GRAN COCLÉ GRAN CHIRIQUÍ Lana S. Martin, Department of

Anuncio

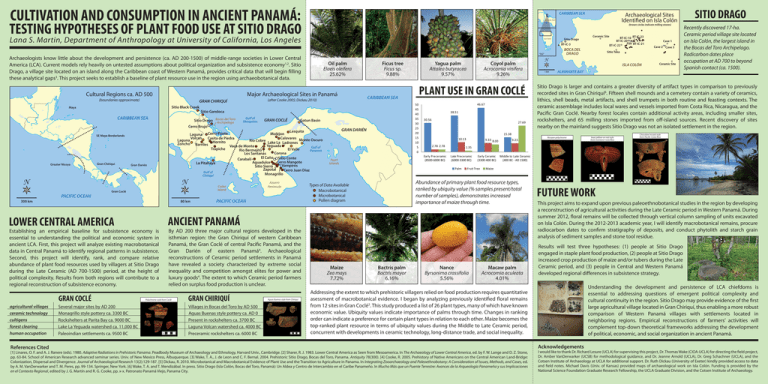

CULTIVATION AND CONSUMPTION IN ANCIENT PANAMÁ: CARIBBEAN SEA BOCAS DEL TORO TESTING HYPOTHESES OF PLANT FOOD USE AT SITIO DRAGO (brown circles indicate milling stones) Lana S. Martin, Department of Anthropology at University of California, Los Angeles ISLA COLÓN Oil palm Elaeis oleifera 25.62% Sitio Black Creek Maya CARIBBEAN SEA Gulf of Mosquitos GRAN COCLÉ Gatun Basin Cerro Brujo GRAN DARIÉN Lasquita Moléjon Laguna Cerro Punta Volcan Calavares Monte Oscuro Casita de Piedra Laguna Rio Cobre Hornito Lake La Ladrones Zoncho Barriles Yeguada Vaca de Monte Gulf of Trapiche El Valle Rio Bermejíto Panamá Corona Los Santanas El Caño Sitio Conte Carabalí Cerro Mangote Aguadulce La Pitahaya Vampiros Sitio Sierra Zapotal Cerro Juan Díaz Gulf of Monagrillo Chiriquí Greater Nicoya Gran Chiriquí Gran Darién N N PACIFIC OCEAN Gran Coclé 300 km 80 km By AD 200 three major cultural regions developed in the isthmian region: the Gran Chiriquí of western Caribbean Panamá, the Gran Coclé of central Pacific Panamá, and the Gran Darién of eastern Panamá4. Archaeological reconstructions of Ceramic period settlements in Panamá have revealed a society characterized by extreme social inequality and competition amongst elites for power and luxury goods4. The extent to which Ceramic period farmers relied on surplus food production is unclear. Establishing an empirical baseline for subsistence economy is essential to understanding the political and economic system in ancient LCA. First, this project will analyze existing macrobotanical data in Central Panamá to identify regional patterns in subsistence. Second, this project will identify, rank, and compare relative abundance of plant food resources used by villagers at Sitio Drago during the Late Ceramic (AD 700-1500) period, at the height of political complexity. Results from both regions will contribute to a regional reconstruction of subsistence economy. agricultural villages ceramic technology cultigens forest clearing human occupation References Cited Several major sites by AD 200 Monagrillo style pottery ca. 3300 BC Rockshelters at Parita Bay ca. 9000 BC Lake La Yeguada watershed ca. 11,000 BC Paleoindian settlements ca. 9500 BC 46.67 38.51 30.56 27.69 15.38 10.13 2.78 2.78 Polychrome style from Coclé CM GRAN CHIRIQUÍ Villages in Bocas del Toro by AD 500 Aguas Buenas style pottery ca. AD 0 Present in rockshelters ca. 3700 BC Laguna Volcan watershed ca. 4000 BC Preceramic rockshelters ca. 6000 BC Aguas Buenas style from Chiriquí CM Sitio Drago 9.33 8.00 9.23 1 km Cave 2 Cave 3 Sitio Teka N Cave 1 ISLA COLÓN Ceramic Site ALMIRANTE BAY SITIO DRAGO Recently discovered 17-ha. Ceramic period village site located on Isla Colón, the largest island in the Bocas del Toro Archipelago. Radicarbon dates place occupation at AD 700 to beyond Spanish contact (ca. 1500). Sitio Drago is larger and contains a greater diversity of artifact types in comparison to previously recorded sites in Gran Chiriquí6. Fifteen shell mounds and a cemetery contain a variety of ceramics, lithics, shell beads, metal artifacts, and shell trumpets in both routine and feasting contexts. The ceramic assemblage includes local wares and vessels imported from Costa Rica, Nicaragua, and the Pacific Gran Coclé. Nearby forest locales contain additional activity areas, including smaller sites, rockshelters, and 65 milling stones imported from off-island sources. Recent discovery of sites nearby on the mainland suggests Sitio Drago was not an isolated settlement in the region. Nicoyan polychrome Chocolate incised style from Pacific Costa Rica Irazu yellow-on-red style from montane Costa Rica 1.35 Late Preceramic (6000-3300 BC) Palm Early Ceramic (3300-400 BC) Fruit Tree Middle to Late Ceramic (400 BC - AD 1500) Maize CM Abundance of primary plant food resource types, ranked by ubiquity value (% samples present/total number of samples), demonstrates increased importance of maize through time. Types of Data Available Macrobotanical Microbotanical Pollen diagram PACIFIC OCEAN PLANT USE IN GRAN COCLÉ Early Preceramic (8500-6000 BC) Pearl Islands Coyol palm Acrocomia vinifera 9.26% ANCIENT PANAMÁ LOWER CENTRAL AMERICA GRAN COCLÉ Coiba Island Azuero Peninsula Yagua palm Attalea butyracea 9.57% 50 45 40 35 30 25 20 15 10 5 0 Sitio Gandoca del Toro Sitio Drago Bocas Archipelago SE Maya Borderlands Ficus tree Ficus sp. 9.88% CARIBBEAN SEA (after Cooke 2005; Dickau 2010) GRAN CHIRIQUÍ BT-IC-10 BT-IC-23 BT-IC-20 F09 BT-IC-21 BT-IC-22 BOCA DEL DRAGO 5 km Major Archaeological Sites in Panamá (boundaries approximate) Ceramic Site BT-IC-3 Archaeologists know little about the development and persistence (ca. AD 200-1500) of middle-range societies in Lower Central America (LCA). Current models rely heavily on untested assumptions about political organization and subsistence economy1,2. Sitio Drago, a village site located on an island along the Caribbean coast of Western Panamá, provides critical data that will begin filling these analytical gaps3. This project seeks to establish a baseline of plant resource use in the region using archaeobotanical data. Cultural Regions ca. AD 500 Archaeological Sites Identified on Isla Colón Maize Zea mays 7.72% Bactris palm Bactris mayor 6.16% Nance Byrsonima crassifolia 5.56% Macaw palm Acrocomia aculeata 4.01% CM CM FUTURE WORK This project aims to expand upon previous paleoethnobotanical studies in the region by developing a reconstruction of agricultural activities during the Late Ceramic period in Western Panamá. During summer 2012, floral remains will be collected through vertical column sampling of units excavated on Isla Colón. During the 2012-2013 academic year, I will identify macrobotanical remains, procure radiocarbon dates to confirm stratigraphy of deposits, and conduct phytolith and starch grain analysis of sediment samples and stone tool residue. Results will test three hypotheses: (1) people at Sitio Drago engaged in staple plant food production, (2) people at Sitio Drago increased crop production of maize and/or tubers during the Late Ceramic period, and (3) people in Central and Western Panamá developed regional differences in subsistence strategy. Understanding the development and persistence of LCA chiefdoms is essential to addressing questions of emergent political complexity and cultural continuity in the region. Sitio Drago may provide evidence of the first large agricultural village located in Gran Chiriquí, thus enabling a more robust comparison of Western Panamá villages with settlements located in neighboring regions. Empirical reconstructions of farmers’ activities will complement top-down theoretical frameworks addressing the development of political, economic, and social organization in ancient Panamá. Addressing the extent to which prehistoric villagers relied on food production requires quantitative asessment of macrobotanical evidence. I began by analyzing previously identified floral remains 5 from 12 sites in Gran Coclé . This study produced a list of 26 plant types, many of which have known economic value. Ubiquity values indicate importance of palms through time. Changes in ranking order can indicate a preference for certain plant types in relation to each other. Maize becomes the top-ranked plant resource in terms of ubiquity values during the Middle to Late Ceramic period, concurrent with developments in ceramic technology, long-distance trade, and social inequality. [1] Linares, O. F. and A. J. Ranere (eds). 1980. Adaptive Radiations in Prehistoric Panama. Peadbody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard Univ., Cambridge. [2] Sharer, R. J. 1983. Lower Central America as Seen from Mesoamerica. In The Archaeology of Lower Central America, ed. by F. W. Lange and D. Z. Stone, pp. 63-84. School of American Research advanced seminar series. Univ. of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque. [3] Wake, T. A., J. de Leon and C. F. Bernal. 2004. Prehistoric Sitio Drago, Bocas del Toro, Panama. Antiquity 78(300). [4] Cooke, R. 2005. Prehistory of Native Americans on the Central American Land-Bridge: Colonization, Dispersal and Divergence. Journal of Archaeological Research 13(2):129-187. [5] Dickau, R. 2010. Microbotanical and Macrobotanical Evidence of Plant Use and the Transition to Agriculture in Panama. In Integrating Zooarchaeology and Paleoethnobotany: A Consideration of Issues, Methods, and Cases, ed. by A. M. VanDerwarker and T. M. Peres, pp. 99-134. Springer, New York. [6] Wake, T. A. and T. Mendizábal. In press. Sitio Drago (Isla Colón, Bocas del Toro, Panamá): Un Aldea y Centro de Intercambio en el Caribe Panameño. In Mucho Más que un Puente Terrestre: Avances de la Arqueología Panameña y sus Implicaciones en el Contexto Regional, edited by J. G. Martín and R. G. Cooke, pp. x-x. Patronato Panamá Viejo, Panama City. Acknowledgements I would like to thank Dr. Richard Lesure (UCLA) for supervising this project, Dr. Thomas Wake (CIOA-UCLA) for directing the field project, Dr. Amber VanDerwarker (UCSB) for methodological guidance, and Dr. Jeanne Arnold (UCLA), Dr. Greg Schachner (UCLA), and the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA for additional support. Dr. Ruth Dickau (University of Exeter) kindly provided access to data and field notes. Michael Davis (Univ. of Kansas) provided maps of archaeological work on Isla Colón. Funding is provided by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship, the UCLA Graduate Division, and the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology.