From Shadow to Formal Economy - European Parliament

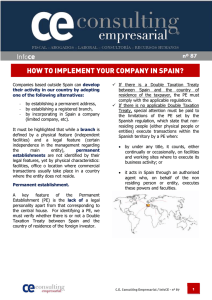

Anuncio