Violence within the couple

Anuncio

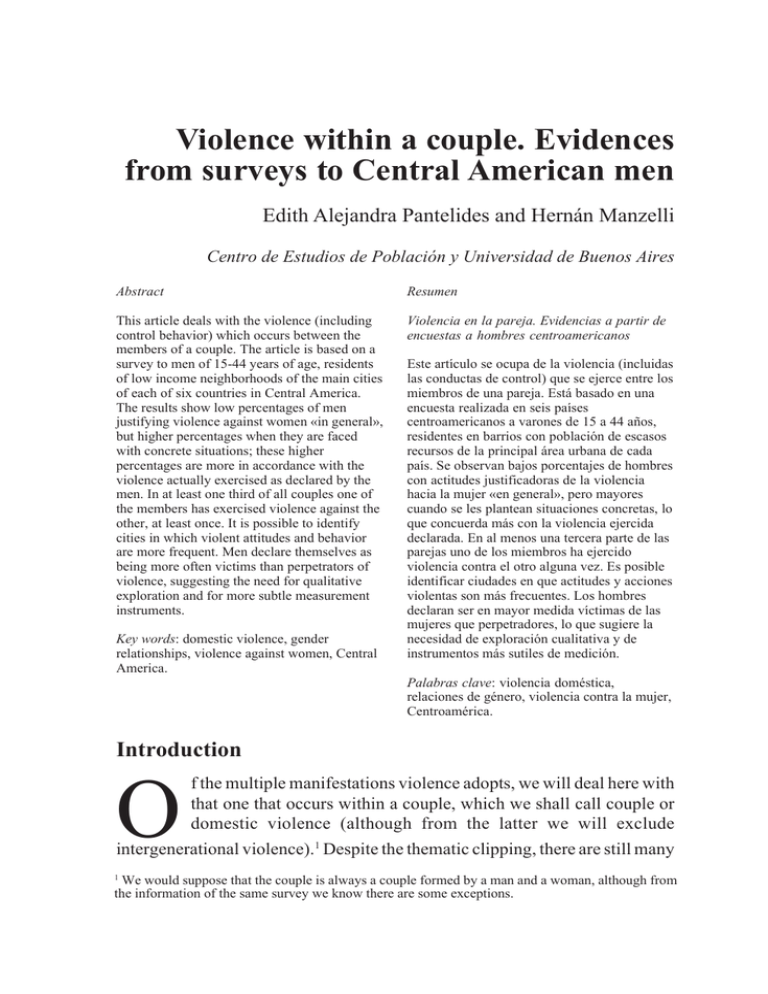

Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to Central American men Edith Alejandra Pantelides and Hernán Manzelli Centro de Estudios de Población y Universidad de Buenos Aires Abstract Resumen This article deals with the violence (including control behavior) which occurs between the members of a couple. The article is based on a survey to men of 15-44 years of age, residents of low income neighborhoods of the main cities of each of six countries in Central America. The results show low percentages of men justifying violence against women «in general», but higher percentages when they are faced with concrete situations; these higher percentages are more in accordance with the violence actually exercised as declared by the men. In at least one third of all couples one of the members has exercised violence against the other, at least once. It is possible to identify cities in which violent attitudes and behavior are more frequent. Men declare themselves as being more often victims than perpetrators of violence, suggesting the need for qualitative exploration and for more subtle measurement instruments. Violencia en la pareja. Evidencias a partir de encuestas a hombres centroamericanos Key words: domestic violence, gender relationships, violence against women, Central America. Este artículo se ocupa de la violencia (incluidas las conductas de control) que se ejerce entre los miembros de una pareja. Está basado en una encuesta realizada en seis países centroamericanos a varones de 15 a 44 años, residentes en barrios con población de escasos recursos de la principal área urbana de cada país. Se observan bajos porcentajes de hombres con actitudes justificadoras de la violencia hacia la mujer «en general», pero mayores cuando se les plantean situaciones concretas, lo que concuerda más con la violencia ejercida declarada. En al menos una tercera parte de las parejas uno de los miembros ha ejercido violencia contra el otro alguna vez. Es posible identificar ciudades en que actitudes y acciones violentas son más frecuentes. Los hombres declaran ser en mayor medida víctimas de las mujeres que perpetradores, lo que sugiere la necesidad de exploración cualitativa y de instrumentos más sutiles de medición. Palabras clave: violencia doméstica, relaciones de género, violencia contra la mujer, Centroamérica. Introduction f the multiple manifestations violence adopts, we will deal here with that one that occurs within a couple, which we shall call couple or domestic violence (although from the latter we will exclude intergenerational violence).1 Despite the thematic clipping, there are still many O 1 We would suppose that the couple is always a couple formed by a man and a woman, although from the information of the same survey we know there are some exceptions. Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM problems to be solved before approaching the analysis. A first observation is that there is not only one kind of violence within a couple. Leaving aside a simple classification based on the practiced violence severity, for example, Johnson (cited in Johnson and Ferraro, 2000: 949) establishes the following distinctions: “common violence within a couple”, “intimate terrorism”, “violent resistance” and “mutual violent control”. The common violence within a couple is the one that Is not connected to a general pattern of control [but that] emerges in the context of an specific quarrel when one or the two members attack each other. According to research led by Johnson, this kind of violence, which does not usually increase within time and is not severe and probable mutual, is the one that is mentioned in researches that use general population. Intimate terrorism is one of the tactics of a general pattern of control over the couple; it is usually one-sided, includes emotional abuse and may involve severe lesions. The control is maintained by the use of physical force and emotional pressure (Gerber, 1988, cited by Gonzalez Tapia (1991: 110)). Besides, “it should involve verbal and non-verbal behaviors (such as coercion and threats, intimidation, isolation, minimization, negation and guiltiness)” (Carcen, 1994, cited in Ramos, 1995). The violent resistance is practiced almost exclusively by women (the extreme example is the murder of the punisher partner) and the mutual violent control is given as a struggle for control between the members of the couple. Muehlenhard and Kimes are also worried for the definition of violence and show that, despite the concept seems simple, there is not a perfect methodological form of capture it and that different definitions reflect the interests of diverse groups of people. The authors mention that The definitions of terms such as sexual violence or domestic violence have the power of labeling negatively some acts, whereas some others are ignored and, implicitly, forgiven. The ways those terms are defined affects how people label, explain, assess and assimilate their own [experience] (Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1999: 234-235). For example, if the definition of violence is limited to those acts that involve physical force, all the emotional abuse and behaviors of control are excluded. If the definition is limited to the violence performed by men over women, other situations are skipped over: men against men, women against women and women against men. 232 / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli But also, as Muehlenhard and Kimes (1999: 237) mention, those who define what domestic violence is (legislators, social scientists, perpetrators, and victims) present implications for the inclusion or exclusion of certain behaviors as violent behaviors. The domestic violence issue has produced a debate over what Connell (1997: 1) calls “the gender balance of violence”2 There is plenty evidence that shows that domestic violence is performed by men (husbands, partners) against women more often than on the other way around (Dobash, Dobash and Wilson, 1992, cited in Connell, 1997). However, there are also studies that show that women accept having performed physical violence as frequent or more than what men mention (Currie 1998, cited in Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1999: 240) This apparently contradictory evidence shows the conceptual and methodological difficulties research in the subject faces, from both a theoretical (what is it understood by violence?) as well as methodological (how to measure violence?, who defines what is violence?, who informs on violence happenings? (Alksins et al., 2000; Johnson and Ferraro, 2000; Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1999). Violence within the couple and reproductive health Most of the researches that relate the issue of violence with the sexual and reproductive health do it through the consequences the exercise of the former over the latter. These consequences can be direct effect of a physical aggression, of a forced sexual intercourse or the restrictions imposed by the women’s autonomy which stops her from taking decisions over her own body. The most cited are the sexual transmitting illnesses, gynecological disorders (for example; pelvis inflammatory disorders), unwanted pregnancy, extreme sexual behavior (unprotected sex) and maternal mortality (Bott and Jejeebhoy, 2003; Ellsberg, 2003, Heise, Moore y Toubia, 1995a y 1995b; Population Council, 2004; Population Reports, 1999, Saucedo González, 1995; Unicef, 2000). Some studies have show, for example, that an important proportion of women are victims of violence during their pregnancy, with health consequences for her and the product (Ramirez and Vargas, 1998) and that he prevalence of violence does not change significantly during pregnancy, although the severity of emotional violence increases in detriment of the physical abuse (Castro and 2 The translations are ours despite marked otherwise. 233 july/september 2005 Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM Ruiz, 2004), on the other hand, there is a kind of violence within a couple that is per ser sexual: rape within marriage or courtships (date rape). Methodological Aspects Most of the researches that have addressed the gender violence subject, have asked women about their experiences as victims (Alksnis et al., 2000; Pantelides and Geldstein, 1999; Moore, 2003; Ramírez and Vargas, 1998; Suárez and Menkes, 2004). Researches that include men within their analysis universe, can be classified as: a) those who process men as gender violence perpetrators (Murray y Henjum, 1993; Reilly et al., 1992; Senn et al., 2000); b) those comparative researches between men and women as perpetrators and victims, (Bott and Jejeebhoy, 2003; Cáceres, 2000; Ellsberg, 2003; Forbes and Adams, 2001; Halpern and col., 2001; Haworth, 1998; O´Sullivan et al.,1998; Patel et al., 2003; Rosenthal, 1997; Rotundo et al., 2001; Zimmerman et al., 1995); and c) the researchers that analyze the exposition of men to violence experiences and the meaning that these events have for them (Fiebert, 2000; O’Sullivan y Byers,1993; Struckman et al., 1994). In the research this work is based on, a sample of men from 15 to 44 years of age, dwellers of low income neighbors was surveyed randomly in the cities3 of Belize, San Jose (Costa Rica), San Salvador (El Salvador), Tegucigalpa (Honduras), Managua, Bluefields and Puerto Cabezas (Nicaragua) and Panama. The sampling sizes were of 384 in Belize, 401 in Costa Rica, 291 in El Salvador, 400 in Honduras, 600 in Nicaragua and 463 in Panama. While the questions relative to attitudes toward violence were asked to all interviewees, the ones related to violent behaviors were asked to those who had had or currently had a couple, being this within a marriage, consensual union or courtship. It was not taken for granted that violence was performed only by men, but obviously, hey were the ones who informed about their violent behaviors as well as their partner’ behavior. There was not asked a general question about violence but the interviewees were asked to mention the frequency of certain behaviors (punches, slaps, kicks, pushes, jerks) from their partners to them and 3 Although for the general reader’s comfort, in the text we used the names of the countries and not the specific localities were the surveys were performed, it must be clear that the findings of this research can only be generalized to the population where the samples were taken and perhaps to other similar localities of the same countries. 234 / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli vice versa. Also the control behaviors that do not involve physical force were researched. However, lacking of the research was that a definition of violence or a classification of the types of violence that were intended to detect was not proposed a priori, reason why the opportunity of a more complete and systematic opportunity was lost. Attitudes toward violence In the first place we will analyze the attitudes toward violence from all the male interviewees. Despite in reality there is a “come and go” between behaviors and attitudes, through which both were modified within time, it seems logical that certain behavior presumes the existence of a supporting attitude (which motivates it and justifies it). However, behaviors and attitudes are not always coherent. The attitudes were measured by means of three propositions on which the interviewees had to manifest their agreement (total or partial) or their disagreement (Table 1). Less than 20 percent of the interviewees, in all the countries, justify violence under different circumstances, being the highest percentages in Belize, Nicaragua and Panama. However, within these percentages there are important variations between countries, this happens in relative terms. For example, the justification of violence against women in the case of infidelity gathers six times more adhesions in Belize than in Costa Rica; the percentage in Belize that justifies the opposed violence (women against men) is the double that the one in Costa Rica, El Salvador and Honduras; the percentage of those who think women should bear violence with the objective of having familiar unity in Nicaragua threefold those who think likewise in Costa Rica and Honduras. It is interesting to highlight that the percentage of those who justify the exercise of violence from women towards men in case of infidelity doubles, in almost all the countries, the percentage of those who justify the exercise of violence from men towards women under the same conditions. These answers are difficult to interpret since they seem to respond to an abstract condition that men do not hit women, which is modified, as we will shortly see, when “closer” questions are asked to the subjects. 235 july/september 2005 236 9.6 384 Women should bear the violence from the men in order to maintain a familiar unity N 3.7 491 7.5 2.0 * The answers «totally agree» and «partially agree» were added. 18.8 11.7 City of San José de Belice Costa Rica If the woman cheats on the man, he can beat her. If the man cheats on the woman she can beat him Situations of use of violence 7.6 291 8.2 4.1 San Salvador 3.8 400 8.3 2.3 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 13.3 600 13.8 7.8 Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas (Nicaragua) 6.0 463 15.1 8.4 City of Panamá TABLE 1 PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO JUSTIFY THE USE OF ACCEPTANCE OF VIOLENCE IN DIFFERENT SITUATIONS Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli The percentages mentioned so far are in general lower than those obtained when the proposals refer to physical aggression against their own couple (Table 2). The highest percentages according to the aggression in different situations were gathered in Belize and Nicaragua in all the researched items, whereas the lowest were generally in Honduras and Panama. In all the cities, physical aggression against the couple is mainly justified when she does not take proper care of the children (reaching the third part of the interviewees in the cities of Belize and Nicaragua), when she cheats on him and when she drinks or presents other vices (Table 2). But are much less those who justify when she visits her friend without permission or when she refuses to have sexual relations with her husband. In Belize the percentage of those who justify the violence if the woman dresses or behaves in a provocative manner is much higher; the same happens in Nicaragua concerning the aggression when the couple does not do the house work. Note that in many of the situations the aggression cause needs of a definition or delimitation: what is it understood by dressing or behaving in a “provocative manner”? Or by “do” the house work, or take “proper” care of the children? The opportunity for the discretion is large and facilitates the justification of violent acts. Also note that the questions about female infidelity (generic) and the cheating on the interviewee’s couple are comparable; however, the answers that manifest according the second proposal are several times higher to those that are done with the first. Perhaps is easier to disagree with the violence against “abstract” women than when it is about their own couple and when concrete causes are specified. It is also possible that the very statement by the interviewer of causes that would justify aggression would have produced a sensation of “permission” to recognize what under other circumstances would be difficult to declare. 237 july/september 2005 238 384 N * The answers «totally agree» and «partially agree» were added. 401 9.0 12.5 23.2 37.8 6.2 22.4 16.7 16.7 16.4 37.5 20.0 11.5 30.5 31.0 291 12.4 12.4 24.1 24.5 17.2 20.6 13.7 Ciudad de San José de Belice Costa Rica San Salvador She does not want to have sexual relations when her couple wants Ella traiciona a su pareja She visits her friends without permission She behaves or dresses provocatively She drinks or has another vices She does not do the house work She does not take good care of the children Physical agression from a man against his couple is justified 400 3.0 2.3 12.5 15.8 9.3 14.3 7.5 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 600 15.8 11.8 32.5 34.2 24.7 29.8 15.5 463 6.7 6.0 23.8 16.6 11.4 13.4 8.4 Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas Ciudad de (Nicaragua) Panamá TABLE 2 PRERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO JUSTIFY PHYSICAL AGGRESSION FROM MEN AGAINST THEIR COUPLES IN DIFFERENT SITUATIONS Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli Men as violence perpetrator In the first place let’s see the violent behaviors that this category of Johnson’s “intimate terrorism” comprises (Johnson and Ferraro, 2000). The exercise of control conducts and verbal violence by the interviewees against their couples appears more frequently in Belize and Nicaragua than in the other countries (Table 3). The most frequent control behavior among asked behaviors was the one that refers to whom the couple goes out with. In the cities of Nicaragua, for example, a third of the interviewees who had or have a couple declare having controlled, at least once, whom their couple went pout with, and only in Panama the frequency of this behavior descents under 20 percent. Among the verbal aggressions, insults appear to be the most common in all the countries. Take into account that the labeling of actions as insulting, threatening or humiliating depends, in this case, of the declarant perception, who is the real or potential aggressor, which leads us to think that the percentages of these and other kinds of aggressions we are analyzing underestimate the real frequency of this kind of behavior. In regards to the physical violence, again we find that Nicaragua and Belize present the lowest (Table 4). In all the countries the most frequent violent behavior is the pushing, followed by punching and slapping. It is not known if these relative frequencies reflect the real world or if it is easier to recognize those behaviors that appear as less violent among the violent. A summary measure that shows the percentage of those who once committed physical violence against their partners shows again that Nicaragua and Belize, in that order present the highest frequencies, and Honduras and El Salvador the lowest (inferior part of Table 4) In tables 5 and 6 the exercise of violence according educational level and age groups are shown. In the cases of Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Panama, the low educational level (incomplete elementary education) is associated to higher percentages of violence, but this relation is not observed in Honduras and Nicaragua. With the exception of Panama, where the highest percentages of men who declare having exercised violence against their partners are in the age group of 25 to 34 years of age, in all the other countries, this exercise is more frequent among older men. 239 july/september 2005 240 26.5 28.7 17.5 16.4 5.6 268 City of Belice 21.2 11.8 4.4 6.1 0.8 363 San José de Costa Rica 21.7 17.3 8.3 5.1 2.5 277 San Salvador 19.5 19.8 8.6 7.7 0.0 349 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) * The categories «frequently», «more than once but not frequently» and «once» were added. Controlling who she goes out with Insulting her Humiliating her Threatening her Others N Kinas of behavior 31.8 22.0 8.7 6.4 1.3 519 Managua, Bluefields y Pto Cabezas (Nicaragua) TABLE 3 PERCENTAGES OF INTERVIEWEES WHO EXERCISED VERBAL VIOLENCE ACTS AGAINST THEIR COUPLES 15.1 16.4 5.2 5.6 0.2 444 City of Panamá Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM 6.7 9.3 2.2 13.4 3.7 3.4 City of Belice 5.5 4.4 1.4 11.3 2.5 0.8 San José de Costa Rica 5.1 2.9 2.5 9.7 1.4 1.5 San Salvador 241 . ** For the construction of this variable all those interviewees who had at least once practices violence. * The categories «frequently», «more than once» and «once» were added. 12.3 349 5.2 3.4 2.6 8.6 2.6 0.3 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) Exercise of aggression of the interviewee against the couple (summary)** Exercised violence 21.6 16.8 12.6 N 268 363 277 Punch Slap Kick Push Jerk Other types of aggression Kinds of aggression 27.4 519 13.7 7.3 3.5 15.8 3.9 2.9 Managua, Bluefields y Pto Cabezas (Nicaragua) 16.9 444 5.4 9.0 2.9 10.1 2.5 0.5 City of Panamá TABLE 4 PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO PHYSICALLY ATTACKED THEIR COUPLE (MULTIPLE ANSWER) Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli / july/september 2005 11.2 363 22.1 268 10.8 277 20.0 12.4 San Salvador 15.6 349 10.9 10.8 * For the construction of this variable all those interviewees who had at least once practices violence. . 33.3 16.0 66.7 20.6 Incomplete elementary Incomplete secondary Complete secondary and further N San José de Costa Rica City of Belice Educative level of the interviewee 23.3 519 26.7 30.9 Managua, Bluefields y Tegucigalpa Pto. Cabezas (Honduras) (Nicaragua) 18.1 425 30.0 16.2 City of Panamá TABLE 5 PRECENTAGE OF INTERNVIEWEES OF EAH EDUCATIONAL LEVEL WHO EXERCISED VIOLENCE AGAINST THEIR COUPLES * Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM 242 . 20.3 18.1 30.8 268 City of Belice 13.9 15.2 21.8 363 San José de Costa Rica 5.9 14.3 20.5 277 San Salvador 4.3 16.1 19.8 349 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 27.2 23.9 31.5 519 For the construction of the violence exercise variable, all the interviewees that at least once had practiced it. 15-24 years 25-34 years 35-44 years N Interviewees’ age Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas (Nicaragua) 14.1 20.6 18.6 425 City of Panamá TABLE 6 PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES PF EACH AGE GROUP WHO EXERCISED VIOLENCE AGAINST THEIR COUPLES * Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli / 243 july/september 2005 244 City of Belice** 14.0 25.6 11.6 16.3 25.6 6.9 100.0 43 32.8 6.6 50.8 3.3 100.0 61 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 1.6 4.9 San José de San Costa Rica Salvador** 14.1 23.9 21.0 4.2 100.0 142 12.0 24.8 20.0 13.3 18.7 13.3 100.0 75 10.7 24.0 City of Panamá *In Panama was added to the category «does not know» some cases of interviewees who had to answer but the question was not made (equivalent to 10.7 percent). ** The data from Belize and El Salvador are not comparable with the data from other countries due to the high percentage of lack of answer, which also affects to a certain extent in Panama Desmoralization disrespect Jealousy Response to women’s aggression She was complaining Others N.S/N.R * Total N Reasons for the violence exercise Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas (Nicaragua) TABLE 7 DISTRIBUTION OF THE INTERVIEWEES WHO EXERCISED VIOLENCE AGAINST THEIR COUPLES ACCORDING TO THE REASON WHY THEY DID IT Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli The reasons why the interviewees justify having exercised violence against their couples (previous or current) are varied. In Tegucigalpa, the cities of Nicaragua and the city of Panama, jealousy seems to be the more mentioned category for physical violence, whereas in Costa Rica it would be an answer to women’s aggression. The “others” category is especially high in Costa Rica, El Salvador, and Honduras. We found gathered there the violence due to discussions and quarrels for different reasons (which in the case of Costa Rica is mentioned by 10 percent of the interviewees that exercised violence), as alcohol or drug consumption by him or due to problems with the children. The presence of haematomas was the most mentioned consequence of physical aggressions against women (26.4 percent in Nicaragua, 20.9 in Honduras, 20 in Panama, 15.5 in Belize, 14.8 in Costa Rica and 14.3 percent in El Salvador). Bruises only exceed the five percent in Panama and Nicaragua; whereas in El Salvador we found that 5.7 percent of the cases were burns. The declared cases of violence when the woman is pregnant were of 11.5 in Nicaragua, 9.32 in Honduras, 8.6 un El Salvador, 5.3 in Panama, 5.3 in Belize and 4.9 percent un Costa Rica, always over the total of interviewees that exercised any kind of violence against their couple. As we have already mentioned, and as Baumeister states (1996, cited in Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1999: 237) people resist to see themselves as violent people, the aforementioned percentages (always originated in the aggressors) would be an overestimation of violence’s real extension and severity. Men as violence victims As Valenzuela, among others, mention “…it is important to evaluate if the violence is performed unidirectionally from men against women or biderectionally between the two members of the couple…”, although “…taking into account that the lie, hiding, minimization and distortion of the facts constitute present characteristics in many of the men who exercise violence; and the power inequities that there still exist between men and women”. (Valenzuela, 2001: 161). 245 july/september 2005 246 24.3 519 7.9 11.8 2.1 14.3 6.0 3.1 24.1 444 7.0 8.6 1.8 12.2 0.9 4.7 City of Panamá * The categories «frequenlty», «more than once» and «once» were added. ** For the construction of this variable all the interviewees who had responded affirmatively were taken into account, although it was only to one of the violence types, at least once. 18.3 349 Exercise of violence by the couple against interviewee (summary)** Man victim of violence 28.4 19.6 14.1 N 268 363 277 8.5 11.0 1.7 13.5 2.8 2.2 6.6 9.7 1.7 9.7 4.3 1.7 15.7 15.3 8.2 16.8 7.1 4.9 City of Belice 4.7 5.4 1.8 8.3 2.2 2.9 Punch Slap Kick Push Jerk Other kina of aggression Types of aggression Managua, Bluefields y San José de Tegucigalpa Pto Cabeza Costa Rica San Salvador (Honduras) (Nicaragua) TABLE 8 PERCENTAGE OF COUPLES WHO EXERCISED EACH KIND OF PHYSICAL AGGRESSION AGAINST THE INTERVIEWEE Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli When comparing the prevalence of violence exercise by women against men (Table 8) with the prevalence of violence exercise of men against women (Table 4) always according of what was declared by men, it is observed that, with the exception of Nicaragua, in all the countries there is a higher percentage who declare having suffered from violence by their partners than those who declare having exercised violence against their partners.4 A hypothesis to interpret this finding is that feminine violence seems overestimated and male violence underestimated due to the already mentioned reasons. However, this interpretation does not take into account some constitutive elements of the hegemonic masculinity construction (Conell, 1995) according to which men should be the one in control and power of the situation, which would inhibit him to appear being the victim of a woman. Another hypothesis, which we consider of a stronger explanatory power and that shades this finding, states that when the violent situations are defined from the actors themselves, it is not always easy to establish who the victim is and who is the aggressor (Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1999: 237). The more common kind of violent behavior men are victims of is the pushing, the same that was mentioned when women were the victims of the physical aggressions from men (Table 8 and Table 6). Nonetheless, we found that in the case of the violence exercise by women there is a higher mention of violent behaviors that include slapping, punching and jerking. The cities where there is a stronger divergence among the declarations of violence exercised by women and that exercised by men are Panama (where the declaration of violence exercised by women exceed in seven percentage points the male violence), Belize (6.8 percentage points of difference) and Honduras (6.0 percentage points of difference). As we mentioned before, the only country where the percentage of citations of violence exercised by men exceeds the violence exercised by women is Nicaragua. However, in this case, the violent behavior percentages are the highest no matter who is the perpetrator, with a slight difference in favor of the violence exercised by men; this is of three percentage points. Tables 4 and 8). 4 It is worth saying that for some feminist thinkers a posture that contemplates that both men and women can be aggressors and victims of aggression would give a conservative thinking that maintains fundaments of the kind «if everybody is violent, there is no case we defend victimized women from domestic violence or rapes» (phrase cited in Muehlenhard and Kimes, 1998 to which the authors do no stick to). In this work we coincide with the feminist thinking that the violent risks are differential by gender (Morrison et al.,2004: 1), but we consider that the definition of violence would have to bear in mind the differential risks of women and people who are not generically identified from their biological sex, in participating or being victim of violent behaviors based on their sexuality, but not forgetting the violence exercised against men. 247 july/september 2005 Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM Violence environment and bidirectional violence In order to try to reflect in a more complex way the situations when violence within a couple is produced, we devised an indicator which we denominated “violence environment” calculated as the sum of the physical violence behaviors when women are the perpetrators and the violent behaviors when men are the perpetrators (without doubling the ones that mention one kind or another of violence). This indicator shows the frequency when at least one of the members of the couple exercised any kind of violence, at least once. Note that violent episodes took place in between 22 and 37 percent of the couples when the male member was the interviewee (Table 9) The cities that register higher violence percentages in any sense are the same that appeared when the exercise by men was analyzed: Belize and Nicaragua. In Belize, Costa Rica and Panama are among the highest frequencies of violent environments at the low education level (to incomplete elementary studies) whereas El Salvador and Nicaragua the highest percentages are in the medium levels (to incomplete secondary education) (Table 9). The city of Honduras is the only place where there is a higher percentage of violent environment among men of higher education level (complete secondary education and higher). When previously the exercise of violence according to the male perpetrator’s age was analyzed (Table 6) it was found that in almost all the countries the highest percentages of exercise of violence took place in the group of more age. In the case of men, who are in violent environments (Table 10) the situation is different, since in Costa Rica and El Salvador the frequency of violent environments increases as the interviewees’ age increases, whereas in the other countries there is no clear relation between the violent environment and the age. To conclude, let’s observe to what extent - always according to men’s declaration - there is two-way violence. Estimating the square chi it is observed that when there is one-way violence, there is also on the other way; in all the countries (p= 0.000) The possible interpretations of this evidence are three: a) that, indeed violence is frequently mutual; b) that men perceive an non-existent violence against them which they use (at an unconscious level) as a justification of their own violence, or c) that in their declarations men lie on purpose to justify their violence. We prefer a combination of the first two interpretations, despite the fact that surely there are cases in which the third apply. 248 249 22.5 25.3 363 268 24.5 38.9 36.8 36.9 36.8 66.7 City of San José de Belice Costa Rica 277 19.4 22.0 25.8 22.5 San Salvador 349 25.7 22.6 21.6 19.6 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 519 30.0 35.8 40.6 36.7 425 27.8 28.0 27.5 40.0 City of Panamá * For the construction of this variable were taken into account all the interviewees who had participated in at least one of the violence types (whoever the perpetrator was), at least in one occasion. . Complete elementary, incomplete secondary Complete secondary and further Total violence environment N Incomplete elementary Interviewees’ educative level Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas (Nicaragua) TABLE 9 PRECENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO DECLARED VIOLENCE ENVIRONMENT BY EDUCATIVE LEVEL Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli / july/september 2005 35.3 38.6 38.5 36.9 268 20.4 24.0 33.7 25.3 363 City of San José de Belice Costa Rica 16.8 20.0 30.7 22.0 277 San Salvador 12.9 29.7 28.6 22.6 349 Tegucigalpa (Honduras) 35.0 34.6 38.5 35.8 519 27.6 29.4 26.5 28.0 425 City of Panamá * For the construction of this variable were taken into account all the interviewees who had participated in at least one of the violence types (whoever the perpetrator was), at least in one occasion. 15-24 years 25-34 years 35-44 years Total violence environment N Age groups Managua, Bluefields y Pto. Cabezas (Nicaragua) TABLE 10 PERCENTAGE OF INTERVIEWEES WHO ARE WITHIN VIOLENT ENVIROMENTS BY AGE GROUPS Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM 250 / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli Conclusions To sum up, the low percentages of violence against women justifying attitudes “in general” do not fully demonstrate the degree of violence acceptance when the questions are about the interviewees’ couples and the specific reasons that, for them, would be justifying. Also, they do not show the predisposition of the interviewed men to exercise it. Indeed, it is in the questions that put the interviewees in concrete situations where there are more frequencies of permissive attitudes to violence against women, which are in agreement with the violent behaviors later declared. The highest percentages of violence exercise (both when the man is the perpetrator as well as when the woman is the perpetrator) were found in Belize and Nicaragua. The educational level seems to play an important role only in some of the countries (Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador and Panama), whereas age seems positively associated to the violence exercise in almost all the countries. The concept of violence environment in the couple allows having a clearer view of violent situations, further of who is the perpetrator and who is the victim, still taking into account that most of the cases women are the victims. The percentage of affected couples is between more than a fifth part to something more than a third. We also found that interviewed men declare more often to be victims of their partners than being them the perpetrators. These findings point the need of continuing the research on this subject, looking for better forms of gathering information and using qualitative instruments to try to understand this kind of findings. Bibliography ALKSINS, Ch., S. Desmarais, Ch. Senn y N. Hunter, 2000, “Methodological concerns regarding estimates of physical violence in sexual coercion: overstatement or understatement”, in Archives of Sexual Behavior, 29 (4). BOTT, S. and S. Jejeebhoy, 2003, “Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in South Asia: an overview of findings from the 2000 Mumbai Conference”, in Progress in Reporductive Health, núm. 64. CÁCERES, C., 2000, La (re)configuración del universo sexual. Cultura(s) sexual(es) y salud sexual entre los jóvenes de Lima a vuelta de milenio, Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia/ Redess Jóvenes, Lima. 251 july/september 2005 Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM CASTRO, R. and A. Ruíz, 2004, “Prevalencia y severidad de la violencia contra mujeres embarazadas, México”, in Revista de Saúde Pública, 38 (1). CONNELL, R. W., 1995, Masculinities, Allen & Unwin, Sydney. CONNELL, R. W., 1997, Arms and the man. Using the new research on masculinity to understand violence and promote peace in the contemporary world, Work presented at the Meeting on Male Roles and Masculinities in the Perspective of a Culture of Peace, September, Unesco, Oslo. ELLSBERG, M., 2003, Corced sex among adolescents: recent findings from Latin America, work presented at the Consultive Meeting on Non-consensual Sexual Experiences of Young People in Developing Countries, September 22-25, New Delhi. FIEBERT, M., 2000, “References examining men as victims of women´s sexual coercion”, in Sexuality and Culture, 4 (3). FORBES, G. and L. Adams-Curtis, 2001, “Experiences with sexual coercion in college males and females —Role of family conflict, sexist attitudes, acceptance of rape myths, self—esteem, and big-five personality factors”, in Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 16 (9). GONZÁLEZ Tapia, N., 1991, “Violación doméstica al amparo del derecho. La agresión a la mujer por el cónyuge o conviviente” en M. del C. Feijoó (comp.), Mujer y sociedad en América Latina, Clacso, Buenos Aires. HALPERN, C., P. Bouvier, P. Jaffe, R. Mounoud, C. Pawlak, J. Laederach, H. Wicky y F. Astie, 2001, “ Partner violence among adolescents in opposite-sex romantic relationship: findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health”, in American Journal of Public Health, 91(10). HAWORTH Hoeppner, S., 1998, “What´s gender got to do with it: Perceptions of sexual coertion in a university community”, in Sex Roles, 38 (9-10). HEISE, L., K. Moore and N. Toubia, 1995a, Sexual coercion and reproductive health. A focus on research, Population Council, New York. HEISE, L., K. Moore and N. Toubia, 1995b, “Defining coercion and consent crossculturally”, in SIECUS Report, 24 (2). JOHNSON, M. P. and K. J. Ferraro, 2000, “Research on domestic violence in the 1990s: making distinctions”, in Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62. MOORE, A., 2003, Female control over first sexual intercourse in Brazil: case studies of Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais and Recife, Pernambuco, The University of Texas at Austin, doctoral thesis, Austin. MORRISON, A., M. Ellsberg y S. Bott, 2004, Addressing gender-based violence in the Latin American and Caribbean region: a critical review of interventions, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 3438, World Bank, en http://econ.worldbank.org . MUEHLENHARD, C. y L. Kimes, 1999, The social construction of violence: the case of sexual and domestic violence, in Personality and Social Psycholgy Review, 3 (3). MURRAY, J. y R. Henjum, R., 1993, “Analysis of sexual abuse in dating”, in Guiadance and Counselling, 8 (4). 252 / Violence within a couple. Evidences from surveys to... E. Pantelides & H. Manzelli O’SULLIVAN, L. and E. Byers, 1993, “Eroding stereotypes: college women’s attempts to influence reluctant male sexual partner”, en Journal of Sex Research, 30. O’SULLIVAN, L., E. Byers y L. Finkelman, 1998, “A comparison of male and female college students’ experiences of sexual coercion”, in Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22. PANTELIDES, E. and R. Geldstein, 1999, “Encantadas, convencidas o forzadas: iniciación sexual en adolescentes de bajos recursos”, en AEPA, CEDES, CENEP, Avances en investigación social en salud reproductiva y sexualidad, Buenos Aires. PATEL, V., G. Andrews, T. Pierre and N. Kamat, 2003, “Gender, sexual abuse and risk behaviours in adolescents: a cross-sectional survey in schools in Goa, India”, in Progress in Reproductive Health, 64. POPULATION COUNCIL, 2004, The adverse health and social outcomes of social coercion: experiences of young in developing countries, in www.popcouncil.org. POPULATION REPORTS, 1999, “Impact on women’s reproductive health”, en Population Reports, 27 (4). RAMÍREZ Rodríguez, J. and P. Vargas Becerra, 1998, “Una espada de doble filo: la salud reproductiva y la violencia doméstica contra la mujer”, en E. Bilac y M. Baltar da Rocha, Saúde reprodutiva na América Latina e no Caribe: temas e problemas, Editora 34, Rio de Janeiro. RAMOS Lira, L., M. Romero Mendoza and E Jiménez, 1995, “Violencia doméstica y maltrato emocional. Consideraciones sobre el daño psicológico”, in Salud Reproductiva y Sociedad, II (6-7). REILLY, M., B. Lott, D. Caldwell and L. DeLuca, 1992, “Tolerance for sexual harassment related to self-reported sexual victimization”, in Gender & Society, 6 (1). ROSENTHAL, D., 1997, “Understanding sexual coercion among young adolescents: communicative clarity, pressure, and acceptance”, in Archives of Sexual Behavior, 26 (5). ROTUNDO, M., D. Nguyen, y P. Sackett, 2001, “A meta-analytic review of gender differences in perceptions of sexual harassment”, in Journal of Applied Psychology, 86 (5). SAUCEDO González, I., 1995, “La relación violencia-salud reproductiva: un nuevo campo de investigación”, in Salud Reproductiva y Sociedad, II (6-7). SENN, C., S. Desmarais, N. Verberg y E. Wood, E., 2000, “Predicting coercive sexual behavior across the lifespan in a random sample of Canadian men”, in Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 17 (1). STRUCKMAN Johnson, C. and D. Struckman-Johnson, 1994, “Men pressured and forced into sexual experience”, in Archives of Sexual Behavior, 23 (1). SUÁREZ, L. and C. Menkes, 2004, La percepción de los estudiantes adolescentes de la violencia familiar. El caso de Chiapas y San Luis Potosí, México, trabajo presentado en la XXV International Congress of the Latin American Studies Association, October 7-9, Las Vegas. 253 july/september 2005 Papeles de POBLACIÓN No. 45 CIEAP/UAEM UNICEF, 2000, La violencia doméstica contra mujeres y niñas, UNICEF. Florence. VALENZUELA, V., 2001, “Hombres que viven relaciones de violencia conyugal”, in J. Olavarría, Hombres: identidad/es y violencia, Flacso, Red Masculinidad/es Chile y Universidad Academia de Humanismo Cristiano, Santiago de Chile. ZIMMERMAN, R., S. Sprecher, L. Langer, and C. Holloway, 1995, “Adolescents’ perceived ability to say ‘no’ to unwanted sex”, in Journal of Adolescence Research, 10 (3). 254