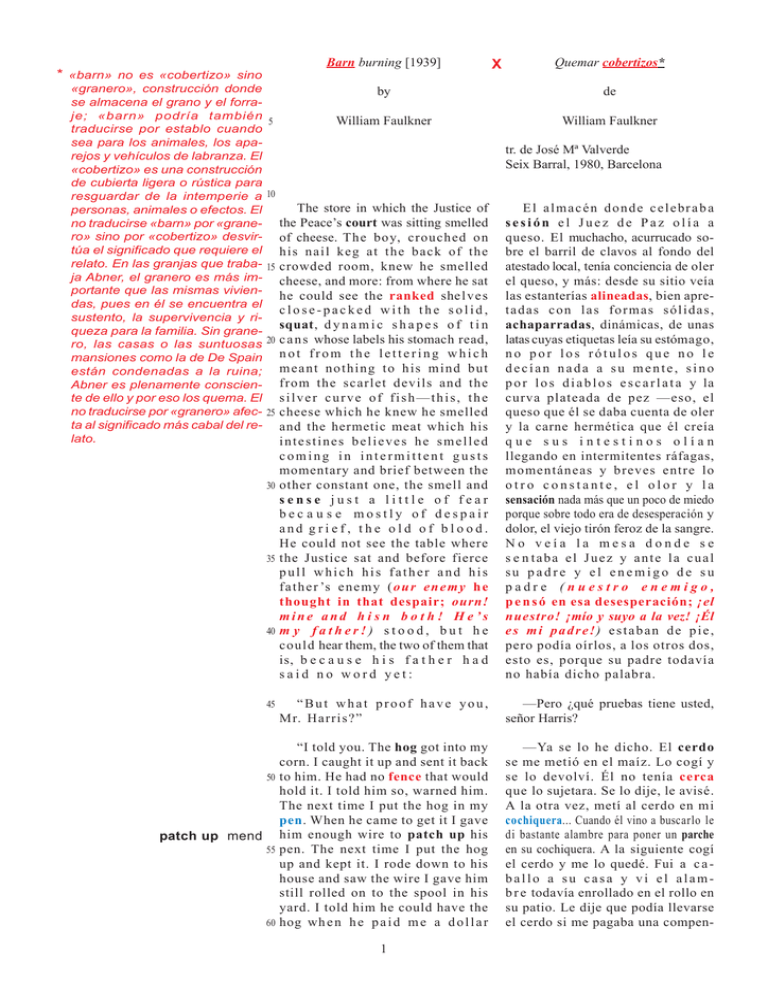

Faulkner, William Barn Burning-Notes-En-Sp.p65

Anuncio