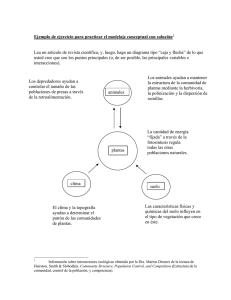

Crecimiento y reproducción de Anthurium schlechtendalii

Anuncio