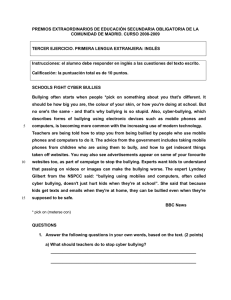

cyberbullying among young people - European Parliament

Anuncio