China and Latin America

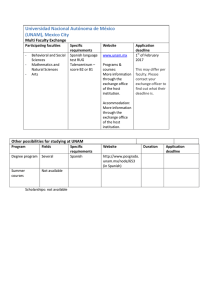

Anuncio