00021 Mackintosh Types of Modern Theology

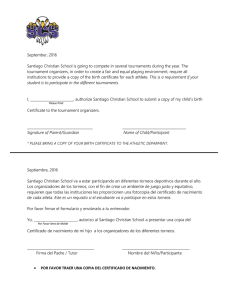

Anuncio