Twenty-One Countries, Millions of Native Speakers, and One

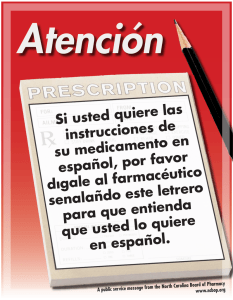

Anuncio