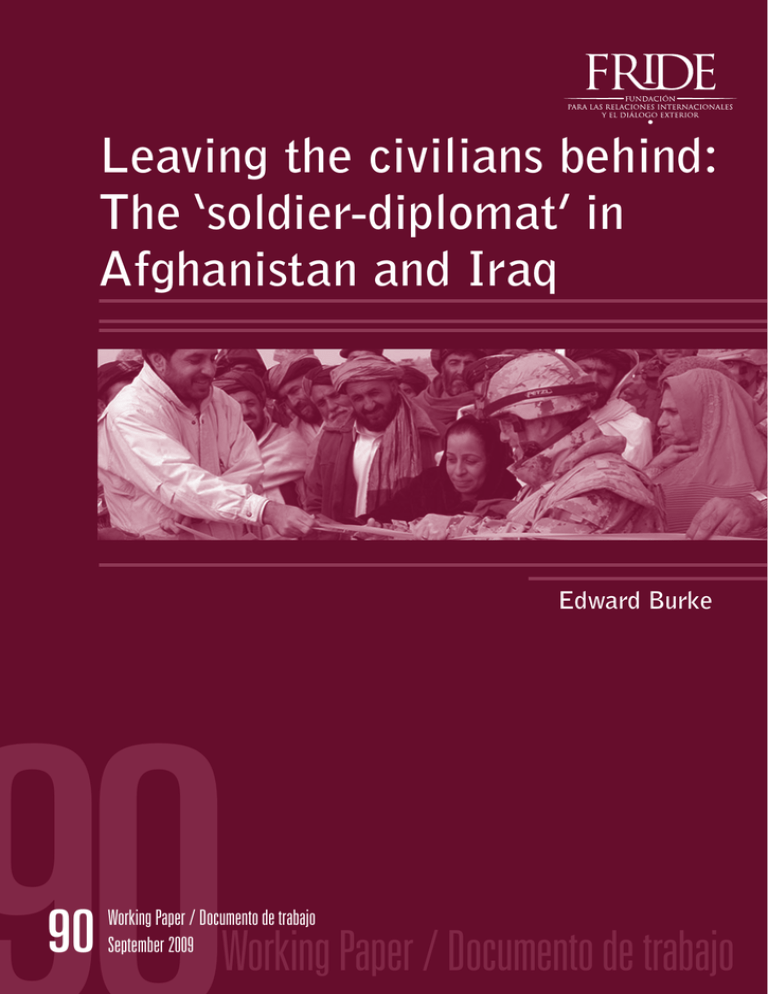

Leaving the civilians behind: The `soldier-diplomat`in

Anuncio