- Ninguna Categoria

Problemas generales de filosofía de la ciencia. Núcleo: Cursos de o

Anuncio

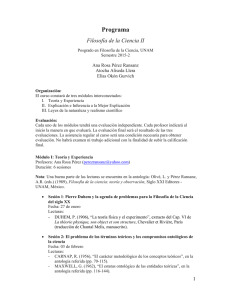

SECRETARÍA DE POSGRADO MAESTRIA EN FILOSOFÍA Asignatura: Problemas generales de filosofía de la ciencia. Núcleo: Cursos de orientación Cantidad de horas: 36. Período lectivo: Primer trimestre de 2014. Profesores: Dr. José A. Díez Calzada y Dra. María de las Mercedes O’Lery. PRESENTACIÓN El propósito general de este curso es proporcionar al alumnado conocimientos básicos de las principales problemáticas de la filosofía general de la ciencia, profundizando en temas tales como la representación y los modelos, los aspectos propios de los enfoques semanticistas de las teorías científicas, la polémica del realismo científico, los enfoques actuales sobre la explicación científica, el problema de la contrastación de las teorías científicas, las relaciones interteóricas e interdisciplinares, los modelos de cambio científico y la idealización y aproximación. OBJETIVOS Se espera que el cursado de la asignatura contribuya a que el alumnado satisfaga las siguientes expectativas de logro: 1) comprenda la complejidad e importancia de los problemas generales de filosofía de la ciencia desarrollados en el curso; 2) adquiera un dominio razonable de la bibliografía básica de cada una de las problemáticas aquí tratadas, elaborando, a su vez, un juicio crítico acerca de las distintas posturas planteadas en cada una de estas; 3) comprenda la importancia de la problemática de la representación y los modelos en la filosofía de la ciencia; 4) advierta la relevancia de la polémica del realismo científico, así como los argumentos principales de las distintas posturas; 5) ahonde en el problema de la explicación científica y comprehenda y evalúe los distintos enfoques actuales; 1 6) comprenda la complejidad de la problemática de la contrastación de las teorías científicas, y tenga un dominio razonable de las distintas posiciones al respecto; 7) perciba la importancia del tratamiento en filosofía de las ciencias de las relaciones interteóricas e interdisciplinares; 8) logre un nivel de análisis de los distintos modelos de cambio científico; 9) comprenda la importancia y complejidad en la caracterización de las nociones de idealización y aproximación. CONTENIDOS TEMÁTICOS UNIDAD 1: LA CONTRASTACIÓN DE HIPÓTESIS Y TEORÍAS Elementos, condiciones y resultado de la contrastación. La confirmación y sus problemas: lógicas inductivas, bayesianismos, pragmatismos. La refutación y sus problemas: falsacionismo ingenuo y falscionismo sofisticado. Bibliografía obligatoria Carnap, R., (1960) “The aim of Inductive Logic”, 1960. En Nagel, E., Suppes, P. y A. Tarsky (eds.), Proceedings of the 1960 International Congress for Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science, vol. 1, Stanford U. P., Standford, pp. 303-318, 1962. Lakatos, I. ([1974] 1975) “La falsación y la metodología de los programas de investigación científica”. En Lakatos, I. ([1978] 1989), La metodología de los programas de investigación, Alianza Editorial, Cap. 1, sección 1, pp. 17-20, Sección 2, pp.20-66, sección 3, a y b, pp. 66-72. Popper, Karl ([1963] 1983), Conjeturas y refutaciones, 2da. Edición, Barcelona, Paidós, cap. 1, 10 y 11. UNIDAD 2: REPRESENTACIÓN Y MODELOS Enunciados y modelos. Tipos de modelos (estructuras, espacios de estados, mapas). Función de los modelos. Modelos y la naturaleza de la representación. Representación e idealización. Bibliografía obligatoria Frigg, R., y S. Hartmann, (2011), “Models in Science”, Stanford Enc. of Phil., http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/models-science/ UNIDAD 3: ENFOQUES SEMANTICISTAS DE LAS TEORÍAS CIENTÍFICAS Concepciones axiomática e historicista. Teorías y modelos. Teorías empíricas como conjuntos de modelos. La familia semanticista: Suppes, Van Fraassen, Suppe, Giere, estructuralismo. La concepción estructuralista. Bibliografía obligatoria Giere, R. (1988), Explaining science. A cognitive approach, Chicago: Chicago University Press., cap. 3. 2 Moulines, C. U. (1982), Exploraciones metacientíficas, Madrid, Alianza, cap. 2 , secciones 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 y 2,4 (pp. 63-116) y sección 2.8 (pp. 191-203). van Fraassen, B. C. ([1980] 1996), La imagen científica, México, Paidós, cap. 3. UNIDAD 4: LA EXPLICACIÓN CIENTÍFICA Hempel, la explicación como inferencia y sus problemas. Pragmatismo, monismo y pluralismo explicativo. Causalismo, manipulativismo y mecanicismo. Unificacionismo o inferencialismo sistémico. Subsunción teórica ampliativa. Bibliografía obligatoria Díez, J. (2012), “La explicación científica: causalidad, unificación y subsunción teórica”. En Peris Viñé, L. M. (ed.), Filosofía de la ciencia en iberoamérica: metateoría estructural, Madrid, Tecnos, pp. 517-562. Hempel, C. ([1965] 1979), La explicación científica. Estudios sobre la filosofía de la ciencia, Buenos Aires, Piadós, cap. XII. Kitcher, P., (2001), El avance de la ciencia, México, UNAM, cap. 3. Salmon, W. (2002), “Explicación causal frente a no causal”. En González, W. (ed.), Diversidad de la explicación científica, Barcelona: Ariel, pp. 97-116. UNIDAD 5: RELACIONES INTERTEÓRICAS E INTERDISCIPLINARES Relaciones interteóricas. Reducción. Equivalencia. Teorización. Reduccionismo y fisicalismo. Bibliografía obligatoria Díez, J. y C. U. Moulines (1998), Fundamentos de Filosofía de la Ciencia, Barcelona, Ariel, cap. 11. Nagel, E. ([1961] 1991), La estructura de la ciencia, Barcelona, Paidós, cap. 11. “Phisicalism”, Stanford Enc. of Phil., http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/physicalism/ UNIDAD 6: CAMBIO CIENTÍFICO Tipos de cambio. Cristalización. Cambio intrateórico. Cambio interteórico: sustitución, suplantación e incorporación. El progreso y la racionalidad científicos. Bibliografía obligatoria Díez, J. y C. U. Moulines (1998), Fundamentos de Filosofía de la Ciencia, Barcelona, Ariel, cap. 13. Kuhn, T. S. ([1981] 1989), ¿Qué son las revoluciones científicas? y otros ensayos, Barcelona, Paidós, caps. 1 y 2. Moulines, C. U. (2011), “Cuatro tipos de desarrollo teórico en las ciencias empíricas”, Metatheoria – Revista de Filosofía e Historia de la Ciencia 1(2): 11-27. UNIDAD 7: REALISMO CIENTÍFICO Realismo y realismo científico. Realismo sobre inobservables y realismo sobre leyes/propiedades. El debate sobre el realismo de inobservables: realismo, antirealismo, 3 realismo selectivo. El debate sobre el realismo de leyes/propiedades: Humeanismo, nominalismo, realismo. Bibliografía obligatoria Díez, J. y C. U. Moulines (1998), Fundamentos de Filosofía de la Ciencia, Barcelona, Ariel, cap. 5. Frigg, R. and I. Votsis, (2011), “Everything you always wanted to know about structural realism but were afraid to ask”, European Journal Philosophy of Science 1:227–276. Psillos, S. (2011), “Realism with Humean face”, in French, S. and J. Saatsi (eds.), Continuum Companion to the Philosophy of Science, pp. 75-95. vanFraassen, B. (1985), “¿Qué son las leyes de la naturaleza?”, Dianoia 31: 211-262. Worrall, J. (1989), “Structural Realism: The Best of Both Worlds?”, Dialéctica 43(1-2): 99-124. Bibliografía recomendada: Achinstein, P. (1983), The Nature of Explanation, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Adams, E. (1959), “The Foundations of Rigid Boyd Mechanics and the Derivation of Its Laws from Those of Particle Mechanics”, en Henkin, Suppes y Traski (1959), pp. 250-265. Armstrong, D. (1983), What is a law of nature, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Balzer, W., Sneed, J. y C.U. Moulines (2000), Structuralist knowledge representation.Knowledge Representation.Paradigmatic examples, Masterdam-Atlanta, Rodopi. Balzer, W. y C.U. Moulines (eds.) (1996), Structuralist Theory of Science.Focal Issues, New Results, New York, Walter de Gruyter. Bechtel, W., y A. Abrahamsen (2005), “Explanation: A Mechanist Alternative”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 36: 421-441. Black, M. (1962), Models and Metaphors, Ithaca, Cornell University Press. Boyd, R. N. (1983), “On the Current Status of the Issue of Scientific realism”, Erkenntnis 19: 45– 90. Bromberger, S. (1962), "An Approach to Explanation", en Butler, R., Analytical Philosophy, Second Series, Basil Blackwell, Oxford, pp. 72-105. Brown, James R. (1985), “Explaining the Success of Science”, Ratio XXVII: 49-66. Callender, C. y J. Cohen (2006), “There is no Special Problem of Scientific Representation”, Theoria55: 67–85. Carnap, R., (1950), “Empiricism, Semantics and Ontology”, Revue Intérnationale de Philosophie 4: 20–40. Carrier, M. (1991), “What is wrong with the Miracle Argument?”,Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 22(1): 23-36. Cartwright, N. (1999a), The Dappled World: A Study of the Boundaries of Science, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Cartwright, N. y M. Jones (eds.) (1999b), Idealizations in Physics, Amsterdam, Rodopi. Cartwright, N. (2010), “Models: Parables and Fables?”, en Frigg, R. y M. Hunter (eds.), Beyond Mimesis and Convention, Springer, London, pp. 19-32. Chakravarty, A. (1988), “Semirealism”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 29(3): 391408. Chakravartty, A. (2008), “What You Don't Know Can't Hurt You: Realism and the Unconceived”, Philosophical Studies 137: 149–158. Chakravarty, A. (2010), “Informational versus functional theories of scientific representation”, Synthese172(2): 197-213. Contesa, G. (2007), “Scientific Representation, Interpretation, and Surrogative Reasoning”, Philosophy of Science 74: 48-68. Da Costa, N. (2000), “Models, Theories and Structures: Thirty Years On”, Philosophy of Science 67: S126-127. 4 Da Costa, N. y S. French (2003), Science and Partial Truth: A Unitary Approach to Models and Scientific Reasoning, New York, Oxford University Press. Dalla Chiara, M. y G. Toraldo di Francia (1973). “A Logical Analysis of Physical Theories”, Rivista di NuovoCimento 2(3): 1-20. Dalla Chiara, M. y G. Toraldo di Francia (1976), “The Logical Dividing Line between Deterministic and Indeterministic Theories”, StudiaLogica 35: 1-5. Devitt, M. (1991), Realism and Truth, Princeton: Princeton University Press (second edition, first edition: 1984). Díez, J. (2007), “Popper–Kuhn controversy about the rationality of normal science”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 38: 543-554. Díez, J., (2011), “On Popper’s strong inductivism (or strongly inconsistent anti-inductivism), Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 42: 105-116. Díez, J. (2013), “Scientific w-Explanation as Ampliative, Specialized Embedding: A NeoHempelian Account”, Erkenntnis: 1-31 (forthcoming) Dowe, P. (1995), “Causality and Conserved Quantities: A Reply to Salmon”, Philosophy of Science 62: 321-333. Earman, J. (1992), Bayes or Bust? A Critical Examination of Bayesian Confirmation Theory, Cambridge, MA., MIT Press. Fine, A., (1986), “Unnatural Attitudes: Realist and Antirealist Attachments to science”, Mind 95: 149–177. Fine, A. (1984), “The Natural Ontological Attitude”, en Leplin, J., Scientific Realism, California, University of California Press, pp. 83-107. Fitelson, B. (1999), “The Plurality of Bayesian Measures of Confirmation and the Problem of Measure Sensitivity”, Philosophy of Science 66 (Proceedings Supplement): S362-378. Frebch, S. (2003), “A Model-Theoretic Account of Representation”, Philosophy of Science 70: 1472-1483. Friedman, M. (1974), “Explanation and Scientific Understanding”, The Journal of Philosophy 71: 5-19. Frigg, R. (2006), “Scientific Representation and the Semantic View of Theories”, Theoria 55: 4965. Frigg, R. (2010), “Fiction and Scientific Representation”, Frigg, R. and M. Hunter (eds), pp. 97138. Giere, R. (1988), Explaining science. A cognitive approach, Chicago: Chicago University Press., cap. 3. Giere, R. (2004), “How Models are Used to Represent Physical reality”, Philosophy of Science 71: 742-752. Giere, R. (2006), Scientific Perspectivism, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press. Giere, R. (2008), “An Agent-Based Conception of Models and Scientific Representation”, Synthese 172(2): 269-281. Godfrey-Smith, P. (2009), “Models and Fictions in Science”, Philosophical Studies 143: 101-116. Hacking, I. (1985), “Do We See Through a Microscope?”, en Churchland& Hooker (eds.), Images of Science: Essays on Realism and Empiricism, (with a reply from Bas C. van Fraassen), Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Hardin, C. y A. Rosenberg (1982), “In defense of Convergent Realism”, Philosophy of Science 49: 604-615. Harré, R. (1994), “Three varieties of realism”, en Derksen, A., (ed.), The Scientific Realism of Rom Harré, Tilburg University Press, pp. 5-22. Hempel, C. (1962) “Deductive-Nomological versus Statistical Explanation", en Feigl y Maxwell (eds.), Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol. III, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, pp. 98-170. Hempel, C. (1983), “Kuhn and Salmon on Rationality and Theory Choice”, Journal of Philosophy 80(10): 570-572. 5 Hempel, C. y P. Oppenheim (1948), “Studies in the Logic of Explanation”, Philosophy of Science 15: 567-579. Henkin, L., Suppes, P. y A. Tarski (eds.) (1959), The Axiomatic Method, Amsterdam, North Holland. Hesse, M. (1963), Models and Analogies in Science, London, Sheed and Ward. Howson, C. y P. Urbach (1989), Scientific Reasoning.The Bayesian Approach, La Salle, Open Court. Hughes, R. (1993), “Theoretical Explanation”, Midwest Studies in Philosophy 18(1):132-153. Hughes, R. (1997), “Models and Representation”, Philosophy of Science 64: S325-336. Humphreys, P. (1989), “Scientific Explanation: The Causes, Some of the Causes, and Nothing but the Causes”, en Kitcher, P. y W. Salmon (eds.), Scientific Explanation, Minneapolis, U. Minnesota P., pp. 283-306. Ibarra, A. y T. Mormann (1997), “Theories as Representations”, en Ibarra-Mormann (eds.), Representations of Scientific Rationality, Poznan Studies vol. 61, Rodopi, Amsterdam. Jones, M. y N. Cartwright (eds.) (2005), Idealization XII: Correcting the Model. Idealization and Abstarction in the Sciences, Amsterdam, Rodopi. Jones, R. (1991), “Realism about what?”,Philosophy of Science 58: 185-202. Kitcher, P. (1978), “Theories, Theorists and Theoretical Change”, Philosophical Review 87: 519547. Kitcher, P. (1981), “Explanatory Unification”, Philosophy of Science 48: 507-531. Kitcher, P. (1989), “Explanatory Unification and the Causal Structure of the World”, en Kitcher, P. y W. Salmon (eds.), Scientific Explanation, Minneapolis, U. Minnesota P., pp. 410-505. Kitcher, P. (2001), “Real Realism: The Galilean Strategy”, The Philosophical Review 111: 151197. Kitcher, P. y W. Salmon (1987), “Van Fraassen on Explanation”, The Journal of Philosophy 84: 315-330. Kuhn, T. (1983), “Rationality and Theory Choice”, The Journal of Philosophy 80(10): 563-570. Kuhn, T. (1970a), “Reflections on my Critics”, en Lakatos, I. y R. Musgrave (eds.), pp. 231-278. Kuhn, T. (1970b), Second Thoughts on Paradigms, Urbana, U. Illinois P. Kuhn, T. (1970c), “Logic of Discovery or Psychology of Research?”, en Lakatos, I. y R. Musgrave (eds.), pp. 1-23. Kuhn, T. (1975), “Theory Change as Structure Change”, Erkenntnis 10: 179-200. Kuhn, T. ([1962] 1995), La estructura de las revoluciones científicas, 2da. ed., México, Fondo de Cultura Económica. Ladyman, J. (1998), “What is Structural Realism?”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 29: 409–424. Lakatos, I. (1968), “Changes in the Problem of Inductive Logic”, en Lakatos (ed), The Problem of Inductive Logic, Amsterdam, North Holland, pp. 315-417. Lakatos, I. y A. Musgrave ([1974] 1975), Crítica y desarrollo del conocimiento. Actas del Coloquio Internacional de Filosofía de la Ciencia celebrado en Londres, en 1965, Barcelona, Grijalbo. Laudan, L. ([1990] 1993), La ciencia y el relativismo, Madrid, Alianza. Leplin, J., (1981), “Truth and Scientific Progress”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 12: 269–292. Leplin, J. (1997), A Novel Defense of Scientific Realism, Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lewis, P. (2001), “Why the pessimistic induction is a fallacy”, Synthese 129: 371-380. Machamer, P., Darden, L. y C. Craver (2000), “Thinking About Mechanisms”, Philosophy of Science 67: 1-25. Magnus, P. y C. Callender (2004), “Realist Ennui and the Base Rate Fallacy”, Philosophy of Science 71: 320-338. Matheson, C. (1998), “Why the no-miracles argument fails”, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 12: 263-279. 6 Maxwell, G. (1962), “On the Ontological Status of Theoretical Entities”, en Feigl, H. y G. Maxwell (eds.), Scientific Explanation, Space, and Time, Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science, Volume III, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. McMullin, E. (1984), “A Case for Scientific Realism”, en Leplin (1984), pp. 8-40. Moulines, C. U. (2005), “Models of Data, Theoretical Models, and Ontology”, en Hoffmann, M. et al. (eds.), Activity and Sign, Springer, USA, pp. 325-333. Moulines, C. (1991), Pluralidad y recursión. Estudios epistemológicos, Madrid, Alianza. Mundy, B. (1986), “On the general Theory of Meaningful Representation”, Synthese 67: 391437. Papineau, D. (2010), “Realism, Ramsey Sentences and the Pessimistic Meta-Induction”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 41: 375–385. Pollock, J. (1990), Nomic Probability and the Justification of Induction, New York, Oxford U.P. Popper, K. (1970), “Normal Science and its Dangers”, en Lakatos, I. y A. Musgrave (eds.), pp. 51-58. Przelecki, M. (1969), The Logic of Empirical Theories, Londres, Routledge&Kegan Paul. Psillos, S. (1996), “Scientific Realism and the ‘Pessimistic Induction”’, Philosophy of Science 63 (Proceedings): s306-s314. Psillos, S. (1999), Scientific Realism. How science tracks truth, London-New York: Routledge. Psillos, S. (2000), “Empiricism vs. Scientific Realism: Belief in Truth Matters”, International Studies in the Philosophy of Science 14: 57-75. Putnam, H. (1974), “On the ‘corroboration’ of theories”, en Schilpp, P. (ed.), The Putnam, H. (1984), “What is Realism?”, en Leplin (1984), pp. 140-153. Railton, P. (1978), “A Deductive-Nomological Model for Probabilistic explanation”, Philosophy of Science 45: 206-226. Rivadulla, A. (1991), Probabilidad e Inferencia Científica, Barcelona, Anthropos. Ruben, D. (1991), Explaining Explanation, New York, Roudledge and Kegan Paul. Salmon, W. (1967), The Foundations of Scientific Inference, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press. Salmon, W. (1971), Statistical Explanation & Statistical Relevance, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press. Salmon, W. (1981), “Causality: Production and Propagation”, in Asquith, P. y R. Giere (eds.), PSA 1980, Philosophy of Science Association, East Lansing MI, pp. 49-69. Salmon, W. (2002), “La estructura de la explicación causal”. En González, W. (ed.), Diversidad de la explicación científica, Barcelona, Ariel, pp. 141-160. Shanks, N. (ed.) (1998), Idealization IX: Idealization in Contemporary Physics, Amsterdam, Rodopi. Sneed, J. (1983), “Structuralism and Scientific Realism”, Erkenntnis 9: 345-360. Sober, E. (2002), “Bayesianism—Its Scope and Limits”, en Swinburne, R. (ed.), Bayes's Theorem, Oxford, Oxford University Press, pp. 21-38. Stanford, P. (2003a), “Pyrrhic Victories for Scientific Realism”, Journal of Philosophy 100: 553– 572. Stanford, P. (2003b), “No Refuge for Realism: Selective Confirmation and the History of Science”, Philosophy of Science 70: 913-925. Stegmüller, W. (1970), Theorie und Erfahrung, Heidelberg, Springer. Strevens, M. (2004), “Bayesian Confirmation Theory: Inductive Logic, or Mere Inductive Framework?”,Synthese141: 365-379. Suárez, M. (2004) “An Inferential Conception of Scientific Representation”, Philosophy of Science, 71: 767-779. Suárez, M. (ed.) (2009) Fictions in Science: Philosophical Essays on Modelling and Suárez, M. (2003), “Scientific Representation: Against Similarity and Isomorphism”, Intern. Stud. inPhil.of Sc. 17: 225-244. 7 Suárez, M. y N. Cartwright (2008), “Theories: Tools versus Models”, Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics 39: 62-81. Suppe, F. (1972), “What’s wrong with the Received-View on the Structure of Scientific Theories?”,Philosophy of Science 39: 1-19. Suppe, F. (ed.) (1974), The Structure of Scientific Theories, Urbana, University of Illinois Press. Suppes, P. (1954), “Some Remarks on Problems and Methods in the Philosophy of Science”, Philosophy of Science 21: 242-248. Suppes, P. (1957), Introduction to Logic, New York: Van Nostrand. Suppes, P. (1960), “Una comparación del significado y los usos de los modelos en las matemáticas y las ciencias empíricas”, en Estudios de filosofía y metodología de la ciencia, Madrid, Alianza, 1988, pp. 109-123. Suppes, P. (1967), “What is a Scientific Theory?”, en Morgenbesser, S. (ed.) Philosophy of Science Today, New York: Basic Books, pp. 55-67. Suppes, P. (1989), “Representation Theory and the Analysis of Structure”, PhilosophiaNaturalis 25: 254-268. Suppes, P. (2002), Representation and Invariance of Scientific Structures, Stanford, CSLI. Swoyer, C. (1991), “Structural Representation and Surrogative Reasoning”, Synthese 87: 449508. Tichý, P. (1974), “On Popper's definitions of verisimilitude”, The British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 25: 155-160. Toon, A. (2010), “Models as Make Believe”, Frigg, R. y M. Hunter (eds), pp. 71-96. vanFraassen, B. (1970), “On the extension o Beth's Semantics of Physical Theories”, Philosophy of Science 37: 325-339. vanFraassen, B. (1984), “To save the phenomena”, en Leplin (1984), pp. 250-260. vanFraassen, B. (1989), Laws and Symetry, Oxford: Clarendon Press. vanFraassen, B. (1997), La imagen científica, Barcelona, Paidós. vanFraassen, B. (2004), “Science as Representation: Flouting the Criteria”, Philosophy of Science 71: 794-803. vanFraassen, B. (2009), Scientific Representation, Oxford, OUP. Weisberg, M. (2007), “Who is a Modeller?”,British Journal for the Philosophy of Science 58: 207-233. Worrall, J. (1994), “How to Remain (Reasonably) Optimistic: Scientific Realism and the ‘Luminiferous Ether’”, en Hull, D., Forbes, M. y R. M. Burian (eds.) PSA 1994, Vol. 1, East Lansing, MI: Philosophy of Science Association. 8

Anuncio

Documentos relacionados

Descargar

Anuncio

Añadir este documento a la recogida (s)

Puede agregar este documento a su colección de estudio (s)

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizadosAñadir a este documento guardado

Puede agregar este documento a su lista guardada

Iniciar sesión Disponible sólo para usuarios autorizados