Document

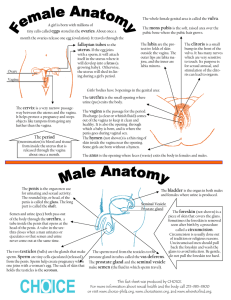

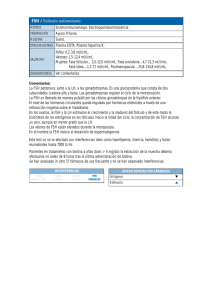

Anuncio

FEMALE GENITALIA Vulva The vulva, or pudendum, is a collective term for the external genital organs that are visible in the perineal area. The vulva consists of the following: the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, hymen, clitoris, vestibule, urethra, Skene's glands, Bartholin's glands, and vestibular bulbs. The boundaries of the vulva extend from the mons pubis anteriorly to the rectum posteriorly and from one lateral genitocrural fold to the other. The entire vulvar area is covered by keratinized, stratified squamous epithelium. The skin becomes thicker, more pigmented, and more keratinized as the distance from the vagina increases • Mons Pubis: is a rounded eminence that becomes hairy after puberty. It is directly anterior and superior to the symphysis pubis. The hair pattern, or escutcheon, of most women is triangular. • Labia Majora: are two large, longitudinal, cutaneous folds of adipose and fibrous tissue. Each labium majus is approximately 7 to 8 cm in length and 2 to 3 cm in width. The labia extend from the mons pubis anteriorly to become lost in the skin between the vagina and the anus in the area of the posterior fourchette. The skin of the outer convex surface of the labia majora is pigmented and covered with hair follicles. The thin skin of the inner surface does not have hair follicles but has many sebaceous glands. • Labia Minora: are two small, red cutaneous folds that are situated between the labia majora and the vaginal orifice. They are more delicate, shorter, and thinner than the labia majora. The skin of the labia minora is less cornified and has many sebaceous glands but no hair follicles or sweat glands. The labia minora and the breasts are the only areas of the body rich in sebaceous glands without hair follicles. Among women of reproductive age, there is considerable variation in the size of the labia minora. They are relatively more prominent in children and postmenopausal women. • Hymen: is a thin, usually perforated membrane at the entrance of the vagina. There are many variations in the structure and shape of the hymen. Small tags, or nodules, of firm fibrous material, termed carunculae myrtiformes, are the remnants of the hymen identified in adult females. • Clitoris: is a short, cylindrical, erectile organ at the superior portion of the vestibule. The normal adult glans clitoris has a width less than 1 cm, with an average length of 1.5 to 2 cm. • Vestibule: extends from the clitoris to the posterior fourchette. The orifices of the urethra and vagina and the ducts from Bartholin's glands open into the vestibule. Within the area of the vestibule are the remnants of the hymen and numerous small mucinous glands. • Urethra: is a membranous conduit for urine from the urinary bladder to the vestibule. The female urethra measures 3.5 to 5 cm in length. • Skene's Glands: or paraurethral glands, are branched, tubular glands that are adjacent to the distal urethra. • Bartholin's Glands: are vulvovaginal glands that are located beneath the fascia at about 4 and 8 o'clock, respectively, on the posterolateral aspect of the vaginal orifice. Each lobulated, racemose gland is about the size of a pea • Vestibular Bulbs: are two elongated masses of erectile tissue situated on either side of the vaginal orifice. Each bulb is immediately below the bulbocavernosus muscle. The vagina is a thin-walled, distensible, fibromuscular tube that extends from the vestibule of the vulva to the uterus. The potential space of the vagina is larger in the middle and upper thirds. The walls of the vagina are normally in apposition and flattened in the anteroposterior diameter. Thus the vagina has the appearance of the letter H in cross section. Cervix The lower, narrow portion of the uterus is the cervix. The word cervix originates from the Latin word for neck. The Greek word for neck is trachelos, and when the cervix is removed, the surgical procedure is termed trachelectomy. The cervix may vary in shape from cylindrical to conical. It consists of predominantly fibrous tissue in contrast to the primarily muscular corpus of the uterus. The vagina is attached obliquely around the middle of the cervix; this attachment divides the cervix into an upper, supravaginal portion and a lower segment in the vagina called the portio vaginalis The supravaginal segment is covered by peritoneum posteriorly and is surrounded by loose, fatty connective tissue, the parametrium, anteriorly and laterally. The canal of the cervix is fusiform, with the widest diameter in the middle. The length and width of the endocervical canal varies; it is usually 2.5 to 3 cm in length and 7 to 8 mm at its widest point. The width of the canal varies with the parity of the woman and changing hormonal levels. The cervical canal opens into the vagina at the external os of the cervix. In the majority of women the external os is in contact with the posterior vaginal wall. The external os is small and round in nulliparous women. The os is wider and gaping following vaginal delivery. Uterus The uterus is a thick-walled, hollow, muscular organ located centrally in the female pelvis. Adjacent to the uterus are the urinary bladder anteriorly, the rectum posteriorly, and the broad ligaments laterally The uterus is globular and slightly flattened anteriorly; it has the general configuration of an inverted pear. The short area of constriction in the lower uterine segment is termed the isthmus The dome-shaped top of the uterus is termed the fundus. The size and weight of the normal uterus depend on previous pregnancies and the hormonal status of the individual. The uterus of a mulliparous woman is approximately 8 cm long, 5 cm wide, and 2.5 cm thick and weighs 40 to 50 g. In contrast, in a multiparous woman, each measurement is approximately 1.2 cm larger, and normal uterine weight is 20 to 30 g heavier. The upper limit for weight of a normal uterus is 110 g. The capacity of the uterus to enlarge during pregnancy results in a 10- to 20-fold increase in weight at term. After menopause the uterus atrophies in both size and weight. Oviducts The paired uterine tubes, more commonly referred to as the fallopian tubes or oviducts, extend outward from the superolateral portion of the uterus and end by curling around the ovary . The uterine tubes connect the cornua of the uterine cavity and the peritoneal cavity. The ostia into the endometrial cavity are 1.5 mm in diameter, whereas the ostia into the abdominal cavity are approximately 3 mm in diameter. The oviducts are between 10 and 14 cm in length and slightly less than 1 cm in external diameter. Each tube is divided into four anatomic sections. The uterine intramural, or interstitial, segment is 1 to 2 cm in length and is surrounded by myometrium. The isthmic segment begins as the tube exits the uterus and is approximately 4 cm in length. This segment is narrow, 1 to 2 mm in inside diameter, and straight. The isthmic segment has the most highly developed musculature. The ampullary segment is 4 to 6 cm in length and approximately 6 mm in inside diameter. It is wider and more tortuous in its course than other segments. Fertilization normally occurs in the ampullary portion of the tube. The infundibulum is the distal trumpet-shaped portion of the oviduct. From 20 to 25 irregular fingerlike projections, termed fimbriae, surround the abdominal ostia of the tube. One of the largest fimbriae is attached to the ovary, the fimbria ovarica. Ovarios The paired ovaries are light gray, and each one is approximately the size and configuration of a large almond. The surface of the ovary of adult women is pitted and indented from previous ovulations. The ovaries contain approximately 1 to 2 million oocytes at birth. During a woman's reproductive lifetime, about 8000 follicles begin development. The growth of many follicles is blunted in various stages of development, however approximately 300 ova eventually are released. The size and position of the ovary depend on the woman's age and parity. During the reproductive years, ovaries weigh 3 to 6 g and measure approximately 1.5 cm × 2.5 cm × 4 cm. As the woman ages, the ovaries become smaller and firmer in consistency. El CICLO MENSTRUAL El ciclo normal de una mujer puede durar de 28 +-7días. Se separa en 2 fases que se siguen una de otra y depende de las hormonas que sean secretadas en cada mes, la recomendación es: tengan el ciclo, la imagen del retrocontrol y procedan a leer lo siguiente: I. Ciclo Ovárico Desarrollo Folicular: En la mujer, en el feto en formación, a partir de células germinales aparecen los oocitos, (ovogonia recubierta de epitelio superficial o célula pregranulosa) alrededor de la semana 20 existen unos 7000000 de oocitos, que han iniciado la meiosis y se detienen en profase I, para entrar en un periodo de latencia (diploteno), el cual culminará en la pubertad. Al momento del nacimiento, han sobrevivdo aproximadamente 2000000 de oocitos, y en la pubertad sólo quedan 400000. Los oocitos se mantienen en fase de diploteno, aparentemente por un Inhibidor de la Maduración del Oocito (OMI). En la pubertad, al darse una descarga rápida de LH (por el mecanismo de retroalimentación positiva al encontrarse bajo efectos estrogénicos) se reanuda la Meiosis I como se explicará a continuación. Para efectos de estudio se divide el ciclo en una fase folicular y una fase lútea. Fase folicular: los cambios en la variación del ciclo se deben a la duración de éste. •El Folículo Primordial: Al inicio de cada ciclo, unos 12 oocitos son reclutados e iniciados, ésta selección e inicio es independiente de FSH, sin embargo una vez iniciado, la maduración del folículo será dependiente de FSH. El reclutamiento está completo en el 2-5 día de ciclo menstrual. Se da un cecimiento del oocito, así como un desarrollo de las células foliculares, éstas últimas pasaran a formar un epitelio cúbico pseudoestratificado alrededor del oocito (cèlulas de la granulosa) y existe todavía una capa de células que lo recubren. La FSH es liberada principalmente porque al final de la fase lútea anterior ha disminuido la cantidad de progesterona e inhibina con lo que se estimula la secreción de FSH. •Folículo preantral (primario): Con el aumento de la FSH se da un desarrollo de las células de la granulosa, y éstas se apoyan en otras células foliculares que se han diferenciado en teca folicular. Éstas células de la teca van a producir un aumento en la concentración de estrógenos. Las células de la granulosa y el ovocito bajo la influencia de la FSH van a producir una glicoproteína que formará la zona pelúcida. La zona folicular se diferenciará en una teca interna y una externa. Solamente un folículo pasará a ser secundario y el resto experimentará atresia; se desconoce el mecanismo se selección. Existe una teoría de 2 células y 2 gonadotropas que dice lo siguiente: La LH estimula a las células de la teca para que éstas produzcan andrógenos, las células de la granulosa por medio de aromatización va a transformar los andrógenos en estrógenos, ésta aromatización es estimulada por la misma FSH. Los estrógenos en junto con la FSH provoca un aumento en la síntesis y expresión de receptores de FSH y proliferación de células de la granulosa. Los andrógenos a concentraciones bajas estimula la actividad aromatasa, mientras que a concentraciones altas, los andrógenos se transforman en andrógenos con diferente configuración que no se pueden aromatizar, éstos a su vez inhiben la expresión de receptores de FSH. Al mismo tiempo, aumentan las cantidades periféricas de estrógenos, que inhiben la liberación de GnRH y se ha liberado inhibina por parte del ovario. Entonces se tiene un microambiente adverso en el cual han disminuido la concentración de FSH así como receptores sus celulares, la FSH es necesaria para el desarrollo completo del folículo, por tanto sobrevivirá aquel folículo que tenga una mayor concentración estrogénica circundante así como la mayor cantidad de receptores para FSH. •Folículo de Graaf (secundario o preovulatorio): A medida q aumenta el desarrollo aparecen espacios ocupados por líquido (plasma y secreciones de las células granulosas) que al unirse forman el antro, es cuando se denomina folículo de Graaf. En éste punto, los estrógenos (producidos en la teca interna) han aumentado su concentración, lo cual disminuye la FSH y a la vez, pasadas unas 12 horas de descarga constante, van a tener un efecto de retroalimentación positiva sobre la LH con lo que sobreviene un pico de LH que va a tener efectos importantes: a. ovulación: al aumentar las prostaglandinas y enzimas proteolíticas permiten que el oocito salga a través de la membrana debilitada. b. se completa la meiosis I y se inicia la meiosis II. Aparece entonces el primer cuerpo polar; la fase de Meiosis II se completará si se da la fecundación. c. estimula la producción de progesterona por las células del estroma folicular lo que se denomina luteinización. •Fase Lútea: Es siempre constante, de 14 días. La corteza folicular restante se transforma en el cuerpo lúteo, productor de progesterona. Además se produce inhibina y estrógenos en cantidades importantes. Los cambios por retroalimetación negativa (disminución de FSH y LH) van a provocar la regresión del cuerpo lúteo (luteólisis) si no se da la fecundación, caen así los niveles de progesterona y estrógeno. Además existe una disminución de la inhibina. Se elimina la inhibición central de GnRH, FSH y de LH, iniciando así nuevamente el ciclo. Si se diera la fecundación será la gonadotropina coriónica humana placentaria limitará la acción de la LH y estimulará la secreción de progesterona por el cuerpo lúteo. II. Ciclo uterino y menstruación Cambios Cíclicos en el endometrio: El endometrio, a lo largo del ciclo bajo la influencia hormonal desarrollará cambios que teleológicamente le preparan para la implantación. Se habla de una fase proliferativa y una fase secretora, que coinciden con la fase folicular y la fase lútea respectivamente. Están determinados en gran parte por la concentración de estrógenos de origen folicular y la progesterona. •Fase proliferativa: Inicia con el día 1 del ciclo menstrual (primer día de la menstruación). Se da un crecimiento mitótico de la desidia funcional, así como la proliferación de glándulas endometriales que son cortas y rectas no tienen secreción alguna. La infiltración por neutrófilos comienza unos 2 días antes de la menstruación. Es entonces una restitución epitelial. •Fase secretoria: En el ciclo típico de 28 días la ovulación se produce en el día 14, en 48-72 horas, la secreción de estrógenos y principalmente de progesterona va a determinar los cambios. Se vuelve mucho más vascularizado y ligeramente edematoso, las glándulas más grandes empiezan a secretar un líquido claro. Es entonces una preparación para la implantación El endometrio que es irrigado por dos tipos de arterias los dos tercios superficiales que se desprenden durante la menstruación están irrigadas por arterias espirales largas y enrolladas. La capa profunda está irrigada por arterias basilares rectas y cortas. Al experimentar regresión el cuerpo lúteo se interrumpe del apoyo hormonal del endometrio Aparecen focos de necrosis de la mucosa y de los vasos que producen focos hemorragicos que confluyen y producen el flujo menstrual. Patterns of histologic changes throughout menstrual cycle. (Modified from Noyes RW, Hertig AT, and Rock J: Fertil Steril 1:3, 1950. Reproduced with permission of the publisher, The American Fertility Society.) Menstruation There has been relatively little research regarding the mechanism of menstruation since the classic studies of Markee and those of Bartelmez in the 1930s and 1940s. In Markee's study, endometria from rhesus monkeys were transplanted into the anterior chamber of the eye of the same animal from which the tissue was obtained. He observed that during the cycle the transplants underwent four periods of change: (1) the period of rest (just after menses), (2) the first period of growth, (3) the second period of growth (after ovulation, when the transplants doubled in size again), and (4) the period of regression (when menstruation occurred) (Figure 4-47) . Markee noted that as steroid levels fell several days before menstruation, there was regression in the size of the transplants, resulting in coiling of the spiral arteries and slowing of the blood flow within them. Subsequently, vasoconstriction of the coiled arteries occurred. About 4 to 24 hours after vasoconstriction began, the coiled arteries relaxed, blood escaped from them, and menstruation began. Only the spiral arteries that supply the upper two thirds of the endometrium became coiled and constricted. The straight arteries supplying the stratum basale did not constrict. After this sequence of events, the cells are reorganized in structure and participate in the new proliferative process as described earlier, and the same cells that previously formed the secretory endometrium also form the new proliferative endometrium. Thus menstruation in humans is probably a combination of superficial tissue shedding brought about by ischemia, increases in IL-8, lysis from hydrolytic enzymes from macrophages, and loss of cell-cell binding proteins followed by reorganization and regeneration of endometrial cells. Diagram of changes in normal human ovarian and endometrial cycles. (From Shaw ST Jr and Roche PC: Menstruation. In Finn CA, editor: Oxford reviews of reproduction and endocrinology, vol 2, London, 1980, Oxford University Press.) Stenchever, A; et al. Comprehensive Gynecology. 4ª Edición. 2001 Berek, Jonathan. Novak's Gynecology. 2003 http://www.msnbc.com/news/wld/graphics/menstrual_cycle_dw2.swf