JR: The etiology of gastrointestinal perforations in the newborn. J Pediatr Surg 1969;4:77–84. 33 Stevenson JK, Graham CB, Oliver TK, Goldenberg VE: Neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: a report of 21 cases with fourteen survivors. Am J Surg 1969; 118:260–272. 210 75 Hansen K, Jeckeln E, Jochims J, Lezius A, Meyer-Burgdorf H, Schütz F: Darmbrand (enteritis necroticans). Stuttgart, Thieme, 1949, p 65, figs. 22, 46. 76 Fick KA, Wolken AP: Necrotic jejunitis. Lancet 1949;253:519–521. 77 Zeissler J: Zur Ätiologie der nekrotisierenden Enterocolitis. Med Klin 1948; 43: 341– 343. 78 Murrell TGC, Roth L, Egerton J, Samels J, Walker PD: Pig-bel: enteritis necroticans. A study in diagnosis and management. Lancet 1966;i:217–222. Neonatology 2009;96:203–210 79 Murrell TG, Walker PD: The pigbel story of Papua New Guinea. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1991;85: 119–122. 80 Severin WP, de la Fuente AA, Stringer MF: Clostridium perfringens type C causing necrotising enteritis. J Clin Pathol 1984; 37: 942–944. 81 Petrillo TM, Beck-Sague CM, Songer JG, Abramowsky C, Fortenberry JD, Meacham L, Dean AG, Lee H, Bueschel DM, Nesheim SR: Enteritis necroticans (pigbel) in a diabetic child. N Engl J Med 2000;342:1250–1253. 82 Farrant JM, Traill Z, Conlon C, Warren B, Mortensen N, Gleeson FV, Jewell DP: Pigbellike syndrome in a vegetarian in Oxford. Gut 1996;39:336–337. Obladen Downloaded by: Univ. of Michigan, Taubman Med.Lib. 141.213.236.110 - 8/4/2013 3:20:55 PM 70 Dunham EC, Shelton MT: Multiple ulcers of the stomach in a newborn infant with staphylococcus septicemia. J Pediatr 1934; 4: 39– 43. 71 Donta ST, Stuppy MS, Myers MG: Neonatal antibiotic-associated colitis. Am J Dis Child 1981;135:181–182. 72 Jaffé R: Über nekrotisierende und ulceröse Entzündungen im Dünndarm. Med Klin 1918;14:904–912. 73 Jaffé R: Über nekrotisierende und ulceröse Entzündungen im Dünndarm (sog. Darmbrand). Virchows Arch Path Anat 1950; 318: 23–31. 74 Jeckeln E: Über Darmbrand. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1947;72: 105–108.