The Neolithic in the Iberian Peninsula

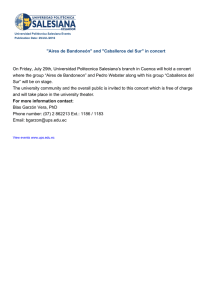

Anuncio