Progressive states?1 ÁNGELES CARRASCO GUTIÉRREZ

Anuncio

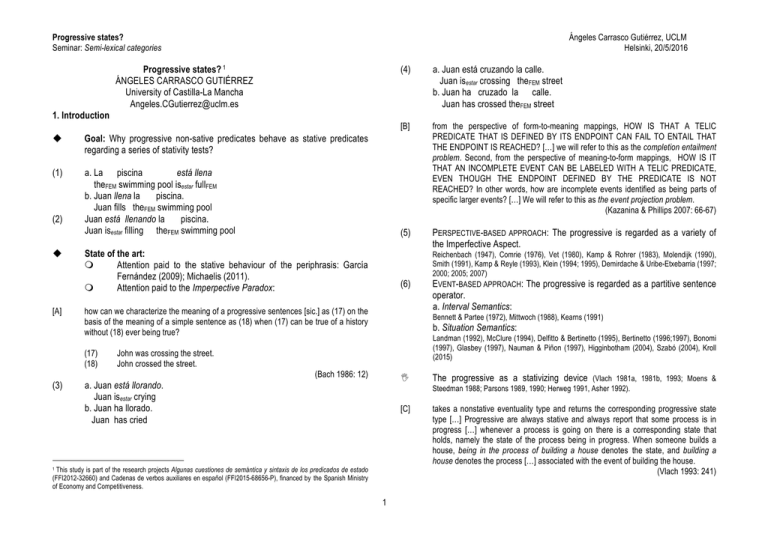

Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 Progressive states? 1 ÁNGELES CARRASCO GUTIÉRREZ University of Castilla-La Mancha [email protected] (4) a. Juan está cruzando la calle. Juan isestar crossing theFEM street b. Juan ha cruzado la calle. Juan has crossed theFEM street [B] from the perspective of form-to-meaning mappings, HOW IS THAT A TELIC PREDICATE THAT IS DEFINED BY ITS ENDPOINT CAN FAIL TO ENTAIL THAT THE ENDPOINT IS REACHED? […] we will refer to this as the completion entailment problem. Second, from the perspective of meaning-to-form mappings, HOW IS IT THAT AN INCOMPLETE EVENT CAN BE LABELED WITH A TELIC PREDICATE, EVEN THOUGH THE ENDPOINT DEFINED BY THE PREDICATE IS NOT REACHED? In other words, how are incomplete events identified as being parts of specific larger events? […] We will refer to this as the event projection problem. (Kazanina & Phillips 2007: 66-67) (5) PERSPECTIVE-BASED APPROACH: The progressive is regarded as a variety of the Imperfective Aspect. 1. Introduction u Goal: Why progressive non-sative predicates behave as stative predicates regarding a series of stativity tests? (1) a. La piscina está llena theFEM swimming pool isestar fullFEM b. Juan llena la piscina. Juan fills theFEM swimming pool Juan está llenando la piscina. Juan isestar filling theFEM swimming pool (2) u [A] State of the art: m Attention paid to the stative behaviour of the periphrasis: García Fernández (2009); Michaelis (2011). m Attention paid to the Imperpective Paradox: (6) operator. a. Interval Semantics: how can we characterize the meaning of a progressive sentences [sic.] as (17) on the basis of the meaning of a simple sentence as (18) when (17) can be true of a history without (18) ever being true? (17) (18) Bennett & Partee (1972), Mittwoch (1988), Kearns (1991) b. Situation Semantics: Landman (1992), McClure (1994), Delfitto & Bertinetto (1995), Bertinetto (1996;1997), Bonomi (1997), Glasbey (1997), Nauman & Piñon (1997), Higginbotham (2004), Szabó (2004), Kroll (2015) John was crossing the street. John crossed the street. (Bach 1986: 12) (3) Reichenbach (1947), Comrie (1976), Vet (1980), Kamp & Rohrer (1983), Molendijk (1990), Smith (1991), Kamp & Reyle (1993), Klein (1994; 1995), Demirdache & Uribe-Etxebarria (1997; 2000; 2005; 2007) EVENT-BASED APPROACH: The progressive is regarded as a partitive sentence I a. Juan está llorando. Juan isestar crying b. Juan ha llorado. Juan has cried The progressive as a stativizing device (Vlach 1981a, 1981b, 1993; Moens & Steedman 1988; Parsons 1989, 1990; Herweg 1991, Asher 1992). [C] This study is part of the research projects Algunas cuestiones de semántica y sintaxis de los predicados de estado (FFI2012-32660) and Cadenas de verbos auxiliares en español (FFI2015-68656-P), financed by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness. 1 1 takes a nonstative eventuality type and returns the corresponding progressive state type […] Progressive are always stative and always report that some process is in progress […] whenever a process is going on there is a corresponding state that holds, namely the state of the process being in progress. When someone builds a house, being in the process of building a house denotes the state, and building a house denotes the process […] associated with the event of building the house. (Vlach 1993: 241) Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories u Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 Hypothesis: The progressive construction selects an internal phase of the verbal process. 2.1. The test of cuando4 (8) m m m u <Estar + gerund> is not a stativizing device. The Progressive is a content of Phasal Aspect. The partitive character of the progressive follows from the relationship between the internal part of the process selected by the construction and the whole subeventive structure of the verbal predicate. (9) (10) Structure: Section 2: Stativity tests. Section 3: Proposals of García Fernández (2009) and Michaelis (2011). Section 4: Analysis of the progressive construction. Section 5: Main conclusions. 2. Stativity N N (7) E1 = The event of the main clause. E2 = The event of the embedded clause. _ = The event on the right follows the event on the left. , = The event on the right and the event on the left overlap. 2.2. The present tense test5 tests2 (11) The tests in sections 2.1-2.5 relate a verbal predicate to a punctual element: a temporal expression or a punctual event (the speech event and the embedding event).3 In the original tests Grammatical Aspect is ignored. A: B: (12) a. bailo (I dance), bailaba (I dancedIMP) IMPERFECTIVE: + + + - - - - [- - - - ] - - - - + + + b. bailé (I dancedPERF), he bailado (I have danced) PERFECTIVE: + + + + [+ - - - - - +] + + + + + Time of the Situation: Time posterior or anterior to TSIT: Topic Time: E2_E1: Cuando baje el telón, cerrarán las puertas. when comes-down the curtain, will-close3.PL theFEM.PL doors E1,E2: Cuando baje el telón, las puertas estarán cerradas. when comes-down the curtain, the FEM.PL doors will-beestar closedFEM.PL E1,E2 Cuando baje el telón, estarán cerrando las puertas. when comes-down the curtain, will-beestar.3.PL closing the FEM.PL doors A: B: C: (13) ---++++ [] A: B: For the original versions of the tests see: García Fernández (2000), test 2.6; Katz (2003), tests 2.3, 2.5; and Michaelis (2011), tests 2.1, 2.2, 2.4. For simplicity, I will ignore the non-epistemic perception test, which establishes that neither infinitival stative predicates nor infinitival progressive non-stative predicates can be embedded under a verb of perception. To this respect, see García Fernández (2009: 254) and Carrasco Gutiérrez (in preparation). 3 For the definition of punctual event, see Giorgi & Pianesi (1995: 346): “... an event is punctual if and only if it is not partitioned by other events, i.e. if and only if there are no events that overlap it and do not overlap each other.” ¿Cómo está la piscina ahora? how isestar theFEM swimming pool now? Está llena. isestar fullFEM ¿Qué hace Juan ahora? what does Juan now? ?Llena la piscina. fills theFEM swimming pool Está llenando la piscina. isestar filling theFEM swimming pool ¿Qué hace Juan cada verano? what does Juan every summer? Llena la piscina. fills theFEM swimming pool 2 This test is proposed by Vlach (1981a: 67; 1981b: 275). Consult also Vlach (1993: 239-240) and Moens (1987: 13), where the accesibility test of Vuyst (1983) is mentioned. 5 The present tense test is equivalent to the test of seem (Mittwoch 1988: 233). 4 2 Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories C: ?Está isestar Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 llenando la piscina. filling theFEM swimming pool (16) E1,E2: que Juan estaba llenando la piscina (en ese momento). that Juan wasestar.IMP filling theFEM swimming pool (in that moment) 2.3. The test of deber6 2.5. The test of the infinitival complements of believe, know, think (14) a. La piscina debe (de) estar llena. theFEM swimming pool must (of) beestar fullFEM b. Juan debe de llenar la piscina #(cada verano). Juan must of fill theFEM swimming pool (every summer) b’. Juan debe llenar la piscina. Juan must fill theFEM swimming pool c. Juan debe (de) estar llenando la piscina. Juan must (of) beestar filling theFEM swimming pool (17) (18) Deber de = EPISTEMIC READING Deber = DEONTIC READING 2.4. The indirect discourse test (15) 6 María dijo… María saidPERF E1,E2: a. que la piscina estaba llena (en ese momento). that theFEM swimming pool wasestar.IMP fullFEM(in that moment) b. que Juan llenaba la piscina (?en ese momento). that Juan filledIMP theFEM swimming pool (in that moment) E2_E1: c. que la piscina estuvo llena. that theFEM swimming pool wasestar.PERF fullFEM d. que Juan llenó la piscina. that Juan filledPERF theFEM swimming pool B: [(24) & (25) in Michaelis (2011: 1369).] a. Juan cree estar lleno de sospechas. Juan believes to beestar full of suspicions b. Juan cree llenar la piscina. Juan believes to fill theFEM swimming pool c. Juan cree estar llenando la piscina. Juan believes to beestar filling theFEM swimming pool u Conclusions from sections 2.1-2.5: m The overlapping relationships are only possible with Imperfective verbal forms. The Imperfective reading is the more natural interpretation of stative and progressive non-stative predicates with Neutral Aspect morphology; the Perfective reading is the more natural interpretation of non-stative predicates. Non-progressive non-stative predicates with Imperfective morphology show more resistance to be employed to express overlapping. m m 2.6. The <al+infinitive> test (19) The same effect is obtained with the future tense (García Fernández 2009: 255-256): A: a. I believe my senators to favor health care reform. b. *I believe my senators to vote for health care reforms. ¿Y Juan? and Juan Estará dormido/ #Dormirá/ Estará durmiendo. will-beestar.3.SG slept/ will-sleep3.SG/ will-beestar.3.SG sleeping. 3 TEMPORAL READING: AL = ‘AS SOON AS’ a. Al salir el sol, los excursionistas reanudaron la marcha. at-the rise the sun, thePL hikers resumedPERF theFEM walk b. Al tocar la orquesta el himno nacional, la multitud at-the play theFEM orchestra the anthem national, theFEM crowd se enardeció. [(88b) in García Fernández (2000: 283).] got-enthusiastic Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories (20) Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 CAUSAL READING: AL = ‘BECAUSE, GIVEN THAT’ a. Al estar despiertos, los excursionistas reanudaron la marcha. at-the beestar awakePL, thePL hikers resumedPERF theFEM walk b. Al estar saliendo el sol, los excursionistas reanudaron la marcha. at-the beestar rising the sun, thePL hikers resumedPERF theFEM walk 1 2 Why would a periphrasis of Grammatical Aspect modify the way in which a non-stative predicate is conceived? Instantaneous situations are not stative. (24) a. Son las 15:00 en punto. Juan está hambriento. [est] areser theFEM 15:00 o’clock. Juan isestar hungry b. Son las 15:00 en punto. Juan está comiendo. [est1+est2+…estn] arese theFEM 15:00 o’clock. Juan isestar eating 3. Two approaches to the stativity of the progressive periphrasis 3.1. García Fernández (2009) <Estar + gerund> causes the event to be divided into an indefinite sequence of instantaneous states. 3 What comes into focus may be a strecht of time. Compatibility with the morphology of Perfective aspect. (21) a. Juan va a la Universidad. Juan goes to theFEM University b. e1+e2+en a. Juan está yendo a la Universidad. Juan isestar going to theFEM University b. est1+est2+…estn (25) Durante la reunión, Juan estaba comiendo. during theFEM meeting, Juan wasestar.IMP eating Juan estuvo llenando la piscina. Juan wasestar.PERF filling theFEM swimming pool (22) (26) 4 The stativity of the auxiliary does not guarantee the stativity of the periphrasis. (27) THE TEST OF CUANDO a. Cuando baje el telón, las puertas serán cerradas. when comes-down the curtain, theFEM.PL doors will-beser closedFEM.PL THE TEST OF DEBER b. La piscina debe de ser llenada #(cada verano). theFEM swimming pool must of beser filledFEM (every summer) 5 Not all the stative predicates become non-stative. (28) *Juan está siendo alto. Juan isestar beingser tall [(6) & (7) in García Fernández (2009: 249).] <Estar + gerund> instantiates the progressive value of the Imperfective Aspect. [D] …le condizioni più importanti per definiré l’Aspetto progressivo sembrano essere le tre seguenti: (A) esistenza di un istante di focalizzazione tf; (B) prosecuzione indeterminata del proceso oltre tf; (C) semelfactività. (Bertinetto 1986: 125) <Estar + gerund> inherits its stativity from the auxiliary verb. <Estar + gerund> selects non-stative predicates. (23) a. Juan es tonto. Juan isser stupid b. Juan está siendo tonto. Juan isestar beingser stupid [(59b) in García Fernández (2009: 266).] 3.2. Michaelis (2011) [E] [(4a) & (4b) in García Fernández (2009: 247).] 4 Stativizing constructions do not create states out of thin air. Rather […] stativizing constructions evoke states that are contained in the event representations of verbs. Michaelis (2011: 1364) Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories u Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 The stative auxiliary selects a medial rest from an activity representation. AKTIONSART CLASS States Homogeneuous activities Heterogeneous activities Achievements Accomplishments TABLE 1 TEMPORAL REPRESENTATION φ τφτ τφ[τφ]+τ τφ τφ[τφ]+τφ 4. The stativity of <estar + gerund> reconsidered 4.1. States, processes and actions7 EXAMPLE PREDICATION prefer- white wine stand- on one foot pace -back and forth stand -up drive -home (32) a. STATE: La piscina está {llena/ allí}. theFEM swimming pool isestar fullFEM/there} b. PROCESS: La piscina se llenó. theFEM swimming pool was-filledPERF c. ACTION:8 Juan llenó la piscina. Juan filledPERF the swimming pool (33) INSTANTANEOUS PROCESS marcar un gol (‘score a goal’): ssource ⇒ starget NON-INSTANTANEOUS PROCESS ORIENTED TO THE PATH correr por el parque (‘run through the park’) s1 ⇒ s2 ⇒ … ⇒ sn NON-INSTANTANEOUS PROCESS NOT ORIENTED TO THE PATH llenar(se) la piscina (‘fill the swimming pool’) ssource ⇒ s1 ⇒ s2 ⇒ … ⇒ starget φ = non-punctual stretches of time called phases τ = temporal boundaries; state-change events called transitions (29) a. Homogeneous activity: …τφτ …. b. Heterogeneous activity: …τφτ…τφτ…τφτ…τφτ… [F] Antecedent states and consequent states – as well as periods of stasis which lie between chained events- can be subsumed under the rubric of rests. The term rest is meant to be construed as it is in rhythmic representation: a pause between “beats”, or transitions. (Michaelis 2004: 16) (30) a. Homogeneous activity: …τ φ τ …. (34) (35) é b. Heterogeneous activity: …τφτ … τφτ … τφτ … τφτ… é or é or é Progressive is a coercion trigger. (31) a. OK. I’m really liking Windows 7. b. More poors are living in suburbs, a Brookings study says. ⇒ = transtition between two states ssource = initial state; starget = final state; s1, s2, sn = intermediate states 4.2. <Estar + gerund> as a phasal aspect periphrasis 4.2.1. The superlexical morpheme estar [(43) & (44) in Michaelis (2011-1375-1376).] [G] The rests from which the progressive selects in (33a) and (33b) are qualitatively different. The addition of onset and offset transitions is not always possible. Speakers may present a situation as a whole, with a BROAD VIEW. Or they may take a NARROW VIEW, talking about the endpoints or the middle of a situation […] Languages convey broad and narrow views of a situation in various ways. In English, See Moreno Cabrera (2003: 171-198) for a critical review of the proposals of McCawley (1968), Jackendoff (1972; 1990), Dowty (1979), Pustejovsky (1991; 2000), Levin & Rappaport Hovav (1995), Mateu Fontanals (1997), and Van Valin & LaPolla (1997), among others. 8 Actions inherit the aspectual structure of the processes: Juan marcó un gol (‘Juan scored a goal’) would be an action of achievement; Juan corrió por el parque (‘Juan ran through the park’), an activity action; and Juan llenó la piscina (‘Juan filled the swimming pool’) an action of accomplishment (see Moreno Cabrera 2011: 10). 7 5 Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 the broad view is usually given in a simple sentence, e.g., Mary builts a sandcastle, and the narrower views with verbs or phrases that have the simple sentence as a complement, for instance, Mary began building a sandcastle; Mary is in the process of building a sandcastle; Mary finished building a sandcastle […] I refer to morphemes that give a narrow view of a situation as “SUPERLEXICAL” MORPHEMES. (Smith 2005: 229-230) [H] Estar is merged above the small clause. The main characteristic of estar is that it contains an interpretable feature of terminal coincidence [iRT] that is able to value its uninterpretable counterpart in RT. The copula is the element that denotes the notion of abtract path, whose motivation is to locate a figure (the subject) by associating it with a ground (the entity included in the attribute) by means of a terminal coincidence relation. The ground is conceived as an external property.9 B) AUXILIARY ESTAR (Brucart 2010, 2012) The path is not abstract, but physical. (36) ATTRIBUTIVE ESTAR: a. El decanato está {subiendo/bajando} la escalera. the Dean’s-Office isestar {going-up/going-down} theFEM stairs The Imperfective can be assumed to have a unified semantic content which can be described in such terms as “non-complete, not-bounded, divisible, open”. This semantic content can, in actual usage, get several more specific interpretations, such as “progressive” (SoA presented as ongoing), “habitual” (recurrent by virtue of habit), “iterative” (occurring repeatedly), and “continuous” (occurring continuously, without interruption or endpoint). We shall assume that these different interpretations of the Imperfective must be distinguished from the distinct grammatical aspect values Progressive, Habitual, Iterative, Continuous […] Thus, the English Progressive, though it expresses one facet of what may be covered by the Imperfective of other languages, is not itself to be equated with Imperfective Aspect. We shall consider the English Progressive as one type of “Phasal Aspect”. (Dik 1989 [1997: 223]) [(43a) in Brucart (2010: 138).] [I] State of Affairs (37) 1 -------------------------------------------------------2-------------------------------------------------->3 The SoA begins at 1, continues through 2, and ends at 3. Aspectual distinctions relevant to this internal development of the SoA would be: (16) a. Ingressive b. Progressive c. Continuous d. Egressive L= Location P= property ‘John started crying’ ‘John was crying’ ‘John continued crying’ ‘John stopped crying’ (38) (Dik 1989 [1997: 223]) 4.2.2. The definite terminal coincidence relation A) ATTRIBUTIVE ESTAR (Brucart 2010, 2012) AUXILIARY ESTAR: b. María está subiendo la escalera. María isestar going-up theFEM stairs PATH CONSTITUTED OF LOCATIVE STATES: María está subiendo la escalera. a. Lsource (María) ⇒ L1 (María) ⇒ L2 (María) ⇒…⇒ Ltarget (María) PATH CONSTITUTED OF ATTRIBUTIVE STATES: Juan está llenando la piscina. b. Psource (piscina) ⇒ P1 (piscina) ⇒ P2 (piscina) ⇒…⇒ Ptarget (piscina) The structure of attributive sentences includes a small clause.The head of the small clause is a relational element conceptualized as an abstract preposition of terminal coincidence: RT. 9 6 a. *Juan está siendo alto. Juan isestar beingser tall b. *María está encontrando el libro. María isestar finding the book s ssource ⇒ starget Coincidence is defined as a temporal, spatial or identity relation between two elements, one functioning as a figure, and the other being a ground. In central coincidence the figure coincides with the ground at the center of the trajectory. In terminal coincidence, the figure and the ground do not coincide at the center of the trajectory, so the path is convergent or divergent. (Brucart 2012: 17, footnote 9) Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 The gerund would instantiate the notion of central coincidence. The predicate is coerced to be interpreted as delimited. (43) We found part of a Roman aqueduct. [(21) in Bach (1986: 12).] [J] The relation that characterizes the gerundive clause in the last example [Juan está corriendo a la esquina (‘Juan is running to the corner’)] is of central coincidence, whereby THE FUNCTION OF ESTAR IN THIS CASE IS NOT CHECKING A TERMINAL COINCIDENCE FEATURE IN THE ATTRIBUTE, BUT SUPERIMPOSING ITS OWN ASPECTUAL MARK OVER THE GERUNDIVE CLAUSE IN ORDER TO FOCUS AN INTERNAL PHASE OF THE EVENT (PROGRESSIVE INTERPRETATION). (Brucart 2012: 28, footnote 16) m The event projection problem ß The internal phase selected by <estar + gerund> should be characterized differently depending on the type of predicate. (44) La piscina está {apenas/medio/casi/totalmente} llena. theFEM swimming pool isestar {barely/half/almost/totally} fullFEM llenar(se) la piscina (‘to fill the swimming pool’) (45) (39) [AspgrammaticalP …. [Aspphasal P …. estar + -ndo …. [RTP … ]]] u Proposal: 4.3.2. Estar siendo tonto10 m m m m It is not necessary to equate non-abstract path with displacement. The progressive periphrasis is not a coerced construction. AspgrammaticalP has scope over Aspphasal P. The predicate structure above wich estar is merged instantiates the relation of indefinite terminal coincidence. That relation becomes definite due to estar, which exerts its delimiting function so that an internal phase of the path is selected. (46) (40) llena0 (piscina) ⇒ llena1/10(piscina) ⇒… ⇒ llena9/10(piscina) ⇒ llena1 (piscina) (47) (48) INTERNAL PHASE: <sx ⇒ … ⇒ sy> (49) x ≠ source or 1 y ≠ goal or n (41) (42) IMPERFECTIVE ASPECT: PERFECTIVE ASPECT: <sx ⇒ [ …] ⇒sy> [⇒ <sx ⇒ …⇒ sy> ⇒] JUAN ES ALTO (‘JOHN IS TALL’) Σ (Juan, λx [Alto (x)]) JUAN ES TONTO (‘JOHN IS STUPID’) Σ (Juan, λx [Tonto1 (x) ⇒ … ⇒ Tonton (x)])11 a. Tonto (x) b. T1 (x) ⇒ … ⇒ Tn (x) c. λx [Tonto1 (x) ⇒ … ⇒ Tonton (x)] d. Tonto1 (Juan) ⇒ … ⇒ Tonton (Juan) JUAN ESTÁ SIENDO TONTO: <Tx (Juan) ⇒, …, ⇒ Ty (Juan) > x ≠ source or 1 y≠ target or n Topic Time: [ ] Time of the internal phase: it is shadowed 4.3. Aspect matters 4.3.1 The imperfective paradox m The completion entailment problem ß The internal phase selected by <estar + gerund> realizes sufficiently much of the verbal event. On this matter, consult Wilkinson (1970; 1976), Dowty (1975), Partee (1977), Rivière (1983), Hirtle & Bégin (1991), Stowell (1991), Bickel (1996), Espunya I Prat (1996), Zucchi (1998), Barker (2002), Arche (2004), Kertz (2006), Martin (2006; 2015), Landau (2006), Oshima (2009), Jóhannsdóttir (2011), Krivochen & Schmerling (2015). 11 I am indebted to Juan Carlos Moreno Cabrera for this suggestion. 10 7 Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 4.3.3. The stativity tests PREDICATE CLASSES Stative predicates 5. Main conclusions OVERLAPPING RELATION (9), (18a) • â <Estar + gerund> is a Phasal Aspect construction compatible with different contents of Grammatical Aspect. The auxiliary estar is merged above structures that instantiate the relation of indefinite terminal coincidence between the subject and the path of intermediate states the subeventive structure of the verbal predicate is constituted of. Progressive non-stative predicates behave as stative ones because: (a) their delimiting function make possible to identify an internal phase of the verbal process that can undergo a inclusion relation with overlapping punctual elements; and (b) they reject the inceptive interpretation. EXAMPLES (11B), (14a), (15a), s TABLE 2. RELATION WITH A PUNCTUAL ELEMENT. STATIVE PREDICATES • = punctual element â= connection between the verbal situation and the punctual element PREDICATE CLASSES Non-stative progressive states OVERLAPPING RELATION • â EXAMPLES (10), (12C vs. 13C), (14c), (16), (18c) 6. References <…[su ⇒ sw]…> TABLE 3. RELATION WITH A PUNCTUAL ELEMENT. PROGRESSIVE NON-STATIVE PREDICATES PREDICATE CLASSES OVERLAPPING RELATION EXAMPLES Non-stative non-progressive states • å â æ […] […] […] (8), (12B vs. 13B), (14b), (15b) (18b) TABLE 4. RELATION Arche, Mª Jesús (2004): Propiedades aspectuales y temporales de los predicados de individuo, PhD. Dissertation, Complutense University, Madrid. Asher, Nicholas (1992): “A default, truth conditional semantics for the progressive”, Linguistics and Philosophy 15/5, 463-508. Bach, Emmon (1986): “The algebra of events”, Linguistics and Philosophy 9, 5-16. Barker, Chris (2002): “The dynamics of vagueness”, Linguistics and Philosophy 25,1-36. Bennett, Michael (1977): “A guide to the logic of tense and aspect in English”, Logique et Analyse 20, 491-517. Bennett, Michael and Barbara Hall Partee (1972): Toward the logic of tense and aspect in English, Bloomington, Indiana, Indiana University Linguistics Club. Bertinetto, Pier Marco (1986): Tempo, Aspetto e Azione nel verbo italiano. Il sistema dell’indicativo, Firenze, L’Accademia della Crusca. ______, (1994a): “Statives, progressives and habituals: analogies and differences”, Linguistics 32, 391-423. ______, (1994b): “Le perifrasi abituali in italiano ed in inglese”, Quaderni del Laboratorio di Linguistica 8, 32-41. [Also in: 1994/1995: Studi Orientali e Linguistici 6, 117-133; and in: 1997: Il dominio tempo-aspettuale. Demarcazioni, intersezioni, contrasti, Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier, chapter 9.] ______, (1996): “Notes on the progressive as a ‘partialization’ operator”, Quaderni Laboratorio di Linguistica della SNS, 10. ______, (1997): “The progressive as a ‘partialization’ operator”, in Il dominio tempo-aspettuale. Demarcazioni, intersezioni, contrasti, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier, 95-110. Bickel, Balthasar (1996): Aspect, mood, and time in Belhare: studies in the semantics-pragmatics interface of a Himalayan language, ASAS, Arbeiten des Seminar für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft, 15, University of Zürich. ______, (1997): “Aspectual scope and the difference between logical and semantic representation”, Lingua 102, 115131. Binnick, Robert I. (1991): Time and the verb. A guide to Tense & Aspect, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Bonomi, Andrea (1997) “The progressive and the structure of events”, Journal of Semantics 14/2, 173-205. Brucart, José María (2010): “La alternancia ser/estar y las construcciones atributivas de localización”, in Alicia Avellana (comp.): Actas del V encuentro de Gramática Generativa, Neuquén, Comahue University Press, 115-152. ______, (2012): “Copular alternation in Spanish and Catalan attributive sentences”, Revista de Estudos Linguísticos da Universidade do Porto 7, 9-43. ssource ⇒s1 ⇒…⇒ starget WITH A PUNCTUAL ELEMENT. NON-PROGRESSIVE NON-STATIVE PREDICATES (50) a. Cuando bajó el telón, Juan tuvo miedo. when came-downPERF the curtain, Juan hadPERF fear b. *Cuando bajó el telón, las puertas estuvieron cerradas. when came-downPERF the curtain theFEM.PL doors was estar.PERF closedFEM.PL c. *Cuando bajó el telón, estuvo cerrando las puertas. when came-down the curtain, wasestar. .PERF closing the FEM.PL doors 8 Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 ______, (2014): “Cópulas, auxiliares y la noción de coincidencia”, V Seminario de Investigación en Tiempo y Aspecto, University of Castilla-La Mancha, Faculty of Arts, Ciudad Real (18-19 September 2014). Carrasco Gutiérrez, Ángeles (2004): “Algunas explicaciones para la simultaneidad en las oraciones subordinadas sustantivas”, in Luis García Fernández and Bruno Camus Bergareche (eds.): El pretérito imperfecto, Madrid, Gredos, 407-480. ______, (2014): “Non epistemic perception and subeventive structure”, Revista de Estudos Linguísticos da Universidade do Porto 9, 9-34. ______, (2015): “Perfect states”, Borealis. An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 4/1,1-30. ______, (in preparation): “¿Estados progresivos?”, Moenia 23. Carrasco Gutiérrez, Ángeles and Raquel González Rodríguez (2011): “La percepción visual de estados”, in Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez (ed.): Sobre estados y estatividad, Munich, Lincom Europa, 158-188. Comrie, Bernard (1976): Aspect. An introduction to the study of verbal aspect and related problems, Cambridge, MA, Cambridge University Press. Declerck, Renaat (1979): “On the progressive and the ‘imperfective paradox’”, Linguistics and Philosophy 3, 267-272. ______, (1981): “On the role of progressive aspect in nonfinite perception verb complements”, Glossa, 15, 83-113. ______, (1991): Tense in English. Its structure and use in discourse, London, Routledge. Delfitto, Denis and Pier Marco Bertinetto (1995): “A Case Study in the Interaction of Aspect and Actionality: The Imperfect in Italian”, in Pier Marco Bertinetto, Valentina Bianchi, James Higginbotham and Mario Squartini (eds.): Temporal Reference, Aspect and Actionality. 1: Semantic and Syntactic Perspectives, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier, 125142. Demirdache, Hamida and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria (1997): “The syntax of temporal relations: A uniform approach to tense and aspect”, in Emily Curtis, James Lyle and Gabriel Webster (eds.): Proceedings of the 16th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Stanford, CA, CSLI Publications,145-159. ______, (2000): “The Primitives of Temporal Relations”, in Roger Martin, David Michaels and Juan Uriagereka (eds): Step by Step: Essays on Minimalist Syntax in Honor of Howard Lasnik, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 157-186. ______, (2005): “Aspect and temporal modification”, in Paula Kempchinsky and Roumyana Slabakova (eds.): Aspectual inquieries, Dordrecht, Kluwer,191-221. ______, (2007): “The syntax of time arguments”, Lingua 117, 330-366. Dik, Simon C. (1989): The theory of Functional Grammar. Part 1: The structure of the clause, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, 1997, second edition. Dowty, David (1975): “The stative in the progressive and other essence/accident contrasts”, Linguistic Inquiry 6/4, 579588. ______, (1977): “Toward a semantic analysis of verb aspect and the English ‘imperfective’ progressive”, Linguistics and Philosophy 1/1, 45-77. ______, (1979): Word meaning and Montague grammar: The semantics of verbs and times in generative semantics and in Montague’s PTQ, Boston, Kluwer. ____, (1986): “The effects of aspectual class on the temporal structure of discourse: Semantics of Pragmatics?”, Linguistics and Philosophy 9, 37-61. Engelberg, Estefan (2002): “The semantics of the progressive”, in Cynthia Allen (ed.): Proceedings of the 2001 Conference of the Autralian Linguistic Society, http://www.als.asn.au. Espunya I Prat, Anna (1996): Progressive structures in English and Catalan, PhD. Dissertation, Autonomous University, Barcelona. Felser, Claudia (1999): Verbal complement clauses. A minimalist study of direct perception construction, Amsterdam, John Benjamins. Fiorin, Gaetano and Denis Delfitto (2014): “A perspective-based account of the imperfective paradox”, in Joanna Blochoviak, Cristina Grisot, Stéphanie Durrlemann-Tame and Christopher Laenzlinger (eds): Papers dedicated to Jacques Moeschler, Geneva. [www.unige.ch/lettres/linguistique/moeschler/Festschrift/ Festschrift.php] García Fernández, Luis (2000): La gramática de los complementos temporales, Madrid, Visor. ______, (2009): “Semántica y sintaxis de la perífrasis <estar + gerundio>”, Moenia 15, 245-274. Garey, Howard B. (1957): “Verbal aspect in French”, Language 33/2, 91-110. Giorgi, Alexandra and Fabio Pianesi (1995): “From semantics to morphosyntax: the case of the imperfect”, in Pier Marco Bertinetto, Valentina Bianchi, James Higginbotham and Mario Squartini (eds.): Temporal reference, aspect and actionality, vol. 1: Semantic and syntactic Perpectives, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier, 341-363. Glasbey, Sheila (1996): “The progressive: A channel-theoretic analysis”, Journal of Semantics 13/4, 331-361. Guasti, Maria Teresa (1993): Causative and perception verbs. A Comparative study, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier. Hale, Ken (1986): “Notes on world view and semantic categories: some warlpiri examples”, in Pieter Muysken and Henk van Riemsdijk (eds.): Features and projections, Dordrecht, Foris, 233-254. Hallman, Peter (2009): “Proportions in time: Interactions of quantification and aspect”, Natural language semantics 17, 29-61. Havu, Jukka (1997): La constitución temporal del sintagma verbal en el español moderno, Helsinki, Academia Scientiarum Fennica. Higginbotham, James (1983): “The logic of perceptual reports: an extensional alternative to situation semantics”, The Journal of Philosophy 80/2, 100-127. ______, (2004): “The English progressive”, in Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme (eds.): The syntax of time, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 173-193. ______, (2009): “The English progressive”, Tense, Aspect, and Indexicality, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 126-156. Hirtle, Walter H. and Claude Bégin (1991): “Can the progressive express a state?”, Langues et linguistique 17, 99-137. Herweg, Michael (1991): “Perfective and imperfective aspect and the theory of events and states”, Linguistics 29, 9691010. Jackendoff, Ray (1972): Semantic interpretation in Generative Grammar, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press. ______, (1990): Semantic structures, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press. ______, (1991): “Parts and boundaries”, Cognition 41, 9-45. Jóhannsdóttir, Kristín M. (2011): Aspects of the progressive in English and Icelandic, PhD Dissertation, British Columbia University, Vancouver. Kamp, Hans (1979): “Events, instants, and temporal reference”, in Rainer Bäuerle, Urs Egli and Arnim van Stechow (eds.): Semantics from different points of view, Berlin, Springer, 376-417. Kamp, Hans and Uwe Reyle (1993): From discourse to logic: An introduction to model-theoretic semantics of natural language, formal logic, and discourse representation theory, Dordrecht, Kluwer. Kamp, Hans and Christian Rohrer (1983): “Tense in Texts”, in Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze and Arnim von Stechow (eds): Meaning, use and interpretation of language, Berlin, Walter De Gruyter, 250-269. Katz, Graham (2003): “On the stativity of the English perfect”, in Artemis Alexiadou, Monika Rathert and Arnim von Stechow (eds.): Perfect explorations, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter, 205-234. Kazanina, Nina and Colin Phillips (2007): “A developmental perspective on the imperfective paradox”, Cognition 105, 65-102. Kearns, Katherine Susan (1991): The semantics of the English progressive, PhD. Dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Kertz, Laura (2006): “Evaluative adjectives: An adjunct control analysis”, in Donald Baumer, David Montero and Michael Scanlon (eds.): Proceedings of the 25th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, Sommerville, MA, Cascadilla Proceedings Project, 229-235. Klein, Wolfgang (1992): “The present perfect puzzle”, Language 68/3, 525-552. ______, (1994): Time in language, London, Routledge. ______, (1996): “A time relational analysis of Russian aspect”, Language 71/4, 669-695. Krivochen, Diego Gabriel and Susan F. Schemerling (2015): “On three apparent anomalies with the English progressive”, ms. Kroll, Nicky (2015): “Progressive teleology”, Philosophical Studies 172/11, 2931-2954. Laca, Brenda (2001): “El orden de las perífrasis verbales”, Cuadernos de Lingüística VII, University Institute Ortega and Gasset, 9-20. ______, (2004): “Romance ‘Aspectual’ Periphrases: Eventuality Modification versus ‘syntactic’ Aspect”, in Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme (eds.): The Syntax of Time, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press, 425-440. ______, (2005): “Périphrases aspectuelles et temps grammatical dans les langues romanes”, in Hava Bat-Zeev Shyldkrot and Nicole Le Querler (dirs.): Les périphrases verbales, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 47-66. 9 Progressive states? Seminar: Semi-lexical categories Ángeles Carrasco Gutiérrez, UCLM Helsinki, 20/5/2016 Landau, Idan (2006): “Ways of being rude”, ms. [http://www.bgu.ac.il/~idanl/ files/Rude%20Adjectives%20July06.pdf] ______, (2009): “Saturation and reification in adjectival diathesis”, Journal of Semantics 45, 315-361. Landman, Fred (1992): “The progressive”, Natural Language Semantics 1, 1-32. Lawers, Peter and Dominique Willems (2011): “Coercion: Definition and challenges, current approaches, and new trends”, Linguistics 49/6, 1219-1235. Levin, Beth and Rappaport, Malka (1995): Unaccusativiy: At the syntax-lexical semantics interface, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press. Martin, Fabienne (2006): Prédicats statifs, causatifs et résultatifs in discourse. Sémantique des adjectifs évaluatifs et des verbs psychologiques, PhD. Dissertation, Free University, Brussels. ______, (2015): “Relative stupidity and past tenses”, in Emmanuelle Labeau and Qiaochao Zhang (eds.): Taming the TAME systems (Cahiers Chronos 27), Amsterdam, Brill/Rodopi, 79-100. Mateu Fontanals, Jaume (1997): On relational semantics: a semantic theory of argument structure, PhD. Dissertation, Autonomous University, Barcelona. Mayerhofer, Ivan (2014): “In defense of the modal account of the progressive”, Mind & Language 29/1, 85-108. McCawley, James D. (1968): “Lexical insertion in transformational grammar without deep structure”, in Grammar and meaning. Papers on semantic and syntantic topics, Nueva York, Academic Press, 1976, 156-166. McClure, William Tsuyoshi (1994): Syntactic projections of the semantics of aspect, PhD. Dissertation, Cornell University. Michaelis, Laura A. (2004): “Type-shifting in Construction Grammar: An integrated approach to aspectual coerción”, Cognitive Linguistics 15/1, 1-67. ______, (2011): “Stative by constructions”, Linguistics 49/6, 1359-1399. Mittwoch, Anita (1988): “Aspects of English aspect: On the interaction of Perfect, progressive and durational phrases”, Linguistics and Philosophy 11, 203-254. Moens, Marc (1987): Tense, aspect and temporal reference, PhD. Dissertation, University of Edinburgh. Moens, Marc and Mark Steedman (1988) “Temporal ontology and temporal reference”, Computational linguistics, 1528. Molendijk, Arie (1990): Le passé simple et l’imparfait : une approche reichenbachienne, Amsterdam, Rodopi. Moreno Cabrera, Juan Carlos (2003): Semántica y gramática. Sucesos, papeles semánticos y relaciones sintácticas, Madrid, Antonio Machado Libros. ______, (2011): “La aspectualidad fásica de los estados resultativos desde el punto de vista de la Semántica Relacional de Sucesos (SRS)”, in Ángeles Carrasco (ed.): Sobre estados y estatividad, Munich, Lincom Europa, 8-25. Naumann, Ralph and Christopher Piñon (1997): “Decomposing the progressive”, in Paul Dekker, Martin Stokhof, and Yde Venema (eds): Proceedings of the Eleventh Amsterdam Colloquium, University of Amsterdam, Institute for Logic, Language and Computation, 241-246. Oshima, David Y. (2009): “Between being wise and acting wise: A hidden conditional in certain constructions with propensity adjectives”, Journal of Semantics 45, 363-393. Parsons, Terence (1989): “The progressive in English: Events, states and processes”, Linguistics and Philosophy 12/2, 213-241. ______, (1990): Events in the semantics of English. A study in subatomic semantics, Cambridge, MA, The MIT Press. Partee, Barbara (1977): “John is easy to please”, in Antonio Zampolli (ed.): Linguistic structures processing, Amsterdam, North Holland, 281-312. Pérez Saldanya, Manuel (2002): “Les relacions temporals i aspectuals”, in Joan Solà, Maria-Rosa Lloret, Joan Mascaró and Manuel Pérez Saldanya (dirs.): Gramàtica del català contemporani, Barcelona, Empúries, vol. 3, 2567-2662. Portner, Paul (1998): “The progressive in Modal Semantics”, Language 74/4, 760-787. Pustejovsky, James (1991): “The syntax of event structure”, Cognition 41, 47-81. [Also in: Mani Inderjeet, James Pustejovsky and Robert Gaizauskas (eds) (2005): The language of Time. A reader, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 33-60.] ______, (2000): “Events and the semantics of opposition”, in Carol L. Tenny and James Pustejovsky (eds.): Events as grammatical objects. The converging perspectives of lexical semantics and syntax, Stanford, CSLI Publications, 445-483. Reichenbach, Hans (1947): Elements of symbolic logic, Nueva York, MacMillan. Rivière, Claude (1983): “Modal adjectives: Transformations, synonymy, and complementation”, Lingua 59, 1-45. Rodríguez Espiñeira, Mª José (2000): “Percepción directa e indirecta en español. Diferencias semánticas y formales”, Verba 27, 33-85. Rohrer, Christian (1981): “Quelques remarques sur l’analyse de la forme progressive en anglais”, Langages 64, 29-38. Schmiedtová, Barbara (2004): The expression of simultaneity in learner varieties, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter. Smith, Carlota (1991): The parameter or aspect, Dordrecht, Kluwer. ______, (1996): “Aspectual categories in Navajo”, International Journal of American Linguistics 62/3, 227-263. Squartini, Mario (1998): Verbal periphrases in Romance. Aspect, actionality, and grammaticalization, Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter. Stowell, Tim (1991): “The alignment of arguments in adjective phrases”, in Susan Rothstein (ed.): Perspectives on phrase structure: Heads and licensing (Syntax and Semantics 25), NewYork, Academic Press, 101-135. Szabó, Zoltán Gendler (2004): “On the progressive and the perfective”, Noûs 38/1, 29-59. ______, (2008): “Things in progress”, Philosophical perspectives 22, 499-525. van Valin, Robert D. and LaPolla, Randy J. (1997): Syntax: structure, meaning and function, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Vet, Co (1980). Temps, aspects et adverbes de temps en français contemporain. Essai de sémantique formelle, Geneva, Librairie Droz. Vlach, Frank (1981a): “La sémantique du temps et de l’aspect en anglais”, Langages 64, 65-79. ______, (1981b): “The semantics of the progressive”, in Philip Tedeschi and Annie Zaenen (eds): Syntax and Semantics 14 (Tense and Aspect), New York, Academic Press, 271-292. ______, (1993): “Temporal adverbials, tenses and the perfect”, Linguistics and Philosophy 16, 231-283. Vuyst, Jan de (1983): “Situation-descriptions: Temporal and aspectual semantics”, in Alice G. B. ter Meulen (ed.): Studies in Model-Theoretic Semantics, Dordrecht, Foris, 161-176. Wilkinson, Robert (1970): “Factive complements and Active complements”, in Mary Ann Campbell et al. (eds.): Papers from the Sixth Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society 16-18 April, 425-444. ______, (1976): “Modes of predication and implied adverbial complements”, Foundations of Language 14/2,154-194. White, Michael (1993): “The imperfective paradox and the trajectory-of-motion events”, ACL ‘93 Proceedings of the 3st annual meeting on Association for Computational Linguistics, Stroudsburg, PA, 283-285. Wulf, Douglas J. (2009): “Two new challenges for the modal account of the progressive”, Natural Language Semantics 17, 2005-218. Zucchi, Sandro (1998): “Aspect shift”, in Susan Rothstein (ed.): Events and Grammar, Dordrecht, Kluwer, 349-370. ______, (1999): “Incomplete events, intensionality and the imperpective aspect”, Natural Language Semantics 7/2, 179-215. 10