The word “gothic” has, in general, been used in reference to

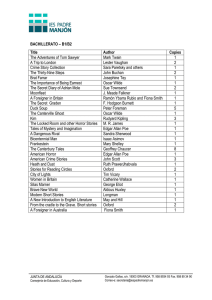

Anuncio