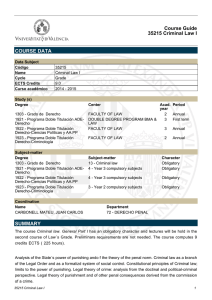

- Ninguna Categoria

English

Anuncio