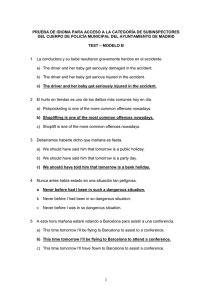

algunos aspectos de la vida cotidiana

Anuncio