the costly price of christian love

Anuncio

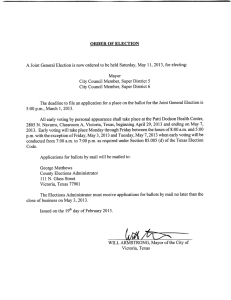

SAINTS JOURNEYING WITH US u AN ON-LINE PUBLICATION OF THE HAGIOGRAPHY CIRCLE vol. 1, no. 4 VICTORIA DÍEZ BUSTOS DE MOLINA: THE MOST ELOQUENT LESSON OF A MARTYRED EDUCATOR 1903-1936 I t’s her. It is her!” the young girl cried. “She did not see me, but it is her.” “Yes, Mamma,” affirmed another, “her hands were clasped and her eyes were cast downward… just like in church. She must have been praying... she was pale and alone.” They came upon hearing the news. One by one. Two by two. Some came with their mothers. In groups of three and four. The curious onlookers mixed with the sympathetic crowd hoping to catch a glimpse of the woman detained in the makeshift cell. She was alone, separated from the seventeen men who shared in the obscurity of her tomorrow. Indeed, they knew her… she was their teacher. GIFTED CHILD Victoria Díez Bustos de Molina was born on November 11, 1903 in the ancient city of Seville. She was the only child of José Díez Moreno and Victoria Bustos de Molina. They were a good Christian couple, morally upright and supportive of each other. The man of the house supported the family with his work in a commercial house in the city. José, however, was virtually shut off from his wife and daughter: he was deaf. It was quite a lonely life for him - and for the two women who consequently shared in his loneliness. VICTORIA DÍEZ BUSTOS DE MOLINA 1 SAINTS JOURNEYING WITH US The teachers of Victoria quickly noted her intelligence and talents. The young woman, known for her liveliness, affability and capacity to sacrifice, was also gifted with a talent for painting. On the same time, Victoria was remembered for her outstanding piety. Striving constantly to live in the presence of God, she nourished her spirituality with the sacraments, regular meditation and involvement in Catholic Action. The teaching profession did not immediately attract this future educator. The situation of her family and her own vivacious character made Victoria uncertain: “I do not know what God wants of me but I know that I do not have the vocation of a teacher.” Her parents had the last say, however, and acquiescing to their desires, Victoria enrolled at the Escuela Normal de Maestras of Seville in 1919. was formed by a fast growing number of intelligent and educated women who sought to make a difference in an increasingly secularized Spanish educational system. They had to struggle against the social forces of evil within the field of education and culture. Some of these women lived together as a group while others remained with their families to be as leaven to their communities. “I believe that I will only be happy by belonging to the Teresianas. How good God is who gives to each of us in the measure we desire!” At the same time that she entered the Internado Teresiano in 1926, Victoria decided to join the pious union. She became a member of the Institucion Teresiana on August 3, 1928. On July 9, 1932, she made her final commitment. TO GO TO THE ENDS OF THE EARTH DISCIPLE OF PEDRO POVEDA After graduating brilliantly in 1923, Victoria proceeded to take up higher studies. During its course, she underwent a crucial discernment process. From within her heart, Victoria felt an ardent desire to consecrate herself to Christ. The biggest obstacle to its realization, however, was her dedication to her parents. It was not only because she was an only child but also because of their dependence on her owing to her father’s physical handicap. Her problem was how to be consecrated to Christ without leaving her parents alone. Providence intervened in November 1925. Victoria attended a lecture entitled The Pedagogical Character of St. Teresa and of her Works at a newly inaugurated Academia, a sort of residence for women studying in the Normal School. The members of the Institución Teresiana managed the foundation. The lecturer, Joséfa Grosso, was one of its members. Victoria left the lecture hall convinced that she had found what she was looking for. The Institución Teresiana, a pious association founded by Fr. Pedro Poveda, 2 Victoria, a woman of faith, lived her Teresian mission as a simple public school teacher. Education was to be her was of proclaiming the truth of God’s love. To speak of Christ during those days was risky, but she was not afraid. For her, Jesus Christ was “en primera fila,” over and above everything else. Just a few months after brilliantly passing the civil service examinations in 1927, Victoria received her first assignment to teach in the village of Cheles, in the province of Badajoz. Doña Victoria decided to accompany her daughter while Don José remained in Seville. Since the village was near the border of Portugal, Victoria found herself in an unpleasant situation: “They say that since this village was founded by Portuguese, it inhabitants speak Portuguese fluently. If that is so, then I am in a fix…” But that was not important for her: “As for me, I will conform myself with the will of God. It does not matter to me if I have to go to the ends of the world as long as it is for His glory and the salvation of all people.” VICTORIA DÍEZ BUSTOS DE MOLINA Victoria described Cheles: “It is an apathetic and indifferent town but it is not a bad one. No one has yet undertaken the formation of its girls; no one has guided them.” Within the year that she spent there, Victoria was able to bring Christ closer to her students and to the people as well. In July 1928, she was officially transferred to work in Hornachuelos, a small town in Cordoba. UNCELEBRATED TOWN Hornachuelos was an ancient and dormant town, uncelebrated by Andalucian poets and minstrels. It was a Spanish town like any other, save for some antique buildings. Its people were Catholics, at least by name. Only a few women regularly attended Mass. Complying with the new laws of Spain at that period, the local government had prohibited the teaching of catechism and ordered the removal of crucifixes from all classrooms. One would ask: why would such a brilliant teacher like her choose to continue living in such an apathetic town? It was not professional concern alone that moved her heart to remain in Hornachuelos. “I have asked the Lord to send me to a place where I would be loved less and known little by people. And after incessant prayer, I obtained from heaven what I had been asking for.” With such words, Victoria Díez explained her raison d’etre in Hornachuelos. In anti-clerical Spain, every effort was used to eradicate all traces of religion from the educational system. Victoria, who refused to go with the tide, became an absolute contradiction. She chose to partake in the poverty and ignorance of her students and their families. Instead of being a part of the babble of protesting rebellious voices and living a life of nonchalance, she chose to empathize with her adopted people. During the celebration of Book Day, the local authorities decided to distribute free reading materials to the students. The mayor entered Victoria’s class and while he spoke to the girls, she browsed over some of the reading materials he brought along. Horror was etched at her face when she saw the title of some of the pamphlets: “God Does Not Exist And Has Never Existed”, “Why Do the Bourgeoisies Believe In God”. When they were going to distribute the materials, Victoria firmly refused to participate. She did not want to be responsible of the degradation of her students. The mayor was surprised with her courage and ordered the books removed. EXCEPTIONAL EDUCATOR After her classes were dismissed, after the slow had been tutored, and after the classroom had been prepared for the morrow’s lessons, Victoria could be seen with the youth of Hornachuelos. She believed in the power of the youth to transform society and she did whatever she could to make this felt by them. With the permission of Fr. Antonio Molina Ariza, the parish priest, she organized the Student Catholic Action in that town. It was, for her, an effective way of bringing the Gospel into their hearts. She knew that organizing a youth association for them was not enough. She tried to develop a cordial yet respectable relationship with her students. “I liked her and she liked me, too,” commented one of them. “She was exceptional in school. In fact, we all respected her.” This respect was neither brought about by threats nor by intimidation. It was a reciprocal response of her students to the respect she had shown them as persons. She trusted her students and placed her hope in them. But her work did not end there. Most of her students were poor. Victoria wanted to alleviate their sufferings, even just a little. One witness testified: “Señora Gamero Cívico, one of the better-off residents of the town, gave her pieces of linen cloth and fabrics for the girls in school and, out of 3 SAINTS JOURNEYING WITH US these, she would make overcoats for the girls.” She fed them, gave them money for the medicine of their mothers, provided their shoes… These were some of the ways of showing her love for her students. EVEN IF MY BLOOD RUNS COLD Victoria felt that Hornachuelos was challenging her to a greater self-giving. Thus, she made a deal with Christ: “Ask me the price, ask whatever you want from me in exchange for the salvation of this town… even if my blood turns cold.” She dared to make a covenant, and she never faltered or vacillated. Subsequently, when Cordoba was entangled in the civil war, she was sure that her time had come. The townspeople appreciated her presence in Hornachuelos, even by those who did not share her beliefs. Among them was Arturo, who was a teacher of a neighboring school for boys. He was a Socialist, but he was a very good friend of Victoria: “She was an admirable woman even if our ideas are very different.” There were also those who saw her work as a contradiction to the animosity they were sowing against religion. She was, for them, a nuisance, an obstacle to their plans, one who had to be weeded out: “We have to kill her, otherwise, she will lead the people away from our goal.” IN A MAKESHIFT PRISON The first gunshots of the chaotic civil war were fired in Hornachuelos on July 20. Fr. Molina hastily emptied the tabernacle and, with Victoria and his sisters, consumed some of the species and transported the remaining to his house. On that same day, members of the revolutionary committee apprehended him. Wagging tongues speculated his lot and of the other detainees. Victoria, whom he considered as his “coadjutor”, would carry on the work he abruptly left behind. The parish church was later ransacked and burned. Those were days of fear and anxiety. 4 It was eight in the evening of August 11. Victoria was giving a class in religion to a group of women. Two armed men brusquely presented themselves and requested that Victoria join them. Her declarations were needed. Calmly she bade farewell to her mother. The house of Francisco Gamero Civico had been transformed into a temporary detention center. She was the only woman among those who were detained. Some of these men, in fact, had been there for twenty-two days. Among them was Fr. Molina. Victoria managed to slip a small note for her mother through her young students who were peering at her cell. “Do not be afraid, Mother. I will be here until they get my declaration. Right now, I am in the house of Don Paco.” Doña Victoria lost no time and rushed to her daughter’s side. Except for an embrace, a kiss and a profound gaze, no words were exchanged between them. They somehow felt the same presentiment. After she left the makeshift prison, Doña Victoria gave way to her feelings and wept. AND A WOMAN LED THEM At about two in the early hours of the following day, Victoria and her companions were awakened. “The Fascists are coming. We are going to transfer you all.” It was a deception. The eighteen captives were forced to walk to their “new prison”. It was a walk that would bewilder any one… a march of twelve kilometers. They were lonely figures silhouetted by the ominous darkness, carefully watched by forty milicianos with rifles at hand. Fatigue and hunger exacerbated the suffering of the ill-fated detainees. One of them fell along the way. The milicianos forced another captive to carry him throughout the walk. No one must be left behind. Victoria kept her composure. Ironically, it was she who encouraged and inspired the men to go on: “Take heart! I see the heavens VICTORIA DÍEZ BUSTOS DE MOLINA open. The prize awaits us! Let us go! Forward!” Some of the men cried uninhibitedly. Victoria consoled and encouraged them throughout their terrible Via Crucis. Finally, after three hours, they reached their destination. The abandoned mine of El Rincon was clearly not a penitentiary. A pit of 180 meters deep awaited the prisoners. Above it was a big stone. A mock tribunal was established; the judgment was quick and unanimous – death. FINAL TESTIMONY One by one, the men were positioned on the stone and shot, falling perfectly into the pit below. Victoria watched these men killed one after another- her parish priest, the relatives of her students, friends she made after nine years of faithful service in Hornachuelos. Surely, she watched with a stout heart. The teacher was summoned. Gathered around her in a semi-circle, they tried to coax her: “Just say ‘¡Viva la Republica!’ or ‘¡Viva el Comunismo!’ and we will save your life.” “Give me a minute to think,” she replied. Victoria knelt on the stone and opened her arms in the form of a cross. One of her fists was closed. The milicianos thought that they have won her over. Not so. With her eyes raised to the skies, Victoria spoke: “No, no and no! I say what I feel: ¡Viva Cristo Rey! Viva mi Madre!” A volley of gunfire broke the stillness of the night. Down fell the body of the valiant teacher to the pit that hungrily awaited her. The brutal deed was done. The assassins left. Some people testified that they heard the moans of some of those in the pit hours after they were shot, but no one dared approach them for fear of their own lives. Soon, only an eerie silence deafeningly pervaded the spot. The young girls of Hornachuelos had lost their teacher but not her shining example. Her most important lesson was not lectured though in their classroom; it was given in the lonely nocturnal landscape of El Rincon. The testimony of Victoria would live on. ***** THE DECREE ON THE MARTYRDOM OF VICTORIA DÍEZ BUSTOS DE MOLINA WAS PROMULGATED ON 6 JULY 1993. SHE WAS BEATIFIED ON 1 OCTOBER 1993. BIBLIOGRAPHY Cimino, Maria. Un Dono Totale: Vita di Vittoria Diez. Milan: Editrice Ancora, 1966. Fernández Aguinaco, Carmen. Victoria Díez: Memoria de una Maestra. Madrid: Narcea, 1993. Grosso Sánchez, Ma. Josefa. Veo el Cielo Abierto. Madrid: Institución Teresiana, 1957 COPYRIGHT 2002 © THE HAGIOGRAPHY CIRCLE. 5