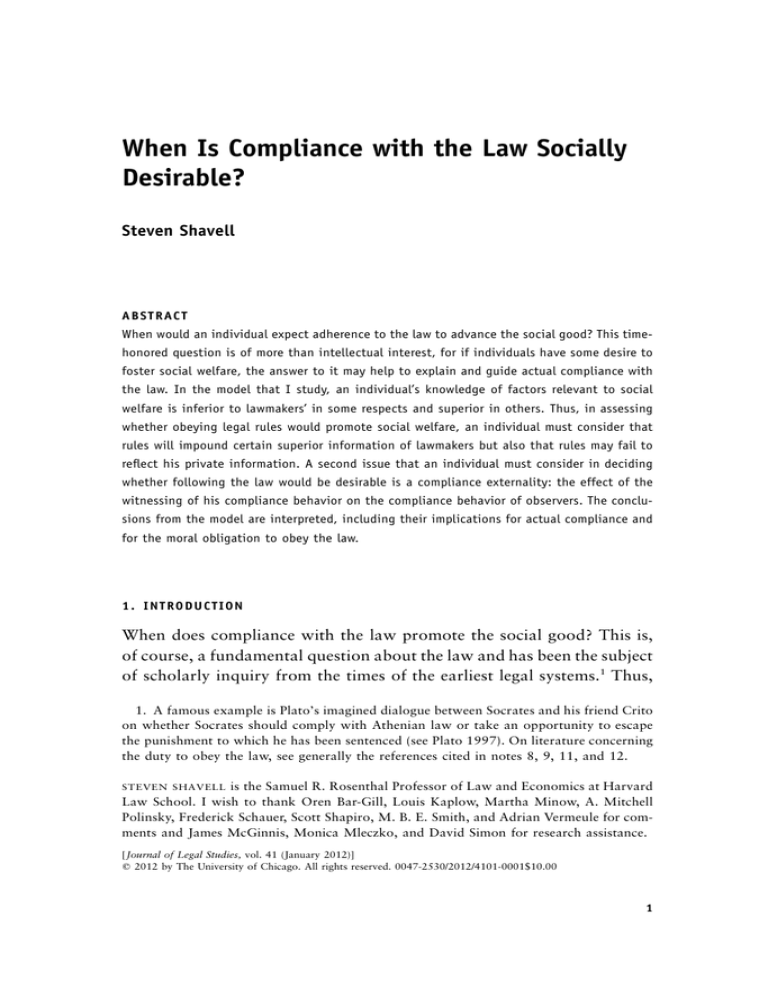

When Is Compliance with the Law Socially Desirable?

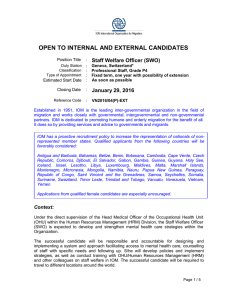

Anuncio