¿Cómo influye la desorganización familiar en el consumo

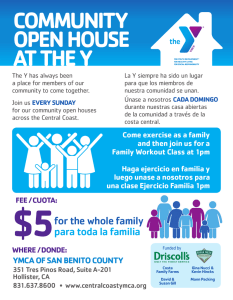

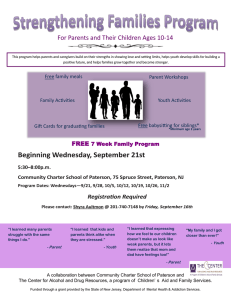

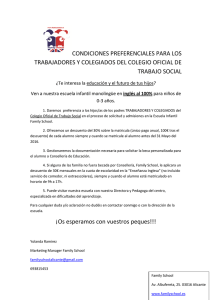

Anuncio